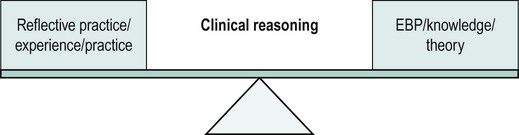

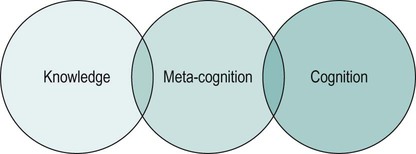

There are numerous definitions of reflection, a selection are provided below. Reflection is a form of mental processing – like a form of thinking – that we use to fulfil a purpose or to achieve some anticipated outcome. It is applied to relatively complicated or unstructured ideas for which there is not an obvious solution and is largely based on the further processing of knowledge, understanding and possibly emotions that we already possess (Moon 1999). It is clear from the numerous definitions of reflection that people develop personal and individual views of what reflection is; this is influenced by factors such as disciplinary background. The differences in terms used, interpretation and perspective can result in confusion; however, there are clear commonalities and overlap within the work of different authors on the subject. In its simplest form, reflective practice is a process of thinking about and analysing an experience or set of actions. In this case, it would relate to a work scenario or situation. There are many tools that can help processes of reflection, such as keeping reflective logs or diaries, which will be discussed later in the chapter; this is common practice with many other disciplines, such as nursing and sports coaching (Knowles and Telfer 2009). Knowles and Telfer (2009: 24) make it clear that reflective practice is not just a process of thinking where you literally ‘go round in circles’, but a cognitive process which encompasses ‘deliberate exploration of thoughts, feelings and evaluations focused on practitioner skills and outcomes. The outcome of reflection is not always preparation for change, or action based, but perhaps confirmation/rejection of a theory or practice skill option’. This description gives the process of reflection a feeling of trajectory where the individual undertaking the reflection ends up in a different place from where they started, whether through new understanding of practice, new knowledge or both. This process of moving forward is crucial in gaining a better understanding of effective practice. Understanding what is not working well in a service, process or any practice situation is just as important as identifying positive practice – it highlights what needs to change. For further reading on the topic of reflection and reflective practice see Ghaye (2005), Moon (1999) and Schon (1983). As well as developing individual skills and expertise, it is vital that physiotherapists understand how best to work together in interprofessional teams (Zwarenstein and Reeves 2006). Therefore, reflection should not be just about self and the work context but the wider scope of team activities. Interprofessional working requires an understanding of the boundaries or limits within which any professional both could and should operate (Dugdill et al. 2009). Reflective practice plays a vital part in enabling professionals to learn and understand the impact of their actions. External factors, such as workplace policy and professional body requirements, as well as internal factors, such as attitudes, skills, experience and team dynamics, can all be issues that are useful to report on. As it can be seen it is therefore obviously not something that can come from absorbing. As Higgs and Jones (2008) state, clinical reasoning relies on the integration of three key processes in order to be successful (Figure 5.1). Knowledge: this relates to an individual’s personal knowledge of anatomy and physiology, and knowledge of pathological and inflammatory processes. It also includes knowledge of evidence and how to evaluate it appropriately. It should also encompass valuing and considering the patient’s knowledge of their health. Cognition: this relates to an individual practitioner’s ability to analyse data, synthesise information and develop strategies of inquiry. In other words, their ability to think through the information you collect and problem solve. Meta-cognition: this relates to an individual practitioner’s ability to review the strategies they are using, consider what might have influenced/biased/limited them, compare this experience against previous ones and generally be critically analytical of their practice. Novice practitioners tend to use what is often known as hypothetico-deductive clinical reasoning (Jones et al. 2008). This is where hypotheses (initial impressions) are systematically tested out in order to reach a logical, diagnostic conclusion. This requires a significant cognitive demand, tends to focus primarily on physical impairments and may still result in the actual reason for presentation being elusive. By contrast, an expert is said to be someone who is perceived to be ‘capable of doing the right thing at the right time’ (Jensen et al. 2008: 123) – their method of clinical reasoning will be different in that it is based on pattern recognition (colloquially termed ‘patient mileage’) with not only large numbers of possible hypotheses considered but various other components of the individual patient and context taken into account. These include the patient motivations, reasoning based on the rapport and collaboration with the patient, envisioning the future and considering ethical implications (Jones et al. 2008). While seemingly more complex, this process actually requires less cognitive demand at the time of assessment. There can be a perceived tension between the drive toward developing the scientifically researched evidence base for physiotherapy practice and the value of professional knowledge developed through experience. Much has been written previously on the processes of reflective practice as being part of a continual learning cycle (Ghaye 2005). Students are taught from an evidence base of ‘what works’, but the literature is often not complete or not relevant for the working context, so experiential learning ‘from practice’ and evaluation of that practice is required in order to understand what processes and interventions work best in order to develop clinical reasoning skills. Additionally, as a clinician you need to be critical of current practice and may be working in a brand new or extended role (Figure 5.2). In this case, gaps in the literature base and/or your own experiences of implementing current practice may generate further questions for ongoing research. As Dugdill (2009:49) previously stated: Therefore, reflective practice should be seen as a central process for both continuing professional development (CPD) and evidence-based approaches, both of which are fundamental to high quality professional practice. Without all these described processes being in play you will not be able to achieve your full potential as a physiotherapist remembering that ‘clinical reasoning and clinical practice expertise is a journey, an aspiration and a commitment to achieving the best practice that one can provide’ (Higgs and Jones 2008: 9). For further reading on these topics please refer to Higgs et al. (2008). In order to practice as a physiotherapist within the UK, practitioners must hold registration with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC). HCPC standards ensure that all health professionals must continue to develop their knowledge and skills in order to maintain registration. These standards (HCPC 2006) state that registrants must: 1. maintain a continuous, up-to-date and accurate record of their CPD activities; 2. demonstrate that their CPD activities are a mixture of learning activities relevant to current or future practice; 3. seek to ensure that their CPD has contributed to the quality of their practice and service delivery; 4. seek to ensure that their CPD benefits the service user; 5. present a written profile containing evidence of their CPD upon request. The HCPC states that physiotherapists must participate in ‘a wide range of learning activities through which health professionals maintain and develop throughout their career to ensure that they retain their capacity to practise safely, effectively and legally within their evolving scope of practice’ (AHP Project 2003: 9). The use of reflection is identified as one of the key activities, especially in learning from practice in the workplace. The recognition of learning requires a process of reflection and evaluation and it is this process that can prove difficult. Yet, reflecting on workplace practice after it has occurred is integral to workplace learning. It enables subconscious thought to be critically examined, evaluated and articulated. It also allows theories from formal programmes of study to be connected with and integrated into practice. Undergraduate and postgraduate physiotherapy programmes commonly use reflection as a component of assessment; this can be formal, summative assessment or more informal, formative assessment. Because the work is being produced for an external reader who will make a judgement about the ‘quality’ of that reflection and often give it a mark, the nature and content of the reflection will, inevitably, be altered. There is much debate within the literature regarding the effects of assessment on the development of honest and truthful reflection. A student, knowing the reflective essay or portfolio is to be assessed, will frame the written response to make them (and their practice/expertise) appear in a positive light; hence, the ‘messy reality’ and mistakes of practice may be lost from the reflective account. Some argue that reflection and assessment are incompatible (Hargreaves 2004); however, many practitioners will admit that without the external motivation that assessment provides, combined with the formal training and feedback received through the process, they would not have devoted the time and energy to developing the skill. Even the use of ‘I’ within academic writing can be seen as controversial in academic settings; traditional academic assignments require writing in the third person and discourage the expression of personal or unsubstantiated comment (Lindsay et al. 2010). The following quotes from physiotherapy students and graduates highlight the debate and motivations for undertaking assessed reflection: Some literature suggests that the descriptive nature of a reflection can be the result of its involvement in an assessment process because the reflector holds back on emotions, opinions and is less open and honest as someone will be reading it (Hargreaves 2004). Personally I do not believe this applies to me…

Reflection

Defining reflection

Rationale for reflection in practice

Clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice

Applying the above concepts to a real world physiotherapy context, for example the painful shoulder

Requirements for reflective practice

Use of reflection as A form of assessment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine