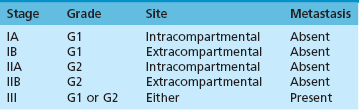

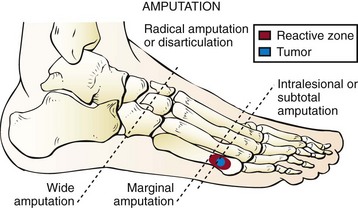

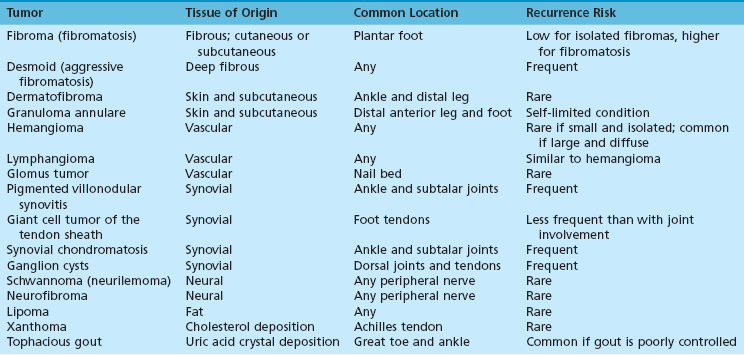

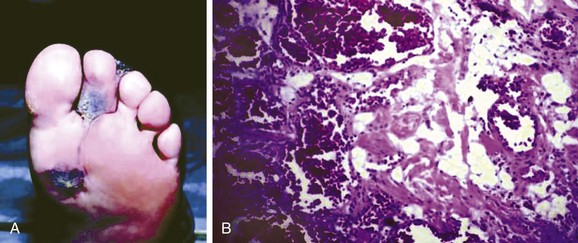

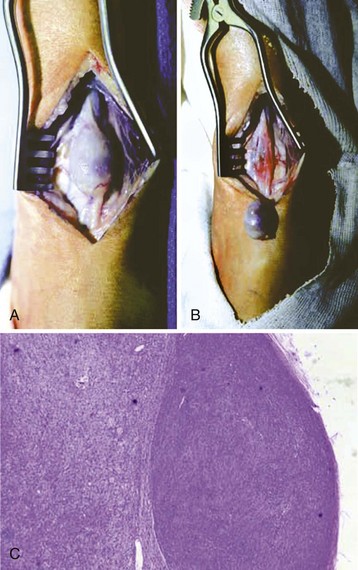

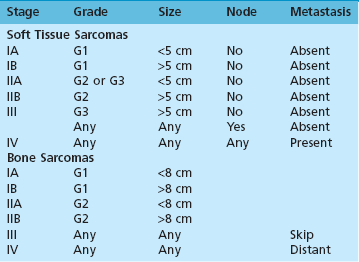

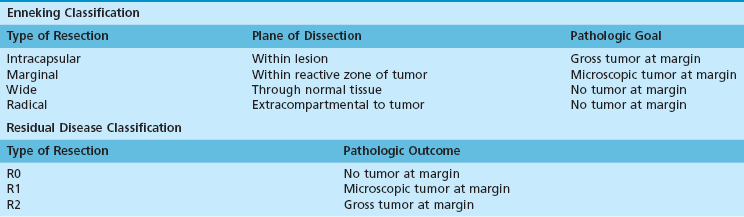

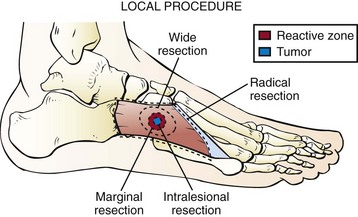

Chapter 18 As with any history, the chief complaint consists of a symptom and duration. Unlike many foot pathologies, it is common for tumor patients to present with a symptom other than pain. Many note a painless mass or discomfort with footwear because of rubbing of the mass. It is important to note that pain, or lack thereof, is a poor indicator of malignancy. Many benign entities are very painful, and many if not most sarcomas fail to cause pain until they reach a large size. The character of pain is often more useful in developing a differential diagnosis. Night pain is classically associated with tumors and infection. However, a study of presenting symptoms in patients with bone sarcomas found that most reported a history of strain or minor trauma.188 Burning pain associated with a mass suggests nerve compression or entrapment by the mass or direct nerve involvement by a tumor such as a schwannoma. Weight-bearing pain associated with a bone lesion should alert the clinician to the possibility of pathologic fracture. Similar to pain, the duration of symptoms cannot distinguish benign from malignant entities. Masses present for many years without change in size are almost always benign. However, rapid growth can frequently occur in benign lesions, and slow, persistent growth is common in many sarcomas. Thus duration of the mass should be interpreted in light of the rate of growth and other symptoms. Table 18-1 reviews history of present illness elements, which should be addressed by the surgeon, and their association with particular pathologies. In addition, the foot and ankle surgeon should also elicit past medical and surgical history, social history (especially smoking and occupational exposures), family history (especially cancer and genetic syndromes), and review of systems relevant to the tumor complaint. Table 18-1 Specific History Elements Useful in Foot and Ankle Tumor Evaluation Similar to history, physical examination provides critical insight for diagnosis of foot and ankle tumors. Inspection permits estimation of tumor size, alignment of the foot and ankle, discoloration, and quality of the skin and soft tissue envelope. Palpation indicates if the tumor is mobile or fixed to bone, firm or soft, warm or cold, and tender or nontender. Neurologic and vascular examination determines if the tumor is compromising either of these vital functions to the foot. Joint motion and stability is also assessed to determine if the tumor involves or adversely affects nearby joints. Physical examination tests specific to masses include auscultation and transillumination (Table 18-2). Auscultation is classically performed with a stethoscope; however, many foot and ankle surgeons routinely use ultrasound Doppler for evaluation of vascular insufficiency. Either modality can be used to identify a bruit associated with vascular malformation. Transillumination indicates that a lesion is at least partially cystic. Lymph node examination of the ipsilateral popliteal fossa and groin should also be performed. Lymphatic spread is relatively uncommon in primary malignancies of the foot and ankle, but there are specific tumors in which it is more common. Table 18-2 Physical Examination Elements Useful in Foot and Ankle Tumor Evaluation Plain radiographs are often more important in developing a differential diagnosis of bone tumors than MRI and computed tomography (CT). Table 18-3 summarizes characteristics of the images that should be assessed for all bone tumors and their significance with respect to differential diagnosis. Some key points to analyze in each set of images are the location, size, matrix, border, periosteal response, and soft tissue involvement of the lesion.127 In addition to developing a specific radiographic differential diagnosis, the surgeon should develop a general concept of what constitutes a benign-appearing lesion as opposed to an aggressive lesion. Large size, periosteal response, cortical destruction, and associated soft tissue masses are all features that should alert the physician to a more aggressive lesion. Small size, sclerotic borders, and lack of soft tissue mass suggest a more indolent process. Table 18-3 Radiographic Features of Bone Tumors Plain radiographs are also useful in the evaluation of soft tissue masses. They can identify or exclude underlying bone and joint abnormalities, such as osteoarthritis in the case of degenerative cysts. Soft tissue masses are often visible on radiographs, and their radiodensity may provide insight into the diagnosis. For instance, the fat of a lipoma is less radiodense than the surrounding tissues. Finally, there are some pathognomonic or at least characteristic radiographic findings associated with particular lesions. A classic example is the phlebolith, the small discrete area of soft tissue calcification seen in association with hemangiomas. Characteristic imaging findings of some specific lesions are summarized Table 18-4. Table 18-4 Characteristic Imaging Findings of Specific Pathologies The excellent bone detail and cross-sectional imaging provided by CT can be invaluable in select cases. Advantages of CT over MRI include better bone resolution, faster image acquisition times, and lower costs. Fine cut (1 to 1.5-mm sections) CT scans can be very useful in defining the complex and irregularly shaped anatomy of the hindfoot. Cortically based lesions, such as osteoid osteoma, are often better visualized with CT than MRI. A study comparing the diagnostic accuracy of MRI versus CT for the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma found CT to be more accurate.86 The fast image acquisition times can be useful for patients, such as children, who cannot remain still for prolonged imaging. Fast acquisition and the ability to use metal instruments also facilitates CT-guided procedures, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA), that would be difficult with MRI. Finally, chest CT is routinely used in the staging of malignant foot and ankle lesions to identify pulmonary metastases. MRI is the imaging modality of choice for defining the local anatomy of soft tissue tumors and most bone tumors of the foot and ankle.192 Advantages of MRI over CT include better soft tissue resolution, multiplanar imaging, and avoidance of radiation exposure. Most oncologic surgeons recommend the use of intravenous contrast with MRI when evaluating tumors of the foot and ankle. Contrast enhancement helps to better identify the maximal extent of lesions and can help with determining the differential diagnosis. Some specific tumors have a unique MRI appearance or signal pattern.137 These are reviewed in Table 18-4. Although MRI is often very useful in the evaluation of foot and ankle tumors, the requesting surgeon should have a clear rationale for ordering this expensive test. Most asymptomatic, benign-appearing lesions can be monitored with history, physical examination, and radiographs. MRI is best used in symptomatic or aggressive-appearing lesions in which biopsy or surgical intervention is being contemplated. MRI is best understood as a planning rather than diagnostic tool. A newer nuclear medicine modality is positron emission tomography (PET). The most common tracer molecule used with PET is fludeoxyglucose (FDG), an analogue of glucose. FDG-PET identifies areas of increased glucose metabolism, such as tumors. It is a standard staging modality in the evaluation of melanoma122 and is being studied as a potentially more sensitive and specific alternative to bone scan for sarcomas.33 The purpose of cancer staging is multifactorial. Staging assists in guiding treatment by determining the extent of disease. Staging also provides caregivers and patients with prognostic information about morbidity and survival. In addition, accurate staging permits investigators from different centers to communicate effectively, thus facilitating research and improved treatment. The terms grade and stage are sometimes used inappropriately. Histologic grade is determined by pathologic analysis of tumor tissue. Grade is an important component of many staging systems, but these systems use other data, such as size and anatomic spread, in addition to grade. This section will focus on the staging of bone and soft tissue sarcomas of the foot and ankle. The reader should be aware that other malignancies, such as melanoma and carcinomas, have their own staging systems. The two major staging systems used for bone and soft tissue sarcomas in North America are the Enneking system58,59 and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)57 system (Tables 18-5 and 18-6). Table 18-6 American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging G1, grade 1; G2, grade 2; G3, grade 3; Skip (metastasis), metastasis within the same bone. The AJCC system uses the familiar tumor size–lymph nodes–metastasis (TNM) nomenclature used in the staging of most common cancers, such as breast and lung. The staging for bone and soft tissue sarcomas differ in the AJCC system. The AJCC system is used for reporting stage data to national and international registries and is favored by most major cancer centers in North America and beyond. AJCC uses four factors in defining soft tissue sarcoma stage: histologic grade, size, lymph node involvement, and metastasis. Previous editions of the system also used location, either superficial or below the fascia, to determine stage. Location remains an important clinical consideration, but it no longer influences staging. Lymph node involvement is rare among all bone sarcomas and most soft tissue sarcomas. The five soft tissue sarcomas with relatively frequent lymphatic spread are listed in Table 18-7. Although both the AJCC and Enneking systems have been shown to accurately predict survival in retrospective cohorts of sarcoma patients, the latter’s use is ever decreasing as orthopaedic oncologists further integrate into the multidisciplinary clinical oncology paradigm. The foot and ankle surgeon should be familiar with the tests commonly ordered in the staging process. Obtaining this information is not only useful to the patient but assists the practitioner in deciding what treatments to offer and what consultations to obtain. Common staging studies are listed in Table 18-8. One must also remember that staging should be repeated before surgery if neoadjuvant chemotherapy is given or if there is any other significant delay between the initial staging and surgery. Table 18-8 Imaging Studies Frequently Used in Sarcoma Staging CT, computed tomography; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. Biopsy is crucial for the effective diagnosis, staging, and treatment of foot and ankle tumors. The primary goal of biopsy is to obtain adequate tissue to establish a diagnosis without compromising the ability to perform a definitive resection if the tumor is found to be malignant. The first decision to be made is whether biopsy is necessary. Many of the most common foot “tumors” encountered by surgeons can be excised without biopsy if the history, physical examination, and imaging are classic for a benign diagnosis. A typical example is a ganglion cyst located over a joint that waxes and wanes in size and transilluminates on examination. Most foot masses are long-standing, small, superficial lesions that can be treated by the general foot and ankle surgeon without staging and biopsy. A sound general principle is that a biopsy should be performed if a malignant entity is included in the surgeon’s preoperative differential diagnosis. Any lesion that is rapidly changing in size, larger than 5 cm, or deep should raise concern for a potentially malignant process. It has been shown in multiple studies that sarcomas are best treated at specialized centers, and early referral should be considered for aggressive-appearing tumors.147 The second decision is what type of biopsy to perform. The general categories are needle and open biopsies. Needle biopsies are further subdivided into core needle biopsies and fine needle aspirations (FNA). Open biopsies are subdivided into incisional and excisional. Advantages and disadvantages of each are summarized in Table 18-9. Many needle biopsies are performed in an office setting or under image guidance in the radiology suite. If these procedures are to be performed by a radiologists or pathologist, the site of needle entry should be determined in conjunction with the surgeon, to avoid compromising future resection. A common misconception with open biopsies is the meaning of the term excisional biopsy. This refers to a biopsy technique in which the entire tumor is excised with a cuff of normal tissue (primary wide excision) for both diagnostic and definitive therapeutic effect.6 This is best performed by experienced tumor surgeons for small, superficial masses. This type of biopsy is rarely indicated because primary wide excision is often unnecessarily morbid for benign entities. Unfortunately, many practitioners inappropriately define unplanned excisions of malignancies as excisional biopsies. These “incidentaloma” procedures are usually done without appropriate staging studies, oncologic rationale, or surgical technique. Such procedures often complicate definitive resection of the tumor and compromise the care of the patient.145 Table 18-9 Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Biopsy Techniques Although biopsies are relatively small procedures, thorough planning and meticulous surgical technique are essential to obtain adequate tissue while avoiding contamination of uninvolved tissue planes with tumor cells. Open incisional biopsy is the standard technique for most bone foot and ankle bone tumors and many soft tissue tumors. Preoperative planning involves careful review of radiographs and cross-sectional imaging. The most aggressive-appearing portion of a tumor should be targeted because it is most likely to contain diagnostic tissue. For example, in a lesion with cystic and solid components, the solid portion should be sampled. The surgeon should confirm that appropriate equipment is available, such as a C-arm intensifier and trephines for bone lesions. The pathologist should be available for frozen section analysis. Incisions should be planned to permit complete excision of the biopsy tract if definitive wide resection is necessary. This generally involves making a longitudinal incision in line with either the foot or ankle (whichever the case may be). Careful study of imaging permits selection of the most direct path to the tumor while avoiding contamination of critical neurovascular structures. Development of skin and soft tissue flaps should be avoided, and meticulous hemostasis should be maintained. Frozen section analysis permits assessment of adequacy of the sample and an initial diagnostic impression. Morbid resection or amputation should not be performed based solely upon frozen section results. The surgeon should also discuss the possible need for fresh tissue (in addition to standard fixed tissue) with the pathologist. Fresh tissue is sometimes necessary for flow cytometry or cytogenetic analysis. Drain placement in line with the incision is used only if there is significant dead space or risk of hematoma. Surgical principles of incisional biopsy are summarized in Table 18-10.158 Table 18-10 Principles of Incisional Biopsy Tourniquet optional; elevate foot and do not use Esmarch tourniquet to exanguinate; if tourniquet is used, always deflate at conclusion to confirm hemostasis Longitudinal incision in line with foot or ankle; biopsy incision and tract must be completely excised if the lesion is malignant Do not create skin or soft tissue flaps; cut directly down to tumor and sample; do not spread and visualize Meticulous hemostasis is crucial; electrocautery; consider packing dead space with hemostatic material such as noncompressed Gelfoam If drain is to be used, place in line with incision so that drain tract can be easily excised with the biopsy incision Standard closure techniques and compressive dressing to prevent hematoma Bone sarcomas, specifically osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma, are chemotherapy responsive. They are generally treated with neoadjuvant (preoperative) chemotherapy before resection and then with additional adjuvant chemotherapy after resection. Chemotherapy is rarely used for the treatment of chondrosarcoma. Soft tissue sarcoma response to chemotherapy varies considerably with the specific pathology of the tumor. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is used for some high-grade soft tissue sarcomas, but most are treated with radiation and surgery. Isolated limb perfusion is a special technique of chemotherapy administration in which the circulation of a limb is isolated from the rest of the body (typically with temporary vascular bypass), and high doses of chemotherapy are administered to the isolated limb.49 This technique permits the use of chemotherapy agents and dosages that are too toxic for general systemic administration. This technique, although relatively uncommon in North America, has been frequently used in Europe and Asia with good results for the treatment of advanced soft tissue sarcomas and melanoma of the foot and ankle.49 Radiation therapy is part of the standard treatment for most high-grade soft tissue sarcomas. It has been shown to substantially decrease the risk of local recurrence in these tumors.161 Preoperative and postoperative radiation each have distinct advantages and disadvantages. Preoperative radiation generally requires a smaller total dose and smaller field of radiation. This may reduce the long-term morbidity associated with radiation treatment. Some have even suggested an improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy.155 Unfortunately, preoperative radiation may induce tissue fibrosis, making surgical resection more difficult. Preoperative radiation also has a higher wound complication and infection rate than postoperative radiation.135 Alternatively, postoperative radiation has a lower wound complication rate but may produce greater long-term radiation–induced morbidity. There are many advocates of both strategies. In adults, for soft tissue sarcomas about the foot and ankle, strategic radiotherapy may be advocated. In children with a defined soft tissue rhabdomyosarcoma, radiation may also be chosen to avoid a major amputation if major growth plates can be spared.96 Radiation plays a much smaller role in the treatment of bone sarcomas. Ewing sarcoma is radiosensitive, but definitive radiation is generally not advocated in the foot and ankle because definitive surgical resection is possible in this location. Furthermore, the effects of radiotherapy on the growing foot are quite devastating and compromise function compared with a below-knee amputation with a modern exoprosthesis. Radiation is also used for some benign but locally aggressive soft tissue tumors, particularly desmoid tumors. The most common method of radiation delivery to the foot ankle is external beam radiation. Brachytherapy is an alternative technique in which radiation catheters are surgically placed, and radioactive material then can be placed through them. It offers the potential advantage of administering higher local radiation doses to the tumor bed with less dosage to the adjacent healthy tissues.11 Foot and ankle tumor surgery differs from most trauma and reconstructive surgery of the foot and ankle because the prevention of tumor recurrence is often more important than restoration of function. This is certainly the case for malignant tumors and is also true of many benign but locally aggressive tumors. Risk of local recurrence is largely determined by two factors: the biology of the tumor and how the tumor is treated. In addition to his staging system, Dr. Enneking provided an intellectual framework for the different types of surgical resections (Table 18-11). He defined resections as intracapsular, marginal, wide, and radical (Fig. 18-1).58 These are roughly defined by how closely the surgical dissection plane comes to the tumor, with intracapsular resections cutting through tumor tissue and radical resection cutting far from the tumor. Within this framework, the surgeon plans the type of resection based upon the pathology of the tumor with wider resections performed for more aggressive lesions. It is very important to understand that the type of resection is not determined by the particular type of surgery (Fig. 18-2). For example, an amputation inadvertently performed through a tumor is an intralesional resection, whereas removal of a subcutaneous tumor with a cuff of normal surrounding fat is a wide resection. Although often useful as a surgical planning tool, the Enneking definitions have been largely replaced by the residual disease classification for reporting purposes in the literature (see Table 18-11).80a This system is defined by pathologic analysis of the specimen after resection as opposed to the preoperative plan. R0 is defined as no residual disease, R1 as microscopic residual disease, and R2 as gross residual disease. Use of these definitions for reporting ensures that investigators are defining surgical results by the same criteria. Table 18-11 Classification of Surgical Margins: Enneking and Residual Disease Classifications From Enneking WF: A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms, Clin Orthop Relat Res 204:9–24, 1986; Hermanek P, Wittekind C: Residual tumor (R) classification and prognosis, Semin Surg Oncol 10:12-20, 1994. Figure 18-1 Illustration of the different types of musculoskeletal tumor resections as described by Enneking. Benign soft tissue tumors and tumor-like conditions are the most common tumor of the foot and ankle. Incidence is difficult to define because many people with small benign tumors never seek treatment, and studies from specialized tumor centers invariably have referral bias because more complex cases are likely to be referred. A large, consecutive series (83 cases) of foot soft tissue tumors seen at the Hospital for Joint Diseases in New York found that 87% of the tumors were benign.93 Thirty-two percent of the benign tumors were ganglion cysts, and 21% were fibromas or fibromatosis. The ganglion cysts were primarily dorsal, and the fibromas were plantar. A series of 153 foot and ankle tumors at a tertiary orthopaedic oncology unit found 61% were benign, and the most common benign soft tissue diagnosis was pigmented villonodular synovitis and giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath.38 The discrepancy of these series likely results from referral bias because one study primarily collected cases from a foot and ankle service and the other from an orthopaedic oncology service. A wide array of pathologies accounted for the remaining diagnoses in both series. Table 18-12 lists the most common benign soft tissue tumors of the foot and ankle, their common locations, and their relative recurrence risk after excision. Plantar fibromas and fibromatosis are best characterized as a continuum of disease, ranging from small, isolated fibromas to extensive fibromatosis. Correspondingly, symptoms range from minimal to severe. The lesions occur most often along the medial border of the plantar fascia. The condition may present at any age, including children.63 Males are more frequently affected than females, and the whites of northern European ancestry are more commonly affected than other races. Many patients have a family history of palmar or plantar fibromatosis. Lesions are firm and fixed to the plantar fascia and produce discomfort on weight bearing because of the irregular contour of the plantar surface in the arch of the foot (Fig 18-3). Growth is generally slow and usually stops once the lesion reaches a size of approximately 2 cm. Older patients may have an associated Dupuytren contracture of the hands or Peyronie disease of the penis. Histologically, the lesions contain myofibroblasts similar to those seen in a Dupuytren contracture.48 The classic location of the lesion or lesions, especially in the setting of long-standing duration and personal or family history of the condition, facilitate clinical diagnosis without the need for advanced imaging or biopsy in many cases. Figure 18-3 Typical size and appearance of plantar fibromatosis along the medial border of the plantar fascia. Asymptomatic patients require no treatment. Symptomatic patients should be given a prolonged trial of nonsurgical therapy, including footwear modification and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Because the lesions extend into dermis and skin as well as the underlying fascia, it is difficult in many cases to obtain satisfactory surgical margins. Prior series have reported relatively high recurrence rates and significant surgical morbidity. Factors associated with recurrence have included bilateral disease, multiple nodules, and positive family history.4 Multiple different surgical techniques have been advocated, including marginal excision, subtotal fasciectomy,4 and wide excision followed by local soft tissue reconstruction.186 A 2000 study by Sammarco and Mangone154 reported a operative staging system with specific surgical recommendations after review of 21 surgically treated cases of fibromatosis. Multifocal disease, adherence to the skin, and deep extension to the flexor tendon sheath were the factors associated with increasing surgical difficulty. The authors advocated incisions placed in the non–weight-bearing portion of the plantar arch, routine use of loupe magnification, avoidance of full-thickness resection of plantar skin even in cases of dermal infiltration, and initial use of local wound care with avoidance of early skin grafting. The final point is analogous to the McKash open palm technique used by many hand surgeons in the treatment of severe Dupuytren disease. Delayed skin grafting was not associated with increased infection risk and avoided secondary procedures in many patients. Eighteen of 21 patients were satisfied with the procedure, and there were only two recurrences. Desmoid tumor is a benign but locally aggressive fibrous tumor that may occur anywhere in the body. It bears no clinical or histologic relation to plantar fibromatosis. Most extraabdominal desmoid tumors are sporadic, but some may be associated with the familial adenomatous coli (FAP) syndrome. FAP is characterized by diffuse development of colon polyps and predilection for early colon cancer.60 Young patients presenting with desmoids of the foot should be questioned about family history, and referral for genetic testing should be considered. A recent series from Massachusetts General Hospital identified the foot as the most common site of extraabdominal desmoids (45 of 234 cases).114 Historically, aggressive wide resection of desmoids, including those of the foot, has been advocated because of high recurrence rates.13 During the past decade, the understanding of this condition at many high-volume centers has shifted. Previously, desmoids were believed to have unrelenting continued local growth, but it has recently been demonstrated that many have long periods of stable size or even regression.65 This realization has led to a more conservative approach of initial observation at many centers. Surgical treatment has also become more conservative as microscopic positive margins have not been shown to adversely influence recurrence rates.78 Based upon these studies, acceptance of microscopically positive margins in order to preserve important neurovascular structures is appropriate in the treatment of this condition. This dermal-based lesion most commonly presents on the lower legs but can also be found on the feet. It is frequently painful or pruritic. Patients may relate a history of trauma or insect bite, but this association is not clearly defined in the literature. Physical examination reveals dimpling of the skin with lateral compression next to the lesion (Fitzpatrick sign).66 As the alternative name suggests, histologic analysis reveals a fibrohistiocytic proliferation; multiple subtypes have been characterized.201 Whether or not there is a continuum from benign dermatofibromas to dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is debated.84 Most patients are effectively treated with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition. Treatment with corticosteroid injection has been reported. Persistently symptomatic lesions can be resected with low recurrence rate.201 The subcutaneous form of granuloma annulare frequently presents as a superficial mass in the anterior distal leg or foot of children and adolescents.149 Although the more common dermal form presents with characteristic papules, the subcutaneous variety often lacks surface changes on visual inspection. MRI features have been described but are not specific for the condition.40 Histology reveals a granulomatous lesion with characteristic features best demonstrated with mucin staining. A series of 35 cases in children identified the scalp, anterior distal leg, and foot as the most common sites.118 The condition occurs more frequently in females than males. Although surgical biopsy is often required for diagnosis, resection is not recommended because the lesions usually resolve spontaneously. These are developmental anomalies of the vasculature rather than true clonal neoplasias. Hemangiomas typically arise in childhood and adolescence.153 When these tumors are superficial, a noticeable bluish discoloration is observed, associated with a soft, doughy mass (Fig. 18-4). More extensive lesions can have associated localized gigantism of adjacent bone and soft tissue. Proteus syndrome and Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome may both present with vascular malformation of the leg and foot with associated gigantism.81,171 Plain radiographs can show multiple small calcified phleboliths. MRI demonstrates a characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance and can better define the anatomic extent of larger lesions.137 Lymphangiomas share similar presentation and histology with hemangiomas, with the exception that the vascular channels are lymphatics rather than capillaries.194 Hemangiomas are consequently more vascular at surgical resections. Structurally, these tumors can be of the cavernous, capillary, or mixed type; the port-wine capillary hemangiomas are most common in the foot. Treatment is initially conservative, with observation of asymptomatic lesions and compression stockings and analgesics for symptomatic lesions. A recent randomized controlled trial of oral propranolol for infantile hemangiomas showed efficacy for children up to 5 years of age.82 Nonsurgical procedures, specifically sclerotherapy191 and embolization,12 have been used with encouraging results. Symptomatic lesions in which conservative measures have failed require surgical resection. Marginal or even intralesional excision is advocated for these benign lesions. Recurrence rates reported in the literature vary widely, with discrepancies likely resulting from differences of both the tumors and techniques. A 1993 study reported a 48% recurrence rate, but many of these patients had extensive lesions.155 A series of 89 surgically treated hemangioma patients from Harvard found an overall 19% recurrence rate and 13% rate of revision surgery for recurrence. All patients in the series were treated with marginal or intralesional resections. The role of margins in recurrence was analyzed in a 2007 study from the University of Minnesota. Recurrence rate was 7% with wide or marginal resection, 35% with intralesional resection without gross tumor remaining, and 67% with gross residual tumor.14 Based upon these data, removal of all gross tumor at a minimum, and preferably marginal resection, is advocated when surgery is indicated. Preoperative embolization may facilitate a better resection margin in cases of large hemangiomas. Glomus tumors, also called glomangiomas, are benign vascular tumors that have their peak incidence in the 20- to 40-year-old age range. They arise from the glomus body tissue of the dermal layer of the skin. This tissue contains an arteriovenous shunt with sympathetic innervations.108 It is thought to shunt blood flow away from the skin in response to cold temperatures. Glomus bodies are most numerous in the tips of the fingers and toes. There are rare case reports of glomus tumors in the hindfoot,120,144 but most occur under the nail bed. Subungual glomus tumors are associated with a female predominance of 3 : 1.170 These tumors typically manifest with a bright red to bluish discoloration beneath the nail bed and are associated with lancinating pain that worsens with cold exposure or direct pressure. They are usually less than 1 cm in diameter. Radiographs may show well-marginated bony erosion over the dorsal surface of the distal phalanx. Treatment consists of surgical resection of symptomatic lesions. A 2003 case series reported excellent results with subperiosteal elevation of skin, nail, and nail matrix as a single flap, followed by excision of the tumor from within the flap.85 The authors reported complete resolution of symptoms and no recurrences in their series of seven cases. Pain relief is usually prompt, and recurrence is unusual. In any lesion found under the nail, the possibility of malignant melanoma should always be considered in the preoperative differential diagnosis. Schwannoma (neurilemoma, neurilemmoma, neurolemmoma) is a benign tumor of nerve sheath (Schwann cell) origin with a peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades of life. Males were more commonly affected than females in a review of 104 cases from Scotland.90 The tumor is usually solitary, well encapsulated, and on the surface of a peripheral nerve. Solitary Schwannomas of the foot are quite rare, with only case reports noted in the literature.202 Schwannomas can continue growing to a very large size even in the foot.111 Patients present with a painful nodule often associated with a positive Tinel sign in the distribution of the affected nerve. Schwannomatosis (previously called neurofibromatosis type 3) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by diffuse development of schwanomas.109 Unlike neurofibromas, schwannomas usually have a discrete plain between the tumor and the nerve fascicles. The tumor can usually be shelled out of the nerve sheath without damage to the nerve fibers themselves (Fig. 18-5). Use of loupe magnification and microsurgical instruments may be beneficial when critical nerves are involved. Recurrence is rare, and these tumors have little malignant potential.

Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors

Clinical Evaluation

History

Symptom or Complaint

Significance

Long duration with stable size

Likely benign

Waxing and waning size

Consider ganglion cyst

Burning pain or numbness

Nerve sheath tumor

Night pain

Tumor or infection

Marked relief with NSAIDs

Osteoid osteoma

History of blunt trauma

Hematoma or heterotopic ossification

History of penetrating trauma

Infection or foreign body

Personal history of malignancy

Metastatic disease

Physical Examination

Examination Finding

Significance

Fixed to bone

Osteochondroma, osteophyte, tumor arising from bone

Transillumination

Fluid-filled cyst

Bruit on auscultation

Vascular tumor

Tinel positive

Neural tumor

Fatty consistency

Lipoma

Imaging Studies

Radiographs

Radiographic Finding

Description

Significance

Site within bone

Epiphyseal, metaphyseal, diaphyseal

Predilection of particular tumors for specific sites; example: chondroblastoma-epiphysis

Site within bone

Central, eccentric, periosteal

Predilection of particular tumors for specific sites; example: osteoid osteoma-periosteal

Zone of transition (border)

Sclerotic, well defined, poorly defined

Sclerotic usually slow growing; poorly defined often faster growing

Bone loss

Geographic, moth eaten, permeative

Geographic usually less aggressive; moth eaten and permeative usually more aggressive

Periosteal reaction

Present, absent

Presence suggests more aggressive lesion

Matrix

Absent, chondroid, osteoid

Suggests specific pathology

Soft tissue mass

Present, absent

Soft tissue mass associated with bone lesion typically suggests a more aggressive lesion

Modality

Finding

Pathology

Radiograph

Phleboliths

Hemangioma

Radiograph

Fallen leaf sign

Simple bone cyst

Radiograph

Sunburst periosteal reaction

Osteosarcoma

Radiograph

Onionskin periosteal reaction

Ewing sarcoma

CT or radiograph

Cortical ridus

Osteoid osteoma or Brodie abscess

MRI

“Cluster of grapes”

Hemangioma

Computed Tomography

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Nuclear Imaging

Staging

Study

Purpose

Radiographs of involved area

Diagnosis and local assessment

MRI with IV contrast of involved area

Define local extent and plan surgery

CT of involved area

Occasionally used to better define local anatomy

CT chest

Identify pulmonary metastasis

Whole body bone scan

Identify skeletal metastasis

Biopsy

Technique

Advantage

Disadvantage

Needle (general)

Less trauma than open

Less tissue than open

Core needle

Can show tissue architecture in addition to cytology

More traumatic than fine needle aspiration

Fine needle

Less traumatic than core

Only provides cells; no tissue architecture can be analyzed

Open (general)

More tissue than needle

More traumatic than needle

Incisional

Less extensive than excisional biopsy

Requires second operation for definitive resection

Excisional

No further surgery required if done appropriately

More traumatic; second operation is more complicated if any margins are positive

Radiation and Chemotherapy for Foot and Ankle Tumors

General Principles of Surgical Treatment for Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors

Benign Soft Tissue Tumors

Fibrous Tumors

Fibroma and Fibromatosis

Desmoid Tumors (Aggressive Fibromatosis)

Dermal Tumors

Dermatofibroma (Benign Fibrous Histiocytoma)

Granuloma Annulare

Vascular Tumors

Hemangioma and Lymphangioma

Glomus Tumor

Neural Tumors

Schwannoma (Neurilemoma)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree