Subacromial Decompression: Lateral and Posterior (Cutting Block) Approach

Kevin D. Plancher

David B. Dickerson

Elizabeth A. Kern

Arthroscopic subacromial decompression is a safe and effective technique to treat impingement syndrome refractory to conservative management. Two techniques have been described to resect the anteriorinferior acromion, subacromial bursa, and release the coracoacromial ligament and thus increase the volume of the subacromial space. The lateral approach was initially described by Ellman in 1988. Sampson subsequently described a posterior approach commonly referred to as the “cutting block” technique. Good to excellent outcomes of refractory impingement syndrome treated with arthroscopic subacromial decompression have been reported in up to 88% of patients.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Introduction

Impingement syndrome is a common cause of shoulder pain, which often leads to a decreased ability to perform athletic and daily activities. Subacromial decompression has been used to treat impingement syndrome refractory to conservative treatment since Neer’s description of an open procedure in 1972. Neer (1) described a procedure to increase the volume of the subacromial space and relieve external compression of the rotator cuff by combining debridement of the subacromial bursa with resection of the coracoacromial ligament and the anteriorinferior acromion (acromioplasty). A 25-year follow-up study reported 88% positive patient satisfaction after open acromioplasty (2). However, there has been a general trend to perform procedures using minimally invasive techniques and return patients to their normal activities sooner. Since Ellman’s description of an arthroscopic technique in 1985, the arthroscopic skills of many surgeons and technology have improved leading many surgeons to transition from an open to an arthroscopic approach to accomplish the same goals with comparable results (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10).

Although equipment needs are greater, arthroscopic subacromial decompression offers several important advantages to the open procedure. Arthroscopy allows for the evaluation of underlying intra-articular and extraarticular pathology that can be treated concurrently. The smaller incisions needed for arthroscopic portals cause minimal disruption to the deltoid muscle insertion, allowing for a quicker rehabilitation, less postoperative pain, improved cosmesis, and most importantly, allowing patients an earlier return to activities and sports.

Two arthroscopic techniques have been popularized that resect the anteriorinferior acromion. The lateral technique described by Ellman (6) and the “cutting block” technique described by Sampson (11). There is no clear benefit to either technique and different patient outcomes have never been reported. Techniques used are based on surgeon preference. We advocate the use of the lateral technique, but recommend learning both techniques.

Anatomy/Pathoanatomy

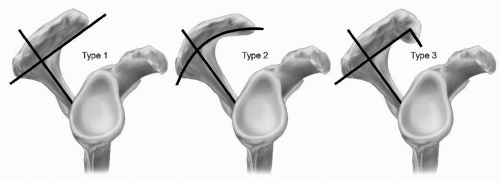

Understanding the relationship between the bony anatomy and the interposed subacromial bursa is essential for the diagnosis of an impingement syndrome and avoiding complications during surgical intervention. The relevant bony structures include the acromion, coracoid process, distal clavicle, acromioclavicular joint, and the greater tuberosity of the humerus. The shape of the anterior acromion has been attributed to the symptoms caused by external impingement. Bigliani (12) described three acromial shapes: type I (flat), type II (curved), and type III (hooked) (Fig. 6.1). A type III acromion decreases the subacromial space and is associated with underlying rotator cuff tears. The acromial type is best evaluated with a supraspinatus outlet view radiograph and aids in planning the amount of the undersurface of the acromion that is surgically resected to establish a flat acromion.

Abnormalities in soft tissues structures around the shoulder are associated with external impingement. The important soft tissue structures relevant are the coracoacromial ligament and the subacromial bursa. The

subacromial bursa lies between the undersurface of the acromion and the superior surface of the rotator cuff. Inflammation of the subacromial bursa leads to a decrease in the subacromial space due to hypertrophy and pain with overhead movements. The coracoacromial ligament extends from the coracoid process to the anterior aspect of the acromion. Hypertrophy of the coracoacromial ligament also causes a decrease in the subacromial space and subsequent impingement. We believe the release of the coracoacromial ligament and a thorough subacromial bursectomy are essential for an arthroscopic subacromial decompression.

subacromial bursa lies between the undersurface of the acromion and the superior surface of the rotator cuff. Inflammation of the subacromial bursa leads to a decrease in the subacromial space due to hypertrophy and pain with overhead movements. The coracoacromial ligament extends from the coracoid process to the anterior aspect of the acromion. Hypertrophy of the coracoacromial ligament also causes a decrease in the subacromial space and subsequent impingement. We believe the release of the coracoacromial ligament and a thorough subacromial bursectomy are essential for an arthroscopic subacromial decompression.

History and Physical Examination

Patients often relate a history of a gradual and progressive onset of symptoms located in their shoulder noted while performing overhead activities or when placing an arm in their coat. Frequently, patients will also complain of weakness and limitations of shoulder movement as a result of this shoulder pain. Many individuals cannot reach to put on their seatbelt or reach items in the back seat of their car. Some patients complain of sudden pain after a traumatic event or when pursuing a new sport. Pain due to impingement is most commonly localized to the anterolateral aspect of the acromion. Patients will often wake at night due to this pain or have difficulty sleeping on the affected shoulder. Although anterolateral shoulder pain is not specific for impingement syndrome, it guides the examiner to a spectrum of disorders of the rotator cuff and the subacromial space.

An insidious onset of symptoms due to extrinsic impingement is more commonly seen in athletes and workers that perform activities with repeated overhead motion. The traumatic onset of an impingement syndrome can be seen after a direct blow to the superolateral aspect of the shoulder or an axial load on the upper extremity, compressing the humeral head into the inferior aspect of the acromion (snow skiing fall, a football or hockey player poorly fitted shoulder pads). The resultant inflammation of the subacromial bursa or contusion of the underlying rotator cuff causes the discomfort noted with overhead motion.

The physical examination is the key to making the diagnosis of an impingement syndrome. In order to perform an adequate examination, the patient must wear a shirt that allows for inspection of the neck, shoulder, and periscapular musculature. The exam should begin with an evaluation of the cervical spine and shoulder girdle. Limitations in neck range of motion, pain reproduced with provocative testing of the cervical spine, and pain radiating from the neck into the shoulder may indicate underlying cervical pathology and should not be confused with an impingement syndrome. The shoulder contours and musculature should be compared with the contralateral shoulder observing any muscle atrophy or squaring of the shoulder girdle. Changes in the resting position, contours, or atrophy of shoulder musculature indicate a possible neurological cause for abnormal shoulder motion resulting in secondary impingement. Tenderness localized to the subacromial bursa and rotator cuff, anterior or anterolateral to the acromion, and along the coracoacromial ligament is a common finding noted in patients who have extrinsic impingement syndrome.

Active forward flexion and abduction of the shoulder is frequently limited secondary to pain. However, passive range of motion must be tested to adequately assess terminal pain in forward flexion and/or abduction to ensure that the diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis is not made in error. Strength testing may also be limited due to pain and may suggest rotator cuff dysfunction, specifically with supraspinatus and infraspinatus testing differentiated with a lidocaine test. Subtle dynamic scapular winging of the shoulder during range of motion may be present. This denotes scapular dyskinesis, although it will not distinguish impingement as a primary or secondary condition.

Several tests have been described to aid in the diagnosis of an impingement syndrome. The “impingement sign” initially described by Neer, along with the Hawkins-Kennedy test, the painful arc sign, and the infraspinatus muscle test, offer the high sensitivity and specificity needed to distinguish this disease. The Neer sign is positive when pain at the anterior or lateral edge of the acromion is produced when the examiner stabilizes the scapula and passively forward flexes the arm with the humerus internally rotated. Hawkins and Kennedy described an alternative impingement test. This test is positive when pain is reproduced with forward flexion of the humerus to 90° and gentle internal rotation of the shoulder. These tests place the greater tuberosity, rotator cuff, or biceps tendon against the undersurface of the acromion or coracoacromial ligament causing aggravation of an inflamed subacromial bursa. The Neer sign has a sensitivity and specificity of 68.0% and 68.7%, respectively. The Hawkins-Kennedy sign has a slightly higher sensitivity (71.5%) and slightly lower specificity (66.3%). The sensitivities increase when patients without underlying rotator cuff disease are excluded.

A third test, the painful arc sign, has a sensitivity of 73.5% and specificity of 81.1%. This test is positive when a patient has pain or painful catching between 60° and 120° of elevation when actively elevating the arm in the plane of the scapula. The infraspinatus muscle test also has diagnostic value with a sensitivity of 41.6% and a specificity of 90.1%. This test is performed with the arm adducted to the side and the elbow flexed to 90°. The patient is then asked to resist an internal rotation force. A test is considered positive if the patient gives way due to pain or weakness, or has an external rotation lag sign. The likelihood of an impingement syndrome is >95% if the Hawkins-Kennedy impingement sign, painful arc sign, and infraspinatus muscle test are all positive. If these three tests are all negative, the likelihood of an impingement syndrome is <24% (13). Confidence in the diagnosis can be improved with the lidocaine test. Injection of 10 mL of lidocaine into the subacromial space through an anterior approach (as this is where the pathology lies) often alleviates the patient’s symptoms. The alleviation of symptoms during provocative testing after injection confirms the diagnosis of an impingement syndrome.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiographic evaluation of the shoulder is essential to evaluate the shape of the acromion and rule out concomitant pathology. A true anterior-posterior radiograph of the shoulder allows assessment of the glenohumeral joint. To obtain this view, the body is rotated 35° toward the side of the involved shoulder, and the scapula is placed flat against the film. This position places the glenoid perpendicular to the X-ray beam and allows for the assessment of the glenohumeral joint to note any arthritic changes. A second view, the supraspinatus outlet view, allows for the assessment of acromial morphology and is essential for preoperative planning. We advocate a repeat supraspinatus outlet view postoperatively to evaluate the acromial shape after arthroscopic acromioplasty (Fig. 6.2A and B). This view is obtained by positioning the patient for a scapular lateral view and tilting the X-ray beam caudally 10° to 15°. Additional routine radiographs of the shoulder that may be helpful include the axillary view and Zanca view. The axillary view further evaluates the glenohumeral joint and acromion and more importantly, may reveal an os acromiale. The Zanca view is best to evaluate the acromioclavicular joint for arthrosis or any incongruity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree