Rehabilitation for Persons with Upper-Extremity Amputation

Margaret Wise

“Hands can do all kinds of things…change a tire, bake a pie, fly a kite or catch a fly, plant a seed and help it grow, point the way for feet to go.…Rough hands, smooth hands, plump hands, thin hands like wrinkled apple skin. Hands can do most anything…wear a ring, wear a glove, most important…hands can love!”1

Edith Baer

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

Rehabilitation after upper-extremity amputation

Human hands are wonderfully complex sensory and motor organs, capable of interpreting and interacting with the environment. The fine manipulative skills and intricate grasp patterns of the hand cannot be duplicated. When a hand is lost, the ability to perform normal daily tasks is greatly changed. Although a prosthesis cannot duplicate hand function, it can help substitute for basic grasp in the performance of normal daily activities and help maintain bilateral hand function.

This chapter discusses the treatment of adults with amputations, including aspects of acute care, preprosthetic care, basic prosthetic training, and advanced functional skills training. Working with patients with upper limb amputation can be quite rewarding for therapists, who must draw on manual and orthopedic skills, functional skills for training in activities of daily living, and counseling skills to respond to psychosocial needs.

Incidence and causes of upper-extremity amputation

The primary cause of upper-limb amputations is trauma; most commonly crush injuries, electrical burns that occur at work, or, in times of war, traumatic injuries sustained in combat. Congenital anomalies, infections, and tumors are other causes of amputation. Because upper-extremity amputations are typically occupation related, they primarily occur in young adults between the ages of 20 and 40 years; the ratio of men to women is 4:1. Dillingham2 reports approximately 18,500 new upper-extremity amputations per year. Just fewer than 2000 of these are at wrist level or higher. The ratio of upper-extremity amputations to lower-extremity amputations is 1:9.2,3

Classification and functional implications

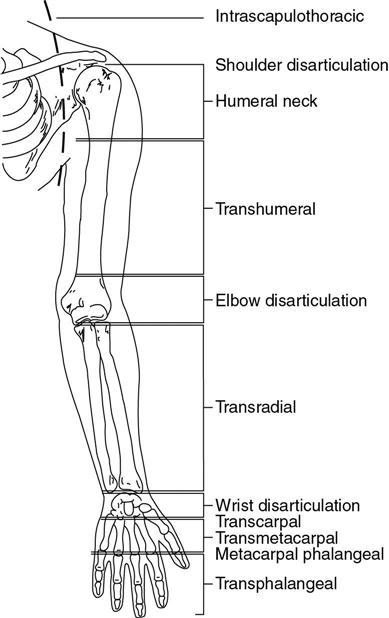

The remaining part of the amputated limb is referred to as the residual limb. The broad categories used to describe levels of upper-extremity amputation include transphalangeal, metacarpal–phalangeal, transcarpal, wrist disarticulation (styloid), transradial, elbow disarticulation, transhumeral, humeral neck, shoulder disarticulation, and intrascapulothoracic (Figure 31-1).2–5

Functionally speaking, the more proximal the level of amputation, the greater the loss of range of motion (ROM) and strength that results. Of particular importance are the loss of supination and pronation in amputations approaching the mid-forearm and the loss of shoulder rotation as the amputation approaches the axillary fold. Although a longer residual limb provides better mechanical advantage for prosthetic use, limb length does not always correspond to better prosthetic function. The length of the residual limb in an elbow disarticulation or long transhumeral length amputation, for example, limits the space available for an electric elbow unit and affects both cosmesis and function of the prosthesis.

Stages of rehabilitation

The rehabilitation of individuals with upper-extremity amputation can be divided into four phases: acute care, preprosthetic rehabilitation, basic prosthetic training, and advanced functional skills training. Although certain goals and activities are unique to each phase, the ultimate goal is to enhance function so that patients with upper-extremity amputation can return to the activities most important to them.

Acute Care

Often the most pressing issue in the first days to weeks after traumatic upper-extremity amputation is saving the patient’s life. The patient may return to the operating room several times for surgeons to clean the wound or perform revision surgery. The patient usually has intravenous lines for antibiotics and pain medications; special infection control procedures may also be in place. The patient may not be fully alert or even have full recollection of what took place the first weeks after injury.

The initial goals of therapy may be quite basic and must be modified to be appropriate to the patient’s medical status. Goals of the acute phase of rehabilitation include the following:

• To develop rapport with the family and patient.

• To control pain effectively.

• To establish a strategy for effective edema control.

• To preserve as much passive ROM of the residual limb as possible.

Screening Evaluation

Even though the patient may not be able to participate fully during an evaluation, the therapist can begin to gather information to guide the early rehabilitation process. Important facts to discern are the patient’s medical status, presence of associated injuries, wound status, ROM, and whether a myodesis (when remnants of major muscles are surgically attached to the bone) or myoplasty (when muscle remnants of the antagonist muscles are sutured to each other) was performed on major antagonist muscle groups during surgery. This basic information helps the therapist develop an intervention plan for early care to facilitate further rehabilitation as the patient’s medical status improves.

Rapport

During the acute care stage, when the patient’s condition is likely to be quite serious, the family suddenly faces many difficult issues and often experiences emotional crisis. Establishing rapport with and providing necessary support to the family are key elements of the acute care stage. Family members may be struggling with questions such as, “How did this happen?” “Why did it happen?” and “What can the future hold?” The family may be overwhelmed by all the medical procedures being performed on their loved one. The therapist should take time to talk with the family, hear their concerns, and explain the goals for the current stage of rehabilitation as well as the long-range prognosis. During this period of crisis, neither the family nor the patient is ready to hear details about all types of prostheses available, but rather may be comforted to know that general prosthetic plans are being made and that the clinical team is working to help achieve a positive outcome that includes a bright future. Rapport with patients can be developed as they become more alert.

Pain Control

During this early phase, pain is primarily controlled by intravenous medication. Strong pain medication may influence the patient’s affect and attitude; the apparent anger and unwillingness to cooperate shown by patients with traumatic amputation may be associated with the pain medication being used. Effective edema control also contributes to pain management. During these first few days, when many professionals are treating the patient day and night, sleep is often interrupted. Coordination of schedules with nursing helps maintain rest periods, which in turn may have a positive effect on pain management.

Wound Healing

Early wound healing and edema control go hand in hand. Wound care protocols may vary depending on physician preference but generally include keeping the wound clean and dry. If a skin graft has been used to close the wound, the limb must be positioned to prevent tension over the suture lines (Figure 31-2). Initial bandage changes may be quite painful for the patient. During the acute period, some physicians prescribe pain medications before bandage changes. Unless contraindicated, a nonadherent dressing such as Xeroform (Kendall, Mansfield, MA) or Adaptic (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) can be used directly over the wound and then covered with sterile bandages. Soaking adherent areas with saline can ease removal of the dressing.

Edema Control

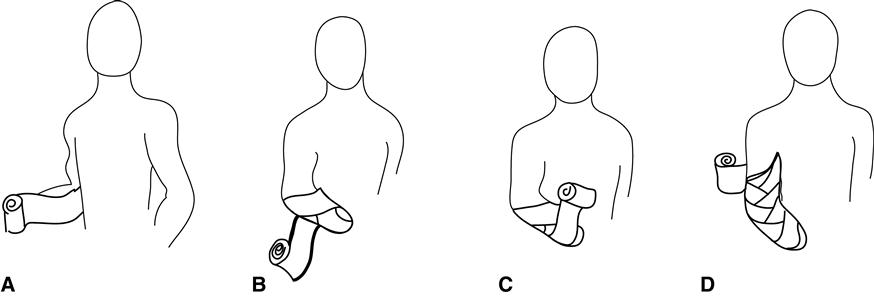

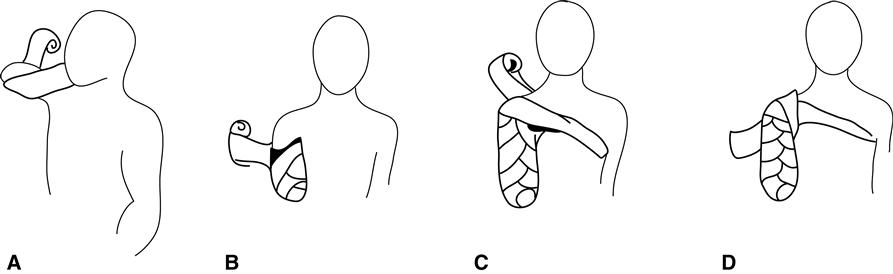

Effective edema control helps reduce the chance of adhesion formation along the healing suture line, aids in wound healing, and management of pain. Edema may initially be controlled by bulky bandages and elevation. When the patient is able to tolerate pressure, elastic bandages may be applied in a figure-of-eight style, with gentle compressive pressure over the distal end that gradually tapers proximally. Ideally, the bandage should continue up and over one joint proximal to the amputation (e.g., above the elbow in transradial amputation) (Figures 31-3 and 31-4). Elastic wraps must be frequently checked for proper placement and compression; close communication with nurses involved in the patient’s care can facilitate this. As wounds heal and are able to tolerate greater compression, elastic wraps are replaced with a “shrinker” or a roll-on liner.

Range of Motion

After injury, patients tend to hold their residual limb in a position of comfort; the arm typically adducted toward the body, the forearm supinated and elbow flexed. Soft-tissue contractures begin to develop if the limb is consistently held in this position. In patients with transhumeral amputation, limitations of shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation are likely to occur. For those with transradial amputation, limitations in elbow extension and pronation are also likely to develop.

Early passive ROM exercise to gently elongate tissues of joints most at risk of contracture formation is essential and can be carefully performed even when intravenous lines are in place. Passive stretching should be performed slowly and gently, just to the point where the therapist begins to feel tension on the muscle or the patient begins to feel pain. Generally, with acute injuries, performing passive ROM twice daily is sufficient to increase motion. If, however, progress is not being made within 2 weeks, the therapist should consider static splinting as an adjunct to passive ROM.

Preprosthetic Rehabilitation

In many facilities, only when wound closure has occurred are patients with new upper-extremity amputation referred for rehabilitation care. During the preprosthetic therapy phase, the patient’s medical condition is often stable enough to begin an active role in care. Education of referral sources about goals of the preprosthetic phase can result in early referrals.

Goals for preprosthetic rehabilitation include the following:

• Establish good rapport and trust with the patient and family.

• Complete a comprehensive evaluation to guide the team in determining an appropriate prosthetic plan.

• Shape and control volume of the residual limb effectively.

• Minimize adhesive scar tissue.

• Desensitize the limb in preparation for prosthetic wear.

• Achieve full ROM in remaining joints of the residual limb.

• Strengthen the muscles of the residual limb to maximize potential for effective prosthetic use.

• Provide appropriate intervention for rehabilitation of associated injuries.

• Help the patient develop some independence in performing basic activities of daily living.

Rapport

In the acute phase of care, when the patient is quite ill, rapport is primarily established with family members. These relationships can help facilitate trust between the therapist and the patient during the early preprosthetic period. Upper-extremity amputation is a major traumatic event that affects the family as well as the patient. As all those involved grapple with the changes and challenges they are facing, the rehabilitation team encourages them to express their hopes, concerns, and fears.

Psychological counseling is considered an integral part of the early rehabilitation program and should be made available for the family and the patient.6 Some patients may benefit from talking to individuals with amputations of a similar level. Speaking with peer counselors can be helpful; however, rehabilitation professions should screen potential peer counselors carefully. Some individuals who sustained amputations in previous years might not have had a good rehabilitation experience or have not had the benefit of more recent prosthetic design and components. A professional should be sure that peer counselors are offering objective and current information.

Comprehensive Evaluation

Before prosthetic options are discussed, a comprehensive examination and evaluation is required. In specialized centers a multidisciplinary team that includes the physical and occupational therapists, a prosthetist, the surgeon or physician, and a psychologist or counselor completes the examination and evaluation. In other facilities the therapists and prosthetists are responsible for completing a comprehensive assessment.

The preprosthetic comprehensive examination begins with a good history and the gathering of preliminary or background data, including the following:

• The cause and date of amputation

• Any associated injuries that might influence the rehabilitation process

The examination continues with an assessment of the psychosocial environment as a resource for rehabilitation and eventual discharge. The therapist assesses the following patient characteristics:

The therapist then considers the condition of the residual limb, documenting the following:

• The presence and description of any phantom limb sensation

• The presence and description of any pain the patient is experiencing

• The length of the residual limb

• The presence of edema, measured by limb circumference

• Skin condition and the presence of scar tissue or soft tissue adhesion

• Evaluation of upper extremity strength

• Evaluation of possible sites for placement of electrodes for myoelectric control

The comprehensive examination concludes with a consideration of mobility and functional status, including the following assessments:

• Posture and skeletal alignment as a result of the missing limb

• Pertinent limitations of the lower extremity

• Postural control (static, anticipatory, and reactionary balance)

If the patient previously used a prosthesis, a prosthetic history also includes the type of prosthesis used, how long the prosthesis was worn each day, and how the prosthesis was used in instrumental and other activities of daily living. The team should determine the patient’s opinions regarding the positive and negative aspects of a previous prosthesis as well as any different or additional functions that the patient wants to achieve.

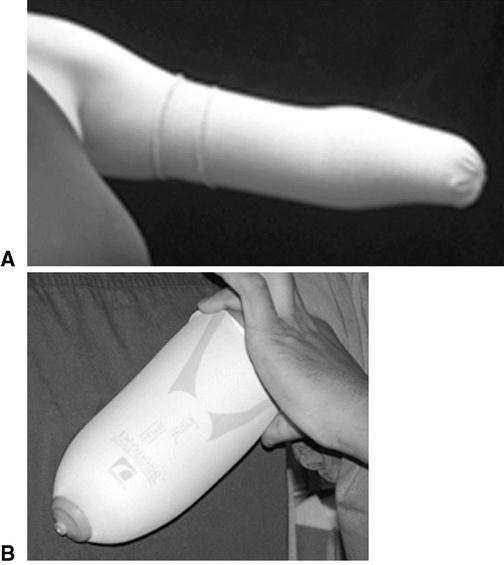

Edema Control and Limb Shaping

As the patient’s medical status improves, bulky bandages are removed and the patient becomes more mobile. The patient must continue to use some type of compression on the limb nearly 24 hours a day, removing it only for wound care and bathing. At this point, elasticized shrinker socks or a roll-on liner may replace the elastic figure-of-eight bandages because they are more convenient and provide more consistent compression (Figure 31-5). For those with transradial residual limbs, the shrinker should extend at least 2 inches above the elbow. For those with transhumeral residual limbs, the sock extends as high as possible on the humerus with a strap going across the chest to anchor it in place.

As limb volume decreases, the shrinker sock should be made smaller (leaving the seam on the outside of the sock) or replaced with a smaller size garment so that it still compresses the residual limb. If shrinker socks are not available or the patient is not yet able to tolerate the compressive force provided by a shrinker, tubular elastic bandaging, such as Compressogrip (Knit-Rite, Kansas City, KS) or Tubigrip (Seton Healthcare Group, Oldham, England), is an alternative. Typically a double layer of bandage is worn, with the layer underneath longer and extending 2 inches further proximally than the second layer.

Edema can further be reduced through soft-tissue mobilization and retrograde massage. Soft-tissue mobilization around areas of adherent tissue through gentle friction massage helps enhance circulation and increase flexibility. Ending treatment with retrograde massage with gentle stroking techniques in the direction of lymphatic flow also helps control edema.7 Heat modalities may be useful as a preparation for subsequent massage and active exercises.

Elevation, while still important, becomes more difficult to enforce with a mobile patient. Raising the residual limb over the head and performing contractions of remaining musculature at least once an hour during the day also helps control edema (Figure 31-6). Active participation in self-care and use of the arm as an assist during functional activities is also helpful.

Management of the Incision and Scar

When the incision lines are adequately closed and sutures have been removed, scar management becomes a primary concern. When adherent scar tissue forms, the tissue of the residual limb does not move freely. Adherent scar tissue near the end of the bone is a particular problem that may lead to skin breakdown because of friction across the scar when the prosthesis is worn. Scar tissue adherence can be minimized by active ROM and gentle friction massage. Circular massage directly over the incision line, with pressure increasing as tolerated, is also a way of minimizing adherent scar formation. A slightly sticky cream or oil, such as pure lanolin or vitamin E oil, is preferred so the scar can be more easily mobilized over underlying tissue. Silicone gel sheeting can be used under bandages to apply pressure directly over the scar to deter adherent scar formation. Kinesio Tex Tape (Bailey Manufacturing, Atlanta, GA) has also been helpful in softening scar tissue.

Desensitization

Persons with recent amputation often have altered sensation or dysesthesias, including incisional pain, phantom sensation, phantom pain, and hypersensitivity. Incisional pain is treated with pain medications and effective edema control. Incisional pain typically subsides as the wound heals and begins to mature and stabilize.

Phantom sensation is a normal phenomenon experienced by most patients with recent amputation. Patients typically report that they “feel” all or part of their amputated limbs. Some describe a pulling, tingling, or burning sensation in the missing limb. Most describe the feeling of a tight fist or a tight band around the arm. Phantom sensation is usually more annoying than painful. Many patients are hesitant to discuss these sensations for fear of sounding “crazy.” For this reason, the likelihood of experiencing phantom sensation should be discussed with the patient as early in the rehabilitation process as possible. As rehabilitation progresses to more motion and prosthetic use, phantom sensation typically decreases to a point at which it is not significantly annoying, but it does not usually disappear entirely.

Phantom pain does not occur in all patients, but when it does it is extremely problematic. Unlike phantom sensation, phantom pain is a pathological condition that may persist long after amputation, hindering functional prosthetic use and lifestyle. A number of treatments have been suggested, including heat, desensitization techniques, imagery, mirror therapy, limb revision, and neurosurgery. Effectiveness of these techniques vary with each patient. Other issues that may be confused with phantom pain include proximal nerve damage and neuromas, which may require limb revision or neurosurgical intervention.8–10

Hypersensitivity is increased sensitivity to stimuli. Light touch is often particularly uncomfortable for the patient with a hypersensitive residual limb. Hypersensitivity can be effectively treated with a systematic and structured program that includes firm massage, various textures stroked on the limb, submersion of the residual limb in various graded media (e.g., dried beans, rice, and popcorn), fluidotherapy, vibration, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and increased functional use of the residual limb during daily activities.11

Enhancing Range of Motion

Having as close to full upper-extremity ROM as possible allows the patient to use the prosthesis to its full capability. Elbow flexion contracture and loss of supination and pronation are common occurrences in patients with transradial amputation. Patients with transhumeral amputation may lose scapula mobility and all shoulder motions, especially external rotation and horizontal adduction. Interventions such as heat modalities, soft-tissue mobilization, gentle stretching, and active ROM exercise can often quickly improve motion in patients with recently developed tissue tightness and ROM restriction. Long-term contractures may require static or static progressive splinting or casting and may take longer to resolve.

The possible loss of lower-extremity ROM caused by immobility and reduced activity during the acute and early rehabilitative phases of care should also be addressed. Limitations in lower-extremity range may affect balance and impede good body mechanics. For those with bilateral upper-extremity amputation, good balance and lower-extremity ROM are essential for the performance of most basic and instrumental activities of daily living.

Strengthening

When the wound has healed and pain is decreasing, strengthening is initiated for all muscles of the residual limb and for major muscle groups of the other extremities. For intact musculature, initial strengthening may be achieved through isometric contraction or active motion. The patient usually quickly progresses to active resistive exercises by using manual resistance, weight cuffs, elastic bands, weight machines, and functional activities.

Management of Concurrent Injuries and Limitations

Traumatic upper-extremity amputations seldom occur in isolation. When an upper extremity is caught in a press or other apparatus, the injured person struggles to get out of the machine by pulling and twisting and even using other extremities to extricate the arm from the machine. The patient can have obvious injuries such as fractures and soft tissue and muscle damage. Other injuries are often present but are not obvious on initial investigation. Painful and limiting rotator cuff injuries of the injured limb or the contralateral shoulder are not uncommon.

Myofascial trigger points are almost always present. Travell and Simons12 describe a myofascial trigger point as a “hyperirritable locus within a taut band of skeletal muscle, located in the muscular tissue and/or its associated fascia. The spot is painful on compression and can evoke characteristic referred pain and autonomic phenomena.” For patients with upper-extremity amputation, trigger points are often found bilaterally in the upper trapezius, rhomboid, and teres minor muscles. Those with transhumeral amputations may have additional trigger point pain in all three portions of the deltoid as well as the biceps, and triceps muscles. Individuals with transradial amputations may have additional trigger point pain in the wrist and finger flexors or extensors. All associated injuries must be treated so the patient can more fully participate in prosthetic training.

Basic Training in Activities of Daily Living

When the dominant hand is amputated, most persons with unilateral amputation choose to change hand dominance for activities requiring fine coordination and manipulative skills, such as writing and eating. Drawing, craft activities, and computer games can all contribute to developing hand coordination and change of hand dominance.

Patients with an upper-extremity amputation are anxious to quickly gain as much independence as possible in basic or survival functional skills such as eating, dressing, and hygiene. Initially adaptive equipment such as modified utensils, button hooks, and writing adaptations may be needed. Assuring the patient that most adaptive equipment will not be needed when they are proficient in prosthetic use helps establish an expectation that the patient will soon be using two “hands.” Remaining bimanual is important for ease of performance and for minimizing risk of overuse syndrome of the remaining extremity.