Quantifying Trauma System Effectiveness

Gerald McGwin Jr.

The objective of this chapter is to provide an overview of issues related to quantifying trauma system effectiveness. In order to offer a contextual perspective, the chapter begins with an overview of the injury problem in the United States. Following this is a brief description of the history of trauma systems and their development including a summary of the current status of trauma systems in the United States and globally. The chapter discusses measures used to evaluate the effectiveness of trauma systems. The reader should be aware that the following information is not meant to be a systematic and detailed review of published research regarding trauma system effectiveness as such information is abundant. Rather, an overview of our current state of knowledge regarding trauma system effectiveness will be provided with a specific emphasis on the merits of various approaches to assessing it as well as the nature of selected outcomes.

THE MAGNITUDE OF THE INJURY PROBLEM

Injuries represent a significant cause of mortality in the United States. In 2004, unintentional injuries alone were the fifth leading cause of death. Although intentional injuries (including homicide and suicide) have a lower mortality rate, they are among the top ten leading causes of death.1 It is important to note that although fewer overall deaths are attributed to injuries than to chronic diseases such as heart disease and cancer, injuries are the leading cause of death for those aged 1 to 44 years. In fact, injuries represent half of all deaths among children aged 1 to 14 and 73% of all deaths among those aged 15 to 24 years; this is compared to approximately 6% of deaths overall. Therefore, when measured using metrics that account for the unequal age distribution such as years of potential life lost, relative to other causes of death, injuries represent a much larger problem.

Although unintentional injury mortality rates have declined continuously since the late 1970s and early 1980s, recent data suggests that the rate may be increasing.2 A similar pattern has been reported for suicide.3 On the other hand, homicides have experienced a significant increase from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s and then remained high until the mid-1990s when it declined sharply and has remained stable in recent years.4

Although death represents an important barometer for measuring the public health importance of disease, it is rare, relatively easy to measure, and inexpensive-that is, fatal injuries are associated with less medical care costs compared to severe yet nonfatal injuries. The overall incidence of medically treated injuries in the United States is approximately 18,135 per 100,000 (i.e., ≈18%); this is compared to a mortality rate of approximately 53 per 100,000. Since the 1980s, injury-related hospital discharge rates have declined continuously, although in more recent years a plateau appears to have been reached.5

Although the vast majority of medically treated injuries that occur annually are considered minor and do not require hospitalization, the acute and chronic repercussions from these injuries are not insignificant. According to one study, minor injuries account for 80% of the morbidity during the first 6 months after injury and approximately 75% of the estimated lifetime morbidity.6 It has also been estimated that nonfatal medically treated injuries are associated with an average of 11 days of temporary work loss.7 Moreover, most of the estimated $400 billion

in total injury costs in 2000 is attributed to productivity losses.8 For most of those injured there is likely to be little long-term impact; however, for those who sustain serious injuries long-term sequelae will be frequent. Research suggests that return to preinjury function is protracted and that reductions in quality of life are significant.9,10

in total injury costs in 2000 is attributed to productivity losses.8 For most of those injured there is likely to be little long-term impact; however, for those who sustain serious injuries long-term sequelae will be frequent. Research suggests that return to preinjury function is protracted and that reductions in quality of life are significant.9,10

The information presented in the preceding text is useful in two regards; first, it places the injury problem in the proper context, and second, it provides an overview regarding the most commonly used metrics to measure the burden of injury. The latter point is important because this will be the same metrics used to evaluate the effectiveness of trauma systems.

TRAUMA SYSTEMS: DEFINITION AND HISTORY

Trauma System Defined

According to Hoyt and Coimbra, “A trauma system is an organized approach to patients who are acutely injured. It should occur in a defined geographic area and provide optimal care, which is integrated with the local or regional emergency medical services (EMS) system.”11 They further state that, “The major goal of a trauma system is to enhance community health.” These authors also remind us that trauma systems must be viewed as part of a larger public health approach toward reducing injury-related mortality, morbidity, and years of potential life lost. As such it does not exist to provide only optimal care during the acute and late phases of injury, rather it must exist within a multidisciplinary environment and work collaboratively toward reducing injury incidence as well.

Trauma Systems History

Mullins and Nathens et al. describe the development of trauma systems and suggest that their history parallels that of major military conflicts dating back to the late 1700s with the development of the “flying ambulance” that, during the Napoleonic Wars, ferried wounded soldiers from the battlefield to definitive care.12,13 Perhaps the most significant developments in military medicine that have impacted modern trauma systems occurred during 20th century conflicts. During World War I, the injured were evacuated from the battlefield through echelons of treatment facilities, each with greater resources than the prior one; approximately 2 decades later the same protocol was employed during World War II. However, as compared to World War I when the average time from injury to treatment was 12 to 18 hours, during World War II this time interval had decreased to 4 hours, attributable to the increased availability of motorized transportation.12,13 Other changes involved the routine use of blood transfusion during a novel phase of trauma care-resuscitation. Additionally, new surgical techniques for head, extremity, thoracic, and abdominal injuries required that systems for patient triage be developed and implemented. Between World War I and II, the mortality rate from battlefield injuries decreased from 8.5% to 5.8%.14

While a system of progressive levels of care remained in place during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, several changes in resources and the process of care led to a further reduction in the mortality rate to 2.4% in Korea and 1.7% in Vietnam.14 First, the availability of definitive care was moved closer to the battlefield with the use of Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals. Second, the use of helicopters to transport the injured to such facilities resulted in a decrease in the time to definitive care to 2 to 4 hours in Korea and <1 hour in Vietnam. Third, the availability of organized care in the battlefield provided by specially trained medics meant that the process of resuscitation and triage could begin almost immediately following injury.

At the time of the Vietnam War, the collective military experience in treating injured soldiers over the prior 6 decades resulted in an organization of medical resources such that no soldier was more than 35 minutes away from definitive, live-saving treatment.15 Moreover, this experience produced a continuum of care beginning as soon as possible following injury and served as a model for the development of civilian trauma care systems.

The application of the military system of trauma care to the civilian environment was fostered in 1966 with the publication of a National Academy of Sciences report, which highlighted trauma as a public health problem.16 This report called for organized systems of trauma care such that civilian populations might enjoy the same benefits observed among soldiers in combat. It specifically recommended standards for prehospital care, ambulances, and emergency rooms, reflecting the manual on emergency care for the sick and injured of American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma.17 Following legislation by Congress in 1966, the states of Maryland, Illinois, and Florida developed and implemented organized emergency medical systems, trauma centers, and systems. In the 1970s, standards for categorizing hospitals with respect to their ability to provide trauma care were proposed and debated.18,19 This process culminated with the publication of the first edition of the American College of Surgeons Committee onTrauma Optimal Hospital Resources for Care of the Seriously Injured in 1976.20 This document described a categorization scheme for trauma centers and outlined the necessary resources associated with each level in this scheme. The organization of trauma systems, including a description of their specific elements and operation and the resources that define and differentiate the different levels of trauma centers, are beyond the scope of this chapter and such information is readily available elsewhere.11,13,14,21 However, the essential characteristics of a trauma system have been described and they provide a brief yet comprehensive summary (see Table 1).

TABLE 1 ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF TRAUMA SYSTEMS | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

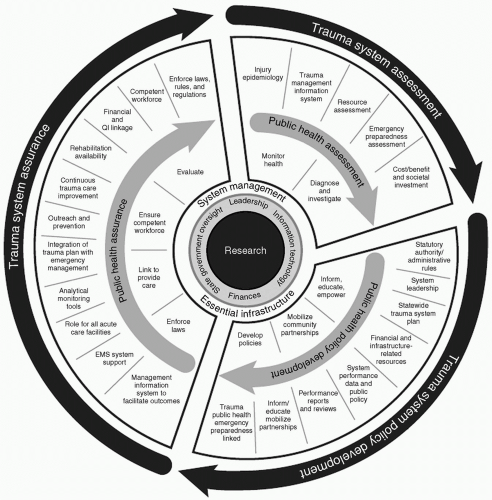

These elements underscore principles published in the American College of Surgeons’ document that make it clear that in order for trauma centers to be effective they must exist within a larger system of trauma care. In fact, when viewed from a public health perspective, the components of a trauma system extend far beyond the process of providing care to critically injured patients (see Fig. 1). This perspective highlights not only the integration of trauma centers with familiar entities such as prehospital care providers but also less familiar individuals such as politicians, health policy specialists, and epidemiologists. Subsequent editions of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma’s document have been published, each reflecting lessons learned regarding the optimal structure and function of trauma centers and systems. This reflects the fact that although the basic elements of trauma systems have not changed over the last several decades, our understanding of their successful implementation is ongoing. The use of technology to more seamlessly link trauma centers within a trauma system represents an important evolution22 as does the integration of automotive technology to further reduce the time to definitive care.23 Finally, it should be noted that contemporary military conflicts represent novel opportunities to further evaluate and refine the provision of trauma care.24

TRAUMA SYSTEMS: EARLY DEVELOPMENTS TO CURRENT STATUS

As described earlier, by the early 1970s there was ample momentum for trauma center and system development and implementation. While this momentum was fueled by political will (and financial resources) and by organizations such as the American College of Surgeons and the American Medical Association, the successful implementation of the early systems likely had a significant impact as well. But perhaps more importantly, that these early efforts produced measurable outcomes provided even more support for trauma system development elsewhere. Following the implementation of trauma systems, Cowley et al. reported a reduction in the mortality rate for seriously injured patients in Maryland;25 a similar reduction was reported by Mullner and Goldberg in Illinois, although this was limited to rural areas only.26 In Jacksonville, Florida, the implementation of an emergency medical care system was associated with a reduction in motor vehicle collision-related mortality.27

These early successes were followed by other important developments. In the late 1970s in Orange County, California a study documented the inadequate care available to seriously injured patients.28,29 Such patients were treated at a large number of hospitals, none of which were presumably dedicated to the care of such patients. Approximately three quarters of trauma-related deaths were judged to be preventable, this is compared to 1% of such deaths in San Francisco, California, where seriously injured were treated at a single institution. As a result, a trauma system was developed and implemented in Orange County, California and the care of critically injured patients was limited to just five trauma centers; subsequent studies reported significant reductions in injury-related mortality.30,31 The experience of Orange County, California is important not only as an example of early trauma system implementation but perhaps more importantly as an example of the role of data for future trauma center and system development. That is, the Orange County experience underscores the importance of quantifying the injury problem in a community as an integral part of assessing the need for a trauma system. Although routinely quantifying trauma system effectiveness is vital, evaluating outcomes before system implementation is crucial for planning purposes and such information serves as a baseline against which postsystem outcomes can be compared. In fact, in the late 1970s and mid-1980s trauma systems developed in San Diego, California and Portland, Oregon took a similar approach to that used by Orange County, California.32,33,34,35,36 Trauma system development and implementation in these two areas were viewed as a public policy issue and, as such, quantifying the injury problem served to highlight a need as well as demonstrate success following implementation.

By the late 1980s, only 2 states had all the essential components of a trauma system (Table 1) and 20 others had some of the components; 29 states had not begun the process of developing trauma systems.37 Approximately 10 years later a report indicated that the number of states that possessed all of the essential components of a trauma system had risen to 5; however, only 14 had developed and implemented some of the components, a decrease since 1988.38 By 1998, the picture had become more encouraging. Although the number of states with all essential trauma system components remained at 5,

the number with some components had increased to 38.39 In 2005, Mann et al. reported that 8 states met all trauma system criteria, 27 had some criteria, and 14 had none.40 Focusing on trauma center versus trauma system resources, MacKenzie et al. reported that in 2003 there were 1,154 trauma centers (190 Level I and 263 Level II) in the United States.41 (It is perhaps important to note that the definition of a trauma center varied widely.) This represents a more than twofold increase since 1991 when there were a reported 471 trauma centers.42 During this time, the largest increase has been in Level III and Level IV/V centers, although Level I and II centers increased by 21%. Geographically the expansion of trauma center resources has not been uniform, with the south experiencing a greater increase than other areas.

the number with some components had increased to 38.39 In 2005, Mann et al. reported that 8 states met all trauma system criteria, 27 had some criteria, and 14 had none.40 Focusing on trauma center versus trauma system resources, MacKenzie et al. reported that in 2003 there were 1,154 trauma centers (190 Level I and 263 Level II) in the United States.41 (It is perhaps important to note that the definition of a trauma center varied widely.) This represents a more than twofold increase since 1991 when there were a reported 471 trauma centers.42 During this time, the largest increase has been in Level III and Level IV/V centers, although Level I and II centers increased by 21%. Geographically the expansion of trauma center resources has not been uniform, with the south experiencing a greater increase than other areas.

Underlying the improvement in the availability of trauma care resources in the United States is the question, how much is enough? It has been suggested that one to two Level I or II trauma centers per million population is adequate.43 This same study indicated that in the

35 states with formal trauma systems most meet this criterion, whereas in those without formal trauma systems, approximately 50% do. Therefore, despite the fact that trauma care resources are more abundant and better organized than at any time in the past, Nathens et al. calculated that more than one third of major trauma cases in the United States is received at institutions not formally designated for trauma care.43 Branas et al. reported similar findings and additionally noted that this problem is greater in rural compared to urban areas.44 It is perhaps important to note that the availability of trauma care resources in the United States is discordant with the public’s perception and expectation of the availability of these same resources.45

35 states with formal trauma systems most meet this criterion, whereas in those without formal trauma systems, approximately 50% do. Therefore, despite the fact that trauma care resources are more abundant and better organized than at any time in the past, Nathens et al. calculated that more than one third of major trauma cases in the United States is received at institutions not formally designated for trauma care.43 Branas et al. reported similar findings and additionally noted that this problem is greater in rural compared to urban areas.44 It is perhaps important to note that the availability of trauma care resources in the United States is discordant with the public’s perception and expectation of the availability of these same resources.45

Finally, although much of the material presented herein is in reference to the United States, trauma center and system implementation and development is active elsewhere in the world. A recent issue of the journal Injury provides an overview of trauma care systems in many other countries including Australia, China, Germany, and South Africa, among others.46 There are opportunities to learn from the experiences of these countries, particularly those that have faced many of the challenges currently facing future trauma system development in this country.

MEASURING TRAUMA SYSTEM EFFECTIVENESS

General Considerations

It is important to place trauma system effectiveness within a larger context of the injury problem and the natural history of approaches to address it. This context helps provide perspective regarding what is meant by the word “effectiveness” when evaluating trauma centers and systems. It has been demonstrated that trauma systems are part of a larger approach to reducing the burden of injury that include injury prevention initiatives among others. Despite this, the success of trauma system, at least as described thus far, has been measured on the basis of mortality. Although mortality is clearly the most significant outcome that one might experience, there are many nonfatal outcomes and several non-health-related outcomes (e.g., quality of life, financial) that are important. These nonfatal and non-health-related outcomes will be discussed in turn.

Reflecting upon the definition of a trauma system provided by Hoyt and Coimbra, one should recall that, “The major goal of a trauma system is to enhance community health.”11 With respect to mortality, “community health” can be taken to mean the number of injury-related deaths per population. As will be discussed subsequently, many studies have used this very measure to quantify trauma center and/or system performance. Yet, a population-based injury mortality rate comprises two separate entities:1 injury incidence (injury episodes per population) and2 injury case fatality (deaths per injury episode). A public health approach suggests that primary prevention (i.e., injury prevention) initiatives, valid components of a trauma system, seek to impact the incidence of injury, whereas tertiary prevention initiatives (i.e., the provision of organized and appropriate trauma care) seek to impact injury fatality rates. However, although primary prevention is viewed as an important element of a trauma system per se, the reality is that most systems function with the goal of tertiary prevention. This is important to keep in mind when evaluating studies reporting population-based injury mortality rates; the reality is that trauma centers are likely impacting but one component of these rates.

It is also important to note that trauma centers and systems cannot prevent all trauma-related deaths. The trimodal distribution of trauma deaths was first described in 1983.47,48 As a function of elapsed time after injury, deaths from traumatic injury were classified as generally falling into one of three categories: immediate, early, and late. Immediate deaths were those that occurred <1 hour following injury, making up approximately 50% of the total; early deaths occurred within the first few hours of injury and accounted for 30%; and late deaths occurred days to weeks following injury and were 20% of all trauma deaths. Immediate deaths were largely due to neurologic injury (brain, brain stem, and spinal cord) or laceration of the heart or major vessels and classified as not preventable. Early deaths were largely due to severe blood loss from the head, respiratory system, and abdominal organs. These deaths were largely treatable and therefore possibly preventable. Finally, most late deaths were due to infection and multiorgan failure. Reducing the number of injury-related deaths during each period largely relies on expedient and optimal medical care, although less so for some periods than others. For example, injury prevention efforts are likely to be important for reducing immediate deaths, whereas trauma systems should have the greatest impact for early and late deaths.

And finally returning to nonfatal and non-health-related outcomes, although rarely evaluated in the literature, such measures are important when considering trauma system effectiveness. They are, however, more difficult to measure than deaths and in some instances they make suggest worse performance following trauma center/system implementation. For example, patients with major injuries who receive appropriate and timely care at a trauma center have improved chances of survival compared to similar patients treated at nontrauma facilities. However, care may be protracted for such patients and, related to this and their extensive injuries, their risk of complications is increased. Therefore, attempts to quantify trauma center/system effectiveness in terms of complications may find such rates elevated following implementation or compared to nontrauma facilities. A similar illustration could be made for length of stay and cost of care. Although appropriate study designs and statistical tools can help account for

such changes or differences in patient characteristics within and between facilities, recognition of the potential for such seemingly unexpected is important.

such changes or differences in patient characteristics within and between facilities, recognition of the potential for such seemingly unexpected is important.

The following sections will provide an overview of research regarding trauma system effectiveness according to various metrics (e.g., deaths, complications).

Mortality

A comprehensive review of trauma system effectiveness was published in 1999 in a supplement to the Journal of Trauma that served as the proceedings for a meeting, commonly known as the Skamania Conference, on the current state of trauma systems. Mann et al. summarized the literature on trauma system effectiveness published as of May 1998 and separated this work into three categories: panel studies, registry comparisons, and population-based studies.49

Panel Studies—Design and Interpretation

MacKenzie has reviewed the strengths and limitations of the panel study approach to trauma system assessment as well as provided a review of the literature as it existed at the time (i.e., 1998).50 Generally described, these studies utilize a group of experts, that is the panel, to judge whether a group of deaths were potentially preventable and the role of specific errors that led to such deaths. Panel studies were among the first approaches used to demonstrate the need for trauma systems and to demonstrate their effectiveness. Early panel studies utilized subjective implicit criteria to determine whether deaths were potentially preventable and relied upon panels that were small in number. Inconsistent results across studies can be attributed to the less than rigorous conduct of these early studies. Indeed a lack of clear definitions regarding preventability and heterogeneous patient populations have been shown to result in low inter-rater reliability of judgments regarding preventability.51 However, when designed and executed correctly panel studies can provide strong evidence regarding trauma system effectiveness. Therefore, how does one accomplish this task?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree