Chapter 153 Soft Tissue Tumors of the Knee

Clinical Features

Patients with tumors may have painless masses but, especially with intra-articular neoplasms, may also complain of joint pain, loss of motion, locking, or effusion, further complicating the clinical picture. In a retrospective review of patients with benign or malignant bone or soft tissue tumors about the knee, Muscolo and colleagues26 found that 3.7% of these patients had previously undergone an invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedure for a presumptive diagnosis of a sports-related injury, such as meniscal lesions, patellofemoral subluxation, or anterior cruciate ligament rupture. None of the patients in this series had undergone initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These patients were reexamined, including evaluation by MRI, because of lack of improvement after the initial procedure. Over half of these patients ultimately underwent a more extensive oncologic procedure than that which would have been offered on the basis of the original studies as a result of soft tissue contamination during the initial procedure or progression of the tumor because of delay in diagnosis. Lewis and Reilly,22 in a review of tumors originally misdiagnosed as sports-related injuries, found that half of these tumors were soft tissue neoplasms, with synovial sarcoma being the most frequent diagnosis.

Soft tissue tumors about the knee may arise from the surrounding soft tissue and have an incidence similar to that of benign and sarcomatous masses seen at other anatomic locations. Benign lesions include lipomas, extra-abdominal desmoids, and peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Malignant lesions include synovial sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, pleomorphic sarcoma (malignant fibrous histiocytoma [MFH]), lymphoma, and soft tissue metastases from remote carcinoma. Soft tissue masses may also originate from within the intra-articular space and include pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), primary synovial chondromatosis, and lipomatous lesions. Cystic lesions, such as Baker’s cysts, meniscal cysts, and proximal tibiofibular cysts, may also be manifested as juxta-articular masses. Rarely, non-neoplastic entities such as calcific tendinitis, hemorrhagic bursitis of the infrapatellar or prepatellar bursae,33 or gouty tophus3 have been described as mimicking soft tissue masses of the knee.

Evaluation

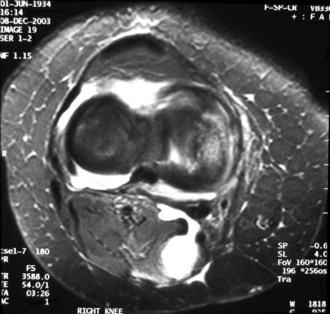

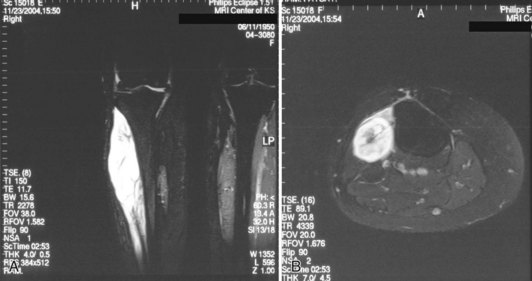

MRI can help delineate the location and composition of the lesion further and can assist in the evaluation of lesions whose diagnosis cannot be determined from physical examination and other radiographic modalities (Fig. 153-1). MRI can confirm the cystic nature of Baker’s and meniscal cysts, as well as identify any associated intra-articular pathology. These cysts are typically homogeneous, with high signal on T2-weighted images. However, there may be some heterogeneity because of hemorrhage or debris. If the image is not characteristic, especially if there is no associated intra-articular pathology, the diagnosis of meniscal or Baker’s cysts should be made with caution.25 MRI may confirm the cartilaginous nature of synovial chondromatosis, which may or may not be mineralized and detected on plain films. MRI can also indicate the presence of hemosiderin within PVNS, as well the extent of intra- or extra-articular involvement. Lipomas are easily detected with MRI; they should have the same appearance as subcutaneous tissue, especially on fat-suppressed sequences. Most other soft tissue masses do not have a characteristic appearance on MRI. Enhancement of the lesion with gadolinium helps confirm the neoplastic nature of the lesion. Heterogeneity, as well as involvement of adjacent tissue, is suggestive but not diagnostic of malignancy.

Differential Diagnosis

Cystic Lesions

Cystic lesions adjacent to the knee may reflect involvement of the bursae related to the patella, pes anserinus, iliotibial band, or collateral ligaments.24 However, symptomatic cysts are more commonly found in the popliteal space (Baker’s cyst), at the joint line (meniscal cysts), or within the joint (intra-articular ganglion cysts). The first two are typically associated with intra-articular pathology.

Baker’s cysts typically arise in adults between the tendons of the semimembranosus and medial head of the gastrocnemius (Fig. 153-2). The prevalence of Baker’s cysts increases with age. These cysts are filled with joint fluid and reflect intra-articular pathology such as meniscal tears or degenerative joint disease. In patients with Baker’s cysts, 82% were found on MRI to have an associated meniscal tear, most commonly medial, and 13% to have a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL); some patients had a combination of ACL and meniscal tears, with 7% having tears of the ACL and both menisci.16 Adult patients may complain of aching and a feeling of fullness in the posterior aspect of the knee, as well as symptoms from the associated knee pathology.9 Rupture of the cysts can cause acute pain and swelling in the posterior aspect of the knee and leg. Treatment of cysts in adults is targeted at the underlying joint pathology. In a follow-up study of patients treated arthroscopically for intra-articular lesions without addressing the popliteal cysts, chondral lesions were the most relevant prognostic factor for persistence of the cyst.28 If the cyst persists and remains symptomatic, open excision, with suturing or cauterization of the stalk emanating from the joint, may be undertaken.

Meniscal cysts are located more medially or laterally than a popliteal cyst. They are typically, but not exclusively, associated with a meniscal tear. The diagnosis is more straightforward if the lesion is homogeneous on MRI. The lesions may be lobulated and septate.32 Treatment is aimed at the underlying meniscal pathology.

Intra-articular ganglion cysts are not associated with other intra-articular pathology. They may be found in the infrapatellar fat pad, adjacent to the anterior cruciate ligament, or adjacent to the posterior cruciate ligament, with the latter being the most common in the series by Kim and associates.21 The clinical findings of intra-articular ganglion cysts vary according to the location of the cyst. Lesions in the infrapatellar fat pad may be characterized by a palpable mass. Patients with cysts in the intercondylar notch may have pain, especially when they are in a squatting position. Patients may also have symptoms of knee locking. MRI is typically diagnostic in these cases, with the cysts usually demonstrating homogeneous high signal on T2-weighted images. Symptomatic cysts may be removed via an open procedure or arthroscopically.

In a review of 654 MRI scans of the knee, the prevalence of proximal tibiofibular cysts was found to be 0.76%.20 Only half of these cysts were symptomatic. When proximal tibiofibular joint cysts are symptomatic, an anterior soft tissue mass is typically present (Fig. 153-3). With time, these cysts may lead to compromise of peroneal nerve function. Removal of these cysts may require dissection of the cyst from the epineurium10 but can lead to recovery of at least some degree of nerve function.

Intra-articular Pathology

PVNS is a condition of unknown cause, with both inflammatory and neoplastic causes suggested. Its propensity for local recurrence, including recurrence in the subcutaneous tissue adjacent to arthroscopy portals,23 as well as its monoclonality, may point toward a neoplastic origin. In addition, a variety of balanced chromosomal translocations, primarily involving chromosome 1p13, have been identified. Cupp and coworkers8 have identified colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) as the gene at the typical 1p13 breakpoint. Although only a minority of cells evaluated from PVNS resection specimens contained this translocation, they hypothesized that the aberrant CSG1 expression results in the accumulation of non-neoplastic macrophages and monocytes, forming the tumor mass.

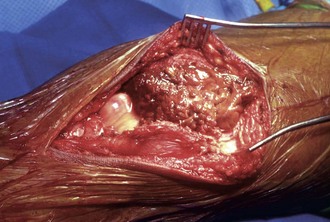

PVNS can affect any joint, with involvement of the knee being the most frequent. It can also extend into and involve the surrounding soft tissues. PVNS occurs in a localized (nodular) or diffuse form (Fig. 153-4), with the latter being more common. Patients typically have recurrent knee swelling (hemarthrosis) and pain; they may also complain of locking and feelings of instability. Because of these nonspecific symptoms, establishing the diagnosis can be difficult, with an average delay of longer than 4 years from the onset of symptoms.15 Plain films do not demonstrate any mineralized lesions, which may help distinguish PVNS from synovial chondromatosis, although the latter is not always mineralized. MRI in PVNS typically demonstrates a knee effusion as well as a single intra-articular mass in the localized form or, in the diffuse form, multiple intra-articular masses (Fig. 153-5); the latter may also demonstrate extension into the adjacent extra-articular soft tissues. These masses are low signal on T1- and T2-weighted images because of the presence of hemosiderin.32 The presence of hemosiderin is also responsible for the so-called blooming artifact. The appearance of hemosiderin is considered diagnostic for PVNS. Erosion into adjacent bone may be seen on plain films and MRI scans, although bone involvement is less common in the knee than in other joints, such as the hip. The presence of bone involvement is thought to be caused by the presence of a narrow joint space (Fig. 153-6).4 However, Uchibori and colleagues35 have found increased production of matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 9, thus suggesting an additional mechanism for bone and cartilage loss in PVNS. More recently, Geldyyev and associates18 found significantly elevated expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), a key modulator of osteoclast differentiation and activation, in PVNS tissue, compared with synovial tissue of patients with osteoarthritis with RANKL not being expressed in normal synovial tissue. Although there were no differences demonstrated in RANKL activity between PVNS lesions that demonstrated adjacent bony erosion versus those that did not, it was hypothesized that this increased expression of proteins involved in bone loss might facilitate the intraosseous extension of PVNS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree