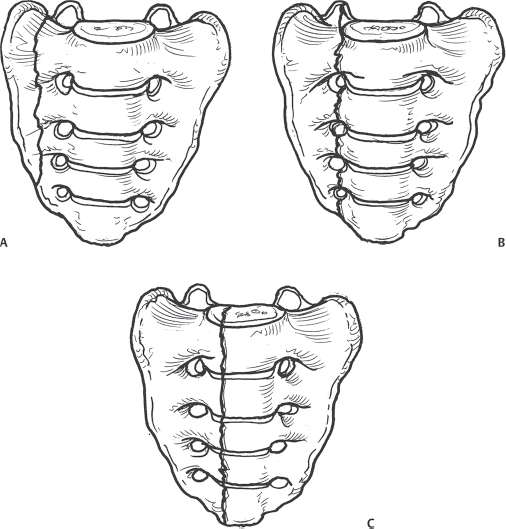

15 Fractures of the sacrum make up ~ 1% of all spinal fractures. The sacrum is formed by the fusion of the caudal spinal segments. It forms the key link between the axial skeleton (pelvis) and the spine. It includes both bony and ligamentous components that serve as a solid weight-bearing platform, protecting the lumbosacral spine (L4–S1), sacral (S2–S4) nerve roots, and iliac vessels. Sacral fractures follow a bimodal distribution. Injuries in younger patients tend to involve high-energy trauma, such as falls or motor vehicle crashes. These fractures are often associated with injuries to the pelvic ring and with other associated traumatic injuries. Injuries resulting in pelvic ring instability and widening of the pelvic ring can result in significant blood loss and require emergent treatment. In contrast, older patients most commonly sustain insufficiency fractures of the sacrum as a result of osteoporosis and osteopenia. These fractures are notoriously difficult to diagnose and may require computed tomography (CT), bone scanning, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to demonstrate the fracture. Sacral fracture patterns include vertical fractures, transverse fractures, and Uor H-shaped fractures. Denis et al. described vertical fractures in relation to the sacral foramina. In the Denis classification system, a zone I fracture (Fig. 15.1A) involves the bone lateral to the foramina. It is the most common (50%) type of injury and has a low incidence of neurologic or bladder injury. Neurologic injury occurs in ~ 6% of Zone I injuries and often involves the L4 and L5 nerve roots. Zone II fractures (Fig. 15.1B) traverse the sacral foramina and account for ~ 34% of the vertical sacral fractures. These injuries have a higher incidence of neurologic injury (28%), which most commonly involves the L5, S1, and S2 nerve roots. A zone III injury (Fig. 15.1C) is medial to the sacral foramina and may involve the central spinal canal. Denis reported this pattern in 16% of sacral injuries and found the highest prevalence and severity of neurologic injuries. Bowel and/or bladder control or sexual function was impaired in 76% of the patients with a zone III injury. Fig. 15.1 Vertical fractures of the sacrum as described by Denis et al. Grading is based on the relationship of the fracture to the sacral foramina. (A) Zone I. (B) Zone II. (C) Zone III. Transverse fractures commonly occur in the area between S1 and S3 and are often associated with bladder dysfunction, especially if displaced. Any sacral or posterior pelvic fracture with displacement of 1 cm or greater is considered unstable. U- and H-type fractures involve both a vertical and transverse component. These injuries are typically the result of high-energy trauma, more often than bony insufficiency. Insufficiency fractures are generally considered stable; however, U- or H-style fractures from high-energy trauma should be considered unstable until proven otherwise. Sacral fractures rarely occur in isolation. Therefore, it is essential to consider the possibility of a sacral fracture when patients have sustained high-energy trauma to the lower lumbar and pelvic regions. Vaccaro et al. discussed five basic principles when assessing a sacral injury. These include assessing for: (1) active bleeding, (2) an open fracture, (3) a neurologic injury, (4) fracture pattern, and (5) pelvic and spinal stability of skeletal injury. The physician should search for any signs of lacerations, bruising, tenderness, swelling, hematuria, and crepitus. In the setting of a severe pelvic ring disruption, severe soft-tissue injuries may be present and can be seen in the form of a palpable subcutaneous fluid mass, consistent with lumbosacral fascial degloving (Morel-Lavelle lesion). A rectal exam is mandatory to rule out internal lacerations and to assess rectal tone. In female patients, a vaginal exam must also be performed. A thorough neurologic exam is critical. It is important to assess the function of the lower sacral roots, rectal tone, and light touch and pinprick sensation along the perianal concentric dermatomes of S2 through S5, and elicitation of specific reflexes, including perianal wink and the bulbospongiosus and cremasteric reflexes. Pelvic ring stability should be evaluated manually. Anterior-posterior, inlet, outlet, and lateral pelvic radiographs should be obtained. If an L5 transverse process fracture is found, there is a strong chance of an associated sacral fracture. In addition, avulsion fractures of the ischial spine, asymmetry of sacral foramina, or cephalad migration of the affected hemipelvis are findings suggestive of sacral injury with severe ligamentous disruption. CT is helpful when a posterior pelvic ring injury is suspected. A dedicated sacral CT with fine cuts and sagittal/coronal reformatting will help in detecting and understanding the fracture pattern. MRI is helpful in cases with neurologic deficits or when trying to assess for an insufficiency fracture. Patients with insufficiency fractures are generally treated nonoperatively. Treatment includes assistive devices for ambulation, pain medication, and physical therapy. A subset of patients refractory to nonoperative care may be considered for sacroplasty: the injection of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) or bone cement, similar to vertebroplasty. For traumatic injuries, nonoperative management is indicated for nondisplaced and impacted sacral fractures in patients who are neurologically intact. This generally involves maintaining a restricted weight-bearing status on the affected side (non-weight-bearing or toe-touch) and allowing the fracture to heal. Patients with major pelvic disruptions who have evidence of hemodynamic instability may require the application of a pelvic binder or clamp, an anterior external fixator, skeletal traction, and/or embolization to control pelvic bleeding. More definitive management, to reduce and stabilize the disruption by internal fixation to the pelvic ring and sacrum, is indicated when the patient stabilizes. Patients with displaced sacral fractures involving the spinal canal may require direct decompression in addition to reduction and internal fixation of the sacral fracture, although early surgery is associated with an increased risk of hemorrhage, wound-healing complications, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. Those with evidence of sacral root stretch/avulsion fare best with early reduction and stabilization to allow an optimal environment for neural recovery. Stabilization of the sacrum and sacroiliac joints can be performed anteriorly or posteriorly. The most commonly performed procedure is the placement of iliosacral screws. When the fracture involves the foramina, fully threaded screws are generally used to avoid compression of the exiting nerves in the comminuted fracture site. The most important predictor of outcome is the neurologic status of the patient at the time of presentation. Following decompression/stabilization surgery, neurologic improvements in up to 80% of patients have been observed, although there is some degree of neurologic deficit. Denis et al. reported no improvement of bowel or bladder control in three patients in whom a transverse sacral fracture had been treated non-operatively. In contrast, all of five patients treated surgically had complete return of sphincter control. With instrumented procedures, Nork et al. reported successful results with percutaneous sacroiliac screw fixation in thirteen patients with Zone III injuries. Nonunion, continued or worsened neurologic deficit, loss of bowel or bladder control, severe bleeding, infection, anesthesia-related complications, wound and hardware complications, dural tears with subsequent formation of a pseudomeningocele, and visceral damage are all possible. Bayley E, Srinivas S, Boszczyk BM. Clinical outcomes of sacroplasty in sacral insufficiency fractures: a review of the literature. Eur Spine J 2009;18(9):1266–1271 PubMed In this meta-analysis of the results of sacroplasty, 15 papers including 108 patients were analyzed. Significant reduction in VAS pain scores was noted following sacroplasty (VAS 8.9 to 2.6). Cho CH, Mathis JM, Ortiz O. Sacral fractures and sacroplasty. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2010; 20(2):179–186 PubMed This is an excellent review of the use of sacroplasty for treating sacral insufficiency fractures and metastatic tumors of the sacrum. Denis F, Davis S, Comfort T. Sacral fractures: an important problem. Retrospective analysis of 236 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;227:67–81 PubMed This landmark retrospective study of 236 consecutive patients with sacral fractures in patients with 776 pelvic injuries describes the Denis classification system with typical injury patterns and projected outcomes. Kellam JF, McMurtry RY, Paley D, Tile M. The unstable pelvic fracture. Operative treatment. Orthop Clin North Am 1987;18(1):25–41 PubMed This overview of the importance of operative management of sacral fractures, and of the importance of obtaining an anatomic reduction, emphasizes the importance of appropriate preoperative evaluation, subsequent planning, and precise, technically skillful surgery done by an experienced surgeon. Lykomitros VA, Papavasiliou KA, Alzeer ZM, Sayegh FE, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA. Management of traumatic sacral fractures: a retrospective case-series study and review of the literature. Injury 2010;41(3):266–272 PubMed This is a review of the literature and presentation of a 16-patient case series. In this series, patients treated nonoperatively had better outcomes, which the authors attributed to the patients’ having less severe initial injuries. Nork SE, Jones CB, Harding SP, Mirza SK, Routt ML Jr. Percutaneous stabilization of U-shaped sacral fractures using iliosacral screws: technique and early results. J Orthop Trauma 2001; 15(4):238–246 PubMed This is a retrospective study of 442 patients with pelvic ring disruptions, thirteen with displaced U-shaped sacral fractures who underwent fracture stabilization via a fluoroscopically guided iliosacral screw. The authors concluded that percutaneous fixation diminishes potential blood loss and operative times and is an effective method of treatment. Rommens PM, Vanderschot PM, Broos PL. Conventional radiography and CT examination of pelvic ring fractures. A comparative study of 90 patients. Unfallchirurg 1992;95(8):387–392 PubMed This retrospective review of 90 patients with pelvic ring fractures compared the interpretation of conventional X-ray films and CT images. The authors demonstrated that pelvic ring evaluation with films alone is inadequate, with fractures of the sacral body and lateral part of the sacrum being overlooked. CT imaging is necessary in combination with radiography to improve diagnosis of sacral injuries. Routt ML Jr, Simonian PT, Swiontkowski MF. Stabilization of pelvic ring disruptions. Orthop Clin North Am 1997;28(3):369–388 PubMed This excellent review of pelvic ring injuries and their complications (including early hemorrhage, permanent nerve injury, and pelvic pain from deformity) discusses the treatment options for a disrupted pelvic ring as well as the treatment advantages and disadvantages. Roy-Camille R, Saillant G, Gagna G, Mazel C. Transverse fracture of the upper sacrum. Suicidal jumper’s fracture. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1985;10(9):838–845 PubMed This review of 13 patients with transverse fractures of the upper sacrum discusses fracture anatomy, presentation, and treatment options. The authors emphasize that sacral fractures are often missed in the setting of polytrauma, and that in the presence of perineal neurologic deficit or injury, appropriate exam and imaging are necessary. Sabiston CP, Wing PC. Sacral fractures: classification and neurologic implications. J Trauma 1986;26(12):1113–1115 PubMed The authors divide sacral fractures into three categories, including sacral fractures in conjunction with pelvic fractures, isolated lower-segment sacral fractures, and upper-level sacral fractures. They recommend conservative treatment, as they feel that associated neurologic deficit improves spontaneously. Strange-Vognsen HH, Lebech A. An unusual type of fracture in the upper sacrum. J Orthop Trauma 1991;5(2):200–203 PubMed This is an excellent review of the literature regarding sacral fractures. In addition, the authors define a fracture of the isolated upper sacrum and classify it as a special type—type 4 sacral fracture. Schmidek HH, Smith DA, Kristiansen TK. Sacral fractures. Neurosurgery 1984;15(5):735–746 PubMed This review of sacral fracture patterns and their neurologic involvement discusses treatment options for sacral fractures and also correlates vertical sacral fractures and patterns of pelvic injury. Vaccaro AR, Kim DH, Brodke DS, et al. Diagnosis and management of sacral spine fractures. Instr Course Lect 2004;53:375–385 This is an excellent overall review of diagnosis, imaging, and operative and nonoperative options for sacral fractures and the best overall treatment for the patient. Note: Unless medical circumstances dictate otherwise, operative management is typically recommended for all patients with neurological deficits or if there is a loss of posterior column integrity.

Sacral Fractures

![]() Classification

Classification

![]() Diagnosis

Diagnosis

![]() Treatment

Treatment

![]() Outcome

Outcome

![]() Complications

Complications

Suggested Readings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree