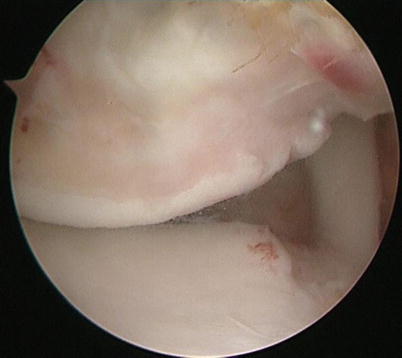

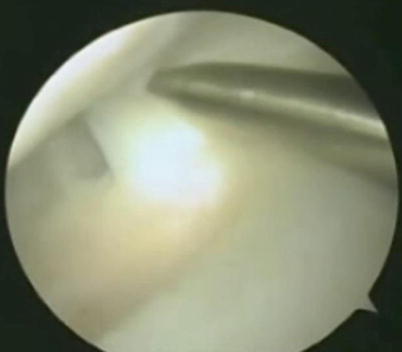

Fig. 18.1

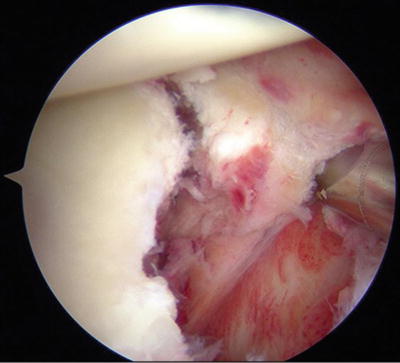

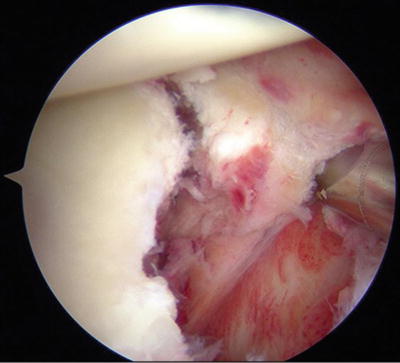

Bankart lesion

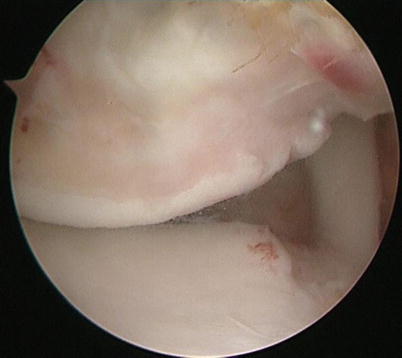

This injury can also come with a bony fragment from the anteroinferior edge of the glenoid [61]. The detached labrum fails its deepening effect, therefore destabilizing the glenohumeral joint. This mechanism is increased when a bony lesion is also present (bony Bankart) (Fig. 18.2), since it contributes to decrease the glenoid surface. During a trauma in which the humeral head, while in abduction and external rotation, is forced anteriorly, a compression fracture can occur as the superior posterolateral aspect of the head hits the anterior glenoid rim (Fig. 18.3). This occurrence was identified by Hill and Sachs in 1940 [20], and it is present in 40–90 % of all anterior shoulder dislocation [61, 72]. When the defect on the superior posterolateral aspect of the humeral head engages the anterior glenoid rim, the lesion becomes an engaging Hill-Sachs (Fig. 18.4). Typically it happens with 90° of abduction and a various degree of external rotation [10, 47].

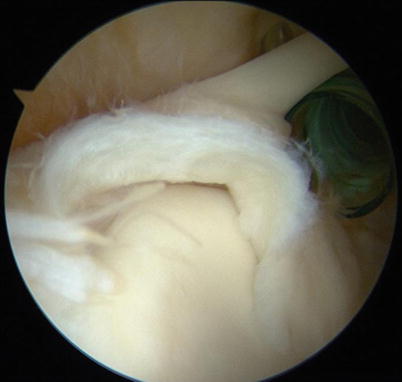

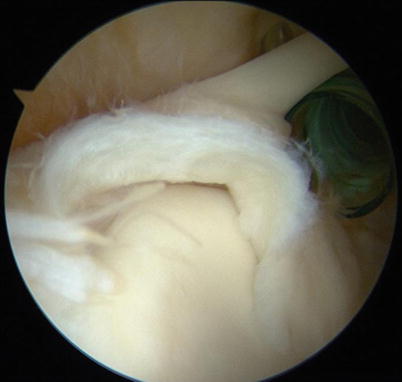

Fig. 18.2

Bony Bankart lesion

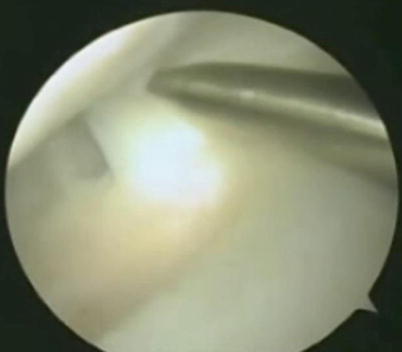

Fig. 18.3

Hill-Sachs lesion

Fig. 18.4

Engaging Hill-Sachs lesion

Although less common, other structures can be injured following an anterior shoulder dislocation. Specially in overhead/throwing athletes, the superior labrum can detach at the biceps tendon/labrum complex as described by Andrews et al. in 1985 [1], and successively, Snyder named this injury Superior Anterior to Posterior Lesion (SLAP) (Fig. 18.5) and classified it into four types [58].

Fig. 18.5

Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior Lesion (SLAP)

Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) (Fig. 18.6) is another well-described cause of post-traumatic anterior shoulder instability, accounting up to 9 % of the cases [64, 70]. It has been also described as an association between anterior shoulder instability and a tear of the rotator interval complex, as described by Rowe and Zarins [52].

Fig. 18.6

Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL)

18.5 Clinical and Diagnostic Examination

Examination starts with a careful history. Even in the acute setting, a detailed history on the trauma pattern can help in diagnosing the underlying injury. Moreover, a complete neurovascular assessment is mandatory in the acute dislocation, since an axillary nerve injury occurs in 5–35 % of first injury [49], and a gross physical examination should also evaluate the presence of obvious deformity, open wounds, and limited range of motion. In the subacute setting, the examiner should focus on age at the first dislocation, mechanism of injury, type and level of played sport, any further dislocation and shoulder positions that lead to dislocation, and the total number of episodes. Muscle status should be assessed, together with the presence of deformities and sensory-motor impairment. Examination should also encompass generalized ligamentous laxity test. The main essential differential diagnosis should focus on traumatic versus atraumatic shoulder instability. The first one follows a traumatic injury, usually is unidirectional, and frequently needs surgery to be fixed (TUBS), and the second one is the result of a generalized ligament laxity, shows a multidirectional instability, and is mainly addressed by physical therapy (AMBRI) [63].

The apprehension test is considered positive when elicits apprehension while the patient is supine and the arm is passively abducted and externally rotated both to 90°. Sometimes patients experience pain, although the pain alone has a lesser predictive value [52]. If the patient complains for discomfort and apprehension while the shoulder is at 90° of abduction and external rotation, the examiner can push posteriorly the humeral head. If this maneuver lowers the apprehension, the so-called relocation test is considered positive, as described by Jobe et al. [29]. When the examiner removes suddenly his hand after the relocation test, the patient could experience the symptoms. This is defined as a positive surprise test [57]. A study evaluating the three tests [37] showed that the surprise test was the single most accurate test (sensitivity = 63.89 %; specificity = 98.91 %) followed by the apprehension test (sensitivity = 52.78 %; specificity = 98.91 %), the relocation adds few value to the examination, being the less accurate (sensitivity = 45.83 %; specificity = 54.35 %).

The anterior and posterior drawer tests [16] and the load and shift tests [41] are used to assess the stability of the glenohumeral joint. The drawer tests are considered positive if the humeral head has an increased translation compared to the contralateral shoulder. The load and shift test is considered positive when the humeral head could be shifted anteriorly off the glenoid.

Radiological evaluation should include routine X-rays in three views, a true antero-posterior view, the West Point Axillary view, and the Apical Oblique view. This set of view allows to evaluate the anteroinferior glenoid rim. When a bone loss is suspected, routine X-rays should be supplied with CT-scan that allows for a quantification of the glenoid bone loss. To this purpose, different methods have been described [24, 54, 60]. MRI should be considered to evaluate soft tissue injuries, including labrum, rotator cuff, and glenohumeral ligaments, and for these latter, a better view could be achieved by using the ABER position [55]. The intra-articular injection of gadolinium could be used to enhance the diagnostic power (arthro-MRI) once the post-traumatic hemarthrosis in the acute setting has been solved. Arthro-MRI identifies labral tears with a sensitivity of 88–96 % and a specificity of 91–98 % [69].

18.6 Treatment Strategy

The treatment of anterior shoulder instability is a heavily debated issue. A lot of factors enter in the decision-making process: age and level of activity of the patient, the kind of sport and the role of the athlete (overhead/thrower vs nonoverhead/nonthrower), the type of lesion (soft tissue or soft tissue and bony lesion), the number of dislocations, and the timing with respect to sport season.

The athlete incurring in a shoulder dislocation in the mid-season, who wish to finish the season, has no alternatives than nonoperative management. But no all the athletes are amenable to be treated nonsurgically. Although evidences are little, the following criteria have been proposed: (1) little or no pain, (2) patient subjectivity, (3) near normal range of motion, (4) near normal strength, (5) normal functional ability, and (6) normal sports-specific skills. When the strength is 80–90 % of normal and mild apprehension, the athlete could return to play with an abduction and external rotation limiting brace that can be removed once the symptoms are gone [40].

18.6.1 Nonoperative Management

Immobilization, physical therapy, and bracing, with a delayed return to activity, are the basis of nonoperative management. The duration and position of the immobilization are controversial. Itoi et al. used the MRI to assess if there were differences in immobilizing the arm internally or externally rotated in patients affected by a Bankart lesion. They found that immobilization in internal rotation displaces the labrum and immobilization in external rotation better approximates the Bankart lesion [26]. In a later prospective study, comparing patients randomly assigned to immobilization in either internal or external rotation, Itoi and colleagues found a significantly lower recurrence rate in the external rotation group than in the internal rotation group (26 % vs 42 %), with a relative risk reduction of 38.2 %. In the subgroup of patients who were 30 years of age or younger, the relative risk reduction was even more substantial (46.1 %) [25]. However, in a more recent prospective randomized study on 188 patients with a primary anterior traumatic dislocation of the shoulder randomly assigned to immobilization in either internal rotation or external rotation for 3 weeks [35], the authors showed that the recurrence rate was 24.7 % in the internal rotation group and 30.8 % in the external rotation group (p = 0.36).

18.6.2 Operative Management

Although on the basis of weak evidences, there is general agreement among surgeons that failure of nonoperative management, recurrent dislocation, large or engaging Hill-Sachs lesions, and glenoid bone loss greater than 20 % are factors pushing towards surgery [67]. Outcomes from both nonoperative [39, 51] and operative [53] treatments showed that age is a primary risk factor for recurrence. In the acute setting, indications to surgery are the presence of a proximal humerus fracture requiring surgery, irreducible dislocation or interposed tissue or nonconcentric reduction, and instability during sports-specific drills [46].

Studies comparing nonoperative to operative treatment of initial traumatic anterior dislocation showed that the recurrence rate is higher for the nonoperative option [7, 28, 34].

Early surgical stabilization compared to nonoperative treatment leads to better outcomes and smaller recurrence rate, especially for younger and more active subjects. Both at short-term follow-up (7 % vs 46 %) and at longer-term follow-up (10 % vs 58 %) operative management is associated with a significantly lower rate of recurrent instability for primary anterior shoulder dislocation [8].

Nearly 90 % of shoulder stabilization surgeries are arthroscopically performed, while a significant decline in the incidence of open Bankart repair has been observed in the USA [74]. In 2010, a meta-analysis on 6 studies, for a total number of patients of 501, 234 suture anchors and 267 open, concluded that arthroscopic repair using suture anchors results in similar recurrence and reoperation rate compared to open Bankart repair [50]. A recent systematic review of level I to IV studies showed that arthroscopic suture anchor and open Bankart techniques for anterior shoulder instability yield comparable results in terms of recurrence rate (arthroscopic suture anchor 8.5 %, open Bankart repair 8 %), clinical outcome scores, return to play (arthroscopic suture anchor 87 %, open Bankart repair 89 %), and incidence of postoperative osteoarthritis [19].

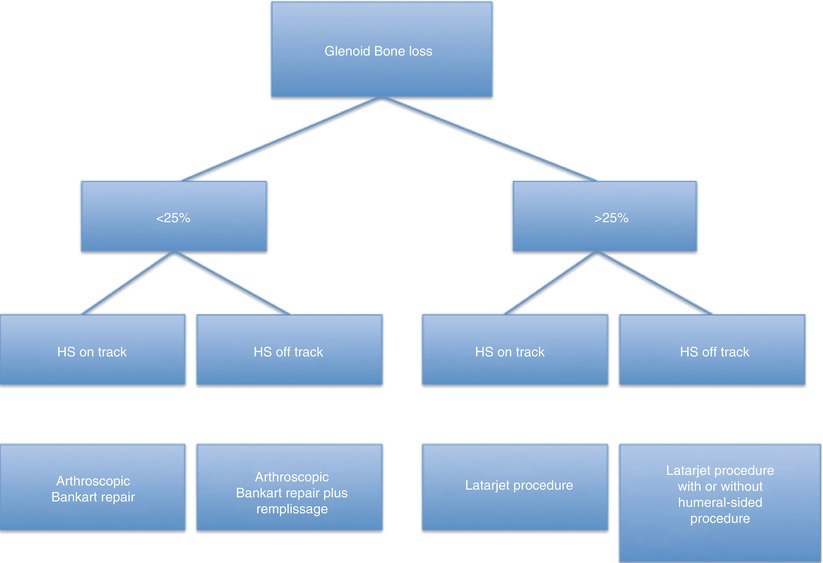

A recently published systematic review has shown that there is no significant difference in recurrence rate of instability among open Bankart procedures (5.5 %), Bristow-Latarjet procedures (14.3 %), and arthroscopic Bankart procedures (14.7 %). The open Bankart repair yielded to the lowest recurrence rate, clustering the shoulders by the amount of bone loss or the presence of an engaging Hill-Sachs, showed that for glenoid bone loss lesser than 30 % or non-engaging/non-severe Hill-Sachs lesions, open Bankart repair was successful in 100 % of patients without recurrences. Conversely for greater than 30 % glenoid bone loss or engaging or severe Hill-Sachs, open Bakart repair yielded 57.1 % of recurrences, while for the same conditions, the Bristow-Latarjet achieved a 14.3 % rate of recurrent instability [15]. Balg and Boileau assessed that bone loss (both at the glenoid or at the humeral side), patient age under 20 years at the time of surgery, contact sports or overhead activity, and shoulder hyperlaxity are clear risk factors for recurrence after arthroscopic Bankart repair [3, 6]. Therefore, they successively developed the “instability severity index score,” a scoring system that takes into account the previously named risk factors and determines which patient would be better treated by an open procedure [3]. Failed shoulder stabilization procedures in an athlete are always a tough issue for the orthopedic surgeon. Causes of failure can be relative to a new trauma or an underestimated lesion at the time of the primary treatment. Several studies support the arthroscopic Bankart repair as a feasible option even in the revision setting [2, 5, 12, 33, 42, 43, 48]. But revision Bankart repair generally yields to lower results compared to primary repair in terms of recurrence rate, return to play, and clinical outcomes [17]. With regard to bony defects, there is general agreement that glenoid bone loss greater than 25 % should be addressed by bony procedures to widen the glenohumeral articular surface [38]. But less agreement there is about bipolar bone loss lesions when the glenoid lesion is lesser than 25 % also because of the lack of a shared quantification method for humeral-sided bone loss. Itoi and colleagues in 2007 introduced a new concept, the glenoid track [71]. When the arm is abducted, the contact zone between humeral head and glenoid shifts from the inferomedial to the superolateral portion of the posterior aspect of the humeral head; that area is named glenoid track. This concept is consistent to the one by Burkhart and De Beer [10] about engaging versus non-engaging Hill-Sachs lesions. Combining these concepts, Di Giacomo, Itoi, and Burkhart recently proposed to divide the lesions into “on track” and “off track” [13]. In the presence of a Hill-Sachs, if the medial margin of the lesion falls inside the glenoid track, it will be on track and therefore will not engage. On the contrary, if the medial edge of the lesion falls medially to the margin of the glenoid track, the Hill-Sachs will be off track and an engaging lesion. The authors proposed that for off-track lesions, regardless of the amount of the glenoid defect, a procedure addressing the humeral head should be considered [13] (Fig. 18.7). An increasing number of studies support the concept of the glenoid track as a powerful method in the diagnostic and treatment approach [65].

18.7 Rehabilitation and Return to Play

Rehabilitation after surgical treatment is tailored for each athlete according to the type of surgery he underwent and the role he plays. However, the early phases are shared despite the nonoperative or surgical treatment and the sporting activity. A sling during the first 2 weeks allows for soft tissue protection, reduction of inflammation, and healing. Limited passive and gentle ranges of motion (ROM) are useful during that period to avoid the risk of shoulder stiffness. Usually from the third/fourth week, ROM are gradually increased, and isotonic, closed-chain exercises for rotator cuff muscles and other periscapular stabilizers are started, in order to favor joint stability. After four postoperative weeks, the sling is discontinued, and the patient can sleep with a pillow to keep the arm at 45° of abduction. Successively, the goals of the rehabilitation are to recover full ROM and increase the muscular strength and the joint neuromuscular control. The final phase is targeted to recover specific sports drills. Progression to advanced phases of the rehabilitation is based on pain, ROM gain, strength of the stabilizing periscapular muscles, and joint control. On average, a 4-month period is necessary for return to sport [27]. Usually athletes are allowed to return to sport if they show a comparable motion, strength, and stability to the contralateral side during specific sports drills [11, 68].

References

1.

2.

Arce G, Arcuri F, Ferro D, Pereira E (2012) Is selective arthroscopic revision beneficial for treating recurrent anterior shoulder instability? Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(4):965–971. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-2001-0 PubMedCentralCrossRefPubMed

3.

Balg F, Boileau P (2007) The instability severity index score. A simple pre-operative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 89(11):1470–1477. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.18962 CrossRefPubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree