Fig. 29.1

The most relevant sign was the stone-hard skin induration of buttocks and thighs

Differential Diagnosis

SSS is a diagnosis of exclusion, with a distinctive clinical presentation without pathognomonic laboratory or pathological findings. The clinical differential diagnosis of stone-hard and thickened skin areas includes systemic sclerosis, overlap syndromes (e.g., sclerodermatomyosists), morphea, scleroderma, eosinophilic fasciitis, and scleromyxedema. The appearance of the disease in early childhood, the limitation of joint mobility, the proximal rather than a distal stiffness, and the absence of organ involvement are the main clinical findings that differentiate SSS from systemic sclerosis. Moreover, microvascular abnormalities, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and autoantibodies were absent in SSS. Several features can help differentiate SSS from scleredema. In SSS, disease is centered on or around the pelvic and shoulder girdle, whereas scleredema is centered on the face, head, neck, and back. Joint restriction, although common in SSS, is rare in scleredema and is more often due to a “bulk” effect of the thick skin usually affecting the eyelids, neck, mouth, and shoulder. The skin stiffness in SSS is often well demarcated, uneven, or lumpy and may not involve an entire anatomic unit, while the stiffness in scleredema is more uniform, typically encompassing an entire involved anatomic unit. The abrupt onset often seen in scleredema is not a feature of SSS.

Sclerodermatomyositis presents with arthralgias, arthritis, sclerodermoid skin lesions, and joint restriction. Features that distinguish this entity from SSS are evidence of muscle involvement, autoantibodies, and vascular hyperreactivity. Localized scleroderma (morphea) tends to have a later onset as well as more localized and asymmetric indurations and alterations of the skin. Generalized morphea, a form of localized scleroderma, must also be distinguished from SSS. In deep morphea, there is typically a lymphocytic or lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate at the junction of the dermis and subcutis with abnormal, sclerotic collagen in the deep reticular dermis or subcutaneous septa, and fascial involvement is exceptional. In addition, many of the clinical features of SSS, such as the characteristic distribution involving the pelvic area and/or shoulder girdle and the often-present hypertrichosis, are typically not observed with generalized or localized morphea. Eosinophilic fasciitis classically presents with rapidly appearing tender swelling on the arms and legs evolving into brawny induration, often following exertion. Localized morphea-like skin changes and joint contractures may be present, and the induration is often more distal than proximal. Hematologic abnormalities including peripheral blood eosinophilia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate are often present. Histopathologic findings demonstrate thickened fascia with a cellular inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells, with or without eosinophils.

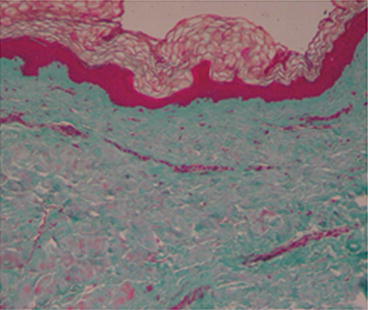

Biopsy

Several histologic patterns have been described in literature. Early reports described increased dermal mucin and large, bizarre fibroblasts that stained metachromatically with toluidine blue. Jablonska described underlying fascial thickening as “four times beyond normal” with “amianthoid-like” collagen fibers and bundles composed of incompletely organized microfibrils. Several subsequent reports confirmed a thickened fascia, but others reported normal fascia. In the SSS dermis (Fig. 29.2), Guiducci et al. [11] clearly showed an increase of fibrotic molecules (col1A2, fibronectin-1, and thrombospondin-1) and the presence of irregularly distributed collagen bundles, flattening of dermal papillae, and absence of sebaceous glands (Fig. 29.3); inflammatory mediators (IL-6, IL-1b, FGFR-3, and MCP-1) were downregulated in agreement with the absence of dermal inflammatory infiltrates (Fig. 29.4); no differences in pro-fibrotic cytokines (TGF-b, ET-1, and CTGF) were detected; and a loss of microvessels was clearly evident at the dermal–epidermal junction and in the papillary dermis, despite the overexpression of VEGF found in the dermis. In a previous work, circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-_ and TGF-b2) were found to be increased, whereas collagen production and DNA biosynthesis were normal [12]. In agreement with other authors [12], Guiducci et al. [11] did not report mucopolysaccharide deposits in the dermis. However, Geng et al. [13] reported mild deposits of mucopolysaccharides between the collagen bundles throughout the dermis, hypothesizing that SSS could be a localized form of mucopolysaccharidosis.