Splinting, Orthoses, and Prostheses in the Management of Burns

R. Scott Ward

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

2. Describe how wound care may affect the use and application of splints, orthotics, and prosthetics.

4. Describe the use of splints and orthotics in the care of patients with burn injuries.

5. Describe the use of prosthetics for patients with amputations associated with burn injuries.

Rehabilitation of a patient with burns involves programs that focus on restoring functions compromised by the burn injury.1 Treatment strategies used by therapists address five important goals:

1. Improve or promote wound healing by reducing wound infection

2. Prevent or reduce deformity

3. Increase mobility and strength to achieve maximal function

4. Reduce effects of hypertrophic scarring

The rehabilitation plan for patients with burns centers on wound care, positioning, range-of-motion (ROM) exercises, splinting, strengthening exercises, endurance and functional exercises, gait training, and scar control. Burn care emphasizes the need for a comprehensive team approach to achieve maximal clinical results.1,2

Burn injury

Each year in the United States, 450,000 to 500,000 individuals sustain and seek medical care for burn injuries and an estimated 3500 of these injuries result in death.3 Estimates are that burn injuries result in approximately 45,000 hospitalizations per year.3 The American Burn Association has outlined criteria for determining the severity of burn injury, which include cause of the injury, burn depth, total body surface area (TBSA) burned, location of the burn, and patient age.4,5 A burn injury of any given size is more severe for patients who are very young or very old. The deeper the injury, the more serious the burn. Involvement of the face, eyes, ears, perineum, hands, and feet make the injury more critical. Associated trauma, smoke inhalation injury, and poor preinjury health status are factors that increase severity of the injury.6 An appropriate understanding of the nature of burn injury and the location and depth of the burn wound is important in understanding and anticipating the possible problems a patient may face during rehabilitation.

Causes of Burns

Types of burn injury include flame, scald, flash (radiant heat explosions), contact, chemical, electrical, and other (e.g., irradiation, radioactivity) burns.7 Scald and flame injuries are common causes of burn injury. Preschool-aged children are at the highest risk for suffering scald injuries.8–10 Flame burns are generally the leading cause of burn injury in other age groups.8,11 Chemical and electrical burns present differently than other burn injuries. Burns resulting from chemical agents require identification of the causative agent so that proper neutralization of the chemical can take place. Assessment of the depth of chemical burns is difficult at first, but these wounds are predictably deep.12 An electrical injury may have areas of significant surface burn; however, these areas are often the result of associated flash burns. Small, deep wounds where the current enters or exits the body are more typical.13 The major complication with rehabilitative consequence of electrical injury is musculoskeletal necrosis, which frequently results in the need for amputation.14,15

Burn Depth

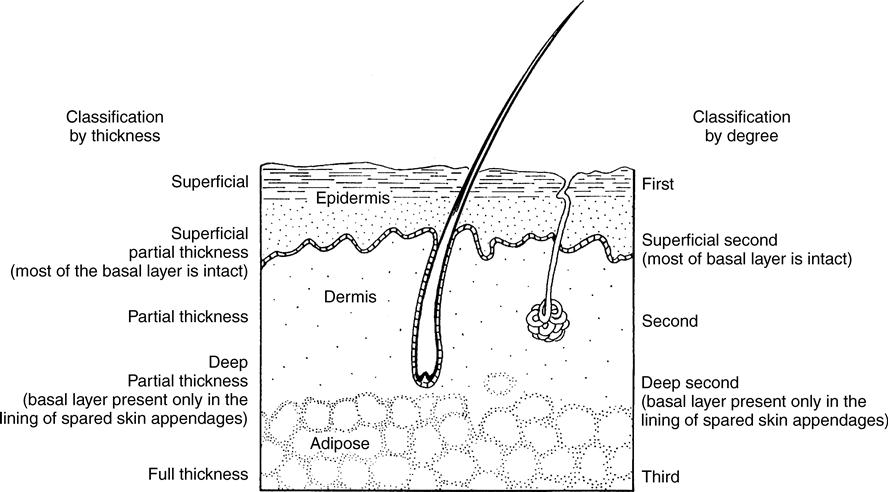

Thomsen16 has studied Indian writings dating back to approximately 600 BC that describe four levels or degrees of burn depth and declare that deep burns heal slowly and with scarring.16 There are two methods to describe burn depth: by degree (first, second, or third degree) or thickness (superficial, partial thickness, and full thickness).17 The thickness terminology is more commonly used in clinical practice. A superficial injury corresponds to a first-degree injury, a partial thickness to a second-degree injury, and a full thickness to a third-degree injury (Figure 15-1).

Clinical characteristics associated with the injury thickness are helpful in identification of the depth of burn.17 Superficial (first degree) injuries involve only the epidermis. They are often painful, erythematous, and mildly edematous. Superficial burn injuries usually heal in 3 to 7 days and they rarely result in scarring. Superficial partial-thickness burns (superficial second degree) compromise the epidermis and upper dermis. These burns are very painful, very red, and often have blisters or weeping wounds. Superficial partial-thickness burns usually heal in 14 to 21 days and rarely develop scar. In deep partial-thickness burns (deep second degree), deeper layers of the dermis are damaged. The wound may or may not be painful, it may be cherry red or pale, and the skin is still pliable. Deep partial-thickness burns require more than 21 days to heal spontaneously and will scar. In full-thickness burns (third degree) all layers of the skin are destroyed. The wound generally has a tan or brown appearance and exhibits a leathery texture. Full-thickness wounds are painless and need several weeks to heal without surgical intervention. Deep partial-thickness burns are often managed by skin grafting; full-thickness injuries require skin grafting. A deeper burn generally correlates with an increased severity of injury.

Surgical Management of Burns

Small burn wounds may be excised and primarily closed; however, most burn wounds require excision of the burn followed by coverage of the site with a skin graft.18 Excision of the burn wound is ordinarily performed tangentially; that is, thin layers of the burn are removed until viable tissue is reached.19 Autografts (split-thickness grafts) are harvested from undamaged areas of the body for coverage of the excised wound.19 Skin grafts placed on tangentially excised wounds demonstrate good long-term functional results.20 Full-thickness skin grafts can also be used. Interestingly, split-thickness grafts scar more than full-thickness grafts.20

Progress has been made in the use of skin substitutes and cultured skin for the coverage of the excised burn.21–23 Areas treated in this fashion tend to be fragile and susceptible to breakdown.24 Wounds treated with cultured epithelium do not aggressively scar; however, little information is available about the rehabilitative ramifications of this treatment approach.25

Burn Size

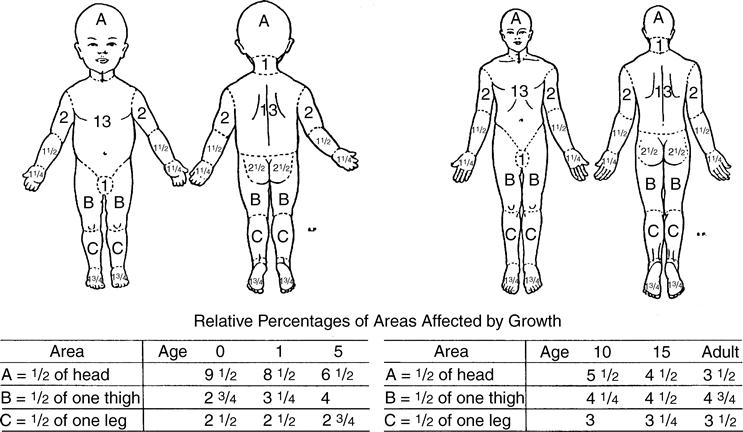

Burn wound size is reported as a percentage of the TBSA that is injured. Lund and Browder26 describe a method for estimating percent TBSA. Variations in body part ratios during development and diversified proportions of individual anatomical parts are considered in the estimation (Figure 15-2). The “rule of nines” is another technique for estimating surface area by dividing the body into 11 different areas equal to 9% each; the genitalia make up the remaining 1% of the total 100% estimate.27 A burn injury increases in severity as the percentage of TBSA burn increases. Large burns usually require longer convalescence, which in turn increases the rehabilitative needs of the patient.

Location of the Burn

Burns of the face, perineum, hands, and feet create special problems.6 Burns of the face are distressing because there may be cosmetic disfigurement, visual impairment, or compromised nutrition (intake of food). Injuries of the face are often accompanied by inhalation injuries. Hands and feet have broad functional importance that can be substantially compromised after burn injury. Severity of injury is significantly magnified as the total surface area of the hand or foot encompassed by the burn increases. Any burn that crosses a joint increases the risk for functional compromise and creates challenges in rehabilitation.

Wound care

The time it takes to heal a burn wound is directly related to depth of the injury. The more superficial a wound, the faster it heals. Surgical intervention, such as skin grafting, is often used to reduce healing time for deep wounds. Wound infection can significantly delay healing and lead to increased scar formation.28

Topical Agents and Wound Dressing

The outermost layer of epidermis (stratum corneum) in intact skin is too dry to support microbial growth and serves as an effective barrier to microbial penetration. As a result, skin infections seldom occur unless the skin is opened.29 Because this protective barrier is compromised or destroyed in burn injury, the risk for infection is greatly increased. Personal protective equipment, particularly gloves, gowns, and masks, must be worn when caring for patients with burn wounds.30 Topical agents may be applied to these open wounds after each cleansing and debridement to prevent or manage infections. Topical agents are particularly important for ischemic wounds in which systemic delivery of natural substrates to fight infection is compromised.29,31 A well-applied dressing minimizes discomfort and allows mobility.

Mild lotions help relieve dryness and itching in maturing healed wounds.29 The use of moisturizers helps prevent healed wounds from cracking or splitting. Because alcohol is a desiccant to the skin and exacerbates dryness, lotions that contain alcohol should be avoided. Fragrance-free moisturizers are recommended; most hypersensitivity reactions are triggered by perfumes. Moisturizers can also be beneficial when applying a splint, orthotic, or prosthetic device to a patient with healed burns or scar because they help protect the skin from desiccation and shear.

Rehabilitative personnel often take an active role in the wound care of a patient with burns. Involvement in wound care provides a better understanding of the reasons for discomfort. Familiarity with wound care procedures is often necessary for outpatient therapy sessions.32,33 Adjustments in the treatment plan are often necessary as the wound heals and tolerance of certain rehabilitative procedures changes. Consideration of the effects of pressure, shear, and friction on a healing wound or newly healed, fragile skin is especially important when splints, orthotics, prosthetics, or other external devices are being used.

Psychology of burn injury

An acute burn injury creates emotional distress. Treatment of the burns is often traumatic as well; stress and anxiety continue during the period of recovery. The psychological consequences of burn trauma in the adult include depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, despair, fear, anxiety, and survivor’s guilt.34–37 Children often feel guilt and manifest loss of interest in play, unpredictable sadness, avoidance, and regression.38–40

Psychological adaptation in early phases after burn injury includes denial (often manifest by a feeling of calmness), and concern about prognosis, pain, personal issues, and dependence on medical staff (depression).39,41 Individuals who become actively involved in the process of rehabilitation and self-care often are more encouraged and optimistic about the future.38,41

Rehabilitation professionals can facilitate psychological function and recovery of patients with burns in several ways. Encouraging independence by allowing individuals as much control over medical procedures as possible helps them focus on recovery and empowers them to a certain degree.41,42 Patients feel more comfortable with caregivers if they have the opportunity to get to know one another outside painful treatment settings.38,42 Support and understanding demonstrate a caring attitude. Tactful but honest answers to questions about prognosis, cosmesis, and functional outcome help establish trust.38 Ongoing education about the recovery process helps the patient develop realistic expectations about recovery.

Rehabilitation intervention

Early surgical intervention, availability of nutritional support, and pharmaceutical advances have improved survival after burn injury and the American Burn Association has reported a survival rate of 94.8% from 2000 to 2009.3 As a result of improvement in care, treatment, and survival of burned patients, more physical therapists will become responsible for treating these patients for a significant portion of their rehabilitation in settings other than a hospital burn center (e.g., outpatient clinics, community hospitals).

This improvement, in turn, has increased the emphasis on and need for rehabilitation of patients with burns. Physical therapists and occupational therapists are important members of the burn care team.

After examination and evaluation, the team establishes goals and designs and implements an appropriate plan of care. Important rehabilitation goals for patients with burns might include the following as put forward in The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice: (1) wound and soft tissue healing is enhanced; (2) risk of infection and complications is reduced; (3) risk of secondary impairments is reduced; (4) maximal ROM is achieved; (5) preinjury level of cardiovascular endurance is restored; (6) good to normal strength is achieved; (7) independent ambulation is achieved; (8) independent function in activities of daily living (ADLs) is increased; (9) scar formation is minimized; (10) patient, family, and caregivers understanding of expectations and goals and outcomes is increased; (11) aerobic capacity is increased; and (12) self-management of symptoms is improved.43

Burn rehabilitation interventions emphasize patient independence through achievement of maximal functional recovery.44

Wound Healing and Scar Formation

Unhealed burn wounds can create challenges during rehabilitation. Most problems in burn rehabilitation are caused by the ceaseless contraction and hypertrophy of immature burn scars.45 Scar contracture can lead to visible cosmetic deformity of involved body parts, particularly of the face and hands. Functional limitations are common when the scar crosses a joint. The contraction of scar has been classically associated with a type of fibroblast called myofibroblasts, which have contractile properties.46–48

Burn wound healing encompasses three phases: the inflammatory phase, the proliferative phase, and the maturation, or remodeling, phase.49 The inflammatory phase is characterized by the formation of new blood vessels, an initial defense against infection, and migration of fibroblast and epithelial cells into the injured area. Treatment focuses on proper wound care to encourage vascular regrowth and retard contamination of the site. The proliferative phase is marked by continued revascularization, rebuilding, and strengthening of the wound site as a result of vigorous synthesis of collagen by fibroblasts, and reepithelialization.50 Treatment is directed toward promoting epithelialization and encouraging proper alignment of newly deposited collagen fibers. During the maturation phase, the wound site is further strengthened by protracted deposition of collagen fibers by active fibroblasts. Treatment during maturation stresses lengthening the scar, reconditioning the patient, and returning the patient to preburn functional levels. Activity and rehabilitation interventions aimed at opposing wound and scar tightness and education about the process of recovery are critical in all phases of healing.

While fibroblasts deposit collagen during the proliferative phase, macrophages and endothelial cells release enzymes that degrade collagen. The severity of scar formation is determined by the balance between collagen synthesis and lysis: the more that collagen deposition exceeds its breakdown, the more likely a significant scar will form.51,52 A hypertrophic scar is raised above the normal surface of skin (Figure 15-3).53–55 A keloid occurs when the scar extends beyond the initial boundaries of the wound.53–55

An immature scar is raised, red, leathery, and stiff. As the scar matures, it becomes pale, relatively soft and flattened, and more yielding.56–58 The process of scar maturation requires 6 to 18 months after wound closure; scars actively contract during maturation.56,57,59 Contraction is most vigorous in the early months of maturation but continues throughout this period of remodeling.

Superficial and partial-thickness burns usually do not scar; full-thickness burns almost always do. Full-thickness wounds closed by a skin graft scar significantly less than a similar wound allowed to heal spontaneously. Very dark-skinned or very fair-skinned individuals and those with familial history of susceptibility to scarring are more likely to form hypertrophic scar.60–63 The larger the burn, the greater the likelihood of scar formation.62–64 A contracture occurs when a portion or distortion of the shortening scar becomes fixed or semifixed.65 The axilla, elbow, hand knee, face, and neck are common and most problematic sites of scar contracture formation.61,63,65 One of the most important goals of burn rehabilitation is to prevent, counteract, and minimize the adverse effects of scar contraction.65

Operative Scar Management

Surgery is used to correct scar contractures that have created specific functional deficits or deformities.66 Surgical techniques used to release scar contracture include split-thickness or full-thickness skin grafts, skin flaps, Z-plasties, and tissue expansion.66,67 Most surgeries are deferred until at least 6 months after the burn or until the scar is sufficiently mature.66,67 Although surgery alleviates contracture-related problems, it also creates a new wound with its own subsequent scar maturation process. Rehabilitation is necessary after a majority of reconstructive surgeries to again avert the affects of contraction.

Nonoperative Scar Management

The nonoperative control of hypertrophic scarring most commonly involves pressure therapy and the application of silicone gel sheeting. The use of continuous pressure for the treatment of burn scars was described in 1971.68 Pressure has also been shown to relieve other aggravating discomforts of the healing burn wound, such as itching and blistering.69–72 ROM is not significantly impeded with pressure garments despite the restriction felt by patients (particularly initially) when fit with pressure garments.73

Pressure therapy is indicated when healing requires more than 14 days or if skin grafting has been performed. There are several strategies to assess burn scar condition. The Vancouver Scar Scale developed by Sullivan and colleagues describes severity of the scar by rating pigmentation, vascularity, pliability, and height of the scar tissue (Box 15-1).74

Early pressure therapy is used to control edema in a wound even if there is no ensuing scar formation. Some of the most common elastic materials used on newly healing, still fragile wounds include elastic bandages, Coban self-adherent wrap (3M Medical, St. Paul, Minn.), or elasticized cotton tubular bandages such as Tubigrip (SePro Healthcare, Inc., Montgomeryville, Pa.).75–77 These materials are useful while the patient is waiting for the arrival of custom-fit, antiburn scar supports.75–77

Individuals with scars are commonly fitted with custom-fit pressure garments for the duration of the maturation phase of healing. Custom-fit, antiburn scar supports are available from manufacturers such as Bio-Concepts (Phoenix, Ariz.), Barton-Carey Medical Products (Perrysburg, Ohio), Gottfried Medical (Toledo, Ohio), and Medical Z (San Antonio, Texas). Although the measuring procedure varies by manufacturer, most require measurements approximately every 1 to 1.5 inches along each extremity, with special guidelines for the torso, face, and hands. Burn scar supports can be fabricated to fit almost any body part, including the face, torso, upper extremity, hand, and lower extremity. Some burn centers fabricate rigid or semirigid face masks (essentially orthotics) in an attempt to gain a better match with facial contours.78

Pressure garments and devices are worn through the entire process of scar maturation, to be discontinued only when the scar has completely matured.1 Fit of pressure garments is regularly reassessed to ensure the desired therapeutic effect. Regular follow-up provides an opportunity for the patient to discuss other ongoing rehabilitative problems associated with the burn.

Silicone gel sheets or pads can be put right on a maturing scar. Silicone gel sheeting is generally applied over small areas or on scar where it is otherwise difficult to provide sufficient pressure. The mechanism of action for the effect of silicone gel on scar is not known.79,80

Burn rehabilitation interventions

Many different types of rehabilitation interventions are appropriate in the care of patients with burns. Although many interventions are briefly described in the following section, the emphasis is on the use of splints, orthoses, and prosthetic devices.

Therapeutic Exercise

Exercise helps minimize outcomes of burn injury and burn scar formation by improving mobility and function.81 As important and effective as exercise is in burn rehabilitation, some individuals may be reluctant to exercise (and some therapists may be reluctant to encourage them) because of the anticipation of increased pain or anxiety about damaging newly healing tissue. Exercise programs for patients with burns are principally directed at the prevention of burn scar contractures and the side effects of inactivity and disuse. Additional consequences of immobilization in these patients can include progressive contracture of the joint capsule and pericapsular structures, atrophy and contracture of muscle, deleterious effects on articular cartilage, and possible decrease in bone strength. Exercise is a significant health promotion and disability prevention component in the rehabilitation of patients with burns.

Assessment of location and depth of burn injury identifies those areas most at risk of burn scar contracture. This assessment also guides design of an exercise program to improve mobility, strength, and functional status. Past and present medical conditions influence rehabilitative expectations; a previous orthopedic injury may have already reduced ROM of a particular joint whereas a concomitant inhalation injury may limit exercise tolerance.

Active Exercise

After a burn, exercise may be difficult because of edema, pain (particularly over areas of partial-thickness burns), the loss of skin elasticity in the burned tissue, and wound contraction.44,82 Early on, edema is a major contributor to stiffness of joints; active exercise is valuable in reducing the edema.32,83 Positioning and compressive wraps or devices are used for edema control in addition to exercise. Pain tolerance varies widely among individuals. The therapist is challenged to help the patient understand the importance of activity despite the pain involved. Many individuals have relief of their pain and stiffness after exercise periods, which may encourage them to participate in the subsequent therapy sessions. Persons who understand the advantages of exercise may be asked to confer with, and encourage, newly injured individuals or those having difficulty with their exercises.

General stiffness from the loss of skin elasticity and wound contracture is a short-term problem but often persists during the process of scar maturation, especially for those who form a hypertrophic scar. Exercise targeting those areas most vulnerable to scar formation identified in the initial evaluation must begin as early as possible after admission.44,84 Early presentation of an exercise routine aids edema control, relieves stiffness, and prevents loss of strength and ROM. The early introduction of active exercise reinforces the importance of exercise to the individual, who will incorporate daily exercise as a important contributor to overall recovery. Because of the wide scope of benefits derived from active exercises, they are the preferred form of ROM exercises for patients with burns. A survey of physical and occupational therapists, 96% reported instituting active ROM exercises within 24 hours of acute burn center admission.85

Patients are also encouraged to perform independent activities of daily living.44,83 Self-reliance is important after burn injury, and independence can increase the patient’s self-confidence.44,83 It is likely that the more patients can do, particularly in directing their exercise programs, the more compliant they will become.84 Independence in an exercise program is therefore an important goal for those recovering from burn injury.

The primary goals of active exercise for patients with acute burns are opposition of tissue contraction and strengthening. For an individual with a burn crossing the antecubital fossa and weakness of the biceps brachii, exercise is focused on preservation of elbow-extension ROM and functional strength of the muscle. If a patient with a burn encompassing the lower leg and ankle also has weakness and atrophy of the triceps surae, appropriate strengthening exercises may be performed, but certainly not at the sacrifice of active ankle ROM.

Conditioning exercises can be incorporated to improve the cardiovascular status of the patient.86 Occupation-specific training programs may be a part of the long-term rehabilitation plan as patients plan to return to their jobs. This type of activity may be directed at one or a few specific functions or may incorporate a traditional work-hardening program.

Gait Training

The functional nature of ambulation makes it an important exercise for burned lower extremities.87 Ambulation assists with edema control, ROM, and strengthening in all lower extremity joints. Ambulation also helps with the function of other physiological systems such as the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal systems. Individuals with lower extremity burns exhibit gait deviations related to compromised joint function, such as incomplete hip and knee flexion in initial swing and incomplete knee extension in terminal swing. Initial contact may be made with the entire foot (foot flat) instead of the heel, and loading response may be compromised by lack of plantar flexion ROM or an unwillingness to perform the controlled knee flexion necessary for shock absorption. Excessive knee flexion in midstance, poor or absent heel-off and weight shift in terminal stance, and inadequate knee flexion in preswing are often present.33 Differences in individual gait deviations in gait phases are generally based on variations in the location, size, and depth of the burn injury and levels of pain. Any gait deviation caused by the burn may accentuate the need for vigilant gait training of a patient with burns who also has a lower extremity prosthesis. Exercise is an important adjunct to gait training because it can address specific movement limitations of the lower limbs.

Passive Exercise and Stretching

Passive exercise is included in therapy regimens when patients are unable to move on their own or cannot actively complete normal ROM. Passive ROM and slow, gentle stretching exercises that elongate healing soft tissues are used to preserve and improve joint ROM.88 Eighty-four percent of physical and occupational therapists reported initiating passive ROM stretching exercises within the first 24 hours after burn center admission.85 Blanching of the scar indicates an appropriate amount of stretch. Although the scar should be stretched to the point of tolerance, joint movement should not be forced because of possible tissue damage and the potential for heterotopic ossification.89–91

Positioning or splints are used after a stretching session to maintain the achieved ROM. Suitable stretching positions must also consider scars that cross multiple joints and therefore affect a broad kinematic chain.

Most of the exercise equipment typically found in rehabilitation settings is appropriate for patients with burns. The therapist must decide when certain equipment will be most beneficial and incorporate the use of this resource into the plan of care. The use of latex rubber tubing for strengthening and overhead reciprocal pulleys for increasing ROM are a few examples of simple equipment that have been described in the literature.92–94 Bicycle ergometers for either the upper or lower extremities assist with motion, provide resistance, and allow for some cardiovascular workout.

Physical Agents

Because of the variety of treatment goals important for burn rehabilitation, many different types of modalities may be used for appropriate intervention. Hydrotherapy, functional electrical stimulation (neuromuscular electrical stimulation), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, ultrasound, continuous passive motion (CPM), and paraffin are physical agents that have been reported to be used in burn care. Hydrotherapy is most often used for wound care but may also be used for dressing removal and exercise.95 If hydrotherapy is chosen as a thermal modality, precautions similar to those used for any open wound care are necessary to reduce the chance of cross-contamination.

Functional electrical stimulation has been successfully used to treat hands that have responded poorly to typical treatment.96 Burn pain has been altered by transcutaneous electrical stimulation in some cases.97 Ultrasound has been used to treat pain and ROM impairments in patients with burns; however, the efficacy of ultrasound in either decreasing pain or improving motion is still a matter of some debate.98–100 Successful use of CPM has been specifically reported for hand burns and lower extremity burns at the knee.101 The gentle heat provided by paraffin, as well as the potential skin softening from the mineral oil in the paraffin, may be reasons for the use of this modality in burn care.102

Healing skin and recently healed skin are often very sensitive. Scar tissue has varying levels of sensory deficit.103,104 Accordingly, heat, cold, coupling agents, and electrode adhesives may lead to skin breakdown. Caution must be exercised when applying any modality; thorough pretreatment and posttreatment inspection of the site is warranted.

Positioning

Positioning is an important component of any burn rehabilitation program. Positioning is used for acute burn and postsurgical edema control and to prevent or treat scar contractures.105 The initial burn therapy evaluation identifies sites at risk for contracture formation; appropriate counteractive positions become part of the therapy plan. Contracture prevention is more successful when a program of positioning and activity is instituted as soon after burn as possible.44,63

Postexercise positioning extends the effects of activity; positioning is also fundamental for individuals who cannot move or exercise. Manufactured positioning devices, such as arm boards that attach to the side of the bed, are available to assist in proper positioning of extremities. Positioning need not be expensive or require intricate equipment. Avoiding the use of a pillow behind the head is a simple way of decreasing neck flexion and facilitating a neutral alignment of the head and neck. A pillow or several folded blankets placed under the arms can effectively elevate the burned limb while keeping the elbows extended and supporting the hands. At least some horizontal flexion of the shoulders is indicated to minimize prolonged stretch of the brachial plexus.106,107 A washcloth, towel, or gauze roll placed in the palm helps hold the hand in a functional position. Pillows, high-top tennis shoes, towels, blankets, and foot boards help position the foot with a neutral ankle.44 Positions of choice for a patient with burns are shown in Box 15-2 (see next page).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree