Shoulder/Humerus: Surgical Treatment for Metastatic Bone Disease

Kristy L. Weber

The previous chapters have focused on the resection of primary bone tumors and reconstruction of the defect or on the issues related to complex revision surgery about the shoulder and humerus. This section is focused on the treatment of patients with metastatic bone disease (MBD) of the humerus, which is the second most common long bone where this occurs. The goals of surgical treatment in patients with MBD are to (a) provide pain relief and (b) restore function. The surgical treatment is palliative rather than curative, and every effort should be made to provide the most durable reconstruction possible so that the terminally ill patient does not have failure of the reconstruction. It should be assumed that the reconstruction will be load-bearing, as pathologic fractures may not heal even with radiation. The surgical concepts often vary from those employed for patients with traumatic humerus fractures. Patients with MBD are at risk for disease progression and resultant continued bone loss, thus necessitating a different approach to surgical fixation.

INDICATIONS

Patient Requirements

Has a destructive lesion in the humerus with an actual or impending fracture

Able to tolerate surgery and anesthesia given comorbidities

Anticipated life span that will make risk/benefit profile worthwhile

Prophylactic Fixation

High risk of fracture (osteolytic lesion, cortical destruction, histology not responsive to radiation/chemotherapy)

If patient requires stable upper extremity for weight bearing (i.e., requires crutches or walker due to lower extremity disease) or for bed-to-chair transfers

Fixation of Pathologic Fracture

Fracture has low chance of healing

Patient in substantial pain uncontrolled by medication or radiation

Internal fixation (intramedullary nail) requires unaffected bone at proximal and distal ends of implant to allow durable fixation

Resection of Proximal or Distal Humerus

No substantial bone remaining in which to anchor internal fixation

High likelihood of failure of internal fixation

Solitary metastasis (controversial)

SPECIFIC ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS/INDICATIONS

Anatomic Considerations for Fixation/Reconstruction—Proximal Humerus

Resection and reconstruction with megaprosthesis—when there is not adequate bone for stable fixation with an intramedullary nail

Locked intramedullary nail extending throughout humerus—if there is adequate proximal and distal bone for fixation

Anatomic Considerations for Fixation/Reconstruction—Humeral Diaphysis

Locked intramedullary nail extending through the humerus is the most commonly used procedure.

Intercalary spacer when increased, local control is warranted despite the risk of resection—used with extensive diaphyseal bone loss but intact proximal and distal segments

Anatomic Considerations for Fixation/Reconstruction—Distal Humerus

Crossed flexible nails inserted from humeral condyles ± methylmethacrylate supplementation—when entire humerus requires some intramedullary support

Dual plate fixation ± methylmethacrylate supplementation—when a stable construct is required and there are no additional proximal lesions

Resection and reconstruction with segmental elbow replacement—when there is not adequate bone for distal internal fixation.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Patient with limited life span (anticipated length of life does not justify the risks of surgical procedure)

Small metastatic lesions that have not fractured (especially those that are radiosensitive)

Minimally displaced fracture that can be easily managed in a sling or clamshell brace (i.e., multiple myeloma often heals with appropriate systemic therapy)

Extensive comorbidities (pulmonary metastasis) prevent safe general or regional anesthesia

Nonsurgical options for treatment include functional bracing, external beam radiation, bisphosphonates, and radiofrequency ablation.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Patients with a destructive humeral lesion over the age of 40 years are most likely to have metastatic disease, which is the subject of this chapter. It is important, however, that the workup confirms this diagnosis as primary bone sarcomas occur in the humerus and would be treated quite differently in anticipation of a possible cure (1).

History

Pain—severity, anatomic location, timing (rest, activity-related, night), radiation of pain, medication requirements, interventions that relieve pain (ice, heat, NSAIDS, sling), duration (days, weeks, months),

and progression (improving, worsening). Pain from a malignancy is often persistent, progressive, and present at rest/night.

Neurologic symptoms—paresthesias, numbness in the extremity

Constitutional symptoms—fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss, fevers, chills

Symptoms related to common cancers that metastasize to bone—shortness of breath/dyspnea/pleuritic pain/hemoptysis (lung), hematuria/flank pain (kidney), breast mass/pain (breast), urinary frequency/pain (prostate), heat/cold intolerance (thyroid), and change in bowel habits/bleeding (colorectal)

Recent history related to arm—trauma to arm, appearance of lumps/masses, and new/changed skin lesions

Personal medical/social/family history—history of cancer (even if remote), prior radiation/chemotherapy, dates of most recent tests (mammogram, colonoscopy, prostate examination, pap smear), smoking history, exposure to chemicals (asbestos), and family history of cancers (breast, colon, etc.)

Physical Examination

Evaluate for soft tissue masses, tenderness, swelling, decreased range of motion, and neurovascular compromise of arm/shoulder/elbow

Evaluate for regional lymphadenopathy

Complete blood count

Anemia—advanced metastatic disease, multiple myeloma

Leukocytosis—leukemia

ESR-erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein (elevated with advanced cancer or infection)

Chemistry panel

Hypercalcemia—advanced metastatic disease

Abnormal calcium/phosphorus—metabolic bone disease (osteomalacia, hyperparathyroidism, rickets)

Elevated alkaline phosphatase—Paget disease

Urinalysis

Microscopic hematuria—renal cell carcinoma

Protein electrophoresis/Immunofixation

Serum/urine studies abnormal in multiple myeloma

Cancer markers

Tests for specific anatomic locations of primary disease (thyroid function tests, prostate specific antigen, CA-125, carcinoembryonic antigen)

Imaging

Plain radiographs

Obtain in two planes

Image entire humerus to include shoulder/elbow

Lytic (lung, kidney, thyroid, colorectal, myeloma, lymphoma) versus mixed (breast) versus blastic (prostate) lesions

Assess cortical involvement and size of lesion

Assess quality of uninvolved bone

Three-dimensional imaging of the metastatic lesion is not usually necessary

Computed tomography (CT)

Useful for staging disease (chest/abdomen/pelvic CT)

Can assess cortical integrity better than plain radiographs (but usually not necessary)

Magnetic resonance imaging

Not usually necessary in the humerus for metastatic disease

Technetium bone scan

Useful for staging studies to assess additional sites of bone metastasis

False-negative results in multiple myeloma

Biopsy

If the surgeon is not 100% confident that the humeral lesion is a metastasis, a biopsy (needle or open) should be performed

If the patient has known cancer and metastasis to multiple sites including bones, then no biopsy is necessary and treatment can proceed

Management of Comorbidities

Patients with metastatic disease often have multiple comorbidities due to the cancer or their age including hypercalcemia, impending fractures, cervical spine metastasis with potential instability, primary or metastatic lung cancer, and medical problems (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease).

Consult with anesthesiology, internal medicine, oncology, and/or cardiology services as needed preoperatively

If there are known spine metastasis or neck pain, cervical spine imaging is suggested before intubation

Obtain appropriate preoperative laboratory studies, and type and screen/cross for intraoperative blood products

Embolization

Consider preoperative embolization for patients with hypervascular metastasis (renal cell carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, multiple myeloma) if a tourniquet cannot be used. This can be done the day prior to the procedure or the morning of the procedure for optimal results (2).

As contrast dye is used for the embolization procedure, check for Basal urea and nitrogen/creatinine and discuss with the interventional radiologist if the results are abnormal. This is especially important for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma as they frequently have only one functioning kidney.

Equipment Needs

Intraoperative fluoroscopy (if internal fixation is planned)

Intramedullary nail versus proximal humeral megaprosthesis versus intercalary spacer versus intramedullary flexible nails versus segmental distal humeral/elbow replacement versus plates/screws

Methylmethacrylate

Postoperative sling/immobilizer

Considerations in the Operating Room

Position and draping

For proximal humeral prosthetic reconstruction or antegrade intramedullary nail placement, consider a beach chair position with the patient’s head padded and secured

For distal humeral reconstruction or retrograde flexible crossed nails, consider a lateral position on a beanbag

The patient should be prepped and draped with the entire arm free up to the neck. The patient should be positioned with the arm slightly off the table and secured if fluoroscopy is to be used.

Preoperative antibiotics should be given as per routine

Urinary catheter—depending on the length of the planned procedure, expected blood loss, and comorbidities

TECHNIQUE

Proximal Humerus

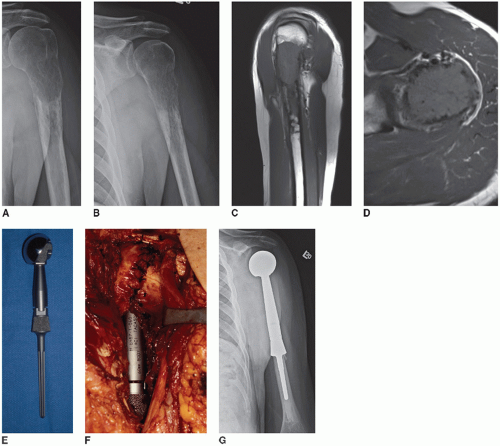

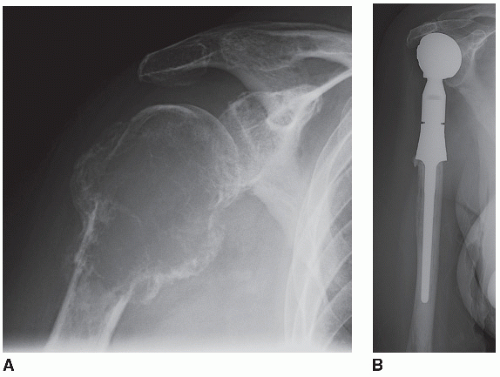

1. Proximal humeral resection/reconstruction with megaprosthesis (Figs. 33.1 and 33.2)

An anterior approach to the shoulder and humerus is used. Landmarks (coracoid process, acromion, clavicle) should be outlined prior to the incision. The incision is lateral to the true deltopectoral interval as it extends proximally to the superior aspect of the shoulder midway between the coracoid and the lateral aspect of the acromion process. Distally follow the lateral aspect of the biceps as far as necessary toward the elbow, depending on the length of planned humeral resection. The fact that the resection is being performed for metastatic disease means that a wide margin is usually not necessary (radiation is added postoperatively if an intralesional resection is performed). Often the surgeon will want to preserve tissue to improve function, which may lead to positive margins. If a truly wide resection is performed, however, it precludes the need for postoperative radiation and minimizes the chance of local recurrence. The following description presumes that there is a purely intraosseous destructive lesion in the proximal humerus and can be modified depending on the anatomic location and extent of any associated soft tissue mass. In general, involvement of the glenoid with metastatic disease is rare, and this section focuses on resection and reconstruction of only the proximal humerus with placement of a humeral head only without a glenoid component.

Develop wide medial and lateral subcutaneous flaps. Expose the deltopectoral interval. If the cephalic vein is maintained, it can be retracted medially or laterally with the deltoid (author prefers laterally). The pectoralis insertion is identified on the humerus, released, and tagged with a cuff of tendon maintained. The deltoid is retracted laterally, and its insertion on the humerus is detached and tagged. Sometimes a portion

of this attachment can be maintained for shorter humeral resections. For patients with an extensive proximal soft tissue mass, the deltoid can be released from the clavicle and acromion as far as the lateral acromion to increase exposure. The anterior humeral circumflex vessels are ligated and tied. This may cause some devascularization of the anterior deltoid, but it usually maintains viability with collateral flow. The conjoined tendon (short head of the biceps and coracobrachialis) originates at the coracoid process and is gently retracted medially. Do not abduct the arm or this will pull the axillary sheath toward the coracoid process. The musculocutaneous nerve is most likely to be injured if dissection occurs in this position. If additional exposure is necessary, the short head of the biceps and coracobrachialis are detached with a cuff of tendon and tagged. If the coracoacromial ligament can be maintained, it will help prevent superior subluxation of the humeral prosthesis. The teres major and latissimus dorsi are released from the humerus and tagged. The subscapularis is released from the humerus and tagged. Beware the axillary nerve as it exits through the quadrangular space inferior to the subscapularis. The long head of the biceps is identified and released distal to its origin on the glenoid and tagged.

of this attachment can be maintained for shorter humeral resections. For patients with an extensive proximal soft tissue mass, the deltoid can be released from the clavicle and acromion as far as the lateral acromion to increase exposure. The anterior humeral circumflex vessels are ligated and tied. This may cause some devascularization of the anterior deltoid, but it usually maintains viability with collateral flow. The conjoined tendon (short head of the biceps and coracobrachialis) originates at the coracoid process and is gently retracted medially. Do not abduct the arm or this will pull the axillary sheath toward the coracoid process. The musculocutaneous nerve is most likely to be injured if dissection occurs in this position. If additional exposure is necessary, the short head of the biceps and coracobrachialis are detached with a cuff of tendon and tagged. If the coracoacromial ligament can be maintained, it will help prevent superior subluxation of the humeral prosthesis. The teres major and latissimus dorsi are released from the humerus and tagged. The subscapularis is released from the humerus and tagged. Beware the axillary nerve as it exits through the quadrangular space inferior to the subscapularis. The long head of the biceps is identified and released distal to its origin on the glenoid and tagged.

The planned transaction of the humerus is marked and circumferential subperiosteal dissection is performed at this level. Maintain as much biceps and brachialis as possible in the setting of metastatic disease. Identify and protect the radial nerve within the spiral groove. At this point, the remaining proximal dissection can be completed (shoulder capsule, rotator cuff) or the humerus can be cut and elevated from the wound (author prefers the latter). Prior to humeral transection, the anterior cortex should be marked with an osteotome and marking pen to allow appropriate rotational placement of the prosthesis. Next, the triceps are released posteriorly. Proximally, the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor are released as close as possible to the greater tuberosity and tagged with long sutures as they will retract. The shoulder joint capsule is incised as close as possible to the humeral head and neck to facilitate a stable soft tissue reconstruction. The proximal humerus is then delivered from the wound with careful dissection of the axillary nerve and posterior humeral circumflex vessels posteriorly. A distal marrow margin can be checked by frozen section if a wide resection is planned.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree