Fibromyalgia

Graciela S. Alarcón

|

A 40-year-old obese, sedentary, Caucasian woman presents to a rheumatologist with a 6-month history of generalized myalgias, arthralgias, swelling of small hand joints, and morning stiffness of unspecified duration. Her primary care physician had run some tests and referred her for possible rheumatoid arthritis (RA). (IgM rheumatoid factor was positive at 24 units.) Other symptoms elicited by the rheumatologist included fatigue, unrefreshed sleep, intermittent abdominal pain, and increased urinary frequency. Morning stiffness lasted about 30 minutes. Physical examination revealed an obese white woman in no distress. There were multiple tender areas over the upper and lower back, and around the shoulder and pelvic girdles. The hands were puffy (fat), but no synovitis was detected in any of the joints. A complete blood count and a urinalysis were normal. Radiographs of the affected areas were not obtained.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a condition affecting preferentially middle-aged white women; men, children of either gender, and older adults can be affected, however (1). Fibromyalgia has been recognized primarily in the middle and upper socioeconomic strata. Whether this reflects only access to health care or true differences in the incidence and prevalence of the disorder among disadvantaged populations has not been determined.

The true incidence and prevalence of FM is unknown. Population-based studies are difficult to interpret; issues such as the criteria used to diagnose FM, whether primary and secondary cases are included, and the demographic characteristics of the population that is being surveyed need to be considered. Studies from North America and Europe, imperfect as they may be, reveal overall prevalence rates between 1% and 5%, but figures as high as 13% have been reported. These population-based studies confirm the gender distribution (predominantly female) of the FM syndrome. In the clinical setting, the frequency of FM depends, to a certain extent, on the degree of awareness about this condition. Figures between 2% and 4% have been reported in the primary care setting. In rheumatology clinics, the frequency of FM fluctuates between 3% and 20%. These figures probably reflect the rheumatologists’ interest in FM and the level of awareness about this condition among community physicians and the public at large (1).

Like many other rheumatic disorders, the etiopathogenesis of FM is probably multifactorial (1). Susceptible individuals may develop FM as a result of the

interaction of peripheral and central factors. Familial aggregation of FM does not itself prove genetic susceptibility; in fact, it can be argued that familial aggregation reflects only learned behavior among the offspring of adult patients with FM. However, the familial pattern of FM (affecting primarily the female gender) suggests an autosomal-dominant transmission (1). Animal data indeed suggest that genetic factors may influence pain sensitivity and pain modulation; human data are just emerging (1).

interaction of peripheral and central factors. Familial aggregation of FM does not itself prove genetic susceptibility; in fact, it can be argued that familial aggregation reflects only learned behavior among the offspring of adult patients with FM. However, the familial pattern of FM (affecting primarily the female gender) suggests an autosomal-dominant transmission (1). Animal data indeed suggest that genetic factors may influence pain sensitivity and pain modulation; human data are just emerging (1).

Clinical Points

Fibromyalgia is probably more common than rheumatoid arthritis. In the absence of synovitis, a positive rheumatoid factor test should not be considered to diagnose RA.

Women are more commonly affected. It occurs mainly in adults, but can affect children and the elderly.

Newer criteria developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) do not include the classical tender points.

In some patients, FM evolves in an insidious manner. It is impossible to determine precisely when symptoms really started. Other patients, however, can time the onset of their symptoms to a traumatic event (physical or emotional) or to a well-defined infectious process. In fact, these postinfectious cases were called in the past “reactive FM” (comparing them to other postinfectious rheumatic disorders (reactive arthritis)) (1), but this term is no longer used. With regard to trauma, the nature of the trauma does not really matter (severity of injury or even if the event was predominantly physical, but perceived as emotional by the patient) (1). Numerous infectious processes have been described as capable of precipitating FM. They include infections with the human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, Coxsackie virus, and Parvovirus B19 (1). Infections with Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) have also been recognized as capable of precipitating FM. It should be noted that, unfortunately, many cases of post-Lyme FM are erroneously diagnosed as chronic Lyme disease and patients are subjected to costly, unnecessary, and lengthy treatments (see Chapters 27 to 30).

Clinical Presentation

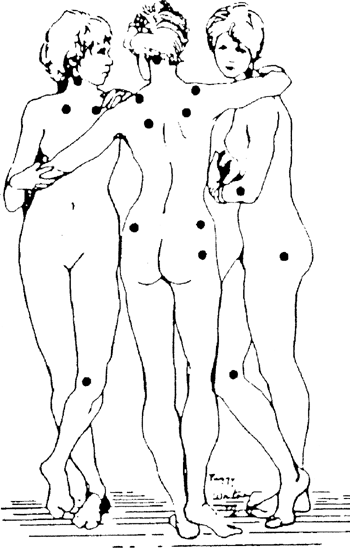

Fibromyalgia is a chronic musculoskeletal disorder characterized by generalized pain and tenderness at specific anatomic sites, called tender points (1).

Fibromyalgia can occur in isolation or in the setting of other musculoskeletal or rheumatic disorder (primary vs. secondary FM) (1). In fact, in some patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the overwhelming clinical manifestations are those of FM, and not the ones we typically attribute to either RA or SLE. These FM symptoms are, by and large, unresponsive to therapies commonly used for the treatment of the underlying condition.

Musculoskeletal Manifestations

Patients with FM often present to their physicians complaining of diffuse arthralgias and myalgias as well as of joint swelling, particularly in the small joints of the hands and feet (1). Some patients also complain of morning stiffness, lasting from minutes to hours; others exhibit joint hypermobility. It should be noted, however, that joint swelling is not present in these patients.

The diagnosis is clinical. A complete history and a physical examination are necessary. Multiple tender points are usually present, whereas joint swelling is conspicuously absent.

Extensive (and expensive) ancillary tests are not recommended.

Treatment is multidisciplinary with medications being only one element.

Other Clinical Manifestations

Patients with FM may experience numerous other clinical manifestations. In fact, these other manifestations may be the ones that bring these patients to seek medical help. Symptoms referred to all organ systems have been described. In some cases, these other manifestations, rather than pain, may be the predominant ones.

Fatigue

Patients with FM often complain of some degree of fatigue; rarely, however, is fatigue so intense as to be the factor determining incapacitation, unlike the situation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (1). In turn, patients

with CFS may experience arthralgias and myalgias, and may exhibit some tender points. Rarely, the patients may meet criteria for both the disorders. Like pain, fatigue is a subjective manifestation, which can only be quantified by self-report.

with CFS may experience arthralgias and myalgias, and may exhibit some tender points. Rarely, the patients may meet criteria for both the disorders. Like pain, fatigue is a subjective manifestation, which can only be quantified by self-report.

Sleep Disturbances

Patients with FM, regardless of the intensity of their pain, usually complain of poor sleep; they may have difficulty falling asleep or may wake up throughout the night. As a result, they awake in the morning unrefreshed and tired. Some investigators have postulated that the musculoskeletal pain in FM results from sleep deprivation. Sleep studies conducted in patients with FM have indeed shown abnormal recordings during deep sleep. This pattern, called “non–rapid eye movement anomaly,” is characterized by a relative fast frequency (alpha waves) superimposed in a slower delta frequency (1). Similar findings have been obtained in normal individuals subjected to sleep deprivation; these abnormalities are neither specific nor sensitive for FM. Another abnormality, sleep apnea, described in some patients with FM, primarily overweight men, can be considered a marker for this disorder. However, only a careful assessment of sleep (including the spouse or bed partner) may uncover the presence and severity of sleep apnea.

Other Manifestations

Table 17.1 provides other clinical manifestations described in patients with FM. These patients may be under the care of different physicians for their various symptoms and may be subjected to extensive, expensive, and even invasive tests and procedures in order to rule out more serious or different disorders. Imaging and nuclear medicine studies, endoscopies, and exploratory surgeries are, unfortunately, not uncommonly performed. Table 17.1 provides procedures and tests commonly obtained in patients with FM.

Rheumatologists see patients with possible FM in consultation in different situations. One scenario is that of patients with FM who have failed numerous treatments and who come seeking a cure for their ailment. A second scenario is that of patients who want to legitimize their diagnosis for legal purposes (e.g., workman’s compensation or disability determination) (1). Still others are patients with different musculoskeletal disorders, who had been diagnosed as having FM but whose diagnoses have been overlooked. Examples include spinal stenosis, peripheral neuropathies, systemic vasculitis, myositis, and polymyalgia rheumatica, among others. A fourth scenario is that of patients who have been diagnosed as having “refractory RA” and have received multiple medications, but have significant joint complaints (pain primarily). If patients are obese, the differentiation between puffy or fatty hands and true arthritis may not be readily evident to the nonrheumatologist. Lastly, other patients have been diagnosed as having SLE or referred for evaluation of possible SLE. They present FM-like manifestations and a positive test for antinuclear antibodies (ANA). They may also have subjective, but not objective, clinical manifestations that render the diagnosis of SLE plausible, until the history is examined more critically (1). For example, patients may present after having had oral or nasal ulcers, photosensitivity, and photosensitive rashes. Similarly, they may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon–like manifestations, alopecia, chest pain (which worsens in inspiration), and of course, arthralgias and myalgias. A positive ANA in this setting reinforces the diagnosis of SLE and, unfortunately, may prompt the initiation of potentially toxic pharmacologic compounds. Although it is never possible to be sure whether such patients may eventually develop SLE, it is preferable to wait until objective evidence of SLE becomes evident and to not alarm these patients unduly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree