Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Daniel J. Sucato

Key Points

Introduction

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is a primarily posterior migration of the epiphysis on the metaphysis in the skeletally immature patient. The clinical presentation of these patients is somewhat challenging because they often have painful symptoms in the thigh and knee region, which makes the diagnosis difficult and often delayed. Chronic or stable SCFE presents with discomfort and can lead to the more serious acute or unstable SCFE, which presents as a hip fracture with acute pain and an inability to bear weight and carries a high risk for developing avascular necrosis. The cause of SCFE is unknown; however, relative weakening of the physis compared with the size and activity of these patients is often a contributing factor. Treatment, especially for unstable SCFE, continues to evolve fairly rapidly with more aggressive surgical treatment to limit the incidence of avascular necrosis (AVN) and residual deformity, which can lead to femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

This chapter describes the current perspective on slipped capital femoral epiphysis with traditional information on the incidence, origin, and classification. An up-to-date review of current surgical management and thinking behind these treatments will be discussed.

Incidence and Epidemiology

SCFE is estimated to occur in approximately 2 per 100,000 population and is somewhat dependent on race and geographic region. African Americans living in the Eastern United States are more prone to SCFE.1 Males have a greater predisposition to developing SCFE than females, with some studies suggesting that it is up to five times more likely to occur in the male population. More current studies demonstrate a 2 : 1 or 3 : 2 ratio of males to females, suggesting a decrease in male prevalence over time.2,3

SCFE is more commonly seen in the summer months; June is a common month for this condition in North America,4 and July is more common in Europe.5 This is geographically determined because time-related incidence has not been seen in the Southern hemisphere.

Race is a characteristic feature of slipped capital femoral epiphysis; African Americans and Hispanics more commonly develop SCFE than Caucasians.6 Increased prevalence of bilateral SCFE did not occur more commonly in black children.6 Loder further analyzed Polynesian children, who demonstrated the highest prevalence of slipped capital femoral epiphysis.3 The left hip is more commonly affected than the right side.

The cause of SCFE is unknown, although some have suggested that because children are more commonly right-handed, the sitting posture during school time predisposes the left hip to SCFE.7 The most common age for the occurrence of SCFE is the adolescent period, which is generally considered the time of maximal skeletal growth. Boys are most commonly affected during the ages of 13 to 15 years; girls in the 11 to 13 year age group are more commonly affected.2–6 SCFE can be seen in the younger patient (<10 years of age), and in this setting, a careful endocrinopathy workup, including thyroid function assessment, should be performed.8 Bilateral involvement of slipped capital femoral epiphysis is generally regarded to be approximately 25%; this is important to realize when evaluating a patient who presents with a SCFE. It is mandatory that anteroposterior (AP) and frog-leg pelvis radiographs are performed to visualize both hips to ensure that bilateral SCFEs are not present.2,9

Classification

The most common classification utilized to date is the one described by Loder and coworkers in defining a stable versus an unstable slip (Fig. 42-1). This is an important classification because it predicts the incidence of avascular necrosis (AVN) in the setting of in situ pin fixation treatment. Loder and associates described 55 patients who presented with an acute SCFE and based their classification on the ability to bear weight. For those hip patients who could bear weight even with crutches, this was defined as a stable slip, and the incidence of AVN in their series was 0% (0 of 25 SCFEs). In stark contrast, patients who were unable to ambulate or get up with crutches were defined as having an unstable SCFE, and their incidence of AVN was 47% (14 of 30 patients).10 This classification system has been adopted and is the most common classification utilized today because it does prognosticate the incidence of AVN and has been studied and confirmed by others.11–14

Figure 42-1 Stable and unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). A, Stable: a mild slip with no loss of continuity between the epiphysis and the metaphysis. B, Unstable: note the significant displacement of the epiphysis with the appearance of an acute event.

Older classifications include the one based on the chronicity of the SCFE. The acute SCFE is one in which symptoms have occurred for 3 weeks or less. This typically coincides with having an unstable SCFE in that the patient has an acute event leading to severe symptoms and usually the inability to ambulate. Acute SCFE is often difficult to distinguish from the Salter-Harris type 1 fracture, which also occurs through the physis; however, it is generally agreed that the type 1 epiphyseal fracture occurs secondary to significant trauma in an otherwise normal patient without prodromal symptoms. This distinction is important because the Salter-Harris type 1 fracture often carries an incidence of AVN of nearly 100%.

Chronic SCFE is characterized by symptoms for longer than 3 weeks and is, by far, the more common slip, seen in up to 85% of cases of SCFE.3 Traditionally, chronic SCFEs have been described with radiographic findings of proximal femoral neck morphologic changes with bending of the femoral neck and lipping inferiorly and posteriorly, suggesting chronicity.15 Acute-on-chronic SCFE is a traditional classification in which prodromal symptoms have been present for longer than 3 weeks, and a sudden event led to the acute unstable situation. More recently, it has been thought that in all cases, SCFE is an acute event on chronic symptoms that has been confirmed by the recently advocated approach of open reduction of the unstable SCFE in which posterior and medial callus is seen.16

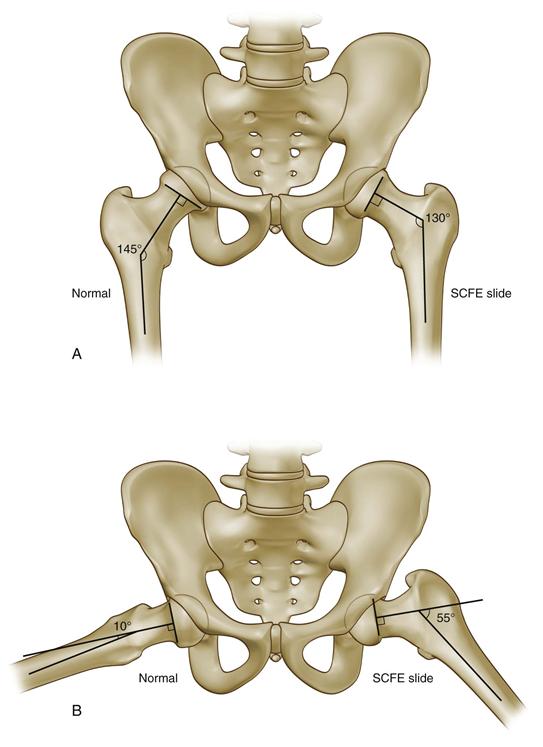

The most commonly used radiographic classification was reported by Southwick and describes the femoral head–to–femoral shaft angle on AP and frog-leg radiographs (Fig. 42-2).17 Mild slips are ones in which the head-shaft angle is 30 degrees or less, moderate slips between 30 and 60 degrees, and severe slips greater than 60 degrees. These are all comparisons with the contralateral hip when it is normal. Certainly, challenges arise with this classification secondary to bilaterality in that no comparison can be made with adequate radiographs, difficulty is associated with positioning a painful hip, and a complex three-dimensional deformity is present in this condition.18

Figure 42-2 Southwick radiographic classification. This measures the angle between the axis of the femoral shaft and the axis of the epiphysis. A, On anteroposterior (AP) radiograph, the angle subtended by the anatomic axis of the femur and perpendicular to the base of the epiphysis is the slip angle. In this example, the slip angle is 145 − 130 degrees = 15 degrees. B, On the frog-leg pelvic radiograph, the same lines are drawn. In this example, the slip angle is 55 − 10 = 45 degrees. Mild is less than 30 degrees, moderate 30 to 60 degrees, and severe greater than 60 degrees.

Causes

Causes of SCFE are essentially unknown at this point; however, several features of SCFE provide some insight as to possible etiologic factors. Many of these patients have a high body mass index (BMI) along with clinical evidence of endocrinopathies. Mechanical factors that may play a role in this condition include the larger size of the patient relative to skeletal maturity. Some have proposed that the perichondrial ring, which encircles the physis at the cartilage-bone interface, is thin, and its resistance to shear forces is diminished.19,20 Considerable study of version of both the proximal femur and the acetabulum has been performed using computed tomography (CT) imaging. Retroversion of the proximal femur has been reported as a more common finding in SCFE,21 and acetabular version has been reported to be normal.22 Other anatomic changes include an anecdotal observation by the author’s group that protrusio is more commonly seen in these patients. Finally, the slope of the proximal femur has been reported to be greater than that of the unaffected side (11 degrees vs. 5 degrees), and this may contribute to the occurrence of SCFE.23,24 All of these factors, together with increased size of these patients, may play a mechanical role in the development of SCFE.

Endocrine factors have been studied extensively because many patients present with large size and hypogonadal features. In addition, endocrine abnormalities such as hypothyroidism,25–27 growth hormone administration,28–31 renal failure32,33 and panhypopituitarism with intracranial tumors,8 and hyperparathyroidism34 have been reported to be risk factors for SCFE. These patients typically present at 10 years of age or younger.8 Many patients who present with SCFE at a young age are evaluated for the first time for endocrinopathies, and the diagnosis of hypothyroidism is the result. Patients younger than 10 or older than 16 years of age are four times more likely to have an atypical SCFE and endocrine workup, especially thyroid, and growth hormone deficiency is important.35

Clinical Presentation

Patients with SCFE typically present in two main ways. In the first, more common presentation, the patient reports thigh, knee, or, less commonly, hip pain, which is insidious in onset and is often sporadic. Symptoms are worse with activity and better with rest, with the character of the pain typically described as aching-type symptoms, rather than sharp pain. Thigh and knee pain often contributes to the delay in diagnosis because this distracts the physician away from the hip, and the stable slip may become an unstable situation.36,37 The presentation of any adolescent with thigh or knee pain, especially in the face of an external foot progression angle in an overweight individual, should alert the physician to this diagnosis (Fig. 42-3). This is the presentation of the patient with stable SCFE; making the diagnosis is critical because outcomes of in situ pinning for stable slips are significantly better than for the same treatment for unstable SCFE.

Figure 42-3 The typical patient presentation for a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). Obligate external rotation is seen with hip flexion.

The physical examination of the patient with chronic SCFE is characteristic and reveals an external foot progression angle and often a Trendelenburg lurch secondary to relative abductor weakness from decreased abductor muscle length secondary to the posterior slip of the epiphysis. Examination of the hip while the patient is in the supine position reveals the classic finding of “obligate external rotation” during attempted flexion of the hip (see Fig. 42-3), that is, patients are unable to bring the hip to a neutral position, and instead can have marked external rotation of the hip during flexion. In the severe Southwick angle SCFE, the patient may be unable to flex the hip to 90 degrees and often are able to flex to only 60 degrees, which is associated with anterior groin pain.

Unstable or acute and chronic SCFE presents very similarly to a hip fracture, with the patient in acute distress and having significant hip symptoms. Any attempted movement of the affected lower extremity will cause significant apprehension by the patient and significant pain. Patients are unable to get up and can be transported only via stretcher and ambulance.

Radiographic Findings

Patients presenting with a chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis will have several key features seen on an AP radiograph. AP and frog-leg pelvis radiographs are mandatory to identify and confirm the diagnosis; they also allow one to fully visualize the contralateral hip to ensure that the SCFE is not occurring on that side.

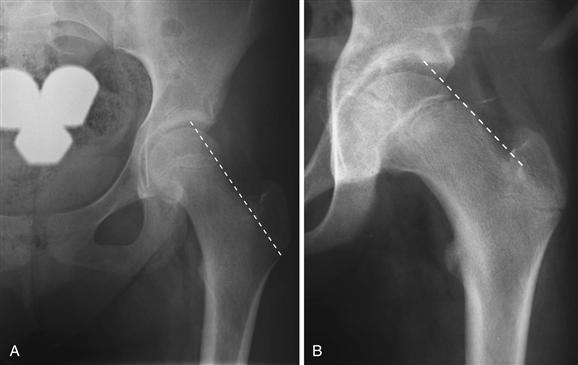

On the AP radiograph, findings may be subtle. Klein’s line should be utilized to assist in diagnosis.38 This line is drawn as a tangent along the lateral aspect of the femoral neck and should intersect the lateral aspect of the epiphysis in the normal situation. When it does not intersect, this confirms the SCFE (Fig. 42-4). Other findings include a slightly widened physis with some irregularity.39,40 The metaphyseal blanch sign as described by Steel is due to femoral neck and posteriorly displaced capital epiphysis overlap.41 The frog-leg lateral radiograph is confirmatory for SCFE and demonstrates posterior migration of the epiphysis on the metaphysis; it is the best radiograph to identify this condition (Fig. 42-5). In a chronic situation, appositional bone is identified. Although other radiographs have been described, including the true lateral radiograph, these are not typically utilized and can often be difficult to obtain, especially when the patient is overweight.

Figure 42-4 Klein’s line: On the anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiograph, a line tangential to the lateral aspect of the femoral neck is drawn. A, Intersection of the epiphysis by Klein’s line is normal. B, When Klein’s line does not intersect the epiphysis, a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is noted.

Figure 42-5 The utility of the frog-leg pelvic radiograph in identifying a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is noted. The anteroposterior (AP) radiograph suggests an SCFE; however, the posterior slip of the epiphysis seen on the frog-leg pelvic radiograph confirms the SCFE. Note that the posterior remodeled bone seen on this radiograph is due to the chronic nature of the SCFE.

Computed tomography is not typically utilized in the diagnosis of SCFE. However, it has great utility following treatment in several situations, including determining whether the physis has healed or whether there has been penetration of an implant following surgery, and in the setting of avascular necrosis.

Technetium bone scan is occasionally useful in the setting of delayed presentation of an unstable SCFE, to determine whether perfusion to the epiphysis is present. Ultrasonography has a limited role in North America; however, it has been utilized in Europe to help define instability of the epiphysis, defined by a joint effusion.42 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a limited role in the diagnostic workup for SCFE; however, it can be utilized in the situation where perfusion to the epiphysis is being evaluated, most commonly, in the author’s practice, when there has been a delay in presentation of an unstable SCFE.

Treatment

The traditional treatment for stable slipped capital femoral epiphysis is in situ pinning. This method has withstood the test of time and requires little surgical time; it generally yields overall good results with respect to the physis closing, and it maintains the position of the epiphysis relative to the metaphysis. Other methods include bone peg epiphysiodesis, casting, and open reduction. However, by far the most common treatment is in situ pinning.

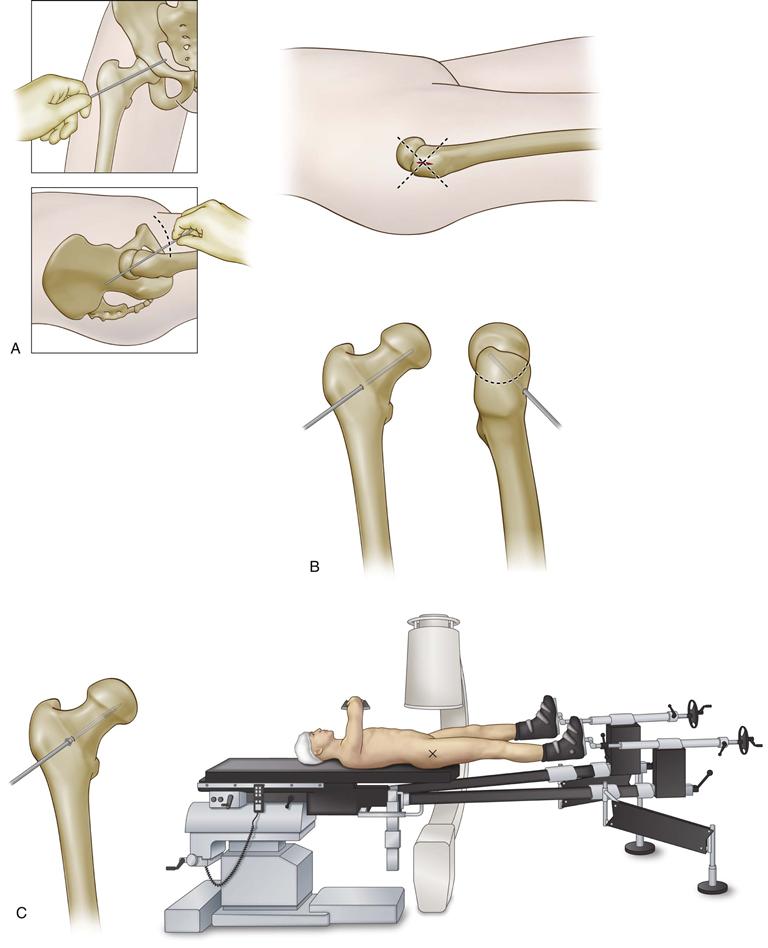

For in situ pinning, the patient may lie on a flat-top radiolucent table or on a fracture table (author’s preferred method). Imaging of the hip is then performed to identify the starting incision. If a fracture table is used, the patient is placed in the supine position, and the contralateral hip is fully abducted to allow access to the fluoroscopy unit (Fig. 42-6). An AP projection of the hip is used to draw a line on the skin in-line with the axis of the neck, with its trajectory in the center of the epiphysis.43 A lateral radiograph is then performed and a guide wire is placed onto the skin in-line with a projected screw trajectory into the center of the femoral head. This usually begins in the anterior aspect of the femoral neck, especially when there is significant deformity. The intersection of these two lines on the skin is the point for the skin incision; a small skin incision measuring a centimeter in length is then made. A large hemostat can be placed through the soft tissues and onto the anterior femoral neck at the starting point and is visualized under fluoroscopy. The author usually utilizes the lateral radiograph to first identify this starting point, along with a guide wire from the 6.5 mm or 7.3 mm cannulated system placed in the center of the femoral neck relative to the superior and inferior femoral necks. The guide wire is advanced in-line with the skin line, which had been placed during the AP fluoroscopy image. The lateral radiograph is utilized to advance the guide wire into the center of the femoral head of the subchondral bone.

Figure 42-6 Technique for percutaneous pinning of a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) on the fracture table. A, Skin markings are made on anteroposterior (AP) and lateral fluoroscopy images, and the intersection of the two lines marks the skin incision. B, The guide wire is placed onto the anterior femoral neck and is imaged on the lateral fluoroscopy image. The guide wire then is partially advanced using the lateral fluoroscopy image and following the anterior skin marking. The guide pin is advanced across the physis into the subchondral bone. C, After the appropriate length is measured, a fully threaded screw is placed across the physis into the epiphysis, with at least four threads crossing the physis.

Next, the guide wire is confirmed to be in good placement in both AP and lateral projections. A measuring stick is used to determine the length of the screw. The anterior cortex can then be tapped. Next, a fully threaded, stainless steel 6.5 mm or 7.3 mm screw is advanced over the guide wire to the level of the subchondral bone. It should be placed in the center of the femoral head so that maximum purchase of the screw is attained; this allows one to place the screw in a safe manner. Four screw threads crossing the physis into the epiphysis should be the goal. After placement, the guide wire can be pulled back a bit to allow the tip of the screw to be visualized under fluoroscopy. Next, the hip is put through a range of motion to allow for the near-far-near technique, so that the screw is placed deep into the epiphysis without penetrating into the hip joint.44

A stable SCFE usually requires single screw fixation because the epiphysis has moved slowly over time and should be relatively stable. If a secondary screw is utilized, the initial screw should be placed in the central epiphysis; the second screw could then be placed more peripherally and preferably in the inferior aspect of the epiphysis to maintain blood flow to the epiphysis. If the bony anatomy is somewhat small, then a smaller-diameter screw (5.5 mm or 4.5 mm) can be utilized for the second screw.

Postoperative management of the patient varies across centers but usually includes a short time of using crutches while fully weight bearing, usually for 6 weeks. This is somewhat arbitrary, and the crutches most likely are not necessary; however, it does slow the child down, and healing occurs during this time. The length of time needed for the physis to heal is dependent on many factors, including the age of the patient and the slip angle with younger patients with more severe deformity that takes longer to heal. It is important that patients have significant improvement in their pain following in situ pinning because a properly secured epiphysis will become asymptomatic. If this does not occur postoperatively, one must be suspicious that there is not enough stability, or that loosening has occurred over time.

Stainless steel screws are preferred by the author because titanium screw heads can strip if they require removal. In situ pinning using cannulated screws demonstrates optimal results with screws in the center of the epiphysis45 or again in the inferior-posterior position.46 The number of pins is generally one, and several studies have demonstrated excellent results. In a review of 114 hips in which treatment with one, two, or three screws or pins was provided, the incidence of pin-related complications was directly related to the number of pins. Investigators suggest single pin fixation in the stable fracture.47 A similar study demonstrated overall 91% good results with single screw fixation compared with 74% with multiple pins48; others have demonstrated similar results using single screws.49–51

Pin screw location has been studied in relation to subsequent further slip, and the central screw position is most ideal.46 The eccentrically placed screw has been directly related to further slip progression.45,49 Placement of screws can be associated with complications such as pin joint penetration, which can lead to chondrolysis as first described by Walters and Simon.44 It is important to put the hip through a range of motion following screw placement to ensure that it is subchondral. Other methods used to ensure safe screw placement include injecting dye through the cannulated screw to see whether dye enters the joint indicating joint penetration52 and endoscopic inspection of the drill hole.53 Screws should not be placed distal to the lesser trochanter because this leads to a greater likelihood of femoral neck fracture, specifically subtrochanteric fracture,49,54-56 which may lead to significant malunion or nonunion, as well as avascular necrosis. When the screw is placed too far proximally in the anterior position, screw impingement may occur,57 so care should be taken to start the screw as distal as possible, especially when there is significant deformity, because the starting position requires it to be placed anteriorly on the femoral neck.

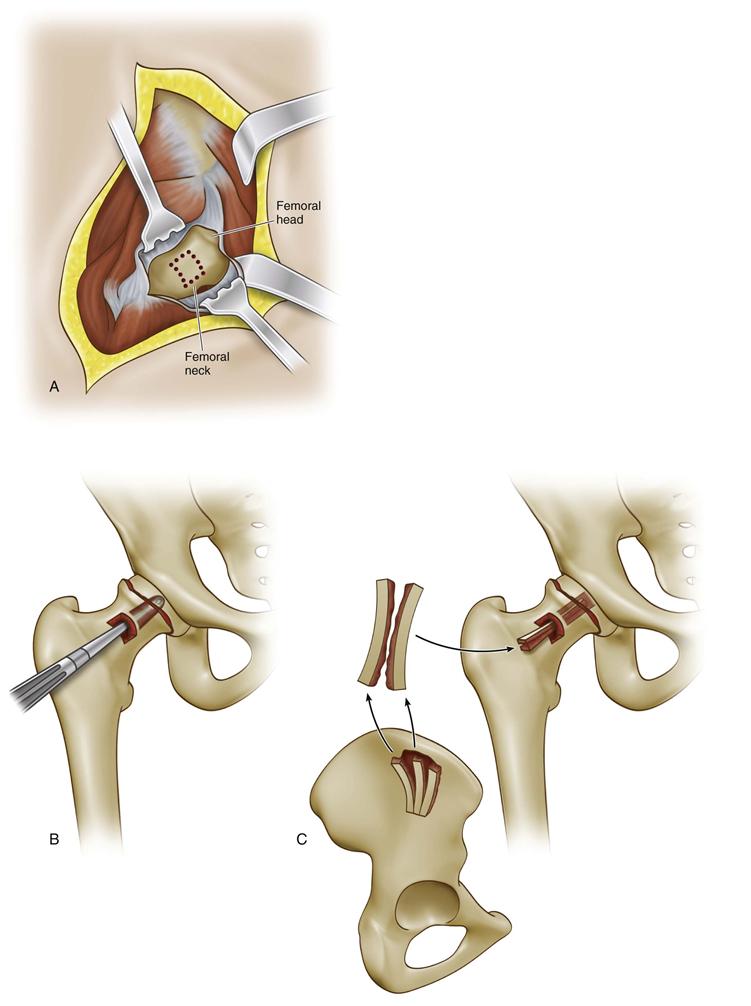

Other operative techniques for stable slips include bone peg epiphysiodesis, in which a portion of the residual physis is removed by drilling and curettage, and a peg of autologous bone graft from the iliac crest is placed across the physis to achieve fusion or healing (Fig. 42-7). This technique can be supplemented with screws and can be utilized in both the stable and the unstable situation. This technique has been described by many authors, including Heyman and Herndon.58 Indications for this are somewhat limited but may include the patient with delayed union who has severe deformity in an attempt to get fusion across the physis. Generally, it is not utilized as a routine procedure for the typical stable SCFE.

Figure 42-7 Bone peg epiphysiodesis. A, An anterior or anterolateral approach to the femoral neck is performed, a small capsulotomy is made, and a small cortical window is placed on the anterior neck. B, A larger cannulated drill is used to remove the central physis and create a tunnel for the bone graft. C, Tricortical autologous iliac crest bone graft is taken and is used to cross the physis into the femoral epiphysis. The anterior cortical window can then be replaced, and the joint capsule is closed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree