Chapter 24 Shoes and shoe modifications

With few exceptions, the efficient function of virtually all lower extremity orthotic devices depends heavily on appropriate footwear.15 The efficacy of an assistive device can be greatly enhanced through good footwear selection and/or shoe modifications. If a patient is unable to find a shoe to accommodate his or her ankle–foot orthosis (AFO), the brace is rendered useless. To complicate matters, many people are accustomed to purchasing and wearing ill-fitting shoes. Of note is a study by the AOFAS Women’s Footwear Committee of 356 women, which found that nearly 90% wore improperly fitting shoes.4 This chapter explores shoe anatomy and construction techniques; discusses shoe selection and the importance of proper shoe fit; and explains some of the most common shoe modifications and their corresponding indications for use.

Anatomy of a shoe

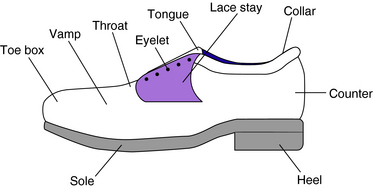

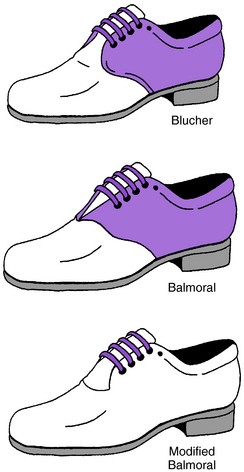

The most important parts of the shoe are illustrated in Figure 24-1. The terms used to describe parts of the upper include (1) toe box—part of the shoe that covers the toes; (2) vamp—part of the upper that covers the instep; (3) counter—section of the shoe anterior to the heel; (4) tongue—piece that covers the dorsum of the foot; and (5) throat—section where the tongue meets the vamp. The two basic types of throat openings are the blucher and the balmoral; one common variation is the modified balmoral (Fig. 24-2).

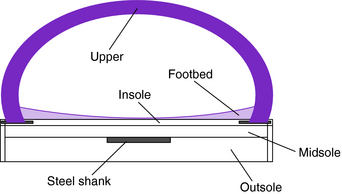

Figure 24-3 depicts a cross-section of the shoe. It illustrates the different layers of the sole: (1) insole—layer of sole closest to the foot; (2) midsole—layer directly below the insole that adds extra support, stability, and comfort to the shoe (not all shoes have a midsole); (3) outsole—bottommost part of the sole that comes into contact with the ground; (4) foot bed, some shoes have an additional removable foot bed inside the shoe, on top of the insole, for added comfort; and (5) shank—bridge between the heel and the ball area of the shoe; the shank portion of the shoe may be reinforced with a steel shank, a strip of spring steel between the outsole and insole.

Shoe construction

The two main components of interest in shoe construction are (1) the technique used to attach the sole to the upper, which can be accomplished in a number of ways depending on the type of shoe and its intended use; and (2) the shoe materials used in the construction of both the upper and the sole.12

Sole attachment techniques

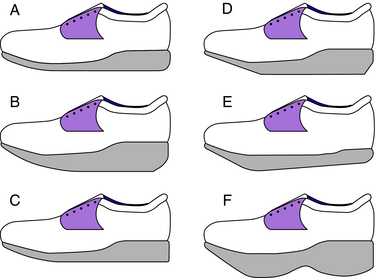

The manner in which a sole is attached to the upper defines some of its functional properties and its appearance and can affect the fit of the shoe. Six major types of sole attachment techniques are considered (Fig. 24-4).

The Goodyear welt takes its name from the Goodyear sole-stitching machine that was invented in the late 1880s.17 This technique is distinguished by its prominent use of a welt. A welt is a narrow strip of flat leather that is chain stitched to both the upper and the insole. The outsole then is lock stitched to the welt. Use of this technique yields a strong and structurally sturdy shoe. In order to provide a flat tread surface, the space between the insole and outsole is filled with ground cork or some other lightweight material. Shoes constructed with a Goodyear welt tend be less flexible and not as lightweight as other types. The Goodyear welted shoe lends itself to the attachment of a metal bracing system better than any other type of shoe.

The Littleway and McKay are two different attachment techniques wherein the upper is fastened to the sole via staples and the outsole then is attached with either lock stitches (Littleway) or chain stitches (McKay).17 This construction leads to the formation of a very flexible shoe, such as a moccasin or deck shoe.

Shoe construction materials

Dozens of base materials and literally hundreds of variations of those base materials are used in the manufacture of shoes. In this section, discussion is limited to general categories of materials found in shoes used in conjunction with orthoses and with or as assistive devices.

Shoe shape

The most important adage in shoe fitting is “Fit the shoe to the foot, not the foot to the shoe.”3,8,10,13,18 Both the shape of the sole and the shape of the upper must be considered. Some shoes have pointed toe boxes; others have rounded, or oblique, toe boxes. Some shoes are wide in the shank area whereas others are very narrow. Shoes that are considered to be in-depth shoes have extra room throughout the shoe, an extra deep toe box, and one or more removable foot beds. There are nearly as many variations of shoe shapes as there are foot shapes.

Lasts

The shape of a shoe is determined entirely by the last upon which it is made. Each differently shaped last produces a differently shaped shoe. The last is a solid, three-dimensional plastic or wooden model. If a shoe is made to be available in multiple true widths, then the manufacturer must use a different last for each size and width combination. The exorbitant cost of manufacturing the large number of lasts necessary to make shoes in multiple widths is a primary deterrent to many popular shoe companies producing shoes that are available in different widths. A last is measured at as many as 10 points, including the heel-to-toe measurement, heel-to-ball measurement, and circumferential measurements at the ball, waist, instep, and heel.17 Each time one of these measurements increases, the other measurements increase proportionally to create larger lasts. Different style shoes made on different lasts, even shoes made by the same company, fit differently.17

Sizes and widths

As variable as last shape is from manufacturer to manufacturer, shoe sizing is just as confusing. There is little or no regulation of sizing in the footwear industry.5,17 The most widely used scale in U.S. shoe manufacturing is the “common” scale, but what value the manufacturers choose as their baseline size is up to the individual manufacturer. To compound matters, the system itself makes little sense and could be considered archaic.

The shoe sizing system currently used by the majority of U.S. shoe manufacturers today is an evolution of a system developed in England in the mid-1300s AD by King Edward II. King Edward declared that three barleycorns, plucked from the center of the ear and laid end to end, would equal 1 inch. He decreed that 39 barleycorns would be equal to the size of the largest man’s foot, or 13 inches, thereby a size 13. Going backward from size 13, each size would equal one barleycorn, or approximately ⅓ inch. A child’s size 0 was equal to the width of a man’s knuckles, or 13 barleycorns (Edward decided that when an infant’s foot was equal to the width of a man’s knuckles, the time was appropriate for the infant to begin wearing shoes). After going up 13 sizes (or barleycorns) the sizes start over. Therefore, a baby’s foot (13 barleycorns) plus all 13 sizes of children’s shoes (13 more barleycorns) plus 13 sizes of men’s shoes (another 13 barleycorns) equals the length of 39 barleycorns, or a men’s size 13.7,17

Until the Civil War, mass-produced shoes were not available in “lefts” and “rights”; they were straight lasted shoes that could be worn on either foot.7 Twenty years later, Edwin Simpson of New York introduced a variation on the scale that, for the first time, included widths and half-sizes.19

Many other sizing system are in use around the world. In most of Europe (except for the United Kingdom), shoes are sized according to the Continental, or Euro, scale. The Euro scale evolved from a French scale called Paris points. One Paris point equals ⅔ cm. The system begins at 0 cm and increases. There are no half sizes. The Euro scale is a unisex metric system whereby each shoe size is ⅔ cm, less than an American full size but more than an American half-size. To review, a US men’s size 9 equals a US women’s size 10½ equals a Euro size 43.17

Shoe selection

Off-the-shelf shoes

It is generally accepted that there are seven basic types of shoes; the rest are considered variations of these basic styles.17 The seven basic shoe types are as follows: (1) boot—any footwear that extends proximal to the ankle; (2) clog—thick, wooden-soled, backless, slip-on shoe; (3) oxford—low-cut shoe fastened with laces; (4) moccasin—oldest form of shoe, low-vamp loafer, originally made entirely of one piece of leather; (5) mule—backless shoe or slipper with low or no heel; (6) sandal—shoe with an upper consisting of an arrangement of straps; and (7) pump—thin-soled, slip-on shoe with varying heel heights.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

to ¼ inch.

to ¼ inch.