Radial Head

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Radial head fractures account for 1.7% to 5.4% of all fractures, and one-third of all elbow fractures.

One-third of patients have associated injuries such as fracture or ligamentous damage of the shoulder, humerus, forearm, wrist, or hand.

ANATOMY

The capitellum and the radial head are reciprocally curved.

Force transmission across the radiocapitellar articulation takes place at all angles of elbow flexion and is greatest in full extension.

Full rotation of the head of the radius requires accurate anatomic positioning in the lesser sigmoid notch.

The radial head plays a role in valgus stability of the elbow, but the degree of conferred stability remains disputed.

The radial head is a secondary restraint to valgus forces and seems to function by shifting the center of varus-valgus rotation laterally, so the moment arm and forces on the medial ligaments are smaller.

Clinically, the radial head is most important when there is injury to both the ligamentous and muscle-tendon units about the elbow.

The radial head acts in concert with the interosseous ligament of the forearm to provide longitudinal stability.

Proximal migration of the radius can occur after radial head excision if the interosseous ligament is disrupted.

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Most injuries result from a fall onto the outstretched hand, the higher energy injuries representing falls from a height or during sports.

The radial head fractures when it impacts the capitellum. This may occur with a pure axial load, with a posterolateral rotatory force, or as

the radial head dislocates posteriorly as part of a posterior Monteggia fracture or posterior olecranon fracture-dislocation.

Axial load at 0 to 35 degrees elbow flexion results in a coronoid fracture.

Axial load at 0 to 80 degrees elbow flexion results in a radial head fracture.

It is frequently associated with injury to the ligamentous structures of the elbow.

It is less commonly associated with fracture of the capitellum.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Patients typically present with limited elbow and forearm motion and pain on passive rotation of the forearm.

Well-localized tenderness overlying the radial head may be present, as well as an elbow effusion.

The ipsilateral distal forearm and wrist should be examined. Tenderness to palpation or stress at the distal radioulnar joint may indicate the presence of an Essex-Lopresti lesion (radial head fracturedislocation with associated interosseous ligament and distal radioulnar joint disruption).

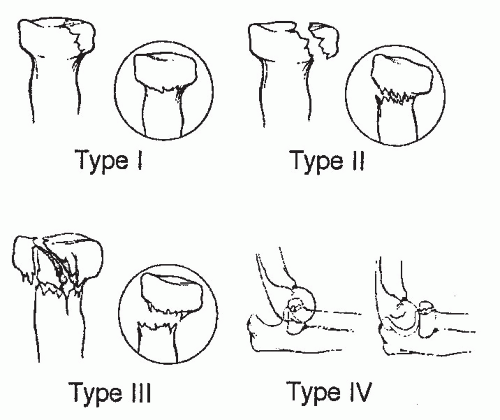

Medial collateral ligament competence should be tested, especially with type IV radial head fractures in which valgus instability may result. This may be difficult in the acute setting.

Aspiration of the hemarthrosis through a direct lateral approach with injection of lidocaine will decrease acute pain and allow evaluation of passive range of motion. This can help identify a mechanical block to motion.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

Standard anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the elbow should be obtained, with oblique views (Greenspan view) for further fracture definition or in cases in which fracture is suspected but not apparent on AP and lateral views.

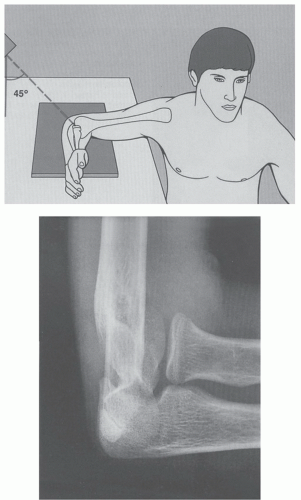

A Greenspan view is taken with the forearm in neutral rotation and the radiographic beam angled 45 degrees cephalad; this view provides visualization of the radiocapitellar articulation (Fig. 20.1).

Nondisplaced fractures may not be readily appreciable, but they may be suggested by a positive fat pad sign (posterior more sensitive than anterior) on the lateral radiograph, especially if clinically suspected.

Complaints of forearm or wrist pain should be assessed with appropriate radiographic evaluation.

Computed tomography of the elbow may be utilized for further fracture definition for preoperative planning, especially in cases of comminution or fragment displacement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree