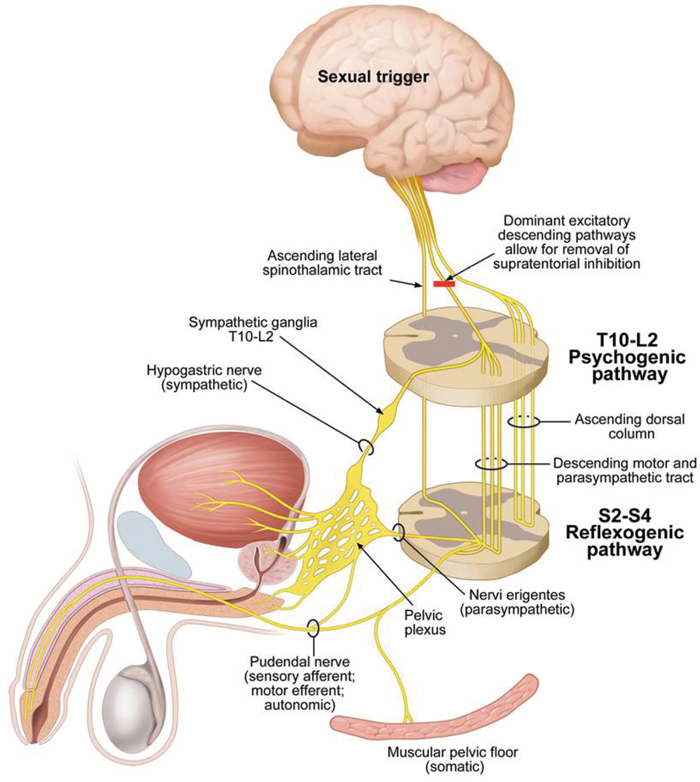

14 Key Points 1. Sexuality is a high priority for men and women with SCI. 2. Level and completeness of injury will determine the capacity for psychogenic/reflexogenic genital arousal and the ability to ejaculate. 3. Orgasm is possible in ∼ 40 to 50% of men and women after SCI. 4. Pregnancy and labor, but not fertility, are affected in women with SCI: fertility is affected in men due to erection and ejaculation difficulties as well as altered semen quality post-SCI. 5. Therapeutic effectiveness is maximized by using a comprehensive Sexual Rehabilitative Framework. Sex after spinal cord injury (SCI) matters—a lot. Those of us working in the field of SCI rehabilitation for years have understood the importance of sexual and fertility rehabilitation to men and women with SCI. Sexuality is even recognized as an activity of daily living by the American Occupational Therapy Association, thereby rendering it a rehabilitation priority. Its significance is exemplified in a recent survey by Anderson1 on what gain of function was most important to quality of life in 681 persons with SCI (of 681 participants, 25% were female, 65% were male, and 10% chose to participate anonymously): the majority of individuals with paraplegia felt regaining sexual function was their highest priority, and for individuals with quadriplegia, it was the second-highest priority (preceded only by regaining hand and arm function), placing sexual function above the return of sensation, walking, and bladder and bowel function. Furthermore, the vast majority of individuals with SCI felt their injury has altered their sexual sense of self and that improving their sexual function would improve their quality of life.2,3 Health care professionals are often either too intimidated to discuss the topic of sexuality with their patients with SCI, or they feel they do not have the skills or knowledge to handle the questions raised. Understanding how changes to sexuality occur following SCI and how they can be assessed and therapeutically managed in a comprehensive way will serve to promote long-term gains rather than short-term solutions. Utilization of a Sexual Rehabilitative Framework is a practical method for addressing the complexities of sexuality as it relates to the various psychological, physical, medical, and relationship changes that occur with SCI. Sexuality is much more than the performance of sexual acts. Sexual response is a feedback loop or circuit that is dependent on the emotional context, physical reactions, and influence of moment-to-moment, reinforcing triggers or negative distracters.4 The vast majority of men and women with SCI find it difficult to become physically aroused, and more women (74.7%) than men (48.7%) have difficulty becoming psychologically aroused.2,3 Furthermore, loss of sensory or motor ability or both forces an appreciation of the power of “brain or cerebral sex.” Focusing on cerebrally initiated sexual response can, despite lost abilities, result in an adapted but very satisfying sexual experience. Those areas that remain sensate take on a sexually arousing role (i.e., neck and ear stimulation has led to “eargasms” after quadriplegia), even if such body areas were not in the sexual repertoire prior to injury. In other words, the brain is always adapting its “software” despite the “hardware” being altered after SCI. This form of sexual neuroplasticity is a new science and Vancouver (BC, Canada) researchers have begun testing early “sexual sensory substitution” methods on subjects to try and regain sexual perception below the level of injury.5 Arousal is triggered by many inputs into the cerebral cortex: all the five senses to the brain, afferent sensory, and hormonal influences are assessed to generate a neuronal signal coordinated in the limbic system, hypothalamus, and other midbrain structures. Brain descending pathways are both excitatory and inhibitory: in a non-sexual situation, a strong inhibitory tone exists. When a peripheral or central sexual stimulation reaches a sufficient level, then increasing excitatory and reduced inhibitory signals activate the spinal centers to trigger genital arousal and ejaculation. In other words, the efferent outflow of signals from the brain down the spinal cord is impeded until our brain “allows” these messages to pass: when the healthy brain “feels safe,” the inhibition is removed and the spinal reflexes are released. In able-bodied individuals, sexual arousal involves coordinated participation of all three nervous systems: (1) sacral parasympathetic (pelvic nerve), (2) thoracolumbar sympathetic (hypogastric and lumbar sympathetic chain), and (3) somatic (pudendal) nerves.6 After leaving the spinal cord, these nerves travel jointly through the pelvic plexus and cavernous nerve to the genitalia (Fig. 14.1). The genital structures of both men and women respond with increased vasocongestion and neuromuscular tension and become engorged with blood (tumescent) via smooth muscle relaxation in the erectile tissues. Nitric oxide (NO) is the primary neurotransmitter responsible for smooth muscle relaxation in both sexes. While neuronal NO (nNO) is of major significance in the sexual response, NO is also generated from healthy endothelium (eNO). Genital arousal consists of penile erection in men. In women, there is vulvar swelling, clitoral engorgement, and vaginal lubrication and accommodation. In men, a stocking-like elastic structure (tunica albuginea) surrounds the erectile corporeal bodies (corpora cavernosa) and veins pierce through it to drain the cavernosa. When the tunica is stretched by the expanding corporeal bodies, venous outflow is stopped by kinking of the veins, allowing for increased intracavernosal pressure to build and penile erection to occur (venoocclusive mechanism). Penile rigidity is enhanced by pelvic floor contraction. Women have a much thinner tunical structure around the clitoral bodies. Fig. 14.1 Although both excitatory and inhibitory descending signals from the brain are possible, an excitatory signal must dominate in order to remove the supratentorial inhibition that exists on spinal sexual reflexes. Such signals are transmitted to the genitalia through two pathways: the “psychogenic pathway,” rising from the sympathetic spinal cord center at T10–L2, and the “reflexogenic pathway,” starting from the intermediolateral nuclei from S2–S4 and exiting as the nervi erigentes. Both sympathetic (hypogastric nerve and plexus) and parasympathetic nerves unite in the pelvic plexus. The pelvic plexus contains parasympathetic, sympathetic, and afferent somatic fibers, and in men, the cavernous nerve is the largest nerve exiting the pelvic plexus. For erection, para-sympathetic dominance must prevail at the penile tissue level to promote smooth muscle relaxation via nitric oxide release: after spinal cord injury (SCI) the reflexogenic pathway provides the parasympathetic innervation if the psychogenic pathway is damaged. Sympathetic fibers from the psychogenic center (via hypogastric nerve), which normally signal smooth muscle contraction (primarily via noradrenalin), also carries pro-erectile fibers as evidenced in the SCI population who have damaged their sacral cord yet are still able to retain some erectile potential. Interneurons in the spinal cord connect the psychogenic and reflexogenic pathways in a reinforcing way: interneuronal spinal cord damage can also affect erectile quality even if both pathways remain intact. The pudendal nerves from S2–S4 comprise both motor efferent (neuronal cell bodies in Onuf’s nucleus) and sensory afferent fibers. The reflex component of the reflexogenic pathway consists of an afferent sensory component from the genitalia entering the sacral cord via the pudendal nerve, and an efferent component comprised of parasympathetic signals (nervi erigentes), and somatic signals (pudendal nerve), the latter of which is responsible for the contraction of the striated pelvic-perineal muscles, including the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus. Local genital arousal and vasocongestion is primarily under parasympathetic dominance; sympathetic stimulation will cause detumescence of genital structures. With higher arousal levels, orgasmic release (often accompanied by ejaculation in men) can be experienced if the physiological orgasmic threshold is crossed.6 The ejaculation reflex, primarily a sympathetic phenomenon, consists of seminal emission and propulsatile ejaculation, and propels sperm and seminal fluid (semen) distally out the urethral opening. Orgasm is the pleasurable peak feeling of sexual release and may be initiated from genital stimulation (genital orgasm) or from erogenous zones outside the genitals, including the brain (nongenital orgasm). However, a satisfying sexual experience is not dependent on orgasmic ability. Genital arousal is controlled by two distinct pathways: the psychogenic pathway located between T10 and L2 in the spinal cord, and the reflex pathway, located in the sacral (S2–4) cord. There is also some evidence that the vagus nerve may be involved in orgasm in women with SCI.7 Studies have shown the neurological ability to achieve psychogenic arousal after SCI can be predicted in both men and women by the combined degree of preservation of surface sensation to pinprick and light touch in the T11–L2 dermatomes.8 The natural ability of men with SCI (without using medication or assistive devices) to have an erection from either psychogenic or reflexogenic sources will depend on the level and completeness of the lesion. This ability is reported to be 62%, but about two thirds of men with SCI find their erections either to be unreliable or to be of short duration.9 Because of this, at least 60% report the use of some form of erection enhancement.9 Ejaculation potential depends, like erection, on the level and completeness of the lesion, but it is more likely in men who have preserved bladder and bowel control, spasticity, the ability to achieve a psychogenic erection, the ability to retain an erection, and when there is direct penile manipulation versus vaginal intercourse.6,10 Unless significant increases in blood pressure (BP) occur with sexual stimulation, ejaculation is unlikely to happen.10 The chance of either reaching ejaculation or experiencing orgasm after SCI appears to be modestly enhanced by the utilization of oral erection medications11 or sympathomimetic drugs such as mididrone.10 Approximately 40 to 50% of men and women after SCI are able to reach either self-defined or laboratory-recorded orgasmic release, although the length and intensity of stimulation required to reach orgasm may exceed preinjury requirements.8 In both sexes, having a complete versus incomplete injury (regardless of level of injury), having an intact sacral reflex arc, and having genital sensation are more predictive of orgasm.6,8 For men, orgasm is more likely when ejaculation is possible, although some men are orgasmic without ejaculation after SCI.8 Newer studies are finding that, for some men with SCI, the pleasurable or orgasmic experience at ejaculation is related to the phenomenon of autonomic dysreflexia (AD). AD, a potentially dangerous condition of episodic hypertension triggered by noxious and nonnoxious afferent stimuli below the level of the SCI lesion that is well known in the SCI population,6 can also result in such unpleasant symptoms (severe headache, nausea, sweating, etc.) that sex is not enjoyable or is even avoided. That said, researchers have found that few orgasmic sensations are reported when AD is not produced with sexual stimulation, pleasurable climactic sensations are reported when mild to moderate AD occurs, and unpleasant or painful sensations are reported with severe AD.12 While studies have not yet been completed on women with SCI, the data from men with SCI, which encourage sexual rehabilitation emphasizing self-ejaculation, self-exploration, and cognitive reframing to maximize the perception of sexual sensations and climax, may well apply to women with SCI. Compared with women with SCI, men’s fertility is significantly affected because erectile function, ejaculatory ability, and semen quality are all compromised secondary to the neurological changes following SCI. In fact, at least 90% of men with SCI do not have the ability to father a child through the act of sexual intercourse13,14 given that anejaculation (lack of seminal emission or propulsatile ejaculation) is common. Other ejaculatory dysfunctions (e.g., retrograde ejaculation, etc.) can also occur after SCI.14 Methods of sperm retrieval have been devised for men with SCI. Ejaculation can be provoked either by the use of powerful vibrators, which provide strong afferent stimulus to the spinal cord to trigger the efferent ejaculatory reflex (penile vibratory stimulation [PVS]), or by “jump starting” the efferent component of the ejaculatory reflex by the use of periprostatic electrical stimulation via an anal probe (electroejaculation [EEJ]). Cumulative success rates of ejaculation of ∼ 86% have been reported using either PVS or EEJ in men with SCI,15 but they have more recently been found to be up to 100% when all sperm retrieval methods, including surgical aspiration, are utilized.10 Finger massage of the prostate and seminal vesicles can also mechanically express stored sperm that can then be used for insemination when PVS or EEJ is not available, but it is not clear whether this is yet indicated in men with SCI.16 Surgical sperm retrieval methods (where sperm are surgically retrieved from the internal accessory glands) are also possible, but the use of this in men with SCI when other less invasive and costly methods are available, is controversial.16 PVS is the first-line treatment for anejaculation for men with SCI and is most successful in men with SCI above T10 (88% success rate) where the sacral reflex is preserved as compared with men with a level of injury at T11 or below (15% success rate).17 Since there is an art and a science to PVS, the more experienced clinicians or clients have better ejaculatory success; however, the vibrator itself seems to be the critical element. Low amplitude, low frequency vibrators (obtained commercially) are not as successful as a vibrator of high amplitude (i.e., 2.5 mm excursions of the vibrating head) and frequency (i.e., speed of 90 to 100 Hz) such as the Ferticare (Multi-cept APS, Denmark). The vibrator is placed on the frenulum or “signature spots” found on the glans penis to trigger ejaculation, usually within minutes.6 If PVS is initially unsuccessful, additional stimulus can be tried to facilitate ejaculation, such as the application of two vibrators (“sandwich technique”), use of abdominal electrical stimulation (AES) in addition to PVS,17 or the use of phosphodiesterase V inhibitors (PDE5i) that may encourage ejaculation after SCI.11 The use of mididrone, a sympathomimetic drug, with or without PVS, is also helpful to induce ejaculation in some men but should be utilized with caution in men who experience AD because it can increase AD severity.10 Those individuals who do not respond to PVS or other efforts should then be referred for EEJ. An electrical current, delivered through an anal probe with the man in a lateral decubitus or supine position, stimulates seminal emission. The Seager Electroejaculator (Dalzell Medical Systems, The Plains, VA) remains the only approved device for this procedure.14 The ejaculate is then milked through the urethra and collected and utilized for insemination techniques. Men with incomplete or lower injuries will require anesthetic for EEJ, whereas others may tolerate the procedure in an outpatient setting. It is imperative to note that, during both PVS and EEJ, men must be monitored for AD, especially if the lesion is T6 or above.6 Any man with SCI who wishes to pursue ejaculation utilizing a sympathomimetic medication or PVS at home for either fertility or pleasure reasons should first be evaluated for AD risk management with ejaculation in a clinic capable of continuous hemodynamic monitoring. AD can produce not only severe hypertension (and its concomitant cardiovascular risks, such as stroke)6 but cardiac arrhythmias as well.18 The use of prophylactic medication should also be considered prior to ejaculation attempts in those men prone to AD.14,19 Men with SCI have, from ∼ 2 weeks postinjury,16 permanent changes in their semen quality, with abnormal sperm motility and viability, although sperm count per se remains normal.16 Abnormal accessory gland function, possibly from dissinnervation of the prostate gland and seminal vesicles, may be the cause of abnormalities in the seminal plasma. It does not appear that elevated scrotal temperature, infrequency of ejaculation, duration of injury, or methods of bladder management account for the lowered sperm motility, but rather that immune regulatory dysfunction and numerous abnormalities in the seminal fluid, including various toxic biochemical substances and abnormal levels of white blood cells (leukocytospermia), appear to be the culprits.16 A treatment utilizing monoclonal antibodies to interfere with the action of damaging levels of cytokines in the seminal plasma of men with SCI may represent a future intervention to assist with poor semen quality after SCI.20 Where possible, if the semen can be safely obtained and it is of adequate quality, the least invasive reproductive technology during well-timed ovulatory cycles should be utilized, that is, the use of home intravaginal insemination (IVI) via syringe transfer to the vagina, or by intrauterine insemination (IUI) where the semen is specially prepared and placed directly into the uterus. Factors such as very poor semen quality or advancing age or fertility issues of the female partner encourage the expedited use of higher technology, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), where the sperm and oocyte are placed together to fertilize in a petri dish, and the ensuing embryo(s) are placed into the uterus or cryopreserved for a later cycle. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), where a single sperm is injected directly into the egg, can be utilized to force fertilization. Such high-level interventions (i.e., using ejaculated or fresh testicular sperm in an ICSI cycle), may result in better conception rates per cycle.21 However, decisions regarding method of retrieval and insemination must also include a cost–benefit ratio.14 A review of pooled fertility data revealed a pregnancy rate of 51% and live birth rate of 40% in partners of men with SCI.15 It appears that pregnancy outcomes (utilizing IUI, ICF, or ICSI) using sperm from men with SCI seem to be similar to those using sperm from non-SCI men with male-factor infertility: the reader is directed to an excellent review of sperm retrieval, semen quality, and pregnancy rates in partners of men with SCI.16 Female fertility is usually not affected by SCI. Transient hypothalamic pituitary hypogonadism with associated amenorrhea (lasting an average of 6 months) occurs in ∼ 40% of women and is not associated with the extent of the neurological deficit.22 However, menstruation almost always resumes, and somewhere between 14 and 20% of women with SCI subsequently have at least one pregnancy.22,23 Few accessible examination beds have resulted in women with SCI, in general, receiving less gynecological care, including fewer mammograms and PAP smears.24 Birth control is more of an issue than fertility for women after SCI. For example, barrier methods (diaphragms and condoms) may not be practical for women with compromised hand function or self-care potential. The use of birth control pills (BCPs) is generally not favored in women with SCI due to the thrombotic risk secondary to estrogen, but they are used in selected women with SCI who are at lower risk (more mobile, etc.). Women with SCI who have concomitant brain injury and/or memory issues would not be appropriate candidates for the daily BCP. Progesteroneonly methods of birth control can result in unpredictable bleeding or spotting, and there is some speculation about the use of depot-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) and skeletal health, particularly in women with SCI, who are already at risk for osteoporosis.25 Perforation or expulsion of intrauterine devices (IUDs) may go unnoticed in women with SCI or may only present symptomatically as spasm or AD. Unfortunately, inadequate information about birth control and pregnancy is common among young women with SCI (only 10% receive adequate information during rehabilitation), and about half of women with SCI in their childbearing years do not desire pregnancy.26 It has also been reported in a study of 128 women with SCI that of those who became pregnant, 40% chose to terminate.22 During pregnancy, chronic bacteriuria and recurrent urinary tract infections are common, and preventative strategies are not well delineated.27 Bowel emptying is delayed, and perineal hygiene becomes more difficult. Transferring difficulties increase due to alterations in the center of balance, increased spasticity, and weight gain. There is an increased risk of skin breakdown and pedal edema, thrombophlebitis, and deep vein thrombosis. Post-partum depression is also more common in women with SCI.26 Since the uterus is innervated from T10 through L1, preterm delivery is a risk in about one third of women with SCI, and about one fourth of women with SCI are not able to feel preterm labor.26 Premature cervical dilation, premature labor, and small-for-date infants (etiology unknown) are more common in women with SCI than in women without SCI, but the risk of spontaneous abortion is the same in both populations.27,28 Autonomic dysreflexia is a serious complication in 85% of women with complete or incomplete lesions at or above the T5-6 level. During labor, AD can result in uteroplacental vasoconstriction with secondary fetal hypoxia and bradycardia, as well as put the mother at risk for stroke and other hypertensive complications.6,26 Because of this, labor requires a multidisciplinary team approach, with the capacity for hemodynamic monitoring to distinguish preeclampsia from AD, anesthetic capacity, and the ability to reposition the woman every few hours during labor to prevent skin breakdown. Although most women with SCI deliver vaginally, there is a higher risk of cesarean section, and vacuum and forceps extraction, especially if there is AD or fetal distress.26 Breast feeding may be a problem in women with injury above T4 due to loss of suckling afferent pathways to facilitate letdown reflex, and lactation may cease after 3 months or so because of inadequate response to nipple stimulation.28 Although sexual satisfaction is reportedly lower in both men and women after SCI, three fourths of persons after SCI are satisfied with life circumstances: predictors include having a good relationship with a partner, having some mobility, having fewer SCI consequences (i.e., fewer bladder, bowel, skin, and AD complications) and experiencing mental well-being.3,6 The multidisciplinary utilization of a Sexual Rehabilitation Framework is very helpful to look at medical or psychological factors that impede or improve sexual and reproductive function, and may serve to prevent the development of unnecessary sexual and fertility anxieties. Regardless of the health care discipline of the clinician, the framework provides the opportunity to outline appropriate therapeutic options in line with the client’s priorities: particular aspects of the sexual or reproductive concerns can then be addressed according to the clinician’s expertise and the others referred. Components of the framework and potential therapeutic suggestions are noted in the following paragraphs. Sexual drive (libido) has a biological (urge to seek out sexual activity) and motivational component (physical or emotional sexual payoff). Managing biological or medical factors, such as replacement of hormones, treating depression, addressing incontinence or fatigue, or altering medications that interfere with sexual function, can greatly improve sexual motivation and payoff. Psychological and relationship issues affecting sexual motivation also need to be addressed. Once the main source of dissatisfaction is identified, addressing its etiology can direct therapy to the appropriate resource. The following areas should be assessed: (1) genital arousal (erection capacity in men and awareness of pelvic fullness or vaginal lubrication in women), (2) ejaculation ability in men, (3) orgasmic potential in both sexes, and (4) pain with sexual acts. Treatments for genital arousal difficulties include the use of PDE5i that are reliant on the availability of both nNO and eNO sources in the genital area. Most men with SCI (> 80%) will respond well to the choices of PDE5i, which include sildenafil (Viagra, Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) as needed and vardenafil (Levitra and Staxyn, Bayer Pharmaceuticals Corp., Pittsburgh, PA), whose maximal effect is from 1 to 4 hours after it is taken, or the longer-acting (24 to 48 hour in SCI) tadalafil (Cialis, Lilly USA, Indianapolis, IN) as needed or Cialis Once-a-Day. Men with reduced nNO (lower cord injuries) or eNO (smokers, men with hyperlipidemia) will not respond as well to the PDE5i. Other choices for erection enhancement include the use of a vacuum device (VED). The VED consists of a cylinder (placed over the flaccid penis) and a pump that generates a vacuum, drawing blood into the penile tissues to create an erection that is maintained by a penile ring placed at the penile base. If an erection can be attained but not maintained, the use of penile rings alone can be tried. In both cases the ring should not be left on for more than 45 minutes: this can be a potential hazard in men who cannot feel their penis. Intracavernosal (penile) injections of single or mixed medications (prostaglandin E1, papaverine, and phentolamine) that directly relax the cavernosal smooth muscle are very effective but run the risk of priapism, so appropriate technique training and dosing instructions are necessary. Surgical penile prostheses destroy the cavernosal tissue so are only utilized when reversible methods prove unsatisfactory or there are other bladder management issues where a prosthesis for erection may be helpful. For women with SCI, fewer options exist, and studies are sparse. Small but significant improvements in subjective arousal in women with SCI have been seen with sildenafil, especially when accompanied with manual and visual stimulation.29 EROS-CT (Clitoral Therapy Device, Urometrics Inc., St. Paul, MN), a small, battery-powered vacuum device designed to enhance clitoral engorgement by increasing blood flow to the clitoris, is the only US Food and Drug Administration cleared-to-market device available by prescription to treat female sexual dysfunction.30 Theoretically, for some women with SCI, there may be some benefit in clitoral responsiveness, and there may be an additional training effect from EROS-CT on the pelvic floor in those women who have retained a bulbocavernosus reflex, which in turn may reinforce remaining sacral reflexes. Ejaculation disorders are treated by various methods noted under fertility. Orgasmic potential in both sexes can be improved by several techniques that increase genital stimulation, improve awareness of sensate areas, or allow for cerebral inputs to be appreciated at a higher level. Men and women should be encouraged to learn new body maps of erogenous areas, and to learn and practice mindfulness techniques around sexual inputs. While the use of relaxation, meditation, fantasy, recalling positive sexual experiences, breathing, and “going with the flow” can improve orgasmic potential, being with a trusted and long-term partner is the most predictive factor in orgasmic attainment after SCI.31 Vibrators are commonly used externally on the clitoris or internally on the cervix, but can also provoke AD in susceptible women. Persistence with physical stimulation in the context of security and intimacy can lead to reinforcement of new neural pathways and contribute to neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity depends on focused repetition of a new task, attention to signals occurring in the moment, and an openness and positivity in their interpretation. Health care professionals can assist men and women with SCI in this process by actively intervening with therapeutic suggestions to reduce medical interferences, such as pain, spasticity, AD, and incontinence; this will reduce the distractions and allow the freedom to focus. A full description of the pros and cons of therapies for sexual dysfunction in men and women with SCI is available in other readings.9,19,32 Assessment is needed regarding questions and expectations around fertility and contraception. Some women with SCI feel they are less fertile than they were preinjury or that they are not capable of pregnancy, labor, or parenthood. During pregnancy, multidisciplinary attention to the consequences of SCI noted earlier is essential. Men need to be assessed for ejaculatory capacity and sperm quality, whether the purpose be for fertility or contraception. It is important to preserve the client’s parenting rights while addressing the realistic issues of physical accessibility and emotional energy parenting requires. Many medical issues specific to having a SCI can impede sexual function. Therapies should be directed at reducing the interferences, with various disciplines involved in such management. This may be transient or chronic, but it is common enough for appropriate assessment and treatment to be done routinely. Depression will negatively affect all aspects of sexual functioning, as can treatment for depression (e.g., selective serotonin re-up-take inhibitor medication). Spasm can be necessary for mobility or transferring, but it can also impede sexual activities. Spasticity is noted to occur 26 to 38% of the time that a person with SCI is engaged in sexual activity.3 Although the use of antispasmodic medication can improve quality of life, it can also interfere with the sexual spinal cord reflexes: alternately, some men use ejaculation as a means to reduce spasm for several hours.33 Careful questioning around symptoms of AD should be done with the knowledge that a significant portion of AD is silent but not benign.34 Unless a proper clinical assessment is done, both the client and the medical professional can be falsely reassured that an asymptomatic client does not experience significant AD (hypertension or bradycardia). The use of a portable inflatable blood pressure (BP) cuff during daily activities can provide valuable information regarding BP changes, including those during private sexual activity. AD interfered with the motivation to be sexual in 28% of women and 16% of men in a recent survey.2,9 AD can be triggered with arousal as well as orgasm, and the occurrence of AD during typical bladder or bowel care was a significant variable predicting the occurrence and distress of AD during sexual activity.3 Preventative medication for AD (prazocin, nifedipine, etc.) can improve the motivation to be sexual or pursue fertility.6 Pain is counterintuitive to relaxation and sexual arousal. Medication should be taken at a time to maximize its effectiveness prior to sexual activity. During physical therapy rehabilitation, bed positioning can be explored to see whether specific support cushioning may prove helpful for reduction of pain or spasm during private sexual activity. Several medications can affect sexual function.35 Notably in the SCI population, antidepressants (which can suppress libido and interfere with arousal and orgasmic capacity), anticholinergics for bladder function, and drugs that reduce testosterone levels (cimetidine, spironolactone, etc.) can affect sexual function potential. Antispasmodics, such as intrathecal baclofen, have been noted to interfere with erection and ejaculation in men (and possibly interfere with orgasm in women), and cardiac medications can interfere with already compromised autonomic functions.6 The timing, reduction, or substitution of medications that affect sexual function should be attempted.35 Sensory and motor potential is critical in the assessment of sexual function. The ability to caress, hold, or position a partner depends on muscle strength and core balancing abilities. Transferring or turning independently in a bed needs to be assessed and assistive devices recommended by therapists as needed. Positioning cushions are now on the market. Sensory mapping (body mapping) needs to be done by the client (and/or partner) to understand what areas are insensate, what have some (or even high) arousal potential (i.e., often a zone around the area of injury), and what areas are to be avoided due to hypersensitivity. This body mapping is a critical learning stage in sexual rehabilitation. The use of sexual aids such as feathers, massage oils, vibrators for genital and nongenital use, and the use of fantasy are all part of remapping the brain to recognize new or different stimuli as “sexual,” even if they had not been tried pre-injury. This exploration assists with acceptance of and positive feelings about the “new” post-SCI sexual body. A helpful free manual for “hands-on” types of options for persons with disability is called PleasurAble, and is downloadable from the Disability Health Resource Network (www.dhrn.ca) under Disability Resources. One the most often reported and distressing issues around sexuality post-SCI is that of bladder and bowel incontinence, or the fear of such, during sexual activity. Although a survey noted that concerns around bladder and bowel during sexual activity were not strong enough to deter the majority of the population from engaging in sexual activity, in the subset of individuals who were concerned about bladder or bowel incontinence during sexual activity this was a highly significant issue.3 If the difficulties are significant enough, or the management issues are too cumbersome, delay in or withdrawal from sexual activity can occur. Assertive attempts to manage urinary incontinence issues by medications, intermittent catheterization, or even the consideration of bladder augmentation or continent urinary diversions may need to be examined. Diligence in reduction of urinary tract infections (UTIs) is also important for sexuality and fertility. Bowel management issues can delay or interfere with sexual enjoyment as well; bowel routines and reliable continence are paramount for the promotion of sexual activity. Dealing with SCI sequelae (altered body image, diminished independence, continence, hygiene, etc.) can alter one’s sense of sex appeal and sense of masculinity or femininity. Loss of confidence or former abilities at work or athletics, role reversal among partners, and the lack of support or loyalty of friends, family, and employers can further drain self-esteem. These specific issues need to be addressed to turn negatives into positives, and persistence with self-sexual exploration can realign the feeling of sexual wholeness, albeit in a new body. The context in which sexual activity is occurring (or not occurring) is critical in the evaluation of partnership potential. Clinicians need to initiate these discussions around partnership and peer counseling because they can be extremely useful in sexual adjustment.24 Constructing a chart for the Sexual Rehabilitation Framework is a practical method to assess sexuality and fertility in persons with an SCI or any disability or chronic illness (Table 14.1). For example, a 36-year-old married man with C6 complete quadriplegia of 3 years duration may have an assessment that looks like the example in Table 14.2. The same chart could be done for a 22-year-old single woman with incomplete paraplegia in a wheelchair: her issues may be about her potential to become genitally aroused and to achieve orgasm, continence issues around sexual activity, mobility to social events and meeting partners, safe birth control options, and whether she could conceive and carry a normal pregnancy to term and vaginally deliver. A large-scale cross-sectional questionnaire inclusive of 350 respondents over four European countries identified sexual activity as the area of greatest unmet need for persons with SCI.36 Based on these stated priorities, the need for sexual and fertility rehabilitation is high, but the available studies addressing these issues are relatively low. Treatment of sexual disorders in men and women with SCI is most successful when clients and clinicians follow three principles of sexual rehabilitation4: Although the physiology of sexual response has been relatively well mapped out by laboratory studies, the many facets involved in the interpretation of arousal and pleasure are not. Unlike motor and sensory recovery, sexuality after SCI has the potential to continue evolving long after the physical body has reached its maximum “somatic” recovery: this “sexual neuroplasticity” is best demonstrated by the stories provided by men and women with SCI and other neurological disabilities. Because it is well documented that improvement in quality of sexual health will lead to improvement in quality of life,3 and since dedicated men and women with SCI are excellent physiological models to answer our future questions about sexual potential, research efforts around sexual rehabilitation in this population must continue to be supported. Fortunately, there are newer resources addressing the area of sexuality and SCI, such as Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence (SCIRE) (www.icord.org/scire) and the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines on Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury that has been recently published by the Paralyzed Veterans of America (www.pva.org). Even more difficult issues, such as supporting sexual health and intimacy in care facilities, are available as guidelines for viewing.37 Table 14.1 Chart for the Sexual Rehabilitation Framework Sexual area Spinal cord injury effect Action plan and/or referral Sexual drive/interest Sexual functioning abilities Fertility and contraception Medical consequences of spinal cord injury Motor and sensory influences Bladder and bowel influences Sexual self-view and self-esteem Partnership issues (± parenting) Table 14.2 Example of a Chart for the Sexual Rehabilitation Framework of a 36-Year-Old Married Man with C6 Complete Quadriplegia of 3 Years Duration Sexual area Spinal cord injury effect Action plan and/or referral Sexual drive/interest Returned to preinjury level No action Sexual functioning abilities Problems with maintenance of reflex erection Anorgasmia First-line erectile dysfunction therapies: try PDE5i daily or as needed for patient preference; consider ring or injection if PDE5i failure Attempt ejaculation first Encourage cerebral arousal techniques Fertility and contraception Anejaculation Not an issue at present Trial of PVS by local expert. EEJ if PVS + AES failure. Maybe in future if ejaculating at home? Medical consequences of spinal cord injury Baclofen user History of autonomic dysreflexia Bladder health History of pressure sores Consider lower dose prior to sperm retrieval Prior to sperm retrieval, consider utilization of antihypertensives Reduce UTIs prior to fertility attempts Instruction in sexual positioning to avoid this by PT, OT, rehabilitative nursing Motor and sensory influences Spasm can interfere with sexual activity Poor hand function Lack of sexual feeling below injury, but painful hyperesthesia at injury line Have PT assess sexual positioning potential Have OT design assistive aids for ICI or ring placement if needed Learn body mapping to incorporate appropriate sensate/arousal areas Bladder influences and bowel influences Wants to have different bladder management around sexual issues Managed well around sexual activity Urology consult Use of condoms to prevent dripping Catheterization prior possible? No action Sexual self-view and self-esteem Feels physically “adjusted” but less masculine Not wishing to pursue at the present time Partnership issues (parenting) Some insecurity around relationship Wife in role of caregiver and intimate partner Psychology consult with wife regarding interpersonal relationships and fertility goals Boundaries around two issues need to be defined Abbreviations: AES, abdominal electrical stimulation; EEJ, electroejaculation; ICI, intracavernosal injection; OT, occupational therapist; PT, physical therapist; PVS, penile vibratory stimulation; UTI, urinary tract infection. Much more research in the area of sexual and fertility rehabilitation is needed. With the new International Standards to Document Remaining Autonomic Function after SCI,38 including those of Sexual and Reproductive Function,39 it is hoped the role of visceral, cardiovascular, and other autonomic contributions to sexual function and pleasure will be better delineated in the future. Furthermore, to adequately assess the complex issue of sexual health, it is recommended that future sexual health outcome measures include both quantitative and qualitative data as well as address several key issues identified by the men and women with SCI.24 The future improved quality of life for men and women with SCI will depend upon high-quality research in the area of sexual and fertility rehabilitation by dedicated professionals. Pearls

Sexuality and Fertility after Spinal Cord Injury

The Mind–Body Interaction

The Mind–Body Interaction

Neurophysiology of the Sexual Response

Neurophysiology of the Sexual Response

Sexual Function after Spinal Cord Injury

Sexual Function after Spinal Cord Injury

Changes to Fertility after Spinal Cord Injury

Changes to Fertility after Spinal Cord Injury

Fertility Issues in Men Following Spinal Cord Injury

Methods of Sperm Retrieval

Changes in Semen Quality and Insemination Options

Contraception, Fertility, and Pregnancy in Women Following Spinal Cord Injury

The Comprehensive Approach to Sexuality after Spinal Cord Injury

The Comprehensive Approach to Sexuality after Spinal Cord Injury

Sexual Drive or Sexual Interest

Sexual Functioning Abilities

Fertility and Contraception Concerns

The Medical Consequences of Spinal Cord Injury

Depression

Spasticity

Autonomic Dysreflexia

Pain Management

Medications

Motor and Sensory Influences

Bowel and Bladder Issues

Sexual Self-View and Self-Esteem

Partnership Issues

Future Expectations

Future Expectations

Maximize the remaining capacities of the total body before relying on medications or aids (learning new body maps, breathing, visualization methods, mindfulness exercises, etc.).

Maximize the remaining capacities of the total body before relying on medications or aids (learning new body maps, breathing, visualization methods, mindfulness exercises, etc.).

Adapt to residual limitations by utilizing specialized therapies (use of vibrators, training aids, PDE5i, vacuum device aids, etc.).

Adapt to residual limitations by utilizing specialized therapies (use of vibrators, training aids, PDE5i, vacuum device aids, etc.).

Stay open to rehabilitative efforts and new forms of sexual stimulation, with a positive and optimistic outlook.

Stay open to rehabilitative efforts and new forms of sexual stimulation, with a positive and optimistic outlook.

The use of the Sexual Rehabilitative Framework serves to demystify the area of sexual issues related to SCI into manageable options that fit into the context of that person’s life. It also demonstrates the multidisciplinary nature of the sexual health/fertility rehabilitative team.

The use of the Sexual Rehabilitative Framework serves to demystify the area of sexual issues related to SCI into manageable options that fit into the context of that person’s life. It also demonstrates the multidisciplinary nature of the sexual health/fertility rehabilitative team.

The issues of pleasure should be considered as legitimate as those of sexual function and fertility. Encouragement utilizing the sexual rehabilitation principles will result in more gratifying experiences for men and women with SCI than an approach oriented toward a more medical solution.

The issues of pleasure should be considered as legitimate as those of sexual function and fertility. Encouragement utilizing the sexual rehabilitation principles will result in more gratifying experiences for men and women with SCI than an approach oriented toward a more medical solution.

Fertility is not affected in women with SCI as it is in men, but issues around pregnancy and delivery require special expertise to prevent unnecessary complications. Fertility options for men include successful sperm retrieval and assistive reproductive technology, allowing most men with SCI to become biological fathers.

Fertility is not affected in women with SCI as it is in men, but issues around pregnancy and delivery require special expertise to prevent unnecessary complications. Fertility options for men include successful sperm retrieval and assistive reproductive technology, allowing most men with SCI to become biological fathers.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine