R. Michael Meneghini

Arlen D. Hanssen

Surgical Management of the Infected Total Hip Arthroplasty

INTRODUCTION

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) remains one of the major complications that can ensue following total joint arthroplasty, with an incidence of 1% to 2% at 2 years postoperatively for both total hip and knee arthroplasty1,2 and up to 7% after revision surgery.3 Deep PJI in total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a devastating complication, while the complexity and duration of treatment impart significant physical, emotional, and financial costs to both the patient and treating physicians.4,5

An accurate and expedient diagnosis in the face of subtle clinical signs is mandatory for the treating physician. Decisions regarding treatment are multifactorial and patient specific. Multiple treatment options have been described for the management of an infected THA, including long-term antibiotic suppression, surgical debridement with component retention, one-stage or two-stage exchange, excision arthroplasty, arthrodesis, and hip disarticulation. This chapter focuses on the surgical management of periprosthetic infection in THA, while the etiology and diagnosis of periprosthetic sepsis are covered in detail in Chapter 53.

TREATMENT METHODS WITH COMPONENT RETENTION

Antibiotic Suppression with Component Retention The concept of component retention with antibiotic suppression has been investigated in numerous reports. Although the indications are limited for chronic suppression and component retention for deep periprosthetic THA infections, there still may be a small subset of patients that may be appropriate for or desire this treatment modality.

Antibiotic suppression and prosthesis retention can succeed in some patients and may be considered in elderly debilitated patients with an early infection caused by bacteria responsive to oral antibiotic therapy. Suppressive therapy may also be considered for an otherwise compliant patient who refuses removal of an infected prosthesis. The organism must be sensitive to oral antibiotics, and the patient must be tolerant of the antibiotics.6

Antibiotic treatment alone will not eliminate deep periprosthetic infection but can be used as suppressive treatment when the following criteria are met: (i) prosthesis removal is not feasible due to the patient’s medical condition or other reason, (ii) the microorganism has low virulence, (iii) the microorganism is susceptible to an oral antibiotic, (iv) the antibiotic can be tolerated without serious toxicity, and (v) the prosthesis is not loose.7 The presence of other joint arthroplasties or a cardiac valvular prosthesis is a relatively strong contraindication to chronic antibiotic suppression as a treatment choice.

One of the largest series in the literature was that of Goulet et al.,6 where they examined the effectiveness of antibiotic suppression in 19 deep periprosthetic hip infections. Indications included patients’ refusal of removal or medical contraindications to surgery. Requirements included well-fixed components, highly sensitive organisms, and no systemic sepsis. The follow-up period averaged 4.1 years after treatment and nine hips showed no deterioration, while seven prostheses failed, five of which demonstrated progressive hip sepsis. The authors concluded that in a very select patient population and known low-virulence organisms, this treatment displayed some utility in their small series. Antibiotic suppression with component retention may also be considered for medically infirm patients or elderly with massive bone loss that would preclude adequate reconstruction options. However, it should be emphasized that this treatment option should be used with caution, and the indications are limited as antibiotic suppression can lead to development of bacterial resistance and component retention can further complicate future infection eradication efforts.

Surgical Debridement with Component Retention Surgical irrigation and debridement with component retention and supplemental antibiotic therapy are often accompanied by exchange of the polyethylene insert and associated femoral head exchange. This treatment option initially appears attractive to the patient and surgeon alike for several reasons that include low morbidity compared to a two-stage resection arthroplasty requiring multiple procedures, the desire by the patient to retain the prosthesis in many cases, a potentially falsely optimistic attitude about the effectiveness of current antimicrobial agents, and the impression that a failed attempt causes little harm.8 Because of this initial attractiveness, surgical debridement and component retention are an established treatment in practice and have been studied and reported extensively.

However, the reported success rates for prosthesis retention in the literature are highly variable due to a lack of consistency in the definition of what is considered acute infection, studies containing multiple surgeons, and studies with nonconsecutive series of patients. Furthermore, the literature is skewed as to component retention effectiveness when depth of infection is included as a diagnostic variable, as studies have suggested improved results with acute superficial infections in contrast to deep infections.9, 10

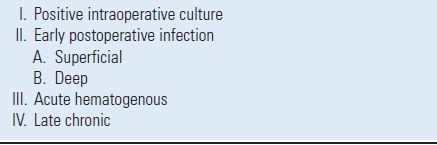

Periprosthetic infections are classified as positive intraoperative culture, early postoperative, acute hematogenous, or late chronic infection according to their duration of involvement and proximity to the preceding joint arthroplasty11 (Table 30.1). While many authors define acute postoperative infections as occurring within 4 weeks from surgery, others have considered this time period to be as short as 2 weeks and as long as 3 months.9,12,13

TABLE 30.1 Classification of Deep Periprosthetic Infection on the Basis of Clinical Presentation

To our knowledge, the report by Azzam et al.14 is the largest series in the literature that examined open irrigation and debridement for the management of PJI. One hundred four patients (44 males and 60 females) were identified with an average follow-up of 5.7 years. Treatment failure was defined as the need for resection arthroplasty or recurrent microbiologically proven infection. According to these criteria, irrigation and debridement were successful in only 46 patients (44%). Patients with staphylococcal infection, elevated American Society of Anesthesiologists score, and purulence around the prosthesis were more likely to fail.14 Another study examined the medical records of 18 patients with acute periprosthetic infections occurring within 28 days after thirteen THAs and five TKAs.10 The mean time to reoperation was 19 days after arthroplasty. At the last follow-up, retention of the hip or knee prosthesis was successfully achieved in four of five patients with superficial (extrafascial) infections compared to eight of thirteen patients with deep prosthetic infections.10

Similarly, Crockarell et al.8 cited 42 hips managed with open debridement, retention of the prosthetic components, and antibiotic therapy. After a mean duration of follow-up of 6.3 years, only six patients (14%), four of nineteen with an early postoperative infection and two of four with an acute hematogenous infection, had been managed successfully. This study and others have revealed a time-dependent success rate in achieving infection eradication when debridement and component retention are employed. Brandt et al.15 found a cure rate of 56% following debridement within 2 days of symptom onset, compared with only 13% when carried out >2 days after the onset of symptoms. Yet another series examined the effectiveness of arthroscopic lavage and debridement in the management of eight (8) acute THA infections.16 Infection eradication was successful in all patients at an average of 6 years’ follow-up. The authors attributed their success to strict selection criteria. Patients were promptly diagnosed and treated, grew low-virulence organisms, and were compliant in taking long-term oral antibiotic therapy. The organism responsible for infection also has been shown to be predictive of treatment outcome. The window of opportunity for a successful debridement is even less when the offending organism is Staphylococcus aureus. Brandt et al.17 found prostheses debrided more than 2 days after onset of symptoms were associated with a higher probability of treatment failure than were those debrided within 2 days of onset.

Ideally, treatment of the infected THA with surgical debridement and component retention has the greatest efficacy if confined to PJIs that are either acute or acute hematogenous, that are detected within 2 days of symptom onset, and whose offending organism is of low virulence. This treatment modality in the face of chronic infection is most likely doomed to failure in the majority of cases.

TREATMENT METHODS WITH COMPONENT REMOVAL

One-Stage Exchange In Europe and limited parts of the United States, single-stage (direct-exchange) revision arthroplasty is a viable option to treat patients with an infection at the site of a THA. The reinfection rates after direct-exchange arthroplasty have been noted to be higher than those utilizing the two-stage treatment protocol.18 The single-stage or direct-exchange protocol has not been embraced by most American orthopaedic surgeons, largely due to the lack of randomized trials comparing the two treatment techniques. While the major disadvantage is potentially higher reinfection rates, purported advantages include decreased morbidity, decreased recumbency between procedures found with the two-stage approach, and a technically easier treatment strategy to that of two-stage protocols. The economic impact imparted by the two-stage approach has led to continued research of direct exchange, especially in countries that have national socialized medical systems.

Reports exist that have displayed some encouraging results in eradication of PJI after THA with single-stage or direct-exchange arthroplasty. Callaghan et al.19 reported on 24 one-stage revision surgeries for septic failure of a THA in 24 patients. Infection reoccurred around two hips (8.3%). They concluded that direct exchange was reasonable and cost-effective as long as the method and select criteria were upheld. Their method and criteria included (i) patients without draining sinuses, (ii) patients without immuno-compromise, (iii) patients with adequate bone quality after meticulous debridement, (iv) the use of antibiotic-impregnated cement, and (v) the use of 3 to 6 months of postoperative oral antibiotic therapy.

Similarly, Ure et al.20 performed 20 one-stage revision surgeries for THA PJI. Three patients had a draining sinus tract at the time of the procedure. The methodology included meticulous debridement, administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy, and the use of antibiotic-impregnated cement. At an average of 9.9 years postoperatively, no patient had recurrence of infection. Two patients had revision for aseptic loosening. The authors commented on their relatively small study cohort but stated that this treatment modality in carefully selected patients resulted in successful outcomes. Nagai et al.21 performed the largest series consisting of 162 cases with a mean follow-up of 12.3 years. In this series, eradication of infection occurred in 85.2% of the patients, with 12.3% requiring further revision for recurrent infection.21 One study comparing single-stage versus two-stage exchange favored the two-stage procedure. Elson22 had a 12.4% rate of failure with the single-stage method, compared to 3.5% with the two-stage procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree