Chapter 38 Orthoses for cerebral palsy

Pathophysiology

Regardless of the type of CP, it is the central control system that is damaged. The neurological lesion may produce different tone abnormalities. In a patient with pure spasticity, only the pyramidal system is damaged. In a patient with athetoid CP, only the extrapyramidal system is involved. Both systems are injured when a mixed pattern is seen. The central nervous system lesion affects the musculoskeletal system. Primary abnormalities include the following8:

These primary abnormalities cause secondary growth disorders of the musculoskeletal system as the neurological impairments occur early during growth and development. Normal bone growth occurs only if the bones are subjected to typical development stresses. Children who are unable to walk, run, and play at typical ages with typical movement patterns are likely to develop bone and joint deformities. Infantile bony alignment is markedly different than typical adult alignment. Normal developmental remodeling of fetal femoral anteversion and internal tibial torsion is unlikely in the absence of typical growth stresses. Development of normal foot alignment and function is in jeopardy if muscle function is abnormal or if the stresses on the foot are excessive due to spasticity or abnormal weight-bearing positions. Longitudinal bone growth occurs at the physes present at both ends of long bones. Much of that growth probably occurs while the child is resting. Muscle growth, on the other hand, is driven by stretch. Normally that stretch occurs when a child, whose bones have grown during sleep, gets up and starts to run and play. Ziv et al.31 showed that in order for normal muscle growth to occur, 2 to 4 hours of stretch per day is necessary. In addition, they showed that the muscles of spastic mice do not grow in response to stretch at the typical rate. The combination of this lack of response and the lack of “normal play” leads to secondary musculotendinous contractures.

Gait dysfunction in individuals with CP occurs as a result of these primary and secondary abnormalities, which rarely occur in isolation. Rather, they are multiple and consist of primary effects (due to the damage to the central nervous system), secondary deformities (from abnormal bone/muscle growth), and tertiary compensations (individual coping responses to minimize the gait inefficiency resulting from the primary and secondary abnormalities). Tertiary abnormalities are coping responses to restore lost attributes of normal gait19 and include the following:

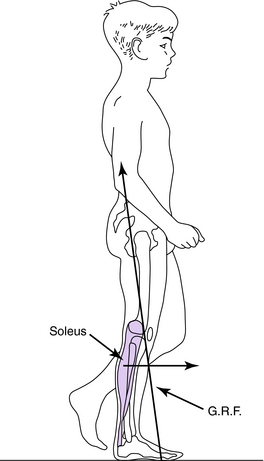

It is primarily the two-joint muscles (e.g., psoas, rectus femoris, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius) that are affected by excessive tone caused by CP. With time and growth, these muscles become contracted. It is interesting that the one-joint muscles (e.g., gluteus maximus, vasti, and soleus) typically are too long due to the chronic effects of walking in crouch. The crouch position of excessive hip and knee flexion in conjunction with either excessive ankle dorsiflexion or midfoot breakdown puts these muscles in a position of excessive elongation as they cross the joints. These are also the muscles that are primarily responsible for our ability to maintain upright posture.29 Upright posture requires good antigravity function of the one-joint muscles responsible for supporting body weight. Weakness and excessive elongation of these muscles in conjunction with spasticity of the two-joint muscles is primarily responsible for crouch gait. The management of ambulatory dysfunction in CP in the vast majority of cases is geared toward the treatment of crouch. The long-term consequences of crouch are excessive joint stress and gait inefficiency. This combination leads to decreasing ambulatory function in adolescence and adulthood due to joint pain and excessive energy costs.13,27 The frequency of these problems in adulthood is disturbingly high16 and ultimately is the reason why treatment of these problems in children and adults is so important.

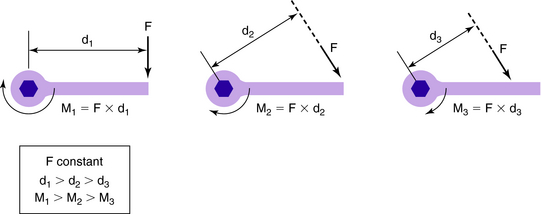

To understand and treat physical function deficits requires a basic understanding of mechanics. A lever arm or moment arm is defined as the distance from a point to a force that is perpendicular to the line of action of that force. The force (measured in Newtons) times the length of the lever arm (in meters) is equal to the moment that acts around the center of rotation (in Newton-meters). In general, the length of the bone serves as the lever, and the joint at the end of that bone serves as the center of rotation or fulcrum. The magnitude and direction of the moment depends upon the point of action of the applied force (Fig. 38-1).

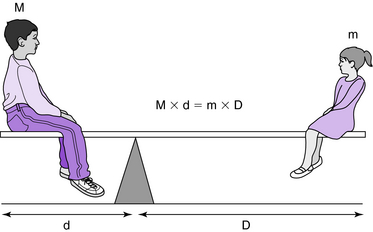

Moments are perhaps understood most easily if one thinks of a see-saw in which the mass of the larger individual times his or her distance from the fulcrum is equal to that of the smaller individual times her or his distance from the fulcrum (Fig. 38-2).

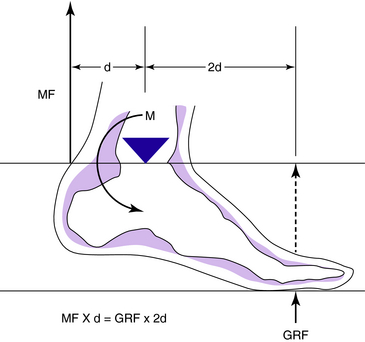

The principle is the same in walking. External moments produced by the ground reaction and inertial forces plus weights of the lower extremity segments are resisted by internal moments produced by the action of muscles, tendons, and/or ligaments (Fig. 38-3).

Lever-arm dysfunction is a term originally coined to describe the particular orthopedic deformities that arise in an ambulatory child with CP. However, the condition is common to any traumatic or neuromuscular problem that produces alteration of the bony skeleton. Lever-arm dysfunction, then, describes a general class of bone modeling, remodeling, and/or traumatic deformities that includes hip subluxation, torsional and angular deformities of long bones, and/or foot deformities. Because the muscles and/or ground reaction forces must act on skeletal levers to produce locomotion, abnormalities of these lever-arm systems greatly interfere with the child’s ability to walk.8,9

In a condition such as CP, the muscle and/or ground reaction forces are neither appropriate nor adequate because of muscle contractures, poor selective motor control, and/or abnormality of the bony lever arms. The five distinct types of lever arm deformity are (1) short lever arm, (2) flexible lever arm, (3) malrotated lever arm, (4) abnormal pivot or action point, and/or (5) positional lever-arm dysfunction (Table 38-1). A comprehensive discussion of lever-arm dysfunction is beyond the scope of this chapter, but a common example of lever-arm dysfunction that is seen in spastic diplegia will serve to illustrate the problem.

Table 38-1 Examples of lever arm dysfunction

| Type | Deformity |

|---|---|

| Short lever arm | Coxa valga |

| Flexible lever arm | Pes valgus |

| Malrotated lever arm | External tibial torsion |

| Abnormal pivot or action point | Hip subluxation/dislocation |

| Positional lever-arm dysfunction | Erect vs crouch gait |

In normal gait during the second half of the stance phase, stability of the knee is maintained without quadriceps action by a mechanism termed the plantarflexion/knee-extension couple (Box 38-1). That is, the action of the soleus at the ankle restrains forward motion of the tibia over the foot and in so doing maintains the ground reaction force in front of the knee. The result is that the ground reaction force acting on the lever arm of the forefoot produces an extension moment at the knee, which in turn maintains the joint in extension without the aid of the quadriceps (Fig. 38-4). However, the typical child with spastic diplegia frequently has femoral anteversion in conjunction with pes valgus and/or external tibial torsion. The plane of the foot often is as much as 40 degrees external to the plane of the knee. In addition, a valgus foot is an ineffective lever because it is supple rather than rigid. As a result, even if the magnitude of the ground reaction force were normal, because the lever arm is supple and maldirected, the magnitude of the extension moment can be greatly reduced (Fig. 38-5). Fortunately, lever-arm dysfunction usually is correctable with appropriate orthopedic surgery and/or bracing.

BOX 38-1 PlantarFlexion/Knee-Extension Couple

A moment in the musculoskeletal system is the product of the muscle force times the length of the lever arm on which the muscle force is applied. Joint moments are necessary to provide for stance phase stabilization and propulsion. Stance phase stabilization is necessary because joints are inherently unstable. Without ligament and muscle function, the joints would collapse under the force of gravity. To maintain an upright posture (antigravity position), the hip, knee, and ankle joints are stabilized primarily under the influence of the hip extensors, vasti, and gastrocsoleus. To initiate and maintain walking, propulsive muscle forces are necessary to propel the body and the lower extremity body segments. Winter29 showed that 50% of the moment production to maintain upright standing posture is supplied by the gastrocsoleus. The soleus typically is thought of as an ankle plantarflexor. However, when the foot is in a plantigrade position during second rocker, the soleus is active and works eccentrically to restrain the forward movement of the tibia. Therefore, it functions as a knee extensor. This is known as the plantarflexion/knee-extension couple. This normal coupling requires normal foot function, structure, and alignment, and normal gastrocsoleus activation and strength. Pathology can adversely affect any or all of these. Consequently, coupling frequently is excessive or insufficient. The knee may be driven into hyperextension during midstance by a well-aligned foot in the presence of gastrocsoleus spasticity or contracture. Unfortunately, the insufficient plantarflexion/knee-extension couple is common and contributes to crouch gait. Appropriate surgery and/or orthotic management can be effective in treating this deficiency. Likewise, inappropriate surgery and/or bracing not only are ineffective but also can cause iatrogenic worsening. These concepts are illustrated in specific examples in the section on orthotic management.

Evaluation of foot deformity is challenging (see Box 38-2). Two common foot deformity types exist in children with CP. In patients with hemiplegia, the equinovarus foot deformity is most common and may be associated with pes cavus. In individuals with diplegic and quadriplegic CP, the dominant foot deformity is equinovalgus. Although the etiology of this foot deformity is not completely certain, it most likely is related to equinus of the hindfoot (primarily gastrocnemius contracture and spasticity) leading to excessive forefoot weight-bearing early in a child’s development when the structure of the foot’s longitudinal arch is incompletely developed. Up until about age 6 years, pes planus is typical. With typical development, the arch forms and develops. In the case of neuromuscular pathology, this process may not occur, and equinovalgus foot deformity with midfoot instability can develop. With time, a forefoot varus deformity is not uncommon (Fig. 38-6). Treatment of this complex foot deformity type may require management of not only hindfoot equinus but also midfoot instability and forefoot varus.

BOX 38-2 Foot Physical Examination

The foot should be examined in non-weightbearing to determine segmental alignment of the forefoot to the hindfoot in the subtalar joint neutral position. The patient is prone with the foot over the end of the examining table. For examination of the right foot, the left thumb and index finger of the examiner are placed around the talonavicular joint medially and laterally (Fig. 38-6). The examiner’s right thumb and index finger grasp the necks of the 4th and 5th metatarsals. The forefoot is then pronated and supinated until the examiner feels that the navicular is “reduced” in line with the head of the talus. The head of the talus is equally covered medially and laterally by the navicular. The forefoot is then loaded with slight dorsiflexion pressure on the necks of the 4th and 5th metatarsals to mimic weightbearing. In the subtalar joint neutral position, the alignment of the hindfoot relative to the tibia and the forefoot relative to the hindfoot can be assessed to identify deformities that may influence foot position and foot motion in weightbearing. Identification of subtalar neutral position also provides insight into the presence or absence of atypical tibial torsion and aids in the crucial differentiation between tibial torsion and foot deformity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree