Radio-Scapho-Lunate Arthrodesis with Distal Scaphoid Excision

Marc Garcia-Elias

Introduction

Painful dysfunction of the radioscapholunate (RSL) joint can occur secondary to a number of post-traumatic, inflammatory, and noninflammatory conditions. When symptomatic, this problem may necessitate fusing the RSL joint (1,2,3,4,5,6,7). Once solidly fixed to the radius, however, the scaphoid starts to behave like a lateral malleolus; it obstructs radial inclination and flexion of the midcarpal joint (3). Indeed, after this type of arthrodesis, the ball-and-socket scapholunocapitate joint becomes tightly constrained laterally by the unyielding scaphoid. With time, the resulting increased stress at the scaphoidtrapeziumtrapezoid (STT) interval may induce painful dysfunction of that joint. According to Nagy and Büchler (3), the long-term results following RSL arthrodesis are characterized by an “unacceptable high complication rate.” In their series of 15 RSL fusions, 8 required reoperations for secondary midcarpal joint degeneration, scaphoid fracturing, or nonunion of the arthrodesis, most of these problems being the consequence of an abnormally elevated stress in the STT joint.

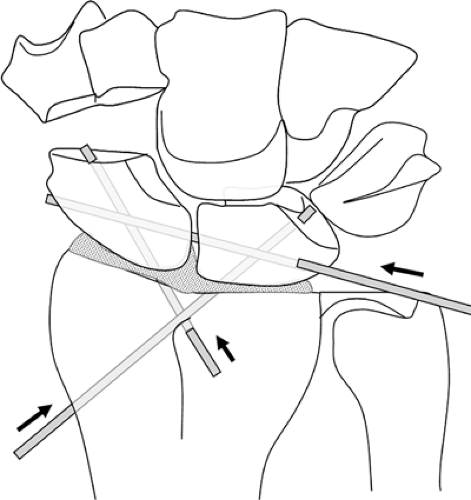

To address these issues and thereby minimize the morbidity associated with RSL fusions, an additional surgical step has been proposed, namely excision of the distal scaphoid (8,9,10,11). In a series of cadaver investigations, McCombe et al. (8) simulated a radioscaphoid arthrodesis with transfixing Kirchner wires (K-wires). The reduction in wrist motion was shown to be substantially less if the distal portion of the scaphoid was concomitantly removed. Garcia-Elias et al. (9,10,11) have recently published further clinical data confirming these in vitro experimental findings. This supplementary maneuver hence represents a sound approach to allow better range of motion for the scapholunocapitate “ball-and-socket” joint with the risk largely reduced of developing secondary midcarpal degeneration. What follows is a review of the indications, surgical technique, and results of this procedure (Fig. 24-1).

Indications

Radioscapholunate fusion plus distal scaphoid excision is indicated if the midcarpal joint is normal and the radiocarpal articulation is seriously damaged as a result of one or several of the following conditions:

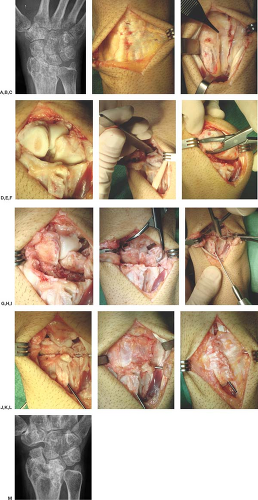

Isolated idiopathic radiocarpal degenerative joint disease (Fig. 24-2)

Traumatic, septic, rheumatoid, or iatrogenic radiocarpal chondrolysis (Fig. 24-3)

Noncorrectable intra-articular fracture malunion of the distal radius

Irreducible acute multifragmentary intra-articular fracture of the distal radius

Radioscaphoid degeneration secondary to chronic scapholunate dissociation (scapholunate advanced collapse [SLAC] grade II)

RSL joint degeneration secondary to chronic lunotriquetral dissociation

Ulnar translocation instability with cartilage wear of both scaphoid and lunate fossae

Radiocarpal instability after vascularized fibular grafting of a resected tumor of the distal radius

Contraindications

RSL arthrodesis is not indicated

If the midcarpal joint is not congruent or with poor cartilage

If the midcarpal joint is affected by the progressive disease that ruined the radiocarpal joint, this progression being inevitable

If there is florid local osteomyelitis or septic arthritis

Preoperative Preparation

Before surgery, aside from the usual clinical examination and routine radiographic assessment of the wrist, it is useful to perform the following:

Fluoroscopic evaluation of midcarpal joint (anterior and posterior drawer tests) to check integrity of the midcarpal stabilizing ligaments

Ulnar deviated stress view to rule out the existence of a lunohamate impingement in cases of lunate type II (12).

Arthroscan, magnetic resonance imaging with dedicated surface coils, or diagnostic arthroscopy to assess the status of cartilage of the two opposing surfaces of the midcarpal joint (13).

Technique

The patient is in a supine position, shoulder abducted, arm in full internal rotation, elbow extended and forearm lying on the hand surgery table.

Regional anesthesia: interscalene or axillary brachial plexus block is preferred over general anesthesia.

Exsanguinate the arm and control it with a tourniquet.

Perform a 6-cm long, longitudinal or S-shaped dorsal approach centered on Lister’s tubercle. Identify and protect the dorsal branches of the radial and ulnar nerves (Fig. 24-2B)

Divide the extensor retinaculum along the compartment 3, releasing completely the extensor pollicis longus.

Release all septae between compartments 2, 3, 4, and 5 extensor compartments and coagulate intraseptal vessels. It is particularly important to control the fourth compartment artery, located within the 4-5 septum.

Figure 24-2 This 38-year-old man had a grossly displaced intra-articular distal radial fracture that was initially treated with external fixation and percutaneous Kirschner wire (K-wire) fixation. Subsequently he developed complex regional pain syndrome type I that resulted in painful radiocarpal stiffness. A:Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree