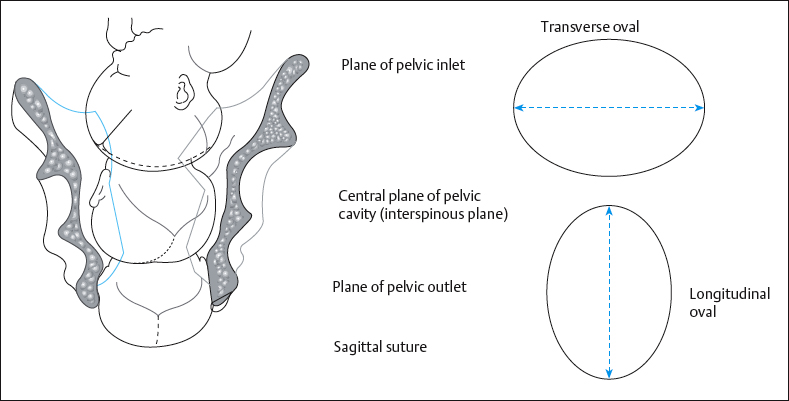

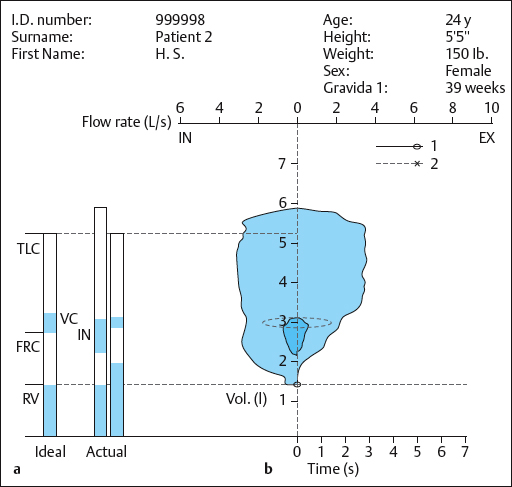

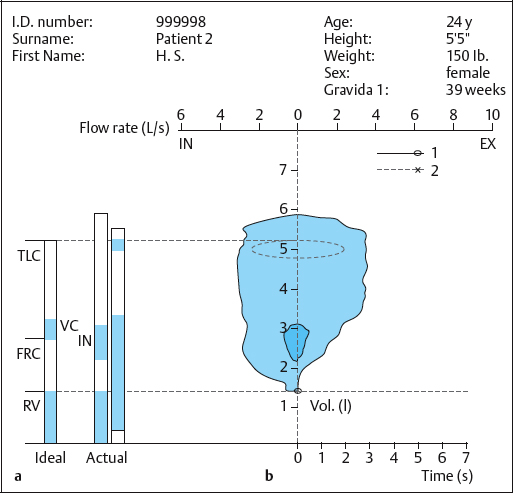

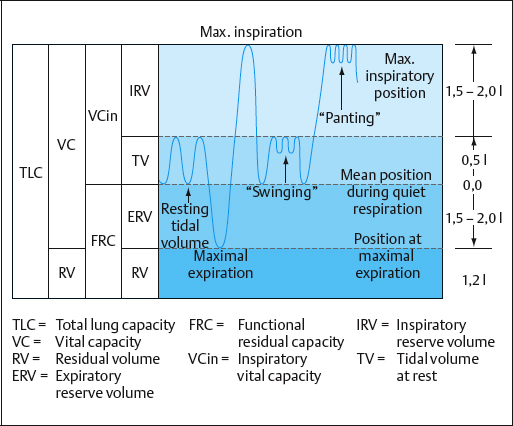

4 Therapy for Women The entirety of every aspect of prenatal preparation advocated here–including “swinging” and “sliding” to assist sliding the baby out–can be termed the Menne–Heller method. This method, which develops prenatal preparation up to a certain point, could be called “psychosomatic” or “holistic.” I would like to explain briefly why I have not used this term. My forerunner in this field was the physiotherapy educator Ruth Menne (1913–1986). She was the first to include the unborn child and the mother–child bond in the concept of prenatal preparation. She wanted to guide her pregnant clients to explore themselves and to be responsible for their own preparation by using her psychophysical approach. However, she never put her ideas about prenatal preparation down in writing. In 1981, Ruth Menne passed her work on to me. In the years that followed, I continued to develop this methodological approach and I subsequently placed the work on a reliable and well-substantiated basis. The concept of “swinging” is now used in many birthing centers in Germany, parts of Switzerland, and Austria. The work focuses on prenatal preparation that is based on natural principles and is behaviorally oriented. It emphasizes functionality, especially in the woman’s self-directed activity during labor, and it is capable of being formulated in a structured way. This applies in particular to “body work” and the “work of breathing.” In the educational part of this chapter I intend to develop an understanding of the effect of such actions, including the actions emphasized here– namely, “sliding” and “swinging.” This part includes specialized instruction in obstetrics in order to demonstrate the connections–which can be termed “informative prenatal preparation.” I spent a long time trying to think of a term for this approach that would sum up the entirety of every aspect of this type of prenatal preparation. Finally, I decided to name the approach after the two people who originated it: with Ruth Menne’s name, in gratitude for her pioneering work, which played a decisive role in my own thinking and in the eventual development of my own current work. Combining her name with my own, I called this approach the Menne–Heller method [Heller 1998]. This section addresses a part of the method that is designed to take care of the pelvic floor during labor. Childbirth often triggers a pelvic floor imbalance or dysfunction, especially if the pelvic floor has suffered traumatic injury during delivery and timely and expert treatment was not provided in the puerperium. Any impairment of pelvic floor function can lead to poor health in the later years of a woman’s life. There is unanimous agreement that injuries to structures, especially third-degree and fourth-degree perineal tears and forceps extraction, should be regarded as presenting an increased risk for later urethral and anal pelvic floor dysfunction, including sexual problems. Similarly, uterine or vaginal prolapse can be a sequela of vaginal delivery. Even a cesarean section does not ensure that pelvic floor imbalances and dysfunctions can be avoided [Heller 2002]. The natural postpartum capacity for self-healing (e.g., regeneration of an injured muscle, which is capable of building identical new tissue) can only come into play when the muscular, fascial, connective-tissue, nervous and bony structures of the birth canal that are disturbed by the hormonal changes of labor have undergone only moderate– that is, non-traumatic–structural changes. Management of labor is therefore extremely important. Many publications have established that the upright or semi-upright position for labor is preferable to the horizontal, supine (lithotomy) position, both for the well-being of the mother and her pelvic floor as well as for the infant’s well-being [Caldeyro-Barcia 1979a, 1979b, Kirchhoff 1982, Huch 1983, Huch and Huch 1984, McKay 1984, Paciornik 1992, Parnell et al. 1993, Kuntner 1994, Kirchhoff 1995, Kreuter 1995, Kuntner 1995, Mendez-Bauer et al. 1995, Goschen 1996, Heller 1998, 2002]. These positions are easier on both the mother and the child, and are functionally more correct. As early as 1985, the World Health Organization issued recommendations at a conference in Fortaleza, Brazil, favoring the use of upright or semi-upright positions during labor [World Health Organization 1985]. These recommendations are rarely followed, and women still deliver in the lithotomy position. They are instructed to hold their breath for a prolonged period and to push with the resulting Valsalva pressure. It is not uncommon for the birth attendant (nurse, midwife, physician, or partner) to use the Kristeller maneuver, in which downward pressure is applied to the uterine fundus from outside the abdomen synchronously with a contraction. This chapter will contrast the unfavorable effect on the maternal pelvic floor of giving such directions during the expulsion phase of labor, with the advantages for pelvic floor prophylaxis provided by: Apart from all of the other psychophysical advantages, this approach to labor also prevents damage to the pelvic floor. From the very beginning of labor, in the first stage, many stimuli induce changes in the woman’s breathing pattern. Thus, a sudden initiation of labor before the calculated date of term–e. g., by bleeding, breaking of the waters, or contractions–will change the breathing pattern. Moreover, if labor begins at term, there are still a number of situations that will change resting respiration. Anxiety, nervous restlessness, expectation of the pain and physical exertion of contractions, and often worry about not reaching the hospital in time can dispel the composure the woman originally intended to show at the start of labor. There are also a number of stimuli at the hospital that can change the breathing pattern–e.g., vaginal examinations, especially if they are painful, as well as the examiner’s cold hands, instruments, and injections. In addition there are the uterine contractions, occurring at ever shorter intervals as they work to fully open the cervix. The pregnant woman’s respiratory response depends on the strength and duration of the contractions (an effective contraction lasts about 60 s), as well as on the total length of labor and the circumstances surrounding it. It certainly also depends on the woman’s ability to surrender to events and deal with pain. Intense pain always intensifies respiration. As a result, many women in labor–especially if they are anxious, and those who are not familiar with aids to respiration–will shorten the interval between breaths. One rapid breath follows the next. Because the inspired air is drawn through the narrowed nasal turbinates, the rapid respiration with emphasized inspiration becomes audible. This rapid respiration and its effect on the infant was noted in 1980 by the gynecologist Saling, who wrote that one should “Make sure that respiratory frequency remains at only six to eight breaths per minute, to ensure that excessively rapid respiration does not become automatic as a result of being practiced during prenatal training” [Saling 1980]. To achieve a low respiratory frequency during prenatal work, the Menne–Heller prenatal training course requires that breathing instructions should not include counting [Heller 1998]. Initially, the woman must concentrate on becoming aware and conscious of spontaneous resting respiration, without making any voluntary changes. Later, costoabdominal respiratory movements should be increased to adapt to the conditions of labor. A pregnant woman should not only concentrate on her respiratory movements and deepening them during inspiration, but also on so-called respiratory phonation during expiration–i.e., making an audible sound during expiration. This is an important aid in labor when dealing with the pain of contractions. Important aspects of breathing in the first stage of labor include: To deal with the contractions of the first stage, the pregnant woman chooses one of the basic positions, from upright to lying down (except supine), in which she can comfortably shape her breathing and movements according to her needs. The proximity of her partner and the midwife give her security. When she is aware of all the aids to inspiration and expiration that are available and knows that she can change her position and the direction of her breathing as she chooses, “breathing to the infant” becomes easier. In inspiration, important concepts are the “hollow space of the mouth” (the yawning position to open the glottis), and the helpful idea of breathing in as if “sniffing” to the infant (turbinates, nasal spaces are widened). Depending on her needs, the pregnant woman can choose for herself whether she prefers to direct her costoabdominal breathing anteriorly, laterally, lumbodorsally, or downward. Similarly, she can regulate the deepening of her respiratory movements “to the baby” herself, depending on the pain of her contractions. For expiration, she can choose slow respiration adapted to her individual work on her contractions and pain; this might involve sighing, making sounds, or groaning. In the interval between contractions, the woman in labor rests, since the first stage can last many hours, especially in a primipara. For this period, many obstetric hospitals nowadays offer carefully furnished and decorated rooms for labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum (LDRP) where the mother, support person, and baby can remain throughout their stay. Mothers and parents appreciate a homely atmosphere in a safe place and tend to choose their obstetric hospital with this in mind. Toward the end of the first stage, the situation changes for the woman in labor. The contractions are stronger and the intervals shorter, while pain, fatigue, exhaustion–and after a long first stage, often loss of motivation–indicate that labor has entered a transition phase for the mother as well as the infant. The start of the transitional phase means that: Occasionally, particularly in multiparous women, full dilation and rotation of the infant’s head into its correct position in the pelvic outlet will happen in a very short period of time, so that the woman can help right away to slide out her baby. These women are spared the transition phase, which most women otherwise experience as the most critical phase of labor. However, most women–especially primiparae–will experience the transition phase. During this phase, the woman will receive instructions not to push, even though an urge to empty is felt. The urge is due to the infant’s head overloading the pelvic floor. However, the sagittal suture has not yet rotated vertically, so that the infant is not ready for delivery. This avoidance of pushing with urge combines with the considerably stronger experience of painful contractions triggering uncontrolled high-frequency breathing and breath-holding at the end of inspiration (inspiratory pause), inducing or aggravating unconscious hyperventilation. In this type of situation, the woman in labor may receive well-meaning but incorrect advice, such as: “Breathe deeply to give your baby enough air (oxygen)” (a request that can trigger fear and worry about the baby), or the woman may be instructed to pant in order to hold back the urge to push. In this situation, voluntary hyperventilation can be intensified by costosternal breathing, perhaps even at a high rate. According to Huch, breathing at the high rate of panting “entails the risk of veering into further hyperventilation.” The author urges: “during prenatal preparation, do not practice breathing at too high a frequency, which can lead to hyperventilation” [Huch 1983]. As an immediate intervention, the person conducting the labor can let a hyperventilating woman breathe into a plastic bag, so that she re-breathes her own expired air (CO2). This allows the effects of hyperventilation gradually to subside. However, when a plastic bag (or glove) is placed in front of a hyperventilating woman’s mouth and nose at a time when the she feels at her physical and psychological limits, panic can ensue. The consequences of hyperventilation [Huch 1983] can be divided into cardiovascular and pulmonary effects. Effects of hyperventilation on the mother: Effects of hyperventilation on mother and baby: Because the acid–base balance is disturbed, alkalosis (an increase in blood pH to over 7.4) develops in the mother, and this leads to changes in the calcium balance. The result is an increase in neuromuscular irritability: a tingling sensation and numbness in the hands, followed by carpal spasm (tetany), distortion of the face with a pale triangular shape of the mouth, and later nausea and panicky anxiety. If the woman in labor hyperventilates more strongly during painful contractions, either spontaneously or following incorrect breathing instructions, hypoventilation or even apnea may ensue during the interval between contractions. The woman simply has no impulse to breathe, because the respiratory center does not provide stimulation to breathe, while the partial pressure of CO2 (Pco2) is below normal. Measurements of the partial pressure of oxygen (Po2) in the infant [Huch 1983] have shown that if the mother hypoventilates following hyperventilation, the infant’s oxygen supply is impaired. Treatment suggestion. In this case, the woman in labor should be advised to breathe quietly “to the baby” during the interval between contractions. Huch reports that it is often sufficient simply to induce the mother to talk (resulting in expiration) between contractions in order to raise and stabilize the mother’s Po2, ensuring the infant’s oxygen supply. It is important for the partner to be instructed that even a woman who is well prepared for labor may “fight” during the transition phase of labor when a contraction is particularly painful. If she complains of numb hands and pins and needles in the fingers, or dizziness during the interval between contractions, the partner must first immediately contact the midwife or nurse and then quietly join the woman in labor in breathing quietly “to the baby,” or ask her to talk. Note that the partner should only ask the woman in labor to talk–she has to do the talking, so that her expiration is reinforced. Situations such as this and others that have been found to be linked to hyperventilation during labor have suggested the need to provide some assistance with breathing during the transition stage of labor as part of prenatal preparation. This type of assistance needs to be designed not to reinforce induced hyperventilation–e. g., through incorrect breathing instructions such as costosternal inspiration (“take deep breaths”) or panting. As a result of their studies, Huch and Saling came to the conclusion that the hyperventilation in a woman in labor affects the fetus [Saling 1980, Huch and Huch 1984]. The risks they demonstrated confirmed the view we had held for many years that rapid breathing (panting) should not be promoted in prenatal preparation [Heller 1998]. Panting is a rapid, shallow type of breathing. In the psychoprophylactic Lamaze method of labor, this breathing method was designed to provide analgesia through hyperventilation [Heller 1998]. Instructions to breathe costosternally, and especially panting (which does not take place in the middle range of the thorax) during the last stage of labor, before the woman is allowed to push with the contractions, have consequences that are not advantageous for the mother and particularly not for the infant (see Fig. 4.4). In order to prevent excessive hyperventilation by a woman in labor during the difficult and painful transitional stage of labor, 30 years ago Ruth Menne introduced “swinging,” as she called it, in order to correct breathing. As she developed it later, breathing in this method starts with expiration, which is emphasized. It later became important to determine whether the many years of positive experience in using “swinging” as a respiratory aid could be confirmed by objective measurements. Women in labor would comment, “Without swinging I would have lost control completely,” and would say to the person conducting the labor, “You do this so well,” while at the same time the method prevented hyperventilation with its detrimental effects on the mother and baby. The cardiotocography (CTG) monitor during delivery indicated a stable oxygen supply to the baby during swinging, as the mother does not hyperventilate. To compare “swinging” and “panting” in pregnant women at term without complications or risks, Dr. Gordt, a pulmonary and bronchial specialist in Mannheim, Germany, generously offered to carry out two case studies in his office using the much easier technical procedures available today. Two healthy pregnant women close to term underwent pulmonary function studies in his office. The purpose of the pulmonary function studies and the procedures used were explained to them. The testing included spirometry and body plethysmography. Both women were then instructed to use the breathing aid “swinging” (Fig. 4.2), after which they were to pant (Figs. 4.3, 4.4) in the currently customary manner to the point of hyperventilation. As the data from both participants– tests were in good agreement, only one of the two sets of measurements are shown here as an example. Unfortunately, no larger-scale studies of this breathing aid are available. To pant, the woman has to take a deep breath and then breathe rapidly, but with small respiratory volumes. She therefore breathes with a greatly expanded chest, and functional residual capacity (FRC) rises from 2.2 L to 4.9 L. By contrast, during “swinging,” which is described below, chest expansion was unchanged and the FRC was only 2.8 L. The advantages for the mother and especially the infant are considerable (Fig. 4.2). The body plethysmographic studies showed impressively that the benefit of “swinging” as a respiratory aid can be demonstrated by objective measurement. “Swinging” during prenatal preparation is a respiratory aid for pregnant women. However, it is especially useful during an intense, prolonged transitional phase, preventing hyperventilation and enabling the woman to deal with intense labor pain and the premature urge to push. Support by the partner is here of major assistance. What is meant by “swinging”? The diaphragm “swings” around its mean position (Fig. 4.4), beginning with a gentle expiration. This movement uses small amounts of air. Each breath in and out is a small amount, which is explained by the following image, the “thimbleful7rdquo;: Swinging with the small amounts of respired air (column of air) proceeds through the mouth. The lips are relaxed and slightly open, the jaw is relaxed. The tongue lies softly on the floor of the mouth. The mouth and pharynx are experienced as a hollow space. This is accompanied by the suggestion that all spaces in the body are “opened” The combined sounds “h” and “ah,” that is “hah,” with soft intonation while swinging the column of air up and down, emerge voicelessly from the spaces of the pharynx and throat. When contractions are being processed, the emphasis on expiration can often be heard as an audible moan. It is important to emphasize expiratory swinging. It should be noted that the rhythm of swinging will be different for each woman. There is no time limit for swinging during a contraction. The woman ends a few up-and-down movements of the column of air with an out (to the respiratory midposition), then takes a thimbleful in for the baby (within the limits of resting respiration), ready to begin a new swinging cycle with an emphasized out, etc., until the contraction is over. First step According to Middendorf [1990], all vowels have their own space in the body in which they expand and reside. The space of the vowel “a” moves the lateral thorax on both sides as far as the axilla. The ribs are raised and lowered. Position Procedure Breathe voicelessly: out—in—out—in—out First step: a—hah—a—hah—a, etc. Second step: haah—hah—haah—hah—haah, in a rhythm that is comfortable for each individual, until the “internal column of air” swings up and down.

4.1 Swinging and Sliding—Back-to-Nature Labor: a Safer Method for Mother and Child

Prenatal Care: Preventive Care for the Pelvic Floor During Labor

Prenatal Care: Preventive Care for the Pelvic Floor During Labor

Breathing during the First Stage of Labor

Breathing during the First Stage of Labor

N. B. An individual’s respiration is always an expression of his or her current physical condition.

N. B. An individual’s respiration is always an expression of his or her current physical condition.

N. B. An important source of psychological motivation, which the birth attendant and partner can repeatedly remind the woman about, is that each contraction is moving her toward the goal of having her baby and holding it in her arms soon.

N. B. An important source of psychological motivation, which the birth attendant and partner can repeatedly remind the woman about, is that each contraction is moving her toward the goal of having her baby and holding it in her arms soon.

Breathing during the Transition Phase and the “Swinging” Respiratory Aid

Breathing during the Transition Phase and the “Swinging” Respiratory Aid

Effects of Hyperventilation

Effects of Hyperventilation

Cardiovascular Consequences of Hyperventilation (Heart and Circulation)

Pulmonary Effects of Hyperventilation

Causes of Hypoventilation in the Interval between Contractions

Swinging Versus Panting

Swinging Versus Panting

“Swinging” as a Possible Aid to Breathing in the Transitional Stage

“Swinging” as a Possible Aid to Breathing in the Transitional Stage

Advantages of “Swinging”

Learning and Practicing “Swinging”

Teaching the Practice of “Swinging”

Example

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree