Chapter 32 Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Problems

Evaluation of Joint and Other Musculoskeletal Symptoms

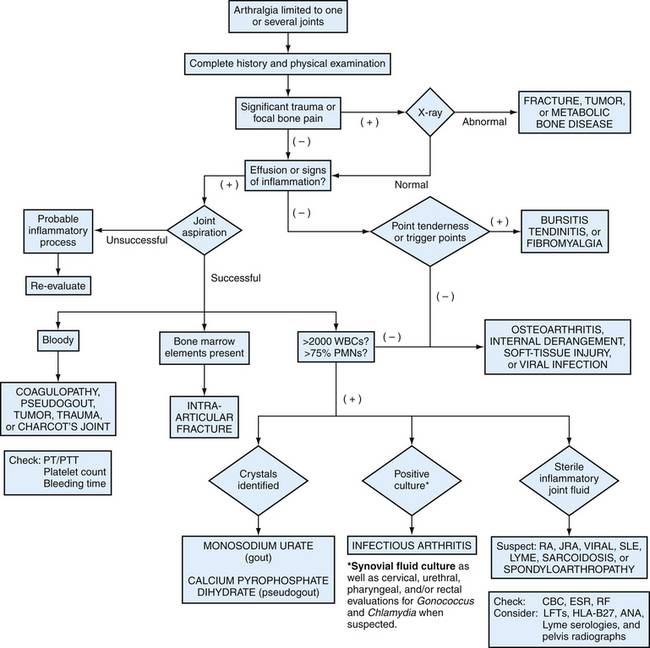

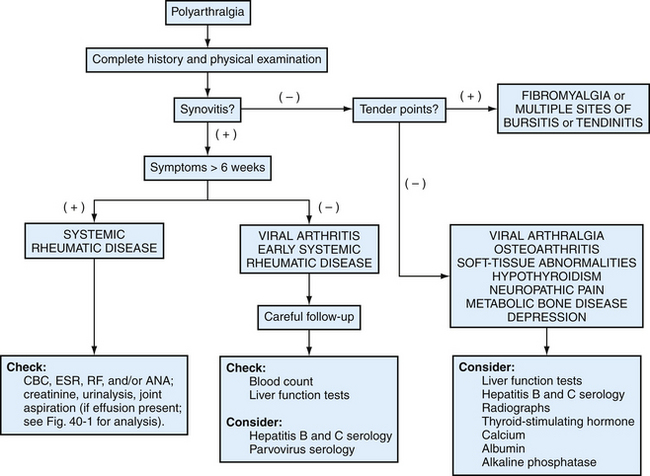

The number of involved joints and presence or absence of symmetry are criteria for further diagnosis of articular pain (Figs. 32-1 and 32-2). Monoarticular (one joint) or oligoarticular (several joints) arthritides can be caused by conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA), gout, pseudogout, or septic arthritis. Asymmetric polyarthritis occurs in ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s disease, and spondyloarthropathies. Symmetric arthritis, meaning that the same joint is affected on the contralateral side but not necessarily to the same degree, is characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome, polymyositis, and scleroderma. Fibromyalgia, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and predominantly psychological factors must be considered when pain is diffuse, not relatable to specific anatomic structures, or described in vague terms. (See also Chapter 30.)

Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, malaise, and weight changes are common chief complaints heard in a primary care office practice and often associated symptoms of specific rheumatic diseases. The patient’s functional ability, occupational history, and activities requiring repetitive joint movement, as well as the ergonomics of such activities, should also be considered routinely in initial and serial evaluations. How are the symptoms affecting the patient’s ability to perform self-care activities of daily living (ADLs) such as bathing, dressing, and eating? Is the patient able to do instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as buying groceries, cooking, using the telephone, and opening jars? Rheumatic disease can have a devastating effect on quality of life for both the patient and the family, with serious psychosocial and economic consequences. Therefore the physician should address effects on occupational, recreational, and sexual activities in the context of family and other support systems.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination should be performed on all patients presenting with joint pain, including examination of asymptomatic joints and other organ systems that might be involved. Joints should be examined for swelling, tenderness, deformity, instability, and limitation of motion. Comparisons with the patient’s contralateral side can be made in all these parameters, as well as with the physician’s joints as a control. Instability can be tested by moving adjacent bones in the direction opposite to normal movement and observing for greater-than-normal motion. Serial grip strength measurements can be made by asking the patient to squeeze a blood pressure (BP) cuff inflated to 20 mm Hg and recording the maximal grip force in millimeters of mercury. Signs of systemic disease include fever; weight loss; oral or nasal ulcerations; liver, spleen, or lymph node enlargement; neurologic abnormalities; rashes; subcutaneous nodules; eye iritis; conjunctivitis or scleritis; and pericardial or pulmonary rubs. Because of circadian changes in patients with RA, serial comparisons of the physical examination are more accurate if the time of day is also recorded. Using skeleton diagrams of joint involvement facilitates the recording of a comprehensive joint examination (Fig. 32-3).

Figure 32-3 Skeleton diagram for recording joint examination findings.

(From Polley HF, Hunder GG. Rheumatologic Interviewing and Physical Examination of the Joints, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 1978.)

Pathogenesis of Rheumatic and Other Musculoskeletal Diseases

As with most disease, research into the causes of rheumatologic and musculoskeletal diseases shows that the cause for each disease is actually multifactorial. Further identification of these factors will help the family physician and rheumatologist modify the course of disease and eventually perhaps even prevent them.

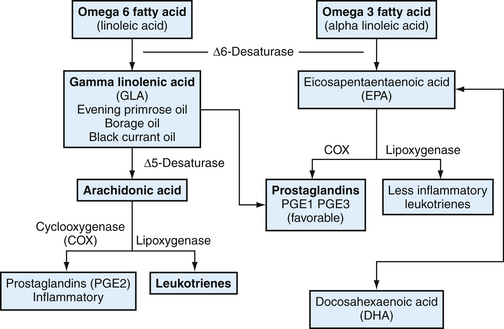

Infectious agents such as parvovirus B19, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), and streptococci (rheumatic fever) are all well-known causes of arthritides. Some speculate that dietary factors might contribute to autoimmune syndromes, and fasting or a vegan diet (or both) can lead to improvement in RA (Kjeldsen-Kragh et al., 1991; McDougall et al., 2002). The imbalance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids in the standard American diet (a ratio of 30:1, as opposed to the ratio of 1:2 that is thought to have been present in Paleolithic diets) is also postulated to contribute to a more inflammatory state. Omega-6 fatty acids are preferentially converted to more inflammatory prostaglandins such as arachidonic acid, whereas omega-3 fatty acids can be converted into eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which contribute to anti-inflammatory series-3 prostaglandin production (Fig. 32-4). Omega-3 fatty acids are useful in RA, showing a decrease in use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and decreased levels of pain (Oh, 2005).

Figure 32-4 Influence of omega-6 fatty acids and omega-3 fatty acids on inflammation.

(From Rakel R. Integrative Medicine. Philadelphia, Saunders-Elsevier, 2007.)

Laboratory Studies

Synovial Fluid Analysis

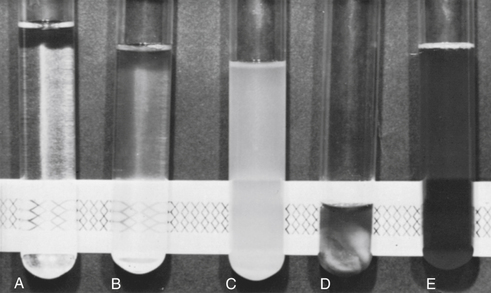

Synovial fluid analysis can be helpful in evaluating a febrile patient with an acute joint to rule out septic arthritis or acute monoarthritis. Synovial fluid should be analyzed for white blood cell (WBC) count differential, cultured, and tested with polarized light microscopy for crystals. Purulent synovial fluid with greater than 90% polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), low viscosity, and turbid clarity can be caused by infection or crystal arthropathy (gout or pseudogout). Urate crystals are needle-shaped and negatively birefringent; calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals are rhomboidal and weakly positively birefringent. Noninflammatory fluids generally have a clear appearance, normal viscosity, fewer than 2000 WBCs/mm3, and less than 75% PMNs (Table 32-1).

Table 32-1 Interpretation of Synovial Fluid Cell Count

| Leukocyte Count (WBCs/mm3) | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| <200 | Normal synovial fluid |

| <2000 | Noninflammatory fluid |

| >2000 | Inflammatory fluid |

| 2000-20,000 | Mild inflammation (e.g., SLE) |

| 20,000-50,000 | Moderate inflammation (e.g., RA, reactive arthritis) |

| 50,000 | Severe inflammation (e.g., sepsis, gout) |

| >100,000 | Sepsis, until proved otherwise |

WBCs, White blood cells; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

From Towheed TE, Hochberg MC. Acute monoarthritis: a practical approach to assessment and treatment. Am Fam Physician 1996;54:2239.

Synovial fluid analysis should always be performed on freshly obtained fluid. A simple bedside test is to attempt to read newsprint through the synovial fluid; newsprint can be read through noninflammatory fluid (Fig. 32-5). Traditional tests on synovial fluid that are of limited or no value include measurement of glucose, lactate, and protein levels; subjective determination of viscosity; mucin clot test (examining the friability of the precipitate formed by mixing synovial fluid with dilute acetic acid); and immunologic tests. When looking for crystals and infection, direct examination, Gram stain, culture, and WBC count with differential are the only tests worth performing on synovial fluid. Inflammatory synovial fluid must be considered secondary to infection until proved otherwise by culture. The presence of crystals in the joint does not exclude the possibility of joint infection.

Synovial biopsy can facilitate a diagnosis in some settings. Arthroscopy has greatly simplified the acquisition of synovial tissue. This might be helpful in the diagnosis of granulomatous disease or infiltrative processes such as lymphoma, metastatic disease, or amyloidosis (Klippel, 2001).

Imaging Studies

Plain radiographs are still the most common imaging studies done for evaluation and management of rheumatic diseases. Techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and radionuclide scintigraphy (bone scan) are being used more often, although costly and often unnecessary. Many arthritides have characteristic radiographic findings, but these techniques are not indicated for most patients with acute and new symptoms of SLE, gout, mechanical lower back pain, or RA, because radiographs are usually normal early in the course of the disease. Normal radiographs also do not rule out OA. In established RA, the physician might see periarticular osteoporosis, soft tissue swelling, and marginal erosions. Gouty erosions cause characteristic overhanging edges because of reparative changes. (See also Chapter 31.)

Functional Assessment

Arthrocentesis

Arthrocentesis is most helpful in diagnosing crystal-induced and septic arthritis. Synovial fluid analysis can also be helpful in ruling out the coexistence of two or more types of arthritis in a single patient and even in a single joint. RA might coexist with a septic joint, secondary OA, hemarthrosis, or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) disease. Hemarthrosis and bacterial infections usually occur in joints already damaged by arthritis. Arthrocentesis is a simple office procedure that can rule out bacterial infection in an acutely inflamed joint. Untreated or delayed treatment of infectious arthritis can cause rapid joint destruction, necessitating prompt diagnosis. A second line of treatment for RA should generally not be started until crystal arthropathy first has been ruled out. A physician is much more likely to harm a patient by not obtaining synovial fluid analysis when needed to make an accurate diagnosis. This is more common than the relatively rare occurrence of iatrogenic infection (particularly if proper sterile technique is used) or hemarthrosis (usually seen in patients with coagulopathies). The iatrogenic infection rate is generally estimated at 1 in 10,000, much less common than missed diagnosis of a septic joint. Anticoagulation therapy is not an absolute contraindication in the setting of acute arthritis.

Arthritis of Systemic Disease

Arthritis can be a component of many systemic diseases, including metabolic disorders, infections, malignancies, and various endocrine, hematologic, and GI diseases. Parvovirus B19 is responsible for erythema infectiosum and can also cause polyarthritis, especially in the hands, knees, and ankles. HIV infection sometimes causes symmetric polyarthritis, spondylitis, or acute oligoarthritis. Hepatitis B and C can cause acute symmetric polyarthritis in large and small joints. Inflammation in a few large joints and back pain are among the earliest symptoms of infective endocarditis in about 25% of patients with this disorder (Totemchokchyakarn and Ball, 1996).

Rheumatic Diseases

Osteoarthritis

Clinical Findings

Most OA is asymptomatic, an incidental finding on radiographs performed for other reasons. No treatment or further evaluation is indicated for asymptomatic OA. Early symptomatic OA is characterized by local pain of gradual onset exacerbated by using the involved joint. Pain typically worsens as the day progresses and is relieved by rest. There is less than 30 minutes of localized morning stiffness and no constitutional or systemic symptoms, and the gel phenomenon (stiffness after periods of rest and inactivity) resolves within several minutes of activity. Damp, cool, rainy weather often exacerbates symptoms because of changes in intra-articular pressure associated with changes in barometric pressure. Patients with OA of the knees might complain of buckling or instability, especially when descending stairs. OA of the hip can manifest as pain radiating from the groin and down the anterior thigh. OA of the neck might be felt in the neck, back, or upper extremities, causing pain, weakness, or numbness. As OA progresses, pain can become continuous, including at night.

Laboratory Studies

Clinical study criteria for OA classification are helpful as a means to standardize the diagnosis (see eTables 32-2 and 32-3 online). Although the diagnosis of OA can almost always be made by history and physical examination, definitive diagnosis can be helped by synovial fluid analysis, radiography, and normal ESR, ANA, and RF during symptomatic periods. Synovial fluid analysis of large-joint effusions can be used to exclude other processes. Joint effusions in OA typically show leukocyte counts lower than 1000 WBCs/mm3, predominantly lymphocytes (Table 32-2). Serum tests might be misleading because ESR rises with age and 20% of healthy older adults have positive RF levels. A greatly elevated ESR suggests a process other than OA. Although many have been identified, biochemical markers of OA are not generally useful to the practicing clinician at this time.

Table 32-2 Criteria for Classification of Idiopathic Osteoarthritis (OA) of Knee

| Clinical and Laboratory | Clinical and Radiographic | Clinical∗ |

|---|---|---|

| Knee pain plus at least five of nine: | Knee pain plus at least one of three: | Knee pain plus at least three of six: |

| 92% sensitive | 91% sensitive | 95% sensitive |

| 75% specific | 86% specific | 69% specific |

ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (Westergren); RF, rheumatoid factor; SFOA, synovial fluid signs of OA (clear, viscous, or white blood cell count <2000/mm3).

∗ Alternative for the clinical category would be four of six, which is 84% sensitive and 89% specific.

From Altman R, Asch E, Bloch G, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1039-1049, with permission of the American College of Rheumatology.

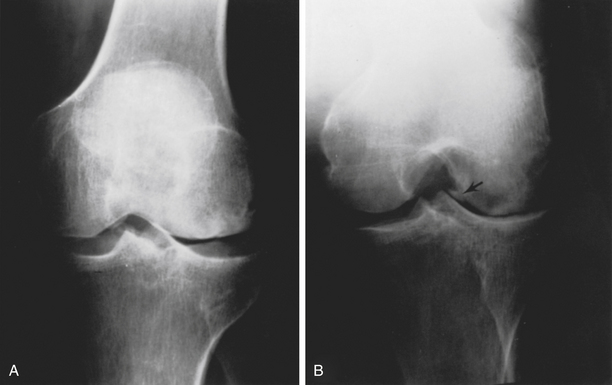

Imaging Studies

Radiographs are generally the first-line confirmation of the presence of OA. Treatment should not be based solely on radiographic abnormalities, however, given the frequency of asymptomatic joints demonstrating radiographic OA changes. OA changes include osteophyte formation, asymmetric joint space narrowing (defined as <3 mm on a weight-bearing knee), and subchondral bone sclerosis (Figs. 32-6 and 32-7). Later in the disease process, subchondral cysts with sclerotic walls might develop. Periarticular osteoporosis and marginal erosions suggest RA or some other inflammatory arthritis rather than OA. Patients with OA involving atypical joints (MCP joints, wrists, elbows, shoulders, or ankles) should be evaluated for an underlying disorder such as CPPD or hemochromatosis.

Figure 32-6 Osteoarthritis in the hand.

(From Resnick D, Yu JS, Sartoris D. Imaging. In Kelley WN Harris ED, Ruddy S, et al [eds]. Textbook of Rheumatology, 5th ed, vol 1. Philadelphia, Saunders, 1997, pp 626-686.)

Treatment

Treatment of OA includes pharmacologic therapy, nonpharmacologic therapy, and surgery. Before initiating treatment, a definitive diagnosis of OA must be made by careful history and physical examination. No currently available treatment has been shown to alter the natural history of the disease. Therefore, the goal of management of OA is primarily to relieve pain, stiffness, and swelling. The physician seeks to reduce limitation of motion and disability without causing iatrogenic side effects. Patients and their families must also be educated about the disease and their treatment options (Box 32-1).

Box 32-1 Options in the Management of Patients with Osteoarthritis

From Hochberg MC. Osteoarthritis: clinical features and treatment. In Klippel JH (ed). Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, 12th ed. Atlanta, Arthritis Foundation, 2001, pp 293-295.

First-line pharmacologic therapies for symptom control include acetaminophen, up to 1000 mg four times daily in the absence of liver disease, and traditional NSAIDs, beginning with ibuprofen. Because few RCTs studied differences in efficacy of NSAIDs, the initial choice is empiric. Therefore, relative safety, patient adherence, and cost should determine selection. Risk factors for upper GI bleeding with NSAIDS include age over 65, history of peptic ulcer disease or upper GI bleeding, concurrent use of oral corticosteroids and anticoagulants, and possibly smoking and alcohol consumption. Evidence suggests that NSAIDs are superior to acetaminophen for improving knee and hip pain from OA. No significant difference in overall safety was found, although patients taking NSAIDs were more likely to experience an adverse GI event (Towhead et al., 2006). Capsaicin (Zostrix) topical cream four times daily, formerly a first-line agent, now has been shown to have minimal benefit, especially when considering side effects that impair compliance (Mason et al., 2004). Combination therapy (NSAIDs with analgesics) may also be helpful. The addition of tramadol (Ultram, 200 mg/day) in patients responding to 1000 mg/day of naproxen has been shown to allow significant reduction (by half) in the naproxen dose needed without compromising pain relief (Schnitzer et al., 1999).

Other, less traditional therapies have received much media attention but not shown effectiveness. Cycles of three or more weekly intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid (viscous substance in synovial fluid that lubricates and protects joints) have been used, with partial success (Abramowicz, 1998a). Hyaluronate sodium (Hyalgan) and hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc) are FDA approved for OA of the knee. Onset of pain relief can take several weeks and can last for 6 months or longer. Meta-analyses of hyaluronic acid have shown minimal effectiveness versus placebo. The cost/benefit ratio favors therapies other than joint injection (Lo et al., 2003).

KEY TREATMENT

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Diagnosis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a clinical diagnosis made by careful history and physical examination. Laboratory testing can be confirmatory but is also misleading if not interpreted in context. Radiographic evidence of erosions appears only several months to a year after disease onset. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published useful criteria in 1987 for the diagnosis of RA (Table 32-3). Symptoms must be present for at least 6 weeks for initial diagnosis.

Table 32-3 American College of Rheumatology Revised Criteria for Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis (Traditional Format)

| Criterion∗ | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Morning stiffness | Morning stiffness in and around the joints lasting at least 1 hour before maximal improvement. |

| 2. Arthritis of three or more joint areas | At least three joint areas with simultaneous soft tissue swelling or fluid (not bony overgrowth alone) observed by physician. The 14 possible joint areas are right or left PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and MTP joints. |

| 3. Arthritis of hand joints | At least one joint area swollen as above in a wrist, MCP, or PIP joint. |

| 4. Symmetric arthritis | Simultaneous involvement of the same joint areas on both sides of the body; bilateral involvement of PIP, MCP, or MTP joints is acceptable without absolute symmetry. |

| 5. Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules over bony prominences or extensor surfaces or juxta-articular nodules regions, observed by physician. |

| 6. Serum rheumatoid factor | Demonstration of abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor by any method that has been positive in less than 5% of normal control subjects. |

| 7. Radiologic changes | Radiologic changes typical of rheumatoid arthritis on posteroanterior hand and wrist radiographs, which must include erosions or unequivocal bony decalcification localized to, or most marked adjacent to, the involved joints (osteoarthritis changes alone do not qualify). |

MCP, Metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

∗ Four or more criteria are needed for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Criteria 1 through 4 must be present for 6 weeks or longer. Presence of criteria is not conclusive evidence for the diagnosis of RA. Absence of criteria is not conclusively negative.

From Arnett FC. Revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Bull Rheum Dis 1989;38:1. Used with permission.

History

Less common presentations of RA include acute onset (which has the best prognosis) and palindromic RA, which is characterized by brief episodes of swelling of a large joint such as a knee, wrist, or ankle. Palindromic RA can therefore be easily misdiagnosed as gout.

Physical Examination

Joint Deformities

The synovitis of RA has many effects on cartilage, bone, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Cartilage and bone erode, and muscles and tendons shorten in response to chronic inflammation. Ligaments are weakened by collagenases released by inflamed synovium and pannus. Upper extremity joints (shoulder, wrist, elbow) are prone to more severe deformities, as previously noted, than knees and ankles because splinting (avoiding joint motion to minimize pain) is easier in these lower extremity joints. The decreased use of these joints leads to more destruction by tendon shortening and contraction of the articular capsule.

Imaging Studies

Radiography is indicated early when infection or fracture must be ruled out, the patient has a history of malignancy, the physical examination fails to localize the source of pain, or pain persists despite conservative treatment. Early RA might show only soft tissue swelling. Advanced destruction on radiographs should not be required to initiate disease-modifying therapy if a diagnosis of RA is strongly suspected clinically. In late-stage disease, radiographs might show marginal bony erosions, periarticular osteoporosis, and joint space narrowing, especially in the hands and feet (Figs.32-8 and 32-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree