Rheumatoid Arthritis, Including Sjögren’s Syndrome

Zachary M. Pruhs

James R. O’Dell

Ted R. Mikuls

|

A 45-year-old woman presents with 4 months of worsening pain and stiffness in her finger joints, wrists, and balls of the feet bilaterally. Her symptoms are worse in the morning, improve with activity, and are associated with occasional warmth and swelling of the hands. Hand radiographs show periarticular erosions and osteopenia (Fig. 9.1).

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic inflammatory disease with its primary manifestation in the synovium. The hallmark of the disease is a chronic, symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) that typically affects the hands, wrists, and feet initially and later may involve any synovial joint. Although RA primarily involves the synovium, features of systemic disease are present in almost all patients and range in severity from fatigue to severe multisystem vasculitis. In recent years, significant advances in therapy have occurred, however, RA continues to result in substantial morbidity for most patients. RA patients have a higher mortality rate than the general population that is primarily related to increased cardiovascular disease burden.

Epidemiology

RA affects all racial groups worldwide and while it is seen more commonly in some populations, the prevalence in most cohorts is estimated to be 0.5% to 1%. In the developed world there appears to be a trend toward decreasing RA incidence and prevalence since the 1960s. Overall, RA is two to three times more prevalent in women than in men. A study in Minnesota reported an incidence of 50/100,000 person-years in men and 98/100,000 person-years in women (1). The preponderance of women with new onset RA was most striking in the younger age groups, but nearly equal for patients >75 years of age. The incidence of

RA increases with age, with female excess in each age range found in most studies.

RA increases with age, with female excess in each age range found in most studies.

Gender and Hormonal Influences

The greatest differences in incidence rates between men and women are seen in patients below 50 years of age, where RA is relatively uncommon in men. Therefore, hormonal mechanisms are felt to play a part in RA risk. In the past, the use of oral contraceptive pills were thought to be protective in the development of RA and postpartum flares of RA are also well documented in addition to an ameliorating impact on disease during late-term pregnancy. More recent studies suggest that while longer periods of breastfeeding may protect from RA, neither parity nor use of oral contraceptive pills appears to decrease risk of disease. In a recent large cohort study, use of postmenopausal hormone therapy showed no significant improvements in either risk or severity of RA (2). Some have suggested that men with RA may have mild testosterone deficiencies, and replacement may result in some decrease in symptoms.

Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors

First-degree relatives of those with RA are at increased risk of developing the condition, with siblings of severely affected patients at highest risk. Monozygotic twins have a concordance rate of about 12% to 21%, whereas dizygotic twins have a rate about one quarter of this. Genetic predisposition varies widely with ethnicity and geography. While worldwide prevalence is estimated at ∼0.5% to 1%, Native Americans of the Pima and Chippewa tribes have an RA prevalence of 5.3% and 6.8% respectively, an increased disease burden thought to be mediated by increased genetic risk among these populations.

Select human leukocyte antigens (HLA) class II molecules represent the most important genetic risk factor in RA and the relationship extends across ethnic groups. There is extensive evidence linking a host of HLA-DRB1 variants (often called “shared epitope” or SE alleles) with increased susceptibility to anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody positive RA. Although not as strongly associated with disease risk as HLA-DRB1 SE containing alleles, several non-HLA genetic risk factors for disease susceptibility have now been defined including polymorphisms in PTPN22, STAT4, CTLA4, PADI4, and C-rel. However, genetic testing in RA (for either diagnostic or prognostic purposes) remains largely confined to research without widespread clinical application.

Of the many environmental factors linked to RA risk, cigarette smoking is perhaps the best documented. Smoking has been associated with a 50% to 70% increased risk of RA, a risk that is greatest among those carrying HLA-DRB1 SE containing alleles (a gene-environment interaction). Other factors reported to influence RA risk include occupational exposures (related to silica inhalation) and alcohol use, the latter reported to exert a protective effect.

Clinical Points

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a clinical diagnosis based primarily on a thorough history and physical exam aided by the select use of laboratory tests and imaging.

Patients with RA suffer from increased morbidity and mortality, the latter primarily due to an excess of cardiovascular disease.

The cornerstone of RA treatment is early aggressive therapy treating to a goal of low disease activity or remission to prevent permanent damage.

The ultimate goal of RA treatment is to achieve and maintain complete remission.

Long-term goals of RA treatment also include the prevention of disability and improved survival.

Immediate RA treatment goals include: decreasing pain, preventing joint damage and maintaining function, and controlling other symptoms of inflammation.

Clinical Presentation

The hallmark symptoms of RA include:

Stiffness—typically greater in the morning and relieved with activity.

Pain—often a chief complaint of the patients and frequently difficult to quantify.

Tenderness—palpation with a lateral joint squeeze will elicit pain in patients with active synovitis.

Swelling—results from synovial proliferation and is often most prominent at the small joints of the hands and feet.

Deformity—develops due to stretching of tendons and ligaments along with bony erosion and is typically irreversible.

Table 9.1 Extra-articular Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The diagnosis of RA should be considered in any patient with inflammatory arthritis, especially if the hands and feet are involved. The patient’s response to the question, “What is the worst time of day for your joints?” is often telling. Patients with inflammatory arthritis such as RA usually report significant morning stiffness (often lasting >1 hour), whereas patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and other mechanical syndromes are usually worse later in the day after activity. In addition, significant fatigue may be present even in early RA.

Extra-Articular Manifestations of Ra

Extra-articular manifestations of RA (ExRA) range in severity from nodular skin lesions to systemic vasculitis (Table 9.1). In a large cohort study over a 30-year time span, more than 40% of RA patients had extra-articular involvement with nearly 13% of those categorized as severe (3). The most frequent manifestations of ExRA were subcutaneous nodules found in 34% of patients. The most frequent severe manifestation of ExRA was pericarditis (5%). Predictors of severe ExRA include smoking at time of diagnosis, anti-CCP and RF positivity. Importantly, patients with ExRA have significantly increased morbidity and patients with severe ExRA have a markedly increased mortality.

Bilateral polyarticular inflammatory arthritis often confined to the hands and feet may be characteristic early in the disease course.

Inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP) may be normal at the time of presentation in one third to half of the patients.

Rheumatoid factor (RF) is positive in ∼70% of patients but is not specific; anti-CCP antibody has a similar sensitivity to RF but is highly specific (>95%) for RA.

Sjögren’s Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome is well recognized as an extra-articular manifestation of RA. Sjögren’s is a connective tissue disease affecting the exocrine glands characterized by dry eyes and mouth that is frequently associated with other connective tissue diseases including RA (4). Sjögren’s syndrome is often classified by whether it is primary (occurring in isolation) or secondary (occurring concomitantly with another rheumatic condition) with signs and symptoms that can be mimicked in select viral infections (e.g., Hepatitis C, HIV), lymphoproliferative malignancy, and sarcoidosis. The relationship between RA and Sjögren’s was first noted in 1933 by Henrik Sjögren himself. Patients suffering from Sjögren’s will often present with parotid and lacrimal gland swelling in addition to their symptomatic complaints.

Diagnosis may be aided by the Schirmer’s (assessing for ocular dryness) and Rose Bengal tests as well as salivary gland or lip biopsy; positive serologies for ANA, anti-SSA/SSB, and RF are characteristic of Sjögren’s syndrome. Sjögren’s may exhibit extraglandular involvement including visceral (heart, lungs, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, central/peripheral nervous system) and non-visceral (skin, muscles, joints) manifestations. Classification of the disease is guided by the revised rules for classification from the American–European Consensus Group (Table 9.2).

Examination

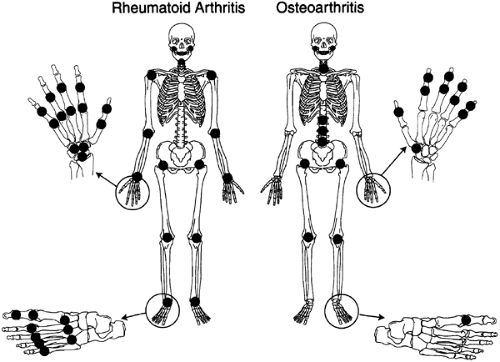

Joint distribution is critical in the diagnosis of RA. Initially, RA is often limited to the hands and feet. In the hands, the proximal interphalangeal joints (PIPs) and metacarpal phalangeal joints (MCPs) are most likely to be involved early in the disease course. Figure 9.2 compares and contrasts the joints most commonly involved in RA and OA. In the hand, the distal interphalangeal joints (DIPs) are characteristically involved in OA (Heberden nodes) but seldom involved in RA, the PIPs may be involved with either, whereas MCP involvement is the rule in RA and seldom occurs in OA. The wrist is frequently involved in RA, whereas only the first carpal–metacarpal joint is commonly involved in OA. A remarkable feature of RA is the symmetry of involvement.

If inflammation persists over time, permanent damage, including tendon, ligament, cartilage, and subchondral bone destruction can occur, with resultant joint deformity and disability. Although inflammation and deformity are most often seen initially in the hands and feet, the disease may later affect larger joints. Involvement of the knees, hips, and shoulders accounts for significant morbidity including work disability in a large percentage of patients. With early and effective treatments, deformity and severe disability are occurring less frequently.

Table 9.2 Revised International Classification Criteria for Sjögren’s | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Figure 9.4 Arthritis mutilans. From Koopman WJ, Moreland LW, eds. Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A Textbook of Rheumatology, 15th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005. |

Fingers

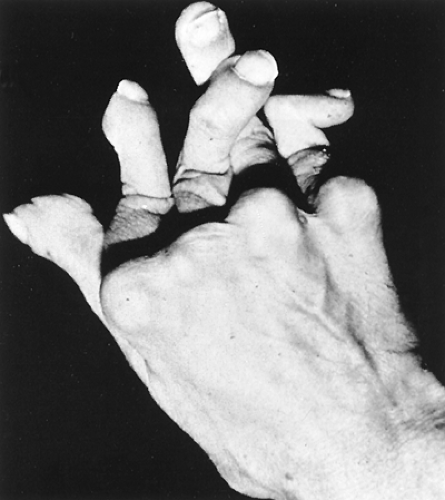

Non-reducible flexion contractures of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint with concomitant hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint of the finger known as “boutonniere” deformity may occur with progressive disease. Hyperextension at the proximal interphalangeal joint with flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint or “swan-neck” deformity is also seen in RA (Fig. 9.3). Although similar deformities can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), these are typically reducible (the so-called Jaccoud’s arthropathy). “Triggering” of the finger occurs when thickening or nodule formation of the tendon interacts with the concomitant tenosynovial proliferation, trapping the tendon (stenosing tenosynovitis). Tendon rupture may occur due to infiltrative synovitis in the digit or bony erosions that produce surfaces that cut the tendon at the wrist (especially the flexor pollicis longus). Arthritis mutilans (“opera glass hands”) results if destruction is severe and extensive, with dissolution of bone (Fig. 9.4).

Metacarpophalangeal Joints

Two typical deformities may occur at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints—volar or palmar subluxation of the fingers relative to the metacarpal bones and ulnar deviation (Fig. 9.5). Most cases of ulnar deviation are accompanied by radial deviation of the wrist, roughly proportional to the degree of ulnar deviation of the fingers. Although RA is the most common cause of ulnar deviation, other arthritides, as well as certain neurologic deficiencies, may result in ulnar deviation as well.

Wrists

The wrist is the site of multiple potential problems in patients with RA. The combination of ulnar drift of the

fingers and radial deviation of the wrist is known as a “zig-zag” deformity. Wrist subluxation may lead to rupture of the extensor tendons of the little, ring, and long fingers (Fig. 9.6), as the end of the distal ulna may be roughened secondary to erosion of bone and may abrade the tendons as they move back and forth during normal hand function. Entrapment of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel (carpal tunnel syndrome) leads to numbness and decreased sensation on the palmar aspect of the thumb, index, long, and radial aspect of the ring fingers, and later to weakness and atrophy of the muscles in the thenar eminence (Fig. 9.7).

fingers and radial deviation of the wrist is known as a “zig-zag” deformity. Wrist subluxation may lead to rupture of the extensor tendons of the little, ring, and long fingers (Fig. 9.6), as the end of the distal ulna may be roughened secondary to erosion of bone and may abrade the tendons as they move back and forth during normal hand function. Entrapment of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel (carpal tunnel syndrome) leads to numbness and decreased sensation on the palmar aspect of the thumb, index, long, and radial aspect of the ring fingers, and later to weakness and atrophy of the muscles in the thenar eminence (Fig. 9.7).

Figure 9.6 Radiograph showing wrist destruction and subluxation in a patient with RA. William J. Koopman, Larry W. Moreland, Arthritis and Allied Conditions: A Textbook of Rheumatology, 15th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|