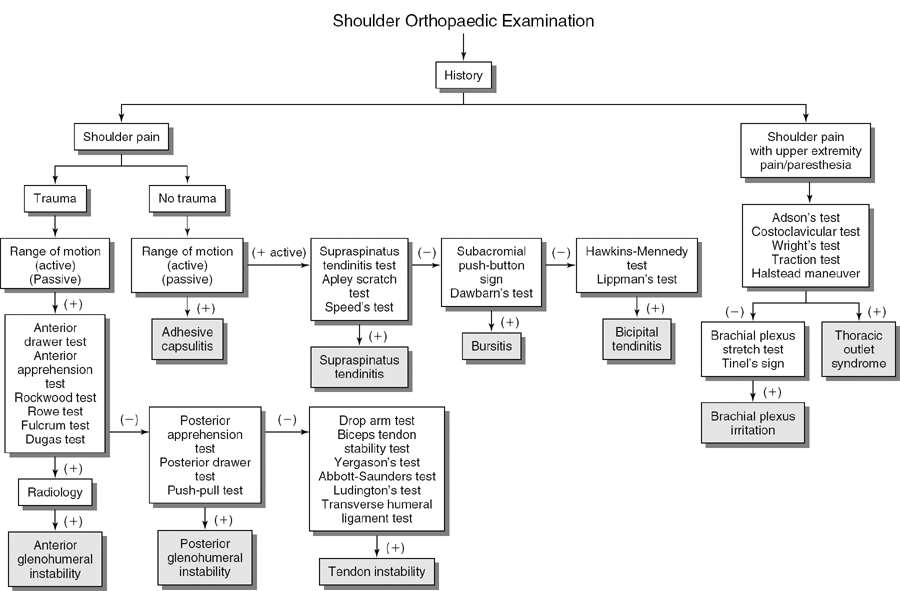

Shoulder Orthopaedic Tests

Shoulder Palpation

Anterior Aspect

Descriptive Anatomy

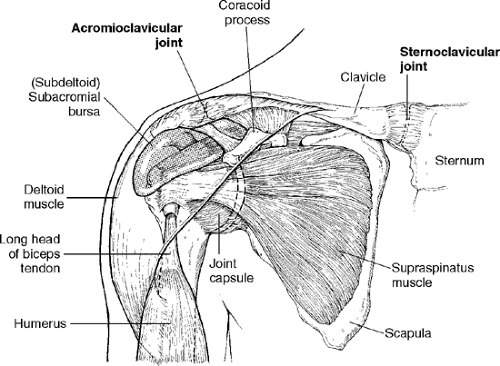

The clavicle is slightly anterior and inferior to the top of the shoulder. The sternoclavicular joint, which attaches the clavicle to the sternum, lies at the medial end of the clavicle. The acromioclavicular joint, which is lateral, attaches the clavicle to the acromion process of the scapula (Fig. 5-1).

Procedure

With your fingertips, palpate the length of the clavicle from the medial aspect at the sternoclavicular joint to the lateral aspect at the acromioclavicular joint (Fig. 5-2). Note any abnormal tenderness or bumps along the length of the clavicle that indicate a fracture secondary to recent trauma or a healed fracture with callus formation. Compare the clavicles for symmetry and placement. Next, palpate the sternoclavicular joint (Fig. 5-3) and acromioclavicular joint (Fig. 5-4) for tenderness with your index and middle fingers. If the affected clavicle and associated joint are more anterior, posterior, or superior than the other, suspect a subluxation or dislocation of the clavicle at the affected joint. Flexing and extending the shoulder during acromioclavicular joint palpation may reveal crepitus (Fig. 5-5). Crepitus is secondary to joint inflammation, such as osteoarthritis.

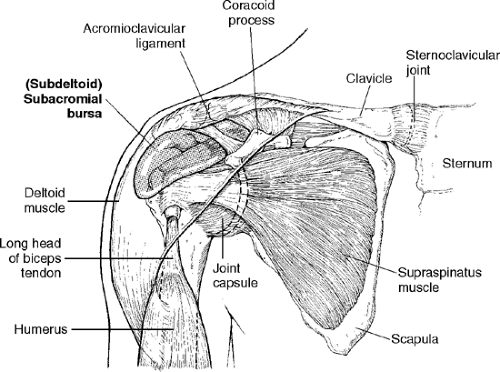

Descriptive Anatomy

The subacromial portion of the bursa is a fluid-filled sac that extends over the supraspinatus tendon and beneath the acromion process. The subdeltoid portion, beneath the deltoid muscle, (Fig. 5-6) separates the deltoid muscle from the rotator cuff.

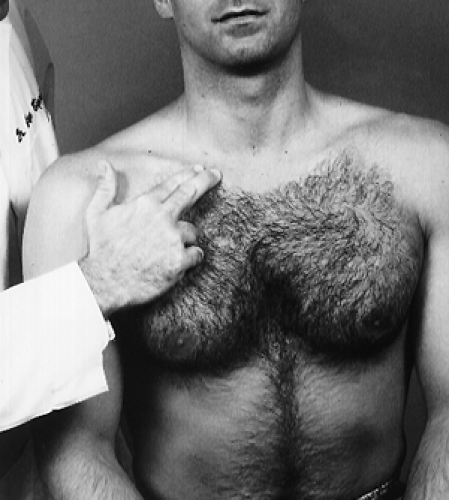

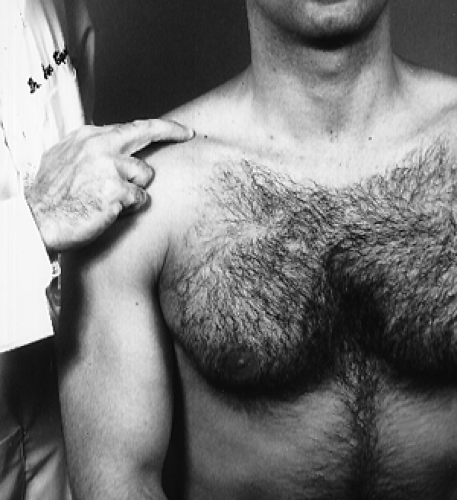

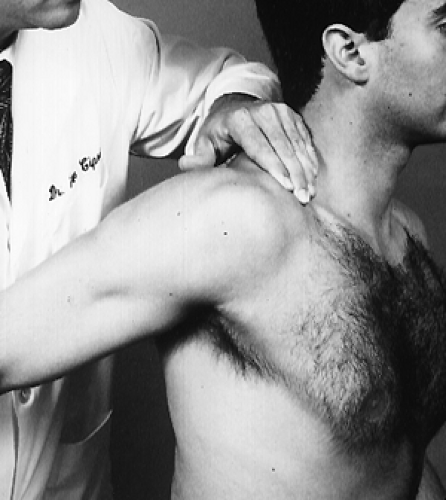

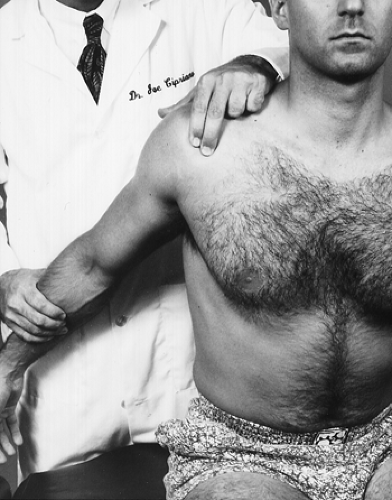

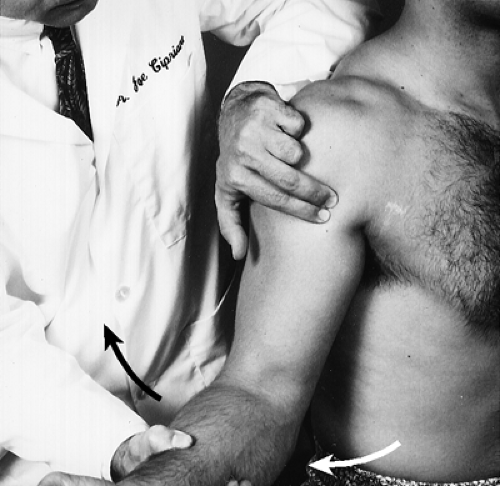

Procedure

With one hand, extend the patient’s arm. With your opposite hand, palpate for tenderness, masses, and thickening of both subacromial (Fig. 5-7) and subdeltoid (Fig. 5-8) portions of the bursa. Suspect subacromial or subdeltoid bursitis if the bursa is tender. Tenderness may also be associated with restriction of motion and crepitus of the shoulder, especially in abduction and forward flexion.

Descriptive Anatomy

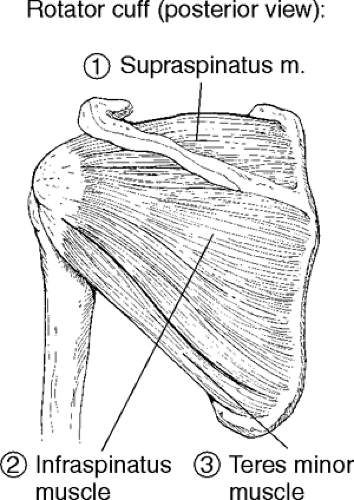

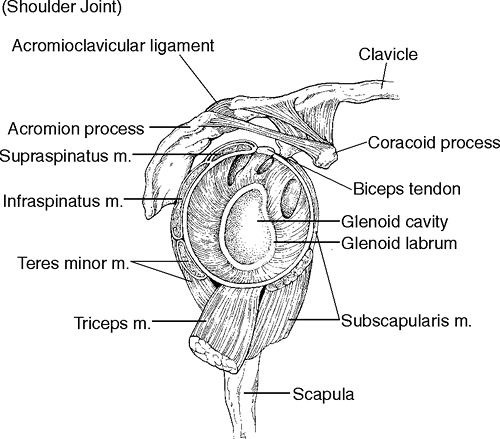

The rotator cuff is composed of four muscles, three that are palpable and one that is not. The three palpable muscles are the supraspinatus, which lies above the spine of the scapula and whose tendon lies under the acromion process; the infraspinatus, which lies inferior to the supraspinatus; and the teres minor, which is inferior to the infraspinatus (Figs. 5-9 and 5-10) The fourth muscle is the subscapularis, which is under the scapula and is difficult to palpate. The rotator cuff holds the humerus in the glenoid cavity and blends with the articular capsule to provide dynamic stabilization.

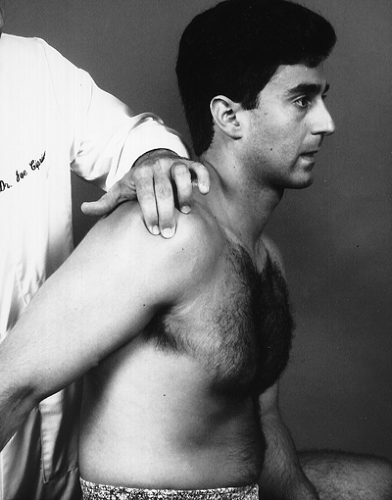

Procedure

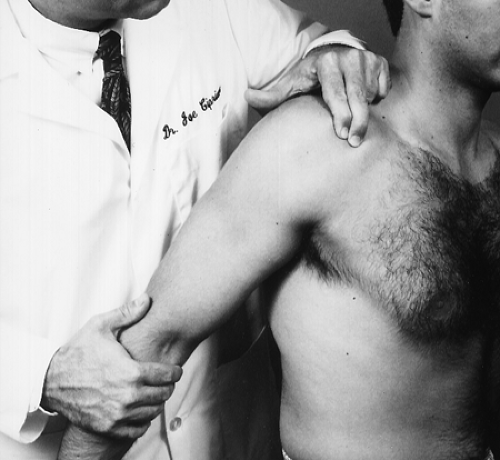

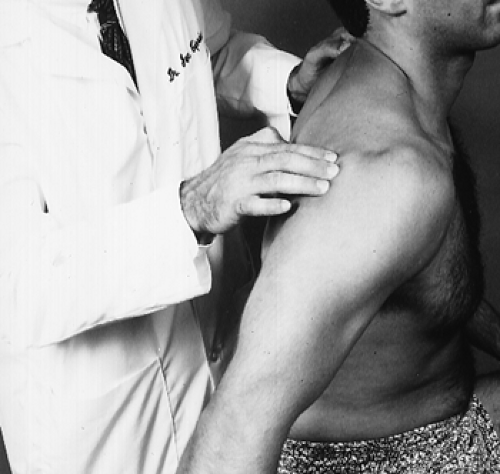

Sitting behind the patient, grasp the patient’s arm and extend it backward 20°. With your other hand, palpate inferior to the anterior border of the acromion process (Fig. 5-11). Note any tenderness, swelling, nodular masses, or gaps in the cuff. Tendinitis, tears, abnormal calcium deposits, and degeneration in the cuff may elicit tenderness and pain upon palpation. A palpable gap may indicate a ruptured tendon.

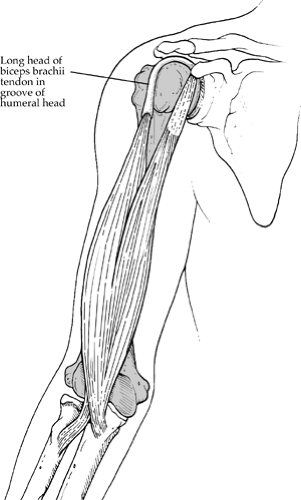

Descriptive Anatomy

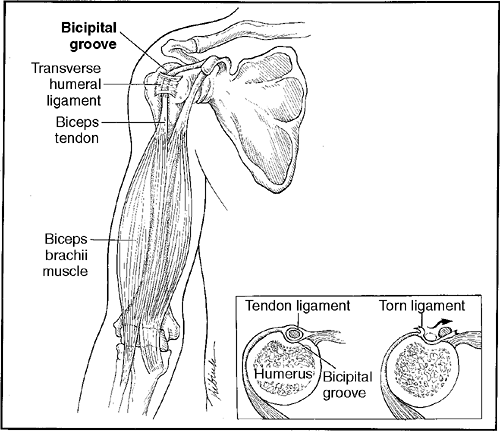

The bicipital groove is anterior and medial to the greater tuberosity of the humerus. The tendon of the long head of the biceps muscle and its synovial sheath lie in its groove. The transverse humeral ligament holds the tendon in place (Fig. 5-12).

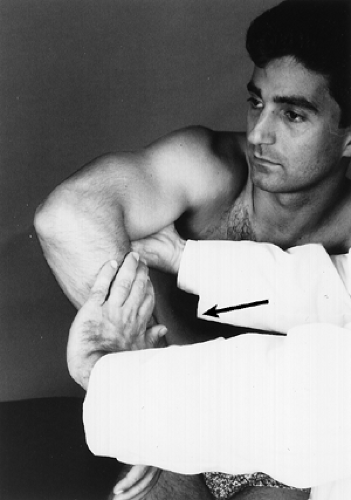

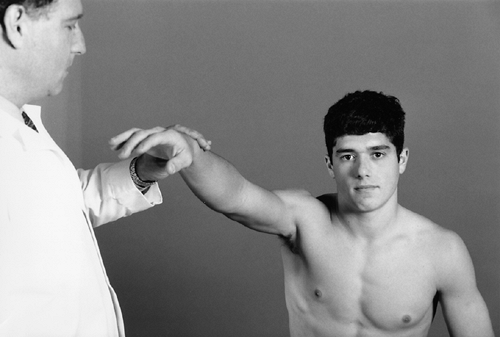

Procedure

With one hand, locate the inferior tip of the acromion process, then move inferiorly to the greater tuberosity of the humerus. With your other hand, grasp the patient’s arm and externally rotate it (Fig. 5-13). You will feel the bicipital groove slip under your fingers. Note any tenderness, which may indicate tenosynovitis of the bicipital tendon and its sheath. Also note any excessive movement of the tendon in its groove; it may indicate a predisposition of the tendon to dislocate out of the bicipital groove or a torn or ruptured transverse humeral ligament.

Descriptive Anatomy

The biceps muscle has two heads that originate from different areas. The long head originates from the tuberosity above the glenoid cavity, and the short head originates from the coracoid process of the scapula. They both insert into the bicipital tuberosity of the radius (Fig. 5-12).

Procedure

With the patient’s elbow flexed to 90°, begin palpating distally from the bicipital tuberosity of the radius upward to the bicipital groove (Fig. 5-14). Note any tenderness, spasm, or muscle mass. Tenderness at the proximal end may indicate tenosynovitis of the biceps tendon. Tenderness at the belly of the muscle may indicate muscle strain or an active trigger point. If a curling of the muscle secondary to overload is evident at the mid arm, suspect a rupture of the biceps tendon from its origin.

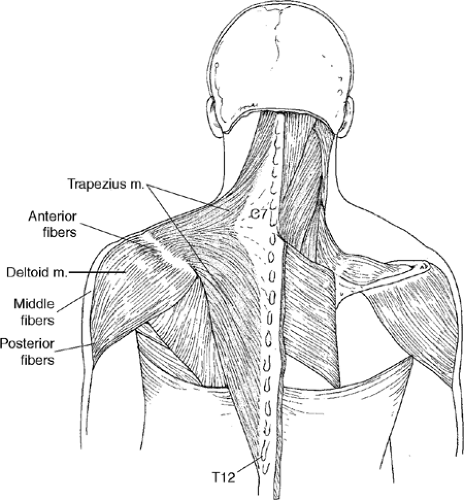

Descriptive Anatomy

The deltoid muscle originates from the clavicle and acromion process of the scapula and inserts into the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus (Fig. 5-15). The three parts of the fibers are the anterior, middle, and posterior. This muscle is capable of acting in parts or as a whole. The anterior part flexes and medially rotates the humerus. The middle part abducts the humerus. The posterior part extends and laterally rotates the humerus.

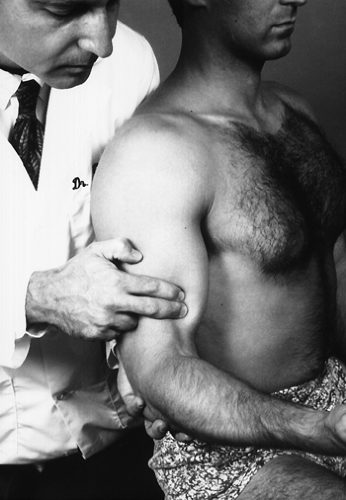

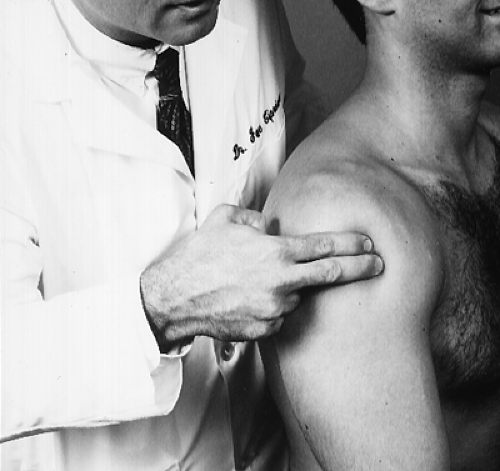

Procedure

Begin palpation of the anterior portion of the deltoid muscle from the acromion process inferiorly (Fig. 5-16), then from the lateral aspect of the shoulder (again inferiorly) for the middle part of the deltoid muscle (Fig. 5-17). Finally, palpate the posterior aspect of the deltoid muscle from the superior aspect to the inferior aspect with the patient’s shoulder extended (Fig. 5-18). Note any tenderness or taut muscle fibers. Tenderness at the lateral aspect of the deltoid is associated with subdeltoid bursitis. Tenderness at the anterior aspect of the deltoid may be associated with pathology or injury in the bicipital groove, because the anterior aspect of the deltoid muscle covers the groove and its tendon. General tenderness may indicate a strain or active trigger point of the deltoid muscle secondary to overuse, overload, trauma, or chilling.

Posterior Aspect

Descriptive Anatomy

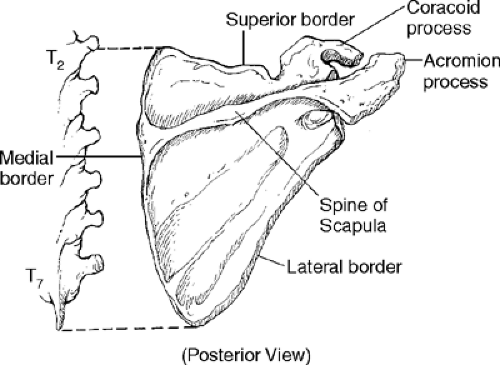

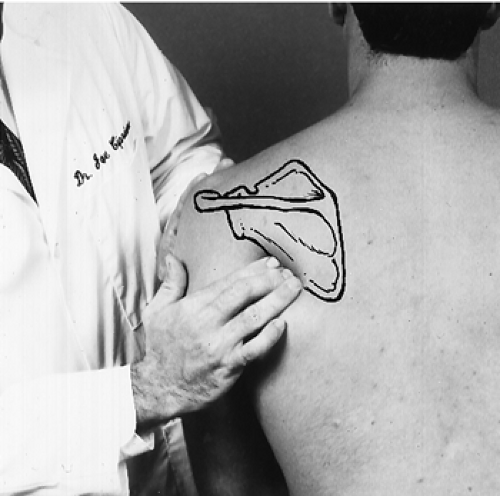

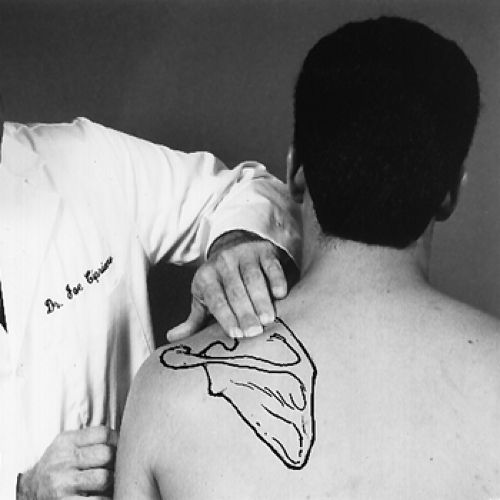

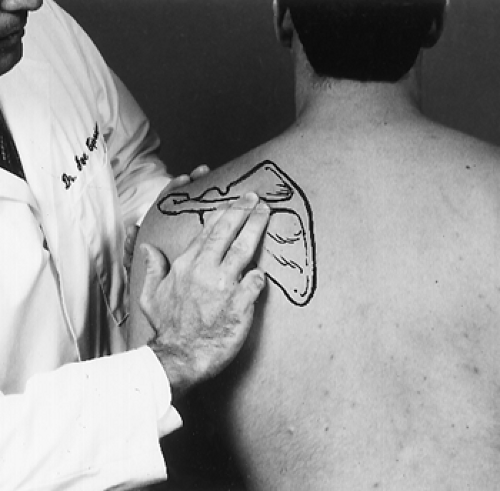

The scapula lies between T2 and T7. It has three borders, medial, lateral, and superior. It also has a sharp ridge that extends from the acromion process, which is the spine of the scapula (Fig. 5-19).

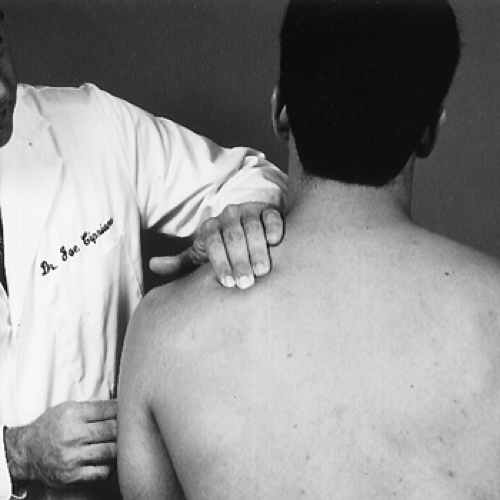

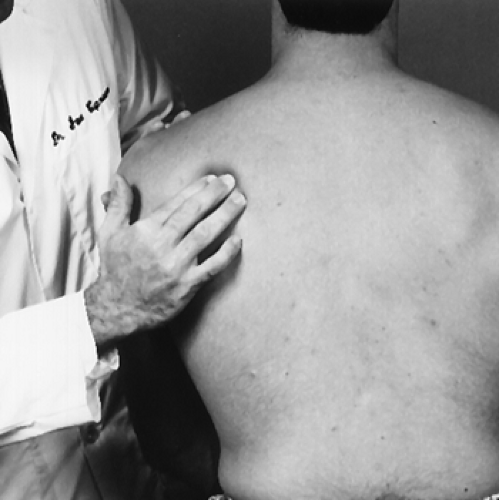

Procedure

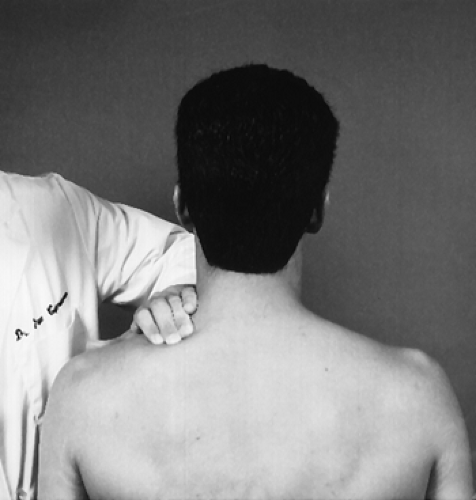

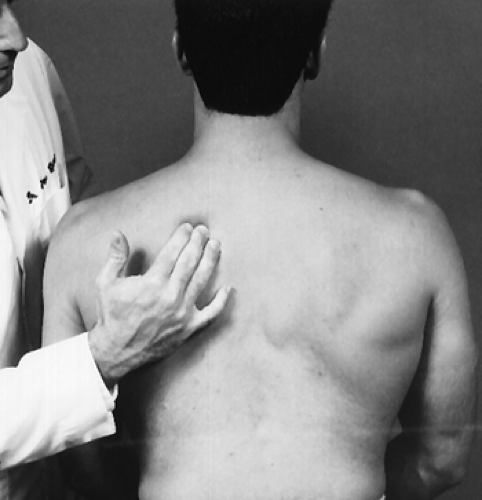

Starting with the medial border of the scapula, palpate all three borders, noting any tenderness (Figs. 5-20–5-22). Next, palpate the spine of the scapula, noting any tenderness and/or abnormality (Fig. 5-23). Finally, palpate the posterior surfaces above the spine of the scapula for the supraspinatus muscle (Fig. 5-24) and below the spine for the infraspinatus muscle (Fig. 5-25). Note any tenderness, palpable bands, atrophy, or spasm. Palpable bands in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle may indicate a myofascial syndrome caused by overuse, overload trauma, or chilling. Atrophy may indicate a disruption of the nerve supply to the suspected muscle.

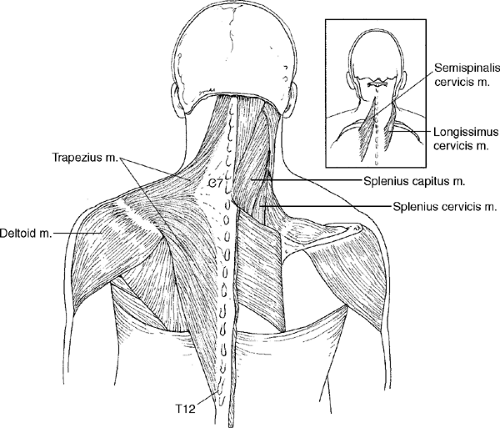

Descriptive Anatomy

The trapezius muscle originates from the occiput, ligamentum nuchae, and spine of C7 to T12 vertebra. It inserts into the acromion process and spine of the scapula (Fig. 5-26). The trapezius contains three sets of fibers that perform different actions. The superior fibers elevate the shoulders; the middle fibers retract the scapula; and the inferior fibers depress the scapula and lower the shoulders.

Procedure

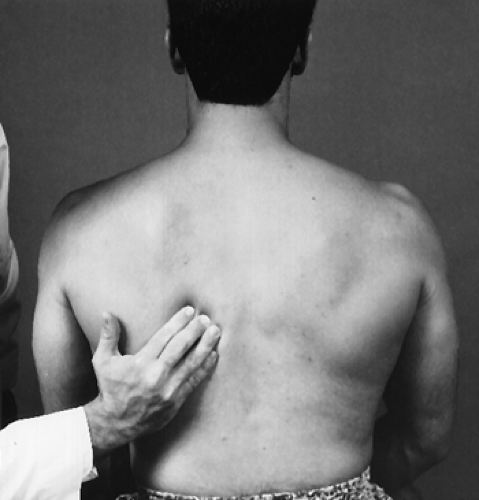

Begin at the origin at the base of the occiput, palpating superior fibers inferior toward the spine of the scapula (Fig. 5-27). Then, from the spine of the scapula, palpate the middle (Fig. 5-28) and inferior (Fig. 5-29) fibers down toward the T12 spinous process. Note any tenderness, spasm, palpable bands, or asymmetry of the muscles. Tenderness and spasm may be present secondary to hyperextension or hyperflexion injuries. Tight palpable bands may be secondary to active myofascial trigger points. According to Travell, myofascial trigger points in muscle are activated directly by trauma, overuse, overload, or chilling. They are activated indirectly by visceral disease, arthritis, and emotional distress.

Shoulder Range of Motion

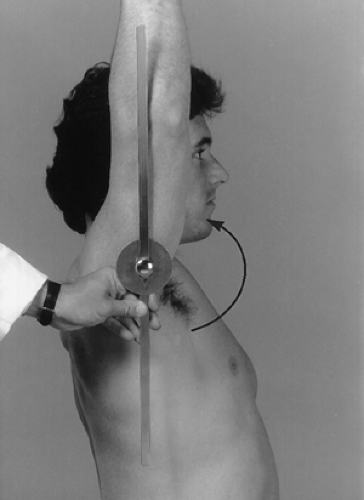

With the patient seated, place the goniometer in the sagittal plane at the level of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 5-30). Instruct the patient to elevate the arm forward while following it with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 5-31).

Normal Range

Normal range is 167° ± 5.7° from the 0 or neutral position.

Note: This expressed degree of motion probably did not permit enough external rotation and abduction to achieve 180° of flexion described by others.

| Muscles | Nerve Supply |

|---|---|

| 1. Anterior deltoid | Axillary |

| 2. Pectoralis major | Lateral pectoral |

| 3. Coracobrachialis | Musculocutaneous |

| 4. Biceps | Musculocutaneous |

With the patient seated, place the goniometer in the sagittal plane at the level of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 5-32). Instruct the patient to elevate the arm backward while following it with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 5-33).

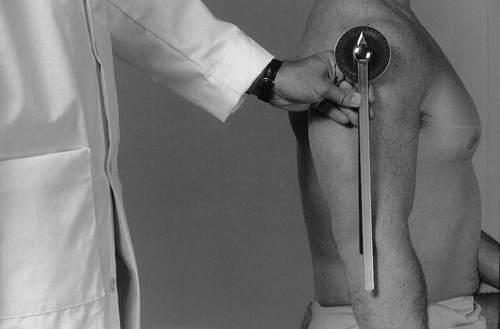

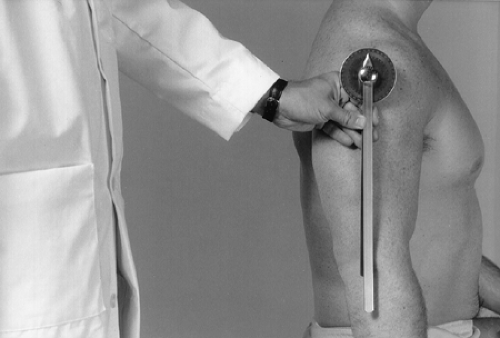

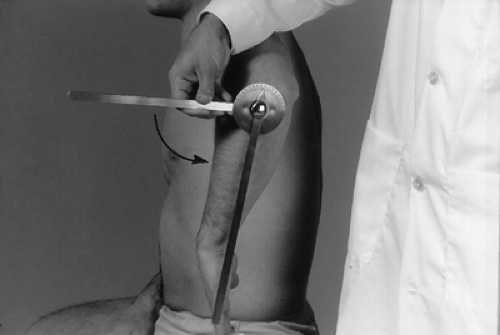

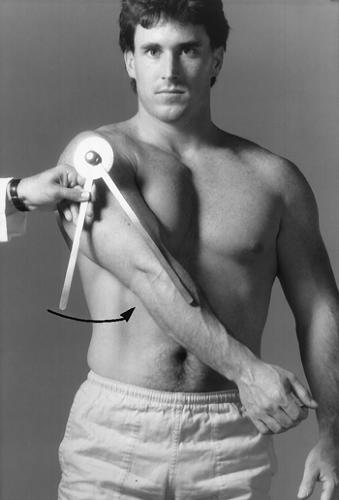

Have the seated patient abduct the arm to 90° and flex the elbow to 90°. This is the 0 or neutral position for rotation of the shoulder. Place the goniometer in the sagittal plane with the center at the lateral aspect of the elbow (Fig. 5-34). Instruct the patient to rotate the shoulder inward by moving the forearm so that the palm of the hand faces posteriorly, and follow the forearm with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 5-35).

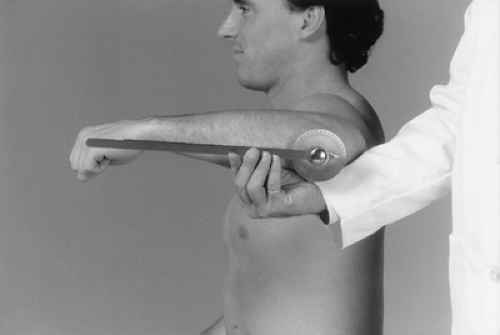

Have the seated patient abduct the arm to 90° and flex the elbow to 90°. This is the 0 or neutral position for rotation of the shoulder. Place the goniometer in the sagittal plane with the center at the lateral aspect of the elbow (Fig. 5-36). Instruct the patient to rotate the shoulder outward by moving the forearm so that the palm of the hand faces anteriorly, and follow the forearm with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 5-37).

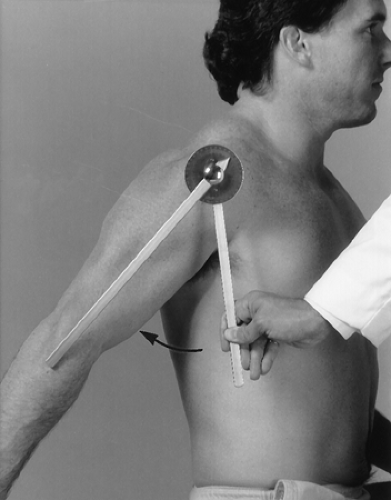

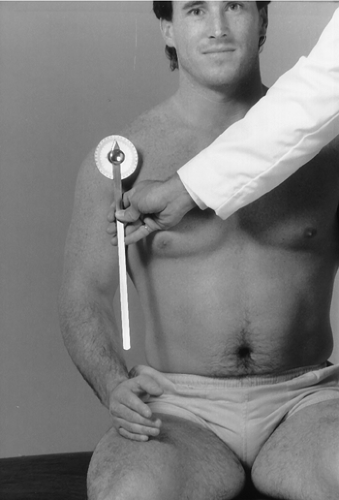

With the patient seated, place the goniometer in the coronal plane with the center at the level of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 5-38). Instruct the patient to raise the arm laterally. Follow it with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 5-39).

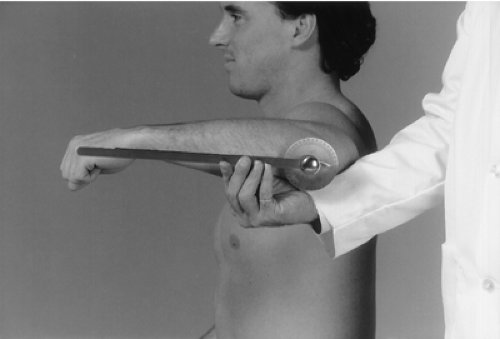

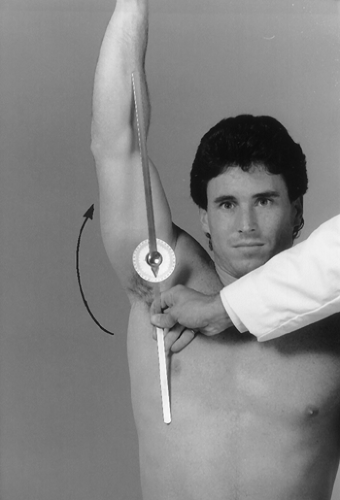

With the patient seated, place the goniometer in the coronal plane with the center at the level of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 5-40). Instruct the patient to raise the arm medially. Follow it with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 5-41).

Normal Range

Normal range is 75° or greater from the 0 or neutral position.

Note

Adduction is a composite movement of flexion and adduction. Most sources do not measure composite movements. I consider it a clinically important movement and think it should be measured.

| Muscles | Nerve Supply |

|---|---|

| 1. Pectoralis major | Lateral pectoral |

| 2. Latissimus dorsi | Thoracodorsal |

| 3. Teres major | Subscapular |

| 4. Subscapularis | Subscapular |

Impingement Syndrome (Supraspinatus)

Clinical Description

Impingement syndrome is a diagnostic entity that is a compression of the supraspinatus tendon and subdeltoid bursa in the subacromial space. The space can be compromised by various factors such as arthritic changes to the acromion or instability of the shoulder. This may cause chronic compression to the shoulder, which may cause inflammation with resultant tears. Supraspinatus inflammation is a common inflammatory condition of the shoulder that causes anterior shoulder pain. This inflammatory condition may be caused by trauma, overuse (especially overhead movements), or faulty body mechanics during athletic activity, such as pitching or bowling.

Especially in abduction, the patient has painful passive range of motion and limited active range of motion and is apprehensive while performing these movements. The painful arc is usually between 60° and 90° of abduction. During this range the greater tuberosity passes under the acromion and the coracoacromial ligament. Pain and anterior spasm of the shoulder may indicate a moderately inflamed swollen tendon. If the irritation of the tendon continues, calcific deposits may develop and lead to calcific tendinitis.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Anterolateral shoulder pain

Pain sleeping on the affected side

Stiffness

Catching of the shoulder during use

Pain on active and passive range of motion

Local tenderness

|

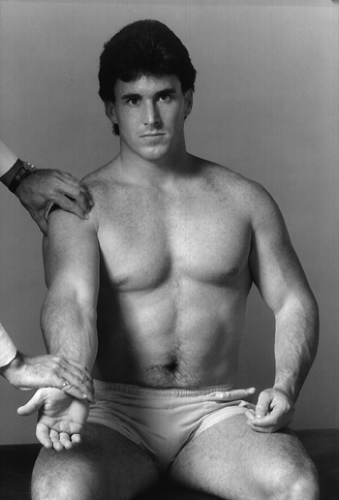

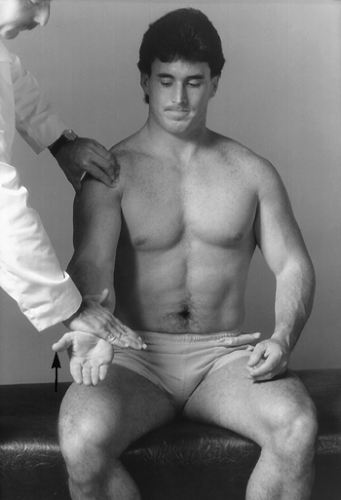

Procedure

With the patient seated, instruct him to abduct the arm to 90° with the arm between abduction and forward flexion. Instruct the patient to abduct the arm against resistance (Fig. 5-42).

Rationale

Resisting shoulder abduction stresses mainly the deltoid muscle and the supraspinatus muscle and tendon. Pain and/or weakness over the insertion of the supraspinatus tendon may indicate degenerative tendinitis or a tear of the supraspinatus tendon. Pain over the deltoid muscle may indicate a strained deltoid muscle.

Apley Scratch Test (3)

|

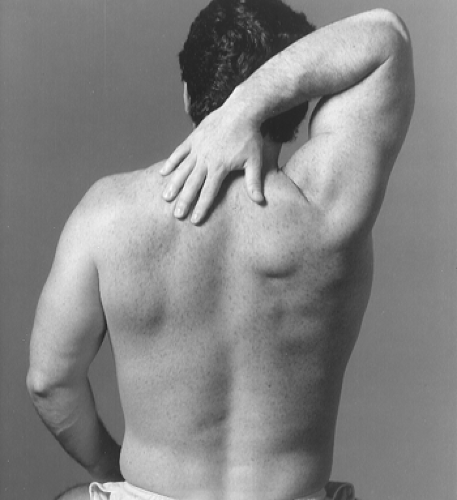

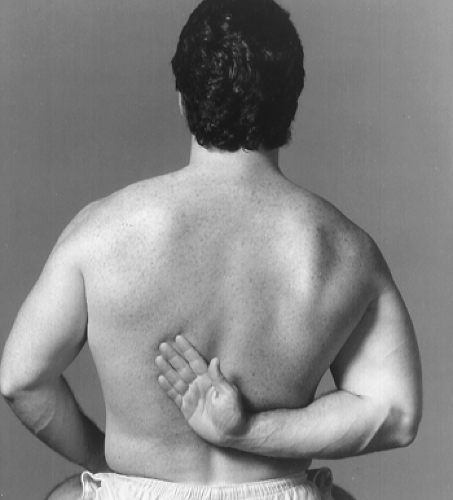

Procedure

Instruct the seated patient to place the hand on the side of the affected shoulder behind the head and touch the opposite superior angle of the scapula (Fig. 5-43). Then instruct the patient to place the hand behind the back and attempt to touch the opposite inferior angle of the scapula (Fig. 5-44).

Rationale

Actively attempting to touch the opposite superior and inferior aspect of the scapula places stress on the tendons of the rotator cuff. Exacerbation of the patient’s pain indicates degenerative tendinitis of one of the tendons of the rotator cuff, usually the supraspinatus tendon.

Hawkins-Kennedy Impingement Test (4)

|

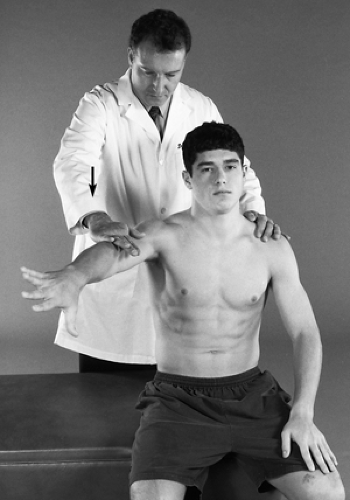

Procedure

With the patient standing, flex the shoulder forward to 90°, then force the shoulder in an internal rotation without resistance by the patient (Fig. 5-45).

Neer Impingement Sign (5)

|

Procedure

With the patient seated, grasp the patient’s wrist and passively move the shoulder through forward flexion (Fig. 5-46).

Rationale

Moving the shoulder through forward flexion jams the greater tuberosity of the humerus against the anterior inferior border of the acromion. Shoulder pain and a look of apprehension on the patient’s face indicate a positive sign. This indicates an overuse injury to the supraspinatus muscle or sometimes to the biceps tendon.

Tendinitis (Bicipital)

Clinical Description

The biceps brachii has two heads, the long and the short. The long head originates from the superior lip of the glenoid fossa, proceeds laterally, and angles 90° at the bicipital groove on the superior aspect of the humeral head. It is the affected tendon in bicipital tendinitis (Fig. 5-47). Bicipital tendinitis is a chronic condition of shoulder pain with tenderness over the bicipital groove (see Fig. 5-51). Most cases are associated with lesions such as synovitis of the surrounding capsule, adhesive capsulitis, osteophytes in the area of the bicipital groove, or rotator cuff tears. True isolated bicipital tendinitis allows a full free range of passive movement.

|