Chapter 38 Sports Knee Rating Systems and Related Statistics

General Outcome and Quality of Life Scales

Medical Outcomes 36-Item Short Form Health Survey

The medical outcomes 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a common general health questionnaire used in health science research that includes 36 questions about general health status. This generic general health scale is not specific to a disease or pathology and therefore allows for wide-ranging comparisons across patient populations.44 It is also available in a shorter 12-item form, known as the SF-12, which shares all 12 of its items with the SF-36. Both the SF-12 and SF-36 have been shown to be reliable and valid when administered in several languages both in person and via telephone, and are easily compared with previously established normative values.22,45 Research14 has shown that these scales are most reliable when administered in subjects between the ages of 18 and 75 years, and the SF-12 may be more appropriate when used in studies with large sample sizes. Currently, these scales have been used widely in research involving knee and hip osteoarthritis, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, patellofemoral pain syndrome, and other sports injury populations.19,23,39,40

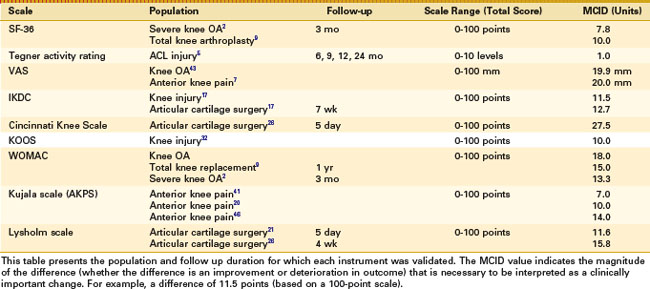

The SF-36 and SF-12 scales consist of eight subscales (physical function, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health), which allow for individual scoring as well as calculation of a physical and mental composite score.44,45 Composite and subscale scoring are based on a 0 (worst health) to 100 (most healthy) scale. The SF-36 has shown better specificity (Table 38-1) and is less likely to experience floor and ceiling effects in injured populations whereas the SF-12 offers easier scoring and a shorter amount of time to administer.48 Most commonly, this scale is used in combination with a more region-specific or injury-specific scale to allow for a more global assessment of patients’ general health status in conjunction with region-specific function through the use of another outcome instrument.

Global Rating of Change

The global rating of change (GROC) scale is a PRO instrument that allows for simple tracking of patient outcomes by determining how much better or worse the patient is feeling after an injury, treatment, surgery, and so on. The GROC scale can have multiple forms. One commonly used GROC form consists of the rating of change consists of a 15-point scale, ranging from patients reporting they feel “a great deal worse” (positive values, maximum +7) to great decrement (negative values, minimum −7). A score of 0 means that the patient has perceived no change in his or her condition.12,35

Scoring of the global rating of change varies throughout the literature and can be manipulated to fit the research question at hand best. In many cases, a value of −7 is assigned to the descriptor of greatest decrement whereas a value of +7 is assigned to the descriptor of greatest improvement.12,35 This scoring system allows for easy comparison of patient-reported changes over time with regard to function, symptoms, and affective outcome measures. Its use can be modified based on the question asked. For example, a patient can provide a global rating of change score when asked, “How would you rate your outcome following your shoulder surgery?” Clearly, the scale can be used for various conditions and patient groups at various time points following injury or surgery to provide an overall (global) understanding of how a patient perceives the outcome following their injury, condition, or procedure.

Currently, this rating scale is most commonly used in research involving surgical interventions, knee osteoarthritis, and patellofemoral pain.7,34 Although this scale allows for a easy comparison over time, it is generally combined with a region- or pathology-specific scale, such as the SF-36 and SF-12, to provide a more comprehensive review of patient outcome. No minimal clinically important differences have yet been established for this scale in patients with knee pathology because of the wide scope of populations and injury severities represented.

Visual Analogue Scale

The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) is possibly the most easily understood and widely used pain rating scale in clinical research. Although there are many iterations of this scale, the concept remains consistent throughout. In general, patients are asked to place a mark intersecting a 100-mm line with two polar descriptors—for example “no pain” on one end and “worst imaginable pain” on the other. Patients make a mark along the line at the point between the two polar descriptors that represents their current level of pain or discomfort. The distance (in millimeters) from one end of the scale (the zero point, or the point representing no pain) is then measured to represent the subjective level of pain perceived by the patient. Other VAS scales will ask to identify a number from 0 to 10 that represents their current level of perceived pain at a specific time or during an activity.10 In many cases, more than one VAS can be used to characterize better the pain experienced by the patient. These scales include such questions as current pain, worst pain in the previous 24 hours, worst pain during work-related activity, average pain over the previous 24 hours, and least pain in the previous 24 hours. Although these are representative of some commonly used scales, the questions used can easily be altered to attain a better fit of the patient population and pathology being studied.

The VAS has been shown to be valid and reliable in many forms throughout the literature and often is used as a gold standard when attempting to validate a new assessment instrument.* Sensitivity is highly variable, depending on the scale used and the population in which the measurement is taken. This flexibility is a strength of the VAS but results in difficulty when attempting to show clear cutoff points for patient improvement. Currently, minimal clinically important differences have been shown in patients with knee osteoarthritis, hip osteoarthritis, and anterior knee pain, reported as 19.9, 15.3, and 20.0 mm, respectively (Table 38-1).

The VAS has been used as a framework for knee-specific outcomes scales. For example, the Knee Disorders Subjective History10 has been used to characterize function following knee joint injury or surgery. This scale involves 28 questions about knee joint function during specific activities. It is a series of visual analogue scales with different polar descriptors that enable patients to rate their function from best to worst for each specific question. For example, the question, “Do you feel grinding when your knee moves?” is rated on a 10-point scale ranging from none to severe; the question, “Is your knee stiff?” is rated on a 10-point scale ranging from none to “I can barely move my knee due to stiffness.” Questions can be reviewed individually or assigned a specific score (from 1 to 10) for each of the 28 questions and then combined for a total score, normalized to 100%, which represents highest possible function.

Another VAS-based knee-specific outcome score was proposed as a general quality of life outcomes score specific to patients with ACL deficiency. The ACL deficiency quality of life (ACL-QOL) measure27 incorporates scores from a series of visual analogue scales (100-mm lines with polar descriptors) for 31 total questions. Scores for each question are combined to form a single score on a 100% scale in which 100% indicates highest function or quality of life in ACL-deficient patients. The scale is divided into subsections that ask specific questions about symptoms and physical complaints (four questions), work-related concerns (four questions), recreational activities and sports participation or competition (12 questions), lifestyle (six questions) and social and emotional (five questions). ACL-deficient patients who scored low on this scale were more likely to go on to have reconstruction surgery compared with patients who scored high.

Tegner Activity Scale

The Tegner activity scale was developed in 1985 as a patient-reported score describing typical daily activities. This scale offers patients the choice of 10 distinct levels. The patient provides a rating (values are from 0 to 10, with 10 indicating the highest level of activity) for current level of activity and level of activity prior to injury.42 The available ratings are broken into four distinct regions, with a rating of 0 corresponding to disability caused by knee problems, 1 to 5 representing levels of work-related activity and recreational sport, 6 to 9 representing competitive and higher levels of recreational and organized or competitive sports, and 10 representing the highest and most elite international or professional level competitive sport. These levels, depending on the population of interest, may not adequately represent the spectrum of daily function and activity and therefore may not allow for clear comparisons among patients. In practice, this scale is commonly associated with the Lysholm score and can allow for a reasonable characterization of patient activity levels, especially when measured in a preinjury, physically active population. Currently, this scale has been shown to be valid and reliable in patients with meniscal injury, patellar instability, and ACL injury.4,5,33 In patients with ACL injury, a minimal clinically important change of 1.0 has been established. This suggests that a change in activity rating following ACL injury of at least 1 point needs to be met for the change to be considered clinically important. When the scale is used for young patients involved in high levels of activity, it is important to note that transitions from the higher ratings (competitive or elite sports) to lower levels (work and recreational activity) may reflect the natural course of time as an athlete graduates from competitive sports and begins to pursue other professional or life interests. Whether this change is the result of injury or other noninjury-related factors is a potential limitation to the interpretation of this score.

Knee-Specific Outcomes Scales

International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form

The International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form (IKDC) was developed as a standardized assessment tool for knee injury and treatment. It was first published as a patient-reported outcome measure in 1993 and revised to its current form in 1997. This scale is knee-specific but allows for measurement of subjective outcomes of various pathologies. Currently, the IKDC includes 18 total items, those regarding symptoms (7 items), general function (2 items), and sport activities (9 items).16 Patients are encouraged to complete all of included items; however, scoring is possible as long as 16 of 18 items are completed. Following completion, the scores are converted to a 100-point scale with 100 representing the best possible score and highest knee function. The strength of this rating scale lies in the diversity of items regarding patient-reported knee joint symptoms and function during activities that specifically involve the knee joint (e.g., walking, jogging, stair climbing), which allows for a better representation of the limitations or improvements that may be expected in different populations and pathologies.

The IKDC has been shown to be reliable and valid for a number of pathologies, including ACL injury, meniscal injury, articular cartilage injury, patellofemoral pain syndrome, and knee osteoarthritis.1,15,17 Normative values have been established to allow for easy comparison of healthy and pathologic populations. A minimally important difference of 11.5 has been suggested but has not been validated in all pathologic populations (see Table 38-1). This form is available in several languages and can be completed in less than 10 minutes. The IKDC represents a clear and concise assessment tool for knee-related research that can be applied across pathologies and population characteristics.

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) was developed to assess symptoms and function in patients with lower extremity osteoarthritis. This scale is composed of 24 items divided among three subscales—pain (5 items), stiffness (2 items), and function (17 items). Each item asks the patient to provide a Likert rating (none, mild, moderate, severe, or extreme) in response to each item. Each item is scored and combined in total or within each subscale and normalized to a 100-point scale, in which a score of 100 represents no symptoms and a score of 0 represents the worst symptoms.38,48 The WOMAC is most commonly used for assessing changes in patient reported outcomes related to post-traumatic osteoarthritis in older populations but has been used more broadly to measure changes in symptoms and subjective outcomes in a spectrum of knee injuries.3

The WOMAC has become the most widely reported subjective outcome measure for patients with lower extremity osteoarthritis and has been shown to be valid, reliable, and sensitive to change over time.3 Minimal clinically important difference has been established as 9.1 in the knee osteoarthritis (OA) population, indicating that the total WOMAC score must change by a minimum of 9.1 points for the change to be clinically important. This difference has also been calculated when the WOMAC is compared with the SF-36 in a rehabilitation population, with 12% at baseline and a 6% difference at maximum score considered to be important.2 This value has not been validated in other populations but may act as a benchmark for comparison within the population of OA patients. The WOMAC is currently available in several languages and several methods of administration and has been shown to take an average of 10 to 15 minutes to complete.48,49 Although the WOMAC has several strengths and weaknesses, its widespread use in the knee and hip OA literature makes it an important consideration when assessing PRO in patients with OA.

Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) was first published in 1998 and was developed as a patient-reported instrument to assess subjective opinion regarding knee injury. As the name implies, this scale is used in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Aptly, the KOOS includes the pain, stiffness, and function sections of the WOMAC scale, which allows for easy comparison of KOOS and WOMAC scores. This scale is directed toward knee injury that can result in post-traumatic OA and allows for prospective assessment of subjective functional and sport-specific outcomes.36,38 The KOOS consists of 42 items divided into five subscales; pain (9 items), symptoms (7 items), function in daily living (17 items), knee-related quality of life (4 items), and function in sport and recreation; these are scored on a 5-point Likert scale. After completion, each subscale is normalized to a 100-point scale, in which a score of 100 represents no symptoms and a score of 0 represents the worst possible symptoms. The KOOS generally requires 10 to 15 minutes to complete and is available in several languages.

Validity and reliability of the KOOS have been established in patients following ACL reconstruction, partial meniscectomy, and tibial osteotomy, and OA.8,36–38,47 It has been reported that a change of 8 to 10 points on a transformed subscale score may represent the minimal clinically important difference. The KOOS has been shown to be most sensitive to change in young active populations, with greatest responsiveness on the function in sport and recreation and knee-related quality of life subscales. Despite this fact, the KOOS has been used in the literature in wide range of ages (18 to 78 years) and levels of physical activity. Reference values for the healthy population stratified by age and gender are available and allow for easy comparison between healthy and pathologic populations.36

Kujala Anterior Knee Pain Scale

The Kujala scale, or anterior knee pain scale (AKPS), is a patient-reported, knee-specific scale that was developed in 1993 for patients with anterior knee pain. This 13-item scale contains questions related to symptoms reported by patients both at rest and during specific functional tasks, including walking, running, jumping, squatting, sitting for long periods of time, and stair climbing. Each item in the AKPS includes specific responses from which the patient can choose; each is assigned a point value to allow for easy scoring. The AKPS is based on a 100-point scale, with a score of 100 representing pain-free function and a score of 0 representing the maximum presence of pain, and therefore worst function.24

The AKPS has been shown to be valid and reliable in differentiating the difference in severity of anterior knee pain as well as the effect of treatment on anterior knee pain. Sensitivity has shown to be good to excellent in most cases, with the exclusion of differentiating among patients with repetitive patellar dislocation and those with one-time dislocations.33 This may be because of the lack of questions relating to the progression of the patient’s condition, with exhaustive focus instead on the effects of the condition on daily symptoms and function. Minimal clinically important differences have been established in three different studies at a value of 7, 10, and 14 points, respectively20,41,46 (see Table 38-1). In all cases, these differences were reported as improvements over time or following treatment. The AKPS is a widely used scale, both clinically and in clinical research, for monitoring longitudinal changes in patient-reported symptoms and function, and should be considered when attempting research regarding anterior knee or patellofemoral pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree