Fig. 28.1

Demonstration of backswing using driver with bilateral RSPs

Fig. 28.2

Demonstration of follow-through using driver with bilateral RSPs (200-yard drive)

Recommended Protocol

In an effort to standardize a home-based rehabilitation program for most shoulder surgeries, we have developed a program that includes safe, simple exercises that can be easily reproduced in the home environment. These exercises do not require specialized equipment (I provide Theraband to all patients) and can be performed after viewing a Web-based program that can be repeatedly viewed by patients at their leisure and based on their need. Just as with all other protocols, the initial emphasis is on protection of subscapularis repair, slow restoration of passive motion to avoid stiffness, progressive, active-assisted motion, gradual strengthening, and return to activities of daily living. By focusing on patient-oriented, home-based therapy programs, we allow patients to take full responsibility for their recovery and not rely on an outside agency to be responsible for their results.

Previous authors have evaluated muscle activity during shoulder rehabilitation exercises and have noted substantial activity even during simple, light exercises [48]. Although this activity is desired for rehabilitation once the subscapularis or tuberosities have healed, excessive forces are to be avoided, while the healing is taking place. This is as true for the repair of the subscapularis following arthroplasty as well as for tuberosity healing following RSA for fracture. A motivated patient, with the correct guidance, may be the best person to manage their therapy. Pain is a guide for progression of the protocol. Core strengthening and scapular stabilization are two components of shoulder rehabilitation that are often neglected. Failure to address these components may lead to scapular dyskinesis and asymmetry [11, 16, 34]. These components are easily included in the following protocol using simple-to-follow exercises that can be performed at home.

Perhaps the most important visit, either with a therapist or with a physician’s assistant, would be in the preoperative period. Often termed “prehabilitation,” a session or two of instruction to go over the postoperative rehabilitation program is very helpful to the patient. Emphasis is placed on understanding the goals of therapy and practicing their exercises before they experience postoperative pain and immobilization. Immediate postoperative issues such as dressing, bathing, and activities of daily living are addressed so that the patient feels comfortable with those activities prior to surgery. This is very important for elderly patients who live alone and are concerned about their ability to comply with the restrictions following surgery. We routinely schedule a prehabilitation appointment with a therapist, even when patients are planning to do therapy at home postoperatively.

Phase 0 (prehabilitation):

All phases of recovery and rehabilitation are reviewed and practiced with patient.

Activities of daily living are practiced in a sling to simulate recovery.

Phase I (weeks 1 and 2):

Cryotherapy is recommended.

An immobilizer is to be used at all times, except during bathing and exercising;

Core strengthening exercises: alternating single-leg stand against door;

Scapular/deltoid exercises: scapular contractions; deltoid isometric exercises in sling;

ROM exercises: Active ROM (AROM) of the elbow, wrist, and hand;

Supported pendulum exercises (back against wall)

Phase II (weeks 3 and 4):

Cryotherapy is recommended following exercises.

An immobilizer is to be used at all times, except during bathing and exercising;

Core strengthening exercises: alternating single-leg stand—unsupported; lawn mower starts in sling;

Scapular/deltoid exercises: scapular contractions; deltoid isometric exercises in sling;

AROM of the elbow, wrist, and hand;

Initiate table slides1 (Fig. 28.3) and unsupported pendulum exercises.

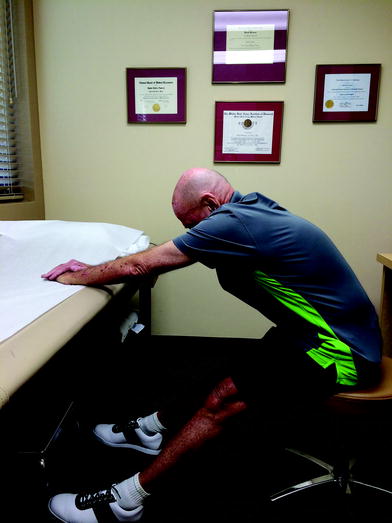

Fig. 28.3

Demonstration of table slide. The patient pushes away from the table on a wheelchair using his legs, while the hands are held fixed on the table

Initiate Active Assisted ROM (AAROM) wand exercises in supine position (Fig. 28.4).

Fig. 28.4

Demonstration of active-assisted wand exercises. Using the unaffected arm to guide, elevation is achieved with gravity assistance

Phase III (weeks 5–8):

The immobilizer is discontinued;

Scapular/deltoid exercises: scapular rows (Fig. 28.5) and deltoid strengthening (Fig. 28.6) with Theraband;

Fig. 28.5

Demonstration of wall slides with lift-off. The lift-off part of the exercise enhances scapular stabilization and allows scapular upward rotation without excessive protraction. This allows almost full elevation which must come from scapular mobility and stability due to the reverse design of the prosthesis

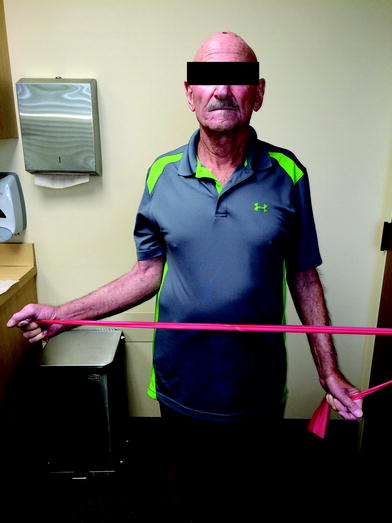

Fig. 28.6

Demonstration of anterior deltoid strengthening with Theraband

Core strengthening exercises: single-leg stand—unsupported; wall sits and squats;

Continue table slides and unsupported pendulum exercises as warm-up.

Continue AAROM wand exercises in supine position. Add standing wand behind back.

Phase IV (weeks 9–12):

Scapular/deltoid/rotator cuff: Theraband exercises to include rows, three-way deltoid, IR, and ER (Fig. 28.7). Increase resistance of bands as tolerated.

Fig. 28.7

Demonstration of external rotation strengthening with Theraband. Proper tension on the teres minor and infraspinatus allows excellent ER and ER strength

Wall push-ups.

Core strengthening exercises: transition to exercise ball—crunches/bridges (as tolerated).

Initiate wall slide program2 (Fig. 28.8). Wall slides only until achieving maximal elevation. Start wall slides with lift-off as tolerated once achieved (Fig. 28.9).

Fig. 28.8

Demonstration of wall slide. I believe that crawling up the wall, as if often taught, encourages scapular upward rotation and protraction, the so-called scapular substitution. Sliding up the wall encourages retraction and stabilization of the scapula

Fig. 28.9

Demonstration of scapular rows with Theraband

Phase V (weeks 13–26):

Scapular/deltoid/rotator cuff: Theraband exercises to include rows, three-way deltoid, IR, and ER. Increase resistance of bands as tolerated;

Wall push-ups;

Core strengthening exercises: transition to exercise ball—crunches/bridges (as tolerated based on conditioning);

Continue wall slide program. Progress as tolerated to wall slides with lift-off, wall slides with eccentric lowering, and wall slides with resisted lowering for eccentric strengthening;

Start sleeper stretches for IR behind back (Fig. 28.10);

Fig. 28.10

Demonstration of sleeper stretch to gain internal rotation

Return to sport as tolerated when indicated by strength, symptoms, and demand of the sport.

Postoperative follow-up with the surgeon is recommended at the end of each phase to assess progress with consideration of transition to formal therapy as each case requires. Referral to formal PT should be considered in patients who are developing greater-than-expected stiffness, pain, or if they demonstrate the inability to follow the home-based program.

A formal PT program is also considered after Phase IV or V if the patient needs assistance to progress to sports-specific activity that requires a higher level of performance. This is a very important role for the therapist to help the patient enhance their recovery following initial recovery from these surgeries. Once the patient’s subscapularis has healed, therapists are extremely effective in evaluating scapular dynamics and can direct therapy to correct any residual dyskinesia. In doing this, the therapist can fine-tune shoulder function and focus on return to desired activities and adjusting for any residual disability following surgery. This is very important for those patients wanting to return to sports. Because the biodynamics of their shoulder has changed, the mechanics of their golf swing, tennis serve, or weightlifting program will change. A physical therapist with a focus on return to sport can be extremely helpful especially for patients retuning to a high level of performance. I have patients who have been able to return to single-digit handicaps in golf and play at the same level as prior to the start of their infirmity.

The results of this review and the TSA study may have significant financial implications. As the burden of healthcare costs continues to rise, reducing or eliminating spending is becoming more important. A typical 1-hour PT visit is estimated to cost $100. Considering that the number of shoulder surgeries is increasing, the cost of PT after all shoulder arthroplasties places a significant financial burden on the healthcare system. Any estimation of cost would also fail to account for the lost time and cost of traveling to the therapy visits, not only for the patients but also for their caregivers who must sacrifice their time to travel with the patient. Increasing, a larger portion of the PT costs are borne by the patient in the form of co-pays in addition to their health insurance premium. Therefore, if PT is not an essential component to the patients’ overall outcome, the overall costs of PT place a significant financial burden on an overextended healthcare system and the patient.

However, we are not advocating the elimination of formal PT. Indeed, we feel strongly that there is an extremely important role for the physical therapist. Formal PT is used in most patients before surgery is considered and often is effective in decreasing pain, restoring function, and obviating the need for surgical intervention. PT is also useful in the patients described above who are having problems with their home exercise program and need further assistance. For these patients, there is an inherent need to have better communication between the therapist and the surgeon to optimize the patient’s result. Additionally, we need better outcome studies’ evaluation not only the effectiveness of treatment, but also its relative value and cost-effectiveness in this changing medical environment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree