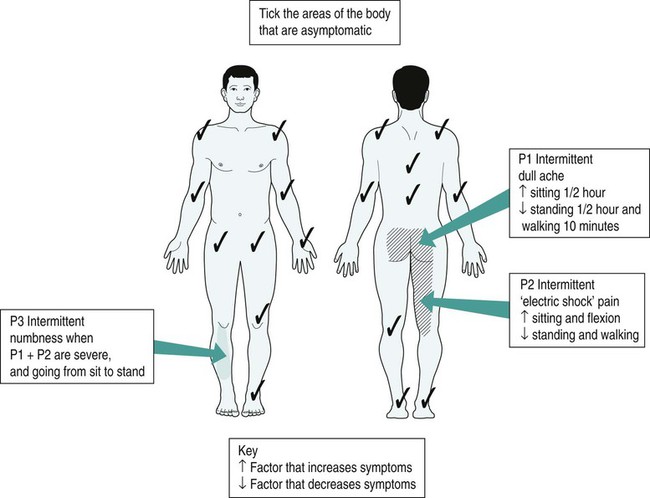

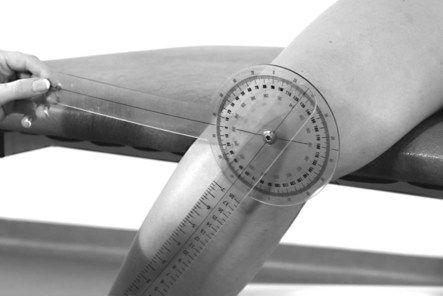

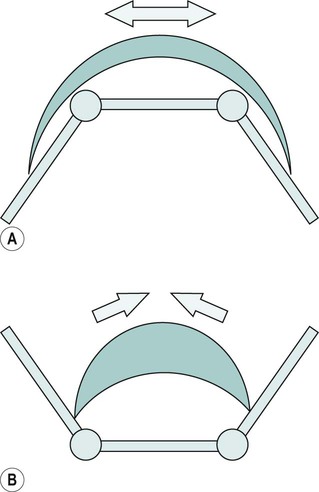

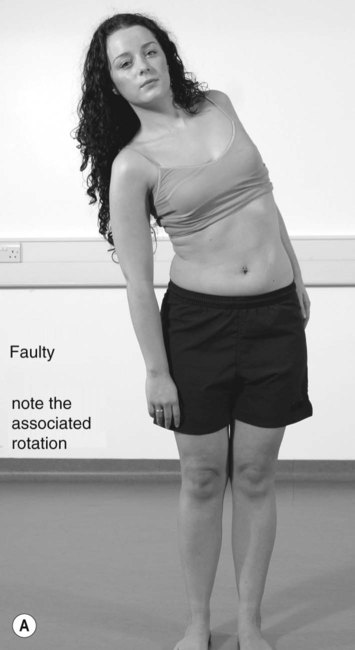

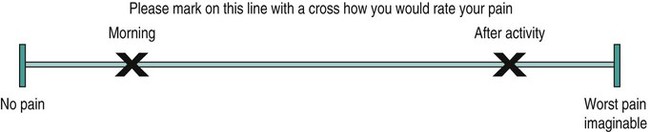

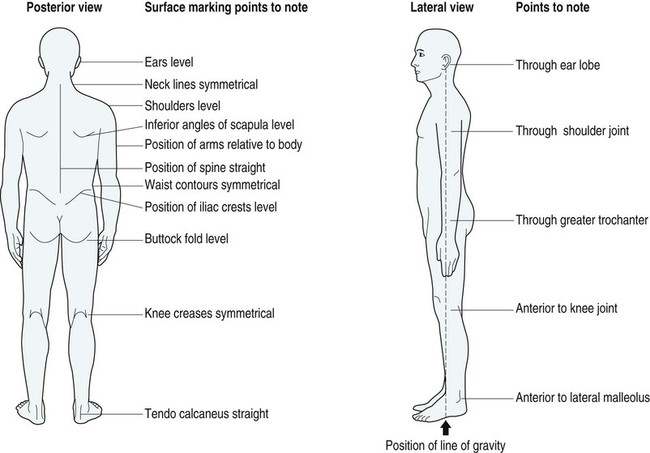

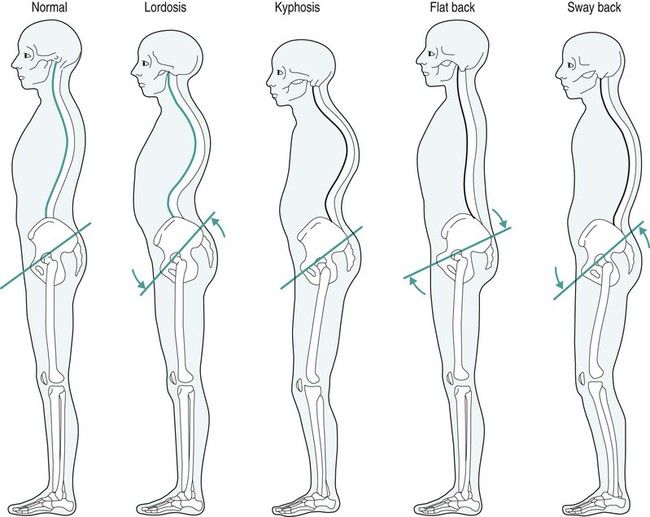

• to identify the appropriate questions to include in a subjective musculoskeletal assessment; • to discuss the use of regional and special questions for particular joints; • to explain the use of appropriate subjective and objective markers; • to explain the use of specific and regional tests at particular joints; Recent years have seen the introduction of extended-scope practitioners, clinical specialist and consultant physiotherapy posts. Physiotherapists in these roles are assessing patients usually referred by general practitioners (GPs) who would otherwise have been examined by a consultant orthopaedic surgeon. These practitioners are required to possess excellent assessment skills, a wide experience of different clinical conditions and pathologies, and to be able to recognise the appropriate course of action for that particular patient. Audits of these interventions have been encouraging; Gardiner and Turner (2002) found that the extended-scope practitioners showed more consistency between clinical diagnosis and arthroscopic findings in the knee than did their medical counterparts. In the present climate, these posts, along with the newly established consultant physiotherapist role, are likely to expand and in doing so will deservedly raise the profile of the physiotherapy profession. • On first patient contact, it is essential to perform an initial assessment to determine the patient’s problems and to establish a treatment plan. • During the treatment, assessment is particularly appropriate while performing treatments such as mobilisations and exercises when the patient’s signs and symptoms may vary quite rapidly. Be aware of any improvement or deterioration in the patient’s condition as and when it occurs. • Following each treatment, the patient should be reassessed using subjective and objective markers in order to judge the efficacy of the physiotherapy intervention. Assessment is the keystone of effective treatment without which successes and failures lose all of their value as learning experiences. Subjective and objective markers are explained later in this chapter. • At the beginning of each new treatment, assessment should determine the lasting effects of treatment or the effects that other activities may have had on the patient’s signs and symptoms. In reassessing the effect of a treatment, it is essential to evaluate progress from the perspective of the patient, as well as from the physical findings. Objective examination is concerned with performing and recording objective signs. It aims to: • reproduce all or parts of the patient’s symptoms; • determine the pattern, quality, range, resistance and pain response for each movement; • identify factors that have predisposed or arisen from the disorder; • obtain signs on which to reassess the effectiveness of treatment by producing reassessment ‘asterisks’ or ‘markers’ (Jull, 1994). It is also essential for the physiotherapist to obtain sufficient details of the patient’s employment. Is the patient currently working? If not, determine the reasons for this. Is it because the person is unable to cope with the physical demands of the job? Do heavy lifting, repetitive movements or inappropriate sustained postures increase the symptoms? These factors may be precursors of poor posture and muscle imbalance, which may accentuate degenerative disease and increase symptoms. However, it is equally important to recognise that withdrawing from normal activities of daily life can result in deconditioning of musculoskeletal structures that may lead to degenerative disease and an increase in symptoms (Waddell 1992; Frost et al. 1998). It is useful to record the area of the pain by using a body chart, because this affords a quick visual reference (Maitland 2001). The patient may complain of more than one symptom, so the symptoms may be recorded or referred to individually as P1 and P2 and so on. Areas of anaesthesia or paraesthesia may be recorded differently on the pain chart – they may be represented as areas of dots in order to distinguish them from areas of pain (Figure 11.1). The severity of the pain may be measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS) (Figure 11.2) or on a numerical scale of 0–10 to quantify the pain, where 0 stands for no pain at all and 10 is perceived by the patient as the worst pain imaginable. The mark on a VAS can then be measured and recorded for future comparisons using a ruler. Although these measures are not wholly objective, they do allow changes to be monitored as the treatment progresses. Most musculoskeletal pain is mechanical in origin and is therefore made better or worse by adopting particular positions or postures that either stretch or compress the structure that is giving rise to the pain. Moreover, aggravating and easing movements may provide the physiotherapist with a clue as to the structure that is causing the pain. Various body or limb positions place different structures on stretch or compression and the resultant deformation produces an increase in severity of the pain. The aggravating and easing factors can be recorded on the pain chart, as in Figure 11.1. It is also necessary to record the length of time that engaging in aggravating activities produces an increase in symptoms or, alternatively, takes to settle down. This indicates the irritability of the patient’s condition. Be careful not to confuse time of day with the performance of particular activities that the patient may undertake at that time. Certain pathologies tend to be more painful at characteristic times of the day. For example, chronic osteoarthritic changes are characteristically painful and stiff initially on arising from sleep, intervertebral disc related pain is often more painful on arising owing to the disc imbibing water during sleep and thus exerting pressure on pain-sensitive structures. Prolonged morning pain and stiffness, which improves only minimally with movement, suggests an inflammatory process (Magee 1992). Scans are now commonly used to aid the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders. X-rays are useful in that they show the degree or extent of arthritis present at a joint. They are also useful in determining the extent of osteomyelitis (bone infection) and some malignancies and osteoporosis. Moreover, they are valuable following trauma to identify fractures or dislocations. Be aware, however, that there is a poor correlation between X-rays and spinal symptoms for non-specific low back and neck pain. What is identified as pathological on these tests may not always be the structure responsible for the patient’s signs and symptoms. Routine X-rays are not helpful in non-specific degenerative spinal disease (CSAG 1994). • Physiological movements are movements that could be performed actively by the patient (e.g. flexion of the knee or abduction of the shoulder joint). • Accessory movements cannot be performed actively by the patient (e.g. they incorporate glide, roll or spin movements that occur in combination as part of normal physiological movements). An example of an accessory movement is an anterior–posterior glide at the knee joint. Active movement may be assessed by the use of a goniometer (Figure 11.3) or, alternatively, by visual estimation. It is measured in degrees and it is useful to practise using the goniometer by measuring the hip, knee and ankle joints in various positions. Either the 360° or 180° universal goniometers may be used. Ensure adequate stabilisation of adjacent joints prior to taking the measurements and locate the appropriate anatomical landmarks as accurately as possible. For details on specific joint measurements using the goniometer, refer to the appropriate joint assessment. Physiological and accessory passive movements are measured in terms of the above and by the end-feel respectively. If a lesion is situated within a non-contractile structure such as ligament, then both the active and passive movements will be painful and/or restricted in the same direction. For example, both the active and passive movement of inversion will produce pain in the case of a sprained lateral ankle ligament. However, if a lesion is within a contractile tissue such as a muscle, then the active and passive movements will be painful and/or restricted in opposite directions (Cyriax 1982). For example, a ruptured quadriceps muscle will be painful on passive knee flexion (stretch) and resisted knee extension (contraction). During passive movements, the end-feel is noted. Different joints and different pathologies have different end-feels. The quality of the resistance felt at the end of range has been categorised by Cyriax (1982). For example: • bony block to movement or a hard feel is characteristic of arthritic joints; • an empty feel, or no resistance offered at the end of range, may be a result of severe pain associated with infection, active inflammation or a tumour; • a springy block is characterised by a rebound feel at the end of range and is associated with a torn meniscus blocking knee extension; • spasm is experienced as a sudden, relatively hard feel associated with muscle guarding; Objective measurements of strength throughout different joint angles and at different velocities are made more accurately using isokinetic machines, such as Cybex or Kin-Kom. These machines are particularly valuable in rehabilitative regimens such as anterior cruciate rehabilitation programmes and can determine the strength ratio of the quadriceps to the hamstrings, or the ratios of the operated versus the non-operated leg. Objective markers such as percentages of strength ratios or ratios of operated versus non-operated leg may be used in setting discharge protocols. Isokinetic machines have been found to be reliable and valid in measuring muscle torque, muscle velocity and the angular position of joints (Mayhew et al. 1994). However, they are limited in their use, and Wojtys et al. (1996) suggest that agility and functional exercises may be more beneficial than isokinetic machines in the strengthening of muscle. This occurs with muscles that act over two joints (Figure 11.4a). The muscle cannot stretch maximally across both joints at the same time. For example, the hamstrings may limit the flexion of the hip when the knee joint is in extension as they are maximally stretched in this position. However, if the knee is flexed passively, then the hip will be able to flex further as the stretch on the hamstrings has been reduced. This, too, occurs with muscles that act over two joints (Figure 11.4b). The muscle cannot contract maximally across both joints at the same time. An example is the finger flexors. If you are to make a strong fist, you may notice that the wrist is in a neutral or an extended position when you do this action. Now, if you attempt to actively flex your wrist joint whilst keeping your fingers flexed, you will find that the strength of the grip is greatly diminished. This is because the wrist and finger flexors are unable to shorten any further and so the fingers begin to extend or lose grip strength. Signs and symptoms may include: • pain that increases on weight-bearing activities (standing and walking, walking downstairs particularly); • insidious onset of symptoms followed by progressive periods of relapses and remissions; • pain and stiffness in the morning; • stiffness following periods of inactivity; • pain and stiffness that arise after unaccustomed periods of activity; • bony deformity (e.g. characteristic varus deformity may follow from collapse of the medial compartmental joint space); • reduction of the joint space observed on X-ray, with bony outgrowths or osteophytes. Posteriorly, the shoulders, waist creases, posterior superior iliac spines, gluteal creases and knee creases should be horizontal (Figure 11.5). The spine should appear to be vertical. There should be no rotation, side flexion, scoliosis (lateral curvature) or shift (lateral deviation). Laterally, you should observe a normal lordosis in the lumbar spine. Anteriorly, the anterior superior iliac spines should be horizontal. • Creases in the posterior aspect of the trunk and, particularly, adjacent to the spine may indicate areas of hypermobility or instability of that motion segment. • Sway back comprises hyperextension of the hips, an anterior pelvic tilt and anterior displacement of the pelvis. • Flat back consists of a posterior pelvic tilt and a flattening of the lumbar lordosis, extension of the hip joints, flexion of the upper thoracic spine and straightening of the lower thoracic spine. • Kypholordosis consists of a forward-poking chin posture, elevation and protraction of the shoulders, rotation and abduction of the scapulae, an increased thoracic kyphosis, anterior rotation of the pelvis and an increased lumbar lordosis. • Shifted posture (lateral shift) commonly arises from disc herniation or acute irritation of a facet joint. The shift is thought to result from the body finding a position of ease whereby the shoulders are displaced laterally in relation to the pelvis. Most commonly the shift occurs away from the painful side (Figure 11.7). Flexion should result in a smooth curve. Segmental areas of give or restriction appear as hinging (segmental hypermobility). Lack of movement in the lumbar spine may be compensated by flexion at the hips or thoracic spine flexion. The gross movement may be measured as fingertip-to-floor distance with a tape measure. Note any limitation of movement, lateral deviation and pain response (Figure 11.8). Repeating movements several times may alter the quality and range of the movement and may give rise to latent pain. McKenzie (1981) advocates the use of repeating flexion and extension in both standing and lying to determine the movement that may centralise the patient’s symptoms (Figure 11.10). According to Palmer and Epler (1998), progressive worsening of pain on repeated movements indicates a disc derangement – the pain either becoming more intense or spreading more distally. Centralisation of symptoms means that the referred pain becomes more proximal, i.e. pain experienced at the medial aspect of the shin may centralise to the buttock. Thus, the exercise is believed to be reducing the patient’s symptoms and the disc derangement. These test the integrity of the posterior sacroiliac ligaments. The patient lies supine and the hip is passively flexed towards the ipsilateral shoulder (Figure 11.11). A downward thrust is applied along the line of the femur. Observe for pain response, clunk and difference in end-feel between both sides. The test is repeated for (oblique) hip flexion towards the contralateral shoulder and (transverse) hip flexion towards the contralateral hip. Flexion plus abduction plus external rotation (the ‘Faber’ test) tests the integrity of the anterior sacroiliac ligaments. The test is also described as the ‘four test’ because of the position of the patient’s limb, a combination of flexion, abduction and external rotation. The physiotherapist pushes the leg downward, just proximal to the knee joint while stabilising the opposite hip with the other hand. A normal finding would be to lower the leg to the level of the opposite leg. Observe for pain response or limitation of movement (Figure 11.12). A myotome is a muscle supplied by a particular nerve root level. These are assessed by performing isometric resisted tests of the myotomes L1–S1 in middle range, held for approximately three seconds. Test the unaffected side, then the affected: LI–L2 for the hip flexors (see Figure 11.13), L3–L4 for knee extensors (see Figure 11.14), L4 for foot dorsiflexors and invertors, L5 for extension of the big toe, S1 for plantar flexion (see Figure 11.15) and knee flexion, S2 for knee flexion and toe standing, and S3–S4 for muscles of the pelvic floor and the bladder. • Test the non-affected first then affected side. Note: dull reflexes may indicate lower motor neurone dysfunction. Brisk reflexes may indicate an upper motor neurone dysfunction. • L3 corresponds to the quadriceps. The patient sits with the knee flexed and the therapist hits the patellar tendon just below the patella (Figure 11.16). • S1 corresponds to the plantarflexors. Dorsiflex the ankle and strike the Achilles tendon. Observe and feel for plantar flexion at the ankle (Figure 11.17). This is also known as Lasegue’s test. The patient is supine. The physiotherapist lifts the patient’s leg while maintaining extension of the knee (Figure 11.18). An abnormal finding is back pain or sciatic pain. The sciatic nerve is on full stretch at approximately 70 degrees of flexion, so a positive sign of sciatic nerve involvement occurs before this point (Palmer and Epler 1998). Any pain response and range of movement is noted and comparison made with the other side. Factors such as hip adduction and medial rotation further sensitise the sciatic nerve; dorsiflexion of the ankle will sensitise the tibial portion of the sciatic nerve; plantar flexion and inversion will sensitise the peroneal portion of the nerve. The patient lies prone and the physiotherapist flexes the person’s knee and then extends the hip (Figure 11.19). Pain in the back or distribution of the femoral nerve indicates femoral nerve irritation or reduced mobility. Comparison is made with the other side. This tests the mobility of the dura mater. The patient sits with thighs fully supported with hands clasped behind the back. The patient is instructed to slump the shoulders towards the groin (Figure 11.20). The physiotherapist applies gentle overpressure to this trunk flexion. The patient adds cervical flexion, which is maintained by the therapist. The patient then performs unilateral active knee extension and active ankle dorsiflexion. The physiotherapist should not force the movement. The non-affected side should be assessed first. Stability of the lumbar spine is necessary to protect the lumbopelvic region from the everyday demands of posture and load changes (Panjabi 1992). It is essential for pain-free normal activity (Jull et al. 1993) and should always be assessed. With the patient in crook lying with the hips at 45 degrees flexion, he/she is instructed to maintain a neutral spine (it may be useful to tell the patient to maintain such a lordosis that an army of ants could just crawl through!). The person then performs an abdominal in-drawing by contracting the transversus abdominis muscle while attempting to maintain the spine in neutral. To challenge the transversus abdominis and multifidus stabilising muscles (and consequently the spinal position), the patient adds the leg load by alternately lifting the heels from the floor and sliding out the leg while maintaining a neutral spine position. The maintenance of a neutral spine posture can be assessed by using a biofeedback device. An inability to maintain the spine in neutral will result in the lumbar spine extending as the leg is lifted. The intra-abdominal pressure mechanism is controlled primarily by the diaphragm and transversus abdominis which provides a stiffening effect on the lumbar spine (Hodges and Richardson 1997). Soft-tissue thickening over the articular pillar at one or more spinal levels is a common finding in cases of degenerative disease of the lumbar spine, as is hard bony thickening and prominence over the apophyseal joints. Note any general tightness or localised thickening of muscular tissue or ligamentous tissue. In general, the older the soft-tissue changes, the tougher they are; the more recent, the softer they are. However, a thickened or stiff area is not necessarily painful or the source of a patient’s symptoms (Maitland 2001). The physiotherapist applies central posteroanterior pressures on the spinous processes and unilateral (one-sided) pressure over the articular pillar (Figure 11.21), noting areas of hyper- and hypomobility. Record any pain experienced by the patient and the corresponding spinal level.

Musculoskeletal assessment

Introduction

General issues

When should physiotherapists assess patients?

Aims of the objective assessment

Subjective assessment

Initial questioning

Present condition

Area of the symptoms

Severity of the symptoms

Aggravating and easing factors

Positional factors

Time factors

Investigations

X-rays, MRI scans, CAT scans and bone scans

Objective assessment

Assessment of movement

Passive movements

Assessment of range of movement

Measurement of joint range using a goniometer

Differentiation tests

End-feel

Assessment of muscle strength

Measurements using isokinetic machines

Differentiation tests of muscles and tendons

Passive insufficiency of muscles

Active insufficiency of muscles

Characteristics of degenerative joint disease

Spinal assessments

The lumbar spine

Posture

Normal alignment

Common deviations from normal posture (refer to Figure 11.6)

Movements

Active movements

Flexion

Repeated movements

Compression tests

Posterior ligaments

Anterior ligaments – Faber test

Neurological testing

Myotomes

Reflexes

Adverse mechanical tension

Straight leg raise (SLR)

Prone knee bend (femoral nerve stretch)

Slump test

Testing for lumbopelvic stability

Palpation

Accessory spinal movements

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree