Low Back Pain and Lumbar Stenosis

Lisa L. Willett

|

A 62-year-old female presents with complaints of lower back pain and numbness in her feet, intermittently for 8 months. Pain is worse at the end of day and gets better with recumbency; pain is also more noticeable with ambulation and gets better when no longer walking. There is no history of fever, chills, and weight loss. There is no history of trauma or an unusual activity that preceded the onset of these symptoms. There is no history of malignancy or intravenous drug use.

Clinical Presentation

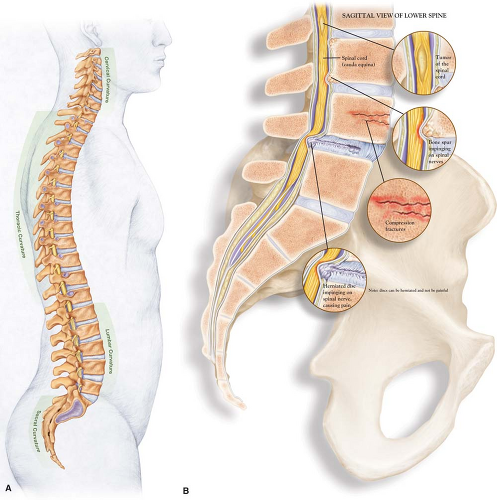

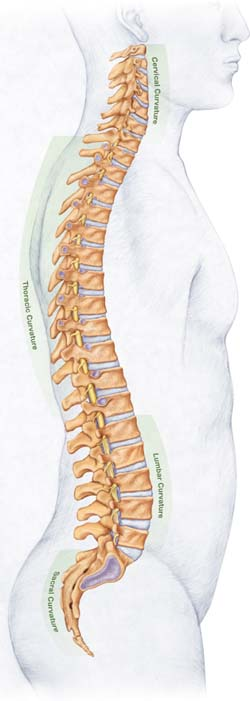

Low back pain is one of the most common reasons that patients seek medical attention. It is estimated that two thirds of adults have experienced low back pain at least once, and approximately 7% have had at least one severe episode within a 1 year period. The typical age of onset of low back pain is between 30 and 50 years, with men and women being equally affected (1,2). Low back pain originates from many spinal structures, and includes ligament strain, degeneration of facet joints, herniated discs, and spinal stenosis (Figs. 3.1A, 3.1B). Symptoms range from mild, self-limiting pain, to severe, incapacitating pain with radicular symptoms, neurologic compromise, and chronic morbidity.

Because of the complexity of the spine anatomy, a precise anatomical diagnosis for patients with low back pain is difficult. It is estimated that only 15% of patients with low back pain are able to be diagnosed with a precise spinal abnormality or specific etiology (1). In an effort to achieve accurate diagnosis and effective therapy, costly imaging and surgical referral is pursued. Despite wide variations in the clinical evaluation and management of low back pain, overall outcomes are similar for patients. Published guidelines exist to guide the clinician on the best approach to evaluate and manage acute and chronic low back pain in the primary care setting.

Clinical Points

Patients with low back pain should be classified into a risk category based on nonspecific low back pain, pain associated with radiculopathy (including herniated disc or spinal stenosis), and pain associated with systemic disease.

Motor weakness, fecal incontinence, and urinary retention are symptoms of cauda equina syndrome and require immediate surgical evaluation.

Patients with psychosocial stressors are more likely to develop chronic pain.

When taking the medical history, clinicians should attempt to place the patient into a category of risk (2). The three areas of risk are: (a) nonspecific low back pain, (b) pain associated with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis, and (c) pain from a systemic cause. In addition to the pain location, severity, and duration, a prior history of back pain and the clinical course is also important. The first priority is to rule out neurologic compromise. Questions should include the presence of lower extremity motor weakness, fecal incontinence, and urinary retention with overflow incontinence. Of these, urinary retention is the most frequent symptom of cauda equina syndrome.

The next level of questions should evaluate for systematic diseases, especially cancer with spinal metastasis, fractures from osteoporosis or steroid use, and spinal infections. Risk factors for cancer, including multiple myeloma,

include the following: age >50 years, a history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, night time pain or pain worsened with recumbent positions, and pain >6 weeks in duration. Risk factors for infection include fever, unexplained weight loss, history of intravenous drug use, indwelling catheters, recent infections, and history of bacteremia.

include the following: age >50 years, a history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, night time pain or pain worsened with recumbent positions, and pain >6 weeks in duration. Risk factors for infection include fever, unexplained weight loss, history of intravenous drug use, indwelling catheters, recent infections, and history of bacteremia.

Of patients who present to primary care with low back pain, spinal stenosis and symptomatic herniated discs account for 3% and 4%, respectively (2). Patients present with neurogenic claudication, or sciatica, the latter being defined as back pain radiating into the buttock and lower leg in a lumbar nerve root distribution. Patients with spinal stenosis are typically over the

age of 60 years and have a history of chronic low back pain for months to years. The pain is worse with walking or standing, improved with bending forward, and, at times, induced when bending backward (3,4). In a study of patients presenting to an orthopedic surgeon with pain or numbness in the legs, the most specific symptoms for lumbar spinal stenosis were a history of urinary symptoms, improvement with bending forward, and bilateral plantar numbness (5). Herniated lumbar discs can also present with sciatica, but can be distinguished from spinal stenosis by an acute onset of pain and examination features, such as a positive straight leg-raising, which is suggestive of a herniated disc.

age of 60 years and have a history of chronic low back pain for months to years. The pain is worse with walking or standing, improved with bending forward, and, at times, induced when bending backward (3,4). In a study of patients presenting to an orthopedic surgeon with pain or numbness in the legs, the most specific symptoms for lumbar spinal stenosis were a history of urinary symptoms, improvement with bending forward, and bilateral plantar numbness (5). Herniated lumbar discs can also present with sciatica, but can be distinguished from spinal stenosis by an acute onset of pain and examination features, such as a positive straight leg-raising, which is suggestive of a herniated disc.

Physical examination should evaluate for fever, vertebral tenderness, and neurologic deficits

Radicular symptoms are seen with herniated discs or spinal stenosis

Herniated discs cause acute severe back pain, involve L4/L5 and L5/S1, and have a positive straight leg-raising test

Spinal stenosis occurs in elderly patients with a history of chronic low back pain, worse with walking or standing, improved with bending forward, induced when bending backward, and has bilateral plantar numbness

Finally, assessment of psychosocial distress is important. Patients with depression, somatization disorder, substance abuse, job dissatisfaction or disability compensation, and those involved in litigation are more likely to have prolonged back pain and persistent unexplained symptoms (5).

Examination

As with the history, the physical examination for patients with low back pain should focus on the neurologic examination and should ensure that there are no deficits. After assessing for fever and the presence of vertebral tenderness with palpation, a focused neurologic examination should be performed. More than 90% of herniated discs occur at the L4/L5 and L5/S1 levels and the neurologic examination focuses on these nerve roots, and includes the straight leg-raising test (Fig. 3.2), and the motor and sensory function tests (2).

A straight leg-raising test involves having the patient supine on the examination table. The examiner holds the leg straight with one hand and cups the heel with the other. The straight leg is lifted off the examination table from the heel in an effort to reproduce the patient’s sciatica. A positive test produces pain that radiates below the knee between 30 and 70 degrees of elevation. A positive test on the ipsilateral side has a sensitivity of approximately 90% for a herniated disc, whereas a positive test when the opposite leg is raised (a crossed test) has a specificity of approaching 90% (2). Further neurologic evaluation includes sensory and motor findings of the L4 through S1 nerve root, and includes assessing knee strength and reflexes (L4), great toe and foot dorsiflexion (L5), foot plantar flexion and ankle reflexes (S1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree