Shoulder Pain

Dennis W. Boulware

|

A 26-year-old man presents with a 10-day history of right shoulder and upper arm pain, worse with lifting his arm over his head and interfering with sleep as he cannot find a position of comfort. He has tried rest and acetaminophen without relief. No trauma or precipitating event is recollected, but he had recently completed re-painting his bedroom over the weekend, 2 weeks ago.

Clinical Presentation

Shoulder pain is one of the most common complaints seen in a primary care setting especially with elderly patients. Most causes of shoulder pain are due to soft tissue periarticular problems such as rotator cuff impingement or injury, bursitis, and/or an adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) as opposed to glenohumeral arthritis. The clinical context of the shoulder pain often provides insight into the source of the problem such as a history of a systemic inflammatory or degenerative condition, repetitive use, or recent injury. This chapter addresses the clinical setting of nontraumatic isolated shoulder pain, and for a discussion of shoulder pain due to systemic or generalized diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, or osteoarthritis, the reader should refer to those specific chapters.

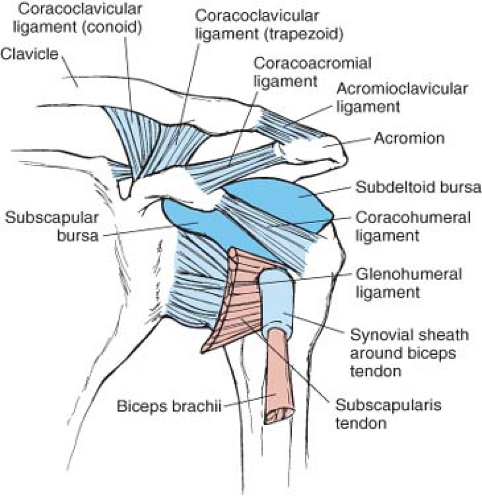

Most causes of shoulder pain can be attributed to soft-tissue structures surrounding the glenohumeral joint, as opposed to those originating from glenohumeral arthritis. An understanding of the anatomy and biomechanics of the shoulder, coupled with a focused physical examination to localize the anatomic source of pain, typically provides the clinician with an accurate diagnosis (Fig. 4.1). Proper and effective management can be implemented only after the source of the pain is identified accurately.

The shoulder is the most flexible and mobile joint in the body. This mobility is achieved by having a bony ball-and-socket joint with a large ball and a relatively small socket. This relatively unstable arrangement is made secure by the surrounding extra-articular structures including the various ligaments, labrum, rotator cuff, bicipital tendon, deltoid muscles, and so on. Typically, shoulder pain is due to dysfunction or disruption of the supporting soft-tissue structures, as opposed to glenohumeral arthritis. The most commonly involved structures causing shoulder pain are the rotator cuff, the subacromial bursa, the bicipital tendon, and the synovial capsule.

The first step in evaluating the patient is to confirm that they are describing a shoulder joint pain or a joint-related problem as they often refer to pain in the trapezius muscle as “shoulder pain.” Pain from the shoulder joint or its related periarticular structures is felt in the area over the deltoid muscle or

the upper brachium. Pain described in the trapezius muscle is likely due to trapezius muscle strain or referred from the cervical spine. If the patient confirms that the pain is localized to the deltoid area and/or the upper brachium, then proceed with an evaluation of the shoulder joint and its periarticular structures.

the upper brachium. Pain described in the trapezius muscle is likely due to trapezius muscle strain or referred from the cervical spine. If the patient confirms that the pain is localized to the deltoid area and/or the upper brachium, then proceed with an evaluation of the shoulder joint and its periarticular structures.

Historical qualities regarding severity or quality of pain are limited in identifying the cause of pain, whereas precipitating and alleviating factors, recent repetitive nonroutine activities (house painting, wallpaper hanging, etc.), and/or injuries can provide some insight. Shoulder pain precipitated by use is the most common presenting complaint and certain uses of the affected arm can be helpful. The rotator cuff is typically affected in the external rotators, especially the supraspinatus. Pain felt with forward flexion, abduction, or active external rotation of the shoulder typically suggests involvement of the rotator cuff. Pain on abduction, but not on external rotation or forward flexion of the shoulder suggests the subacromial bursa as the cause of pain. Nocturnal pain during sleep and the inability to find a restful recumbent position in bed are also common complaints of a rotator cuff problem or the subacromial bursa.

Clinical Points

Shoulder pain is often due to a soft tissue cause such as tendonitis or bursitis, rather than arthritis.

The physical examination of the shoulder is essential in identifying the cause.

The pain frequently radiates into the brachium.

Exploring recent overuse or trauma may help identify the cause.

When examination of the shoulder is fruitless in identifying a cause, consider referred pain from a cervical radiculopathy.

Examination

The physical examination of the shoulder is critical in identifying the cause and managing shoulder pain. A systematic routine examination of the shoulder will help the clinician identify the cause of the shoulder pain quickly and effectively. The examination will focus on the range of passive motion in rotation, abduction, and forward flexion as well as provocative maneuvers to attempt to reproduce the pain by active motion, palpation, or resistance. Tenderness present on active motion that is absent on the same motion passively usually suggests a tendinitis as the pain is elicited when tension is placed on the tendon. Typically, the patient will be guarding the painful shoulder voluntarily or involuntarily and the examination will be

insightful only if the patient is relaxed and cooperative. The prudent clinician will examine the non-tender shoulder first to prepare the patient for examination of the painful shoulder.

insightful only if the patient is relaxed and cooperative. The prudent clinician will examine the non-tender shoulder first to prepare the patient for examination of the painful shoulder.

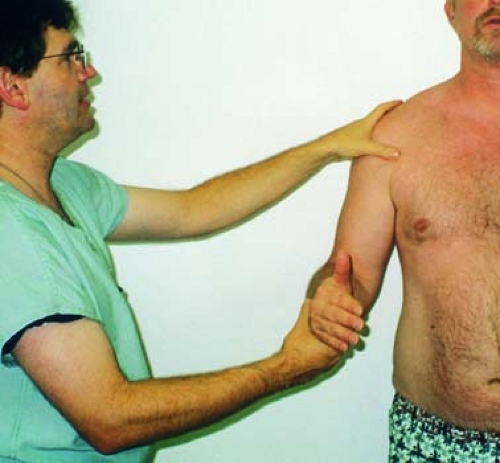

Figure 4.2 Measuring passive rotation. From Berg D, Worzala K. Atlas of Adult Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. |

Figure 4.3 Measuring passive glenohumeral abduction and forward flexion. From Berg D, Worzala K. Atlas of Adult Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. |

Start the examination with the patient sitting on the examination table in front of you. Passively flex the elbow to 90 degrees with the patient’s elbow to their side and gently use the forearm to rotate the shoulder joint internally, as it typically will not precipitate tenderness and will aid in gaining the patient’s confidence, and then test for external rotation (Fig. 4.2). Passive internal rotation to 90 degrees and passive external rotation to 90 degrees are normal, and is typically painless but diminishes slightly with age. Internal rotation is rarely tender or limited, but decreased passive external rotation will suggest structural barriers to full passive motion including bony and soft tissue structures. Osteophytes from degenerative joint disease or a contracted joint capsule from adhesive capsulitis, or a frozen shoulder, are common causes and will require imaging studies to differentiate. Non-tender decreased passive rotation may indicate the later stages of adhesive capsulitis or stable degenerative joint disease. Tenderness on passive external rotation only may indicate an active adhesive capsulitis or active osteoarthritis, whereas tenderness on passive internal and external rotations can suggest active synovitis from infectious or inflammatory causes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree