19 PSYCHOSOCIAL IMPACT OF TRAUMA

In the midst of an acute emergency or critical care situation such as a traumatic injury, the nurses’ immediate priority is to physiologically stabilize the patient. In the fast-paced, high-stress environment of the emergency department (ED) and the intensive care unit (ICU), it may seem that there is little time for anything else and the mental health needs of the patient and their loved ones can be easily overlooked. However, taking the time to address these issues may prevent psychologic morbidity. During and often long after the acute health issues have been resolved and wounds have healed, the minds of those involved may still be suffering. The psychologic impact of the illness experience for all involved must be acknowledged and addressed.

A traumatic injury often precipitates a crisis for both the patient and family. They feel vulnerable, overwhelmed, and ill prepared to deal with the ramifications of the injury. Outcomes are uncertain and difficult decisions must be made. The patient and family find themselves in a situation over which they have little control. Psychologic consequences of traumatic injury can often lead to long-term complications such as social isolation, job loss, economic problems, and decreased pleasure in leisure activities. In addition, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other psychologic morbidity contribute to postinjury functional limitations. Long-term ramifications of trauma are significant, leaving many patients and families with long-lasting psychologic scars.1–5

TRAUMA AS A CRISIS

Crisis is defined as an acute emotional upset that may interfere with the ability to cope emotionally, cognitively, or behaviorally, rendering the person unable to solve problems by usual devices.6 The often violent and unpredictable nature of traumatic injury certainly can precipitate a situational crisis for the patient and family. Because the initial traumatic injury often precipitates other stressors and the need for continuous adaptation, crisis may occur at any point along the continuum of care. Initially, during the phases of resuscitation and critical illness, the crisis may focus on whether the individual will survive the injury. Later, during the intermediate phase, the patient and the family may experience a crisis as they attempt to adjust to physical or emotional disabilities. During the rehabilitation phase, crisis may ensue as the patient and family face the difficulties of reintegrating the injured individual into the family and the community.

Infante7 proposes a model of crisis that provides an understanding of crisis production and the potential for growth after the event. Before being injured the individual has a level of function that allows management of his or her daily needs and provides a sense of equilibrium. The individual suddenly experiences a hazardous event, perhaps a traumatic injury, and attempts to deal with the event by using familiar coping mechanisms, which have been effective in the past. In the current situation, however, these coping mechanisms prove to be inadequate, resulting in crisis. This crisis may result in the individual functioning at a lower level than before the crisis, and prolonged crisis without appropriate intervention can be devastating to the individual. He or she may experience disruption of the family, divorce, depression, or failure to return as a productive member of society. Interventions by the trauma nurse, however, can produce more positive outcomes. A realistic goal of crisis intervention is resolution and restoration to at least the precrisis level of functioning. Resolution is possible through the acquisition of new skills and the adoption of enhanced coping mechanisms. A crisis, effectively managed, can strengthen adaptive capacity, promote growth and learning, enhance problem-solving abilities, and result in a higher level of functioning. This potential growth depends on the timing and appropriateness of interventions.

CRISIS INTERVENTION

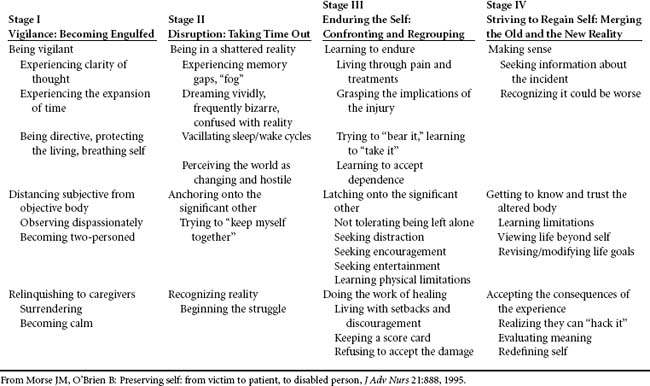

The focus of crisis intervention is to address the immediate problem or issue that is precipitating the crisis for the patient or family. It begins with an assessment of the person’s view of the situation and what resources he or she has to cope with the stressor involved. Aguilera8 presents a model of crisis intervention that incorporates three critical factors of crisis: (1) perception of the event, (2) adequacy of situational supports, and (3) effectiveness of coping mechanisms. Balancing these critical factors determines whether an event will produce a crisis for the individuals involved (Figure 19-1). When caring for an individual experiencing a crisis, assessment of the three balancing factors will provide direction for intervention. A deficit in one or more balancing factors places the individual at risk for crisis. For example, after a traumatic spinal cord injury, Patient A may perceive the event as being completely overwhelming and one with which he can never cope. He may have functioned in isolation in the past and may feel that there is no one on whom he can call for support. In addition, he may have a history of heavy alcohol use and poor coping abilities, providing him with few effective coping mechanisms to deal with the current crisis. Patient A demonstrates deficits of all three balancing factors and is at risk for crisis development. Appropriate interventions would assist him to establish a more realistic perception of the event, use appropriate situational supports, and identify effective coping strategies. By providing support in each area of deficit, the nurse strengthens Patient A’s balancing factors, reduces tension, and effectively intervenes to prevent a crisis. In contrast, Patient B has a similar spinal cord injury. This patient, however, views her injury as a challenge, one she can overcome with support from the environment. In the past Patient B has established a solid support system of friends and family on whom she can call on for help with the current event. In addition, her strong faith has assisted her to cope with past stressors and is also effective with the current stressor. Because Patient B has strengths in all three balancing factors, she is not currently crisis prone. Appropriate interventions would include support of her current resources and identification of future events that might generate a crisis.8

FIGURE 19-1 Paradigm: the effect of balancing factors in a stressful event.

(From Aguilera D: Crisis intervention: theory and methodology, p. 33, St. Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

PERCEPTION

The first balancing factor is perception. Perception is defined as the subjective, individualized meaning of the stressful event and is determined by the individual’s unique way of taking in, processing, and using information from the environment.8 When confronted with an event, the individual will first perform a primary appraisal. This process allows the individual to judge whether the outcome of the event will be a threat to significant future values or goals. A secondary appraisal is then performed to determine the range of coping behaviors needed to either overcome the threat or achieve a positive outcome. If, during the appraisal stage, the stressor is perceived to be too overwhelming and not able to be handled successfully with available or typical coping mechanisms, the individual may feel forced to deny, distort, or repress the reality of the situation to cope. If, however, the appraisal process indicates that the available coping mechanisms are adequate to meet the threat, more efficient coping mechanisms may be used. If the individual distorts or denies the reality of the event, attempts to deal with the stressor will be unsuccessful, tensions will escalate, and the stress will not be reduced.8

Intervention is directed toward determining whether the individual’s perceptions are realistic or distorted. If perception is found to be realistic, support of the perception is indicated. However, if perception is distorted, it is important to use education and support to assist the individual to redefine the perception.

SITUATIONAL SUPPORTS

The second balancing factor, availability of situational supports, focuses on the evaluation of the availability of individuals in the environment who can be counted on to assist in the management of the problem. The individuals may include family members, friends, health care workers, support groups, and church or community resources. Adequate situational supports provide the individual with a source of advice, advocacy, and strength. Inadequate situational support, however, leads to feelings of isolation, loss, and vulnerability. The individual then experiences increased stress and a sense of overwhelming isolation.8

• Are there people in your family or in your community on whom you can depend or call on for help right now? Who are they?

• Can/should they be contacted?

• Who is your most comfortable source of support?

• Do you have a higher power that you can call on for strength?

COPING

The third balancing factor, availability of effective coping mechanisms, focuses on the usefulness of current coping mechanisms to deal with the stressful event. Typically individuals use a spectrum of coping mechanisms on a daily basis to handle perceived stressors. These coping mechanisms may include prayer, exercise, discussion, or crying. Others include smoking, alcohol or drug use, verbal battles, anger, swearing, or violence. When confronted with a stressor, the individual attempts to deal with it by using familiar coping mechanisms that have been effective in the past. A crisis is initiated when the individual realizes that these coping mechanisms no longer reduce the stress or provide resolution of the event. This perception of inadequate coping leads the individual to feel overwhelmed. Tension and anxiety increase, and a crisis ensues. The goal of intervention is to assist the individual to delineate methods of new or previously used coping methods to decrease anxiety and enhance coping.8 When an individual is assessed for adequacy of coping mechanisms, it is useful to ask the following questions:

• Have you ever experienced anything like this before?

• How is this situation similar or different?

• Have you ever coped with high-anxiety situations in the past?

• What did you try? What worked? What didn’t?

PREVENTION

Injuries are among the leading cause of death and disability in the world. Road traffic crashes, falls, interpersonal violence, and self-inflicted wounds are the most prevalent injuryrelated causes of morbidity and death.9 Motor vehicle crashes, firearm incidents, poisonings, suffocations, falls, fires, and drownings take the lives of more than 400 Americans each day.10 The Healthy People 2010 initiative has targeted these traumatic events as areas for intervention and prevention in the current decade. The use of safety devices such as seat belts in cars and helmets for bicyclists and increasing awareness for home safety issues including fall prevention and firearm safety were emphasized as specific interventions that would decrease the number of traumatic injuries or deaths. Characteristics of at-risk individuals and families are presented.

PERSONS AT RISK FOR TRAUMA

Age, sex, race, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors all correlate with the likelihood of traumatic injury. For example, the young and the old are most vulnerable to fall-related injuries, men are most often the perpetrators and victims of homicide, and African-Americans are seven times more likely than whites to be murdered.10 Injuries sustained in road traffic crashes are the leading cause of death worldwide among youth aged 15 to 44 years.9 Choices to engage in more risky activities such as sport events or to use mind-altering substances also increase the risk for traumatic injury. For teens, sports and recreation are the most common activities associated with injury. Not surprisingly, high material wealth is positively correlated with sports injuries, whereas poverty is positively correlated with fighting injuries.11 Low income, discrimination, and lack of education and employment are factors that are also closely associated with violent and abusive behavior.10

The high rate of recidivism in trauma care has prompted researchers to attempt to identify social and psychologic factors that increase the risk for traumatic injury. Poole et al12 attempted to identify the relationship between specific psychosocial factors and the likelihood of traumatic injury. It was discovered that individuals experiencing a traumatic injury are most likely young men who have not graduated from high school. Patients with intentional injury have a higher rate of illicit drug and alcohol use than do those with a nonintentional injury. In addition, patients experiencing intentional injury have a higher unemployment rate than those with nonintentional injury. The average intelligence score for victims of intentional injury is lower than both the national median and the scores of nonintentional trauma victims. Psychopathology is evident in the intentional trauma group, with 63% of the sample meeting diagnostic criteria for psychiatric diagnoses, including antisocial personality, depression, illicit drug abuse, and mental retardation. Results from this study indicate that, for some individuals, traumatic injury may not be a random accident but rather a result of the victim’s high-risk behaviors and level of psychopathology. Social forces, such as unemployment and low education levels, may also influence the potential for traumatic injury.12

It is well known that alcohol use is a contributing factor in traumatic injuries. Forty percent of motor vehicle fatalities are alcohol related.13 Ankney et al14 analyzed the relationship among selected medical, social, and psychologic factors and alcohol-related trauma in a rural population. Their findings suggest that there are significant differences in the psychologic and social factors and medical histories of trauma victims with positive blood alcohol content (BAC) versus those with negative BAC. Patients with positive BAC were significantly more likely to be male, aged 21 to 50 years, unemployed or who had recently changed job status. In addition, this population was frequently known to the criminal justice system in that they reported a history of more arrests and criminal charges than did the BAC-negative group. The BAC-positive group also had an increased rate of inpatient mental counseling and positive drug screens. The finding that an increased number of BAC-positive patients reported having incurred a traumatic injury in the past reinforced the concept of recidivism. Several other factors approached statistical significance for the BAC-positive group: recent conflicts, interpersonal problems, or criminal sentencing; changes in financial status; and significant personal changes. The researchers conclude that trauma patients with premorbid alcohol abuse should be targeted for treatment in an effort to reduce the risk of recidivism.14 Unfortunately, the majority of trauma patients rarely receive referral for substance abuse treatment.15 Trauma nurses can play a key role in initiating such referrals. Trauma center administrators can set policy that requires intoxicated trauma patients to receive interventions. Research has demonstrated success in such referrals.13

AT RISK FAMILIES

Levels of Chronic Anxiety

Dysfunctional coping styles render families more vulnerable to crisis. Examples of these include very intense relationship systems: highly positive, highly negative, conflicting, or a combination. They are frequently characterized by a lesser ability to distinguish feeling process from intellectual process and are caught in a cycle of automatic emotional responses to each other, over which they perceive they have no control.16,17 Behaviors are reactive and impulsive, with the goal of “feeling better” being paramount. Emotional responses are frequently chaotic and repetitive, reflecting a controlled, rigid, and limited repertoire of skills with which to deal with one another. In these families chronic anxiety tends to be absorbed by one family member, and that individual comes to be focused on in excess of either positive attention (i.e., “golden girl”) or negative attitudes (i.e., “black sheep”). In this way the level of chronic anxiety between two family members, such as spouses, is somewhat lessened by the focus and diversion of energy onto a third person in the system. The member who is focused on in this way is the one who comes to be the most at risk for development of physical, emotional, and social problems throughout life.17

Emotional Relationship Structure

In times of high anxiety, dysfunctional ways of relating become even more intense. Families that tend to have a predominantly fixed and inflexible relationship structure dominated by dependence and excessive need for approval from one another will most likely react to crisis by automatic instinctual emotional forces rather than by use of intellect.17 The concept of being enmeshed with another person implies that boundaries are diffuse and that the behavior of one family member has a direct effect on those with whom he or she is enmeshed.18 Relationships tend to get fixed around one person underfunctioning in most of life’s tasks and another reciprocally overfunctioning; there comes to be very little, if any, reciprocity within this pattern (i.e., one person always underfunctions and one always overfunctions). Members of this type of enmeshed, emotionally based family feel responsible for what another feels, whereas they do not feel much responsibility for themselves. Rather than being sensitive to another, these individuals find that they allow their behaviors to often be determined by another’s desires. There is a problem distinguishing “needs” from “wants,” and although family loyalty is rewarded, there may be an overall low caring index on the part of individuals for one another.

Communication Process

Crisis-prone families have few hierarchical boundaries and rules between the generations in communication and tend to be sensitive to praise or criticism for one another.18 Communication sequences are predictable, rigid, and reactive, with low levels of conflict resolution. Confrontation of issues tends to be avoided, and many conflicting issues either are never discussed or are fought about but never resolved. Communication is closed, with little taking in of new information, and is impoverished in affect. Generalizations are frequent, and blaming is heavily used to hold someone in the family, the school, the law, the society, or the institution at fault.17 Others are often told what to do rather than being encouraged to find their own solutions.

Multigenerational Heritage and Patterns

Often crisis-prone families are cut off from previous generations, being either geographically distant or, more frequently, emotionally disconnected.17 Boundaries around the family are closed, with little relationship network or few social supports available to help diffuse the family’s chronic anxiety. There is a strong passing down of family “myths” and expectations for behavior and feelings on the part of individuals. Most often there are multigenerational patterns of various physical, emotional, and social dysfunctions such as chronic physical illnesses, depression, violence, substance abuse, and repeated trauma.

In summary, adaptive coping is enhanced with low to moderate levels of anxiety, which allows the family to hear, understand, and repeat information; decreased reactivity to issues, which allows action rather than reaction and the adoption of a solution-oriented approach; high motivation and sense of personal identity distinct from an enmeshed identity with the patient; ultimate belief in one’s ability to gain control over one’s life again; and evidence of role flexibility and high levels of family caring and cohesion.8,17

RESUSCITATION PHASE

THE PATIENT

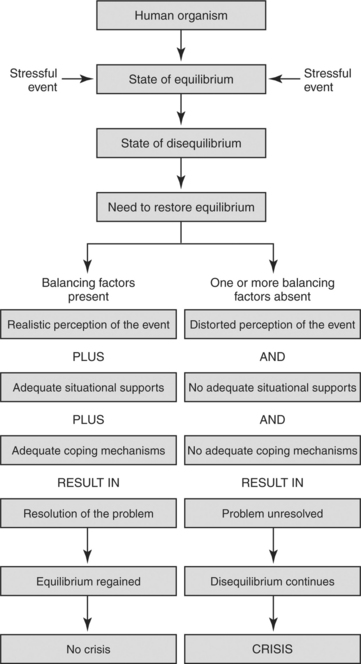

During the resuscitation phase the trauma victim feels an instantaneous, overwhelming threat to life. A study by Morse and O’Brien19 describes a four-stage process of self-preservation experienced by trauma victims (Table 19-1). The first stage of the process begins at the time of injury, and the remaining stages continue to the point of recovery.19

The first stage of the self preservation model is termed Vigilance: Becoming Engulfed. During this stage the trauma victim initially has a significant increase in cognitive abilities. There is a heightening of senses, and survivors are able to provide extremely detailed descriptions of the incident. Time seems to slow, and the individual has difficulty with the sense of time. For example, the patient may relate that the extrication from the vehicle took hours, when in fact it took only minutes. The trauma victim often recalls the exact moment of impact of the traumatic event and immediately becomes aware of the seriousness of the injuries and that his or her life is in danger. During the prehospital phase the conscious individual becomes an active participant in his or her own care, instructing bystanders who are attempting to assist in the initial rescue. He or she will, however, relinquish control to the paramedic team if they appear to be competent.19

I remember lots of nurses and doctors or whatever around me. I don’t remember feeling pain. I remember hearing a woman screaming for _______, who was my son who died 9 years ago. I remember wondering, “Who is that woman screaming for my son? Doesn’t she know he’s dead? Doesn’t she know he died 9 years ago? Why is she screaming?” I could feel that it was actually me screaming and I remember thinking, it’s not _______ you want. Why aren’t you screaming for _______ and _______?19

Visual input generates fear for patients. They may have only their own damaged body to explore; the sight of tubes and machinery to which they are attached contributes to increased anxiety. If they are able to see other patients, their visual sense will be bombarded by the overwhelming mutilation of others around them. Privacy is minimal and control nonexistent. As the stage of intense vigilance ends, the individual may experience gaps in conscious awareness. These gaps may be a result of administered sedating agents or analgesics or deterioration in the patient’s physical state.19

The intensity and degree to which the injury and resuscitation process affects the patient depend largely on the person’s perception and appraisal of the situation and the level of intactness of the person’s biopsychologic state. Hence, response to traumatic injury is not directly related to the severity of the injury but to the unique perception and interpretation of events and stressors and the coping strategies trauma patients are able to call forth. In effect, then, it is feasible that a minimally injured trauma patient may in fact experience and respond more intensely to stressors than a severely physiologically impaired person. The inverse also is possible: the more severely injured the patient is, the less able he or she may be to mediate the stress. It becomes clear that the nurse’s assessment and understanding of the patient’s perception of stressors are what guide interventions, not simply the severity of the injury.

THE FAMILY

During the resuscitation phase the family also experiences a state of crisis after the injury of a loved one. Fear and uncertainty regarding the severity of the patient’s condition and lack of communication from the trauma team produce increased stress.20 The stress inherent in an unfamiliar complex trauma environment and the often unstable, unpredictable nature of illness/injury can lead to enormous strain and places the family at risk for a difficult adaptation. The uncertainty of prognosis, financial concerns, role changes, disrupted daily routines, and a family’s prior ability/success at managing stressful situations all affect the overall family well-being. The severity of the patient’s illness/injury may be associated with a complicated, prolonged recovery, resulting in a delay in or inability in achieving an acceptable level of functional recovery. Early family contact, frequent updates and assurances (when appropriate) help foster an understanding of the situation and reduce stress. Crisis assessment and intervention is indicated with families of trauma patients.20,21

Assessment of the family not only involves taking into consideration the immediate needs for assistance and direction with acute crisis, but also requires an intervention framework that assists the family toward enhanced self-reliance and functional coping. The skills needed by the nurse during this acute phase incorporate a mixture of crisis intervention and beginning family system assessment as family members are struggling with the uncertainty of whether their loved one will survive or what life changes may occur if he or she does survive.

Having family members present during the resuscitation phase remains controversial. Supporters believe that this is an opportunity to educate the family in a real-time/real-life situation about the medical issues confronting both their loved one and the health care team. Having the family present allows them to see and appreciate the efforts and care being provided, to understand that every reasonable effort was being attempted, and to provide them with closure to the experience. Opponents claim that having the family at bedside during resuscitation creates dangerous congestion at an already crowded bedside and that family members could become too emotional and interfere with care. The family’s presence could increase caregiver stress, making them more tentative in their decisions and pressured when performing procedures. Fear of increased litigation and maintaining patient confidentiality are other often citied concerns.22 Halm,22 in a review of the literature, found that although families often stated a desire to be present during resuscitation efforts, whether this would have been acceptable to the patients themselves was unknown, raising significant ethical and legal issues.

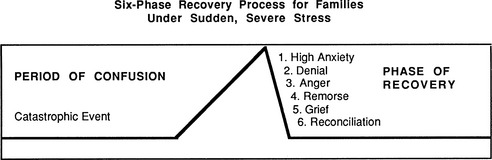

In a classic study of families of trauma victims, Epperson23 identified a six-phase recovery process that families under severe and sudden stress undergo. How individuals within the same family respond remains unique and diverse, although there does seem to be an identifiable course that is common (Figure 19-2).

FIGURE 19-2 Six-phase recovery process for families under sudden, severe stress.

(From Epperson MM: Families in sudden crisis: process and intervention in a critical care center, Soc Work Health Care 2:205-273, 1977.)

Anxiety, Shock, and Fright

During periods of high anxiety, family members often need repeated clarifications and restatements of information. This information should be brief, explicit, and straightforward, and it may be more useful if it is actually written. To accurately ascertain that the family has heard what was being said, they should be asked to repeat what they understand at various points, what they have been told, and what that means to them. Even the most functional families may become dysfunctional for a time in light of enough stress, and an initial period of confusion and the need for precise reinforcement and repetition of information are normal. Often the identification of one key family member with whom the health care team communicates regarding the patient’s status is useful in limiting the confusion and defusing some of the anxiety.23

Denial

Denial within the resuscitation phase serves a somewhat useful purpose for family members in that it may provide the time necessary to adapt and adjust to the actual reality of what has happened.23 Denial, as such, buys the family “psychologic time.” The nurse needs to recognize the purpose and function of denial while at the same time recognizing the family’s need to deal with the reality of the present situation and still maintain hope. Statements such as, “Mrs. _____, your daughter has never been ill before and I know it must be very difficult for you to believe that she is in a coma from the car crash” are often useful. In this way the message is transmitted that the nurse is aware of the struggle between what is hoped for and what is the current reality.

If denial is prolonged and hampers the carrying out of necessary actions on the part of family members, additional interventions may have to be incorporated that are more directly unsupportive of the denial and much more directive and confrontational. In the case of one 36-year-old mother of an 11-year-old daughter who was a drowning victim and had been in a coma with no physiologic indication of functional improvement, the mother waited by the bedside every day for the child to wake up. She would say, “I just know that today Claudia’s going to open her eyes and be OK.” Her denial stemmed from the fact that the daughter’s friend, who was with her and also had drowned and been initially unresponsive, had begun to respond and improve 3 weeks after the initial accident. Also, on the news that month was the story of a woman who had awakened after 11 years in a coma. Hence the mother’s natural inclination toward denial and hope was buttressed by two cases evidencing improvement. However, given all medical indications, this was not predicted for Claudia, and her mother would make no perceptible move to investigate the possible institutional placements made available to her by the nurse and the rest of the team. A decision had to be made, and the mother had to be gently but firmly told that her daughter’s case was different from the other little girl’s. Clear distinctions were made in easily understandable terms as to the differences in initial signs and symptoms and the sequencing of return of function. She was shown visual pictures of the extent of brain damage and told that all indications of what was known at this time indicated that this was the state in which Claudia would remain. Hope is an important ingredient and should not be totally removed, but to break through prolonged denial that may become pathologic, a factual representation is essential, along with the notion that miracles are always possible; in this case that is what was necessary.23 In such cases of dysfunctional denial, a team approach is recommended to ensure that a solid plan of care is constructed and a consistent message is given.

Anger, Hostility, and Distrust

Families need to be able to verbalize their anger without the health care professional personalizing it; they may be angry at the patient, at themselves, at the institutions giving care, at the physicians, at the nurses, at God, at society, and at life in general. Diffuse anger is often present and helps forestall the pain inherent in the grief that follows. Anger needs to be given expression and accepted by the nurse, while at the same time direction is given in the form of questions that help families identify the actual legitimacy of the focus of their anger. When the “real thoughts behind the anger” can be pulled out by the family, they often realize that fear, guilt, and loss of control are driving the anger. They can then put that to rest and move on with the necessary grief work before reconciliation.23

Remorse and Guilt

Epperson23 refers to the remorse stage as the “if only” stage. Families struggle with sorrow and guilt over the part they played in the trauma or injury or in not preventing the possibility of it. It is important not to rationalize this phase as problem-solving questions are asked to help families reason out the thoughts, fears, and misperceptions they have. A mother’s remorse and guilt over allowing her 19-year-old son to buy and ride the motorcycle on which he was struck by a truck should be listened to without judgment and without rationalization. Statements and questions such as, “19-year-olds make their own choices,” “No family is without conflict,” and “Is it possible for even a mom to control a 19-year-old’s behavior?” may be helpful in this phase. The more verbalization the better because this will defocus the issue and work toward problem solving. However, bear in mind that wide fluctuations in mood are normal within these early phases. Many family members share the fear that they are “going crazy” because of the lability of their emotional responses during the resuscitation and critical care phases, and it is crucial for the nurse to share the “norm” in ranges of feelings experienced by most families in similar situations.23

Grief and Depression

Watching a family experience the necessary pain of the grief phase is especially difficult. Too often nurses intervene too rapidly to support, take care of, fix, or make better. Pain is a necessary component of grief work, and it must be allowed to run its course. To the extent that the nurse can be comfortable with staying connected to those family members who are grieving and are in great pain, the essential work for families within this phase will be augmented. This, in turn, allows the mobilization of resources and the realistic putting together of family life required for reconciliation. Table 19-2 summarizes the basic interventions for each of these initial family responses within the phases of recovery after a crisis.24

TABLE 19-2 Interventions for Initial Family Responses to Crisis

Modified from Kleeman KM: Families in crisis due to multiple trauma, Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 1:23-31, 1989.

Throughout these phases, the art of nonjudgmental listening is essential. It is easy to allow oneself to get pulled in by emotions to giving too much support, assuming too much responsibility for others’ feelings, siding, and blaming. Nontherapeutic responses, questions, and statements made by the nurse such as, “You shouldn’t blame yourself,” “How can you think you caused that to happen?” “Things will work out,” “All things happen for a reason,” “God does not give us more than we can handle,” and “I would agree that ____________ was wrong to do that!” do nothing to assist in long-term coping and may do much to alienate the nurse from the family he or she is endeavoring to support. It is not important to know the answers to many of the unanswerable questions that families pose but rather to ask the right questions so that families may begin to generate their own solutions, coping mechanisms, and resources. Questions such as “I hear what you say about ____________; how do you see that as changeable?” “What would it take for you to feel less guilty? less hostile? less ____________?” “How will your family pull together to ensure that everyone will be okay after this loss?” are examples of the types of thought-producing stimuli that facilitate the family’s own problem solving and ensure the transmission of a nonjudgmental attitude on the part of the nurse.

Trauma centers must have a systematic process for accommodating and supporting large or extended families. This process must include sensitivity to cultural norms during times of crisis and illness and include discussion about how the family makes decisions and communicates information, especially during the acute phase of trauma care.

CRITICAL CARE PHASE

THE PATIENT

During the critical care phase, the trauma victim enters stage II of the process of self-preservation as described by Morse and O’Brien19 (see Table 19-1). Stage II, defined as disruption: taking time out, is described by trauma survivors as an overwhelming phase with which they had difficulty coping. The stage is often described as consisting of episodes of vivid, terrifying dreams interspersed with periods of excruciating pain. Burn patients in particular were found to experience the most terrifying and confusing of dreams. One patient describes his experience as follows: “I had a nightmare of this little kid. I was in Vietnam and I was half blown away and this kid dragged me to his mother and his mother dissected a cow and used the cow’s parts and put me back together.”19

Patients with spinal cord injuries with deficit often dream of the “old me,” a dream in which the patient is intact and fully functional. On awakening, the patient is suddenly again confronted with the reality of the injury. Patients in this stage also describe intense difficulty defining reality, uncertainty as to which event is real and which is only a dream. Both sleep and wakefulness are described as being intolerable. Patients describe this period as a vicious cycle wherein they attempt to escape from the terrifying sleep state by awakening and, in contrast, escape from the pain by sleeping. The result is a state of confusion or fog in which the patient cannot determine wakefulness from sleep or sometimes life from death. During this stage, patients are most often in critical condition, receiving pain medication and sedation, both of which contribute to the confusion. The period is often recalled as one of vague, dreamlike memories or flashbacks. Patients experience altered perceptions of the environment, believing that the furnishings of their rooms are changed frequently or that they have been moved from room to room. Health providers are often viewed as hurtful, hostile, and not to be trusted. Patients report that they expected their family members to protect them from these caregivers and are hurt and confused when the family leaves at the end of the visiting session.19

During stage II a critical need expressed by trauma survivors is to have family members readily accessible. Patients view their family members and significant others to be essential sources of support and a safe haven in their world of pain and confusion. Often the patient is afraid to be alone and the significant other represents a sense of security, reality, and safety. The family member helps anchor the patient to reality, assists the patient to regain a sense of self and “humanness,” and contributes to the healing process. Patients describe the presence of a family member as being the most important intervention during stage II.19

Alteration of Body Image

In a society in which youthful physical attractiveness is valued, disability, disfigurement, and scarring are likely to produce anxiety and problems with self-esteem. Sudden changes in body image, such as those brought about by unexpected traumatic injury, place the patient at risk for loss, depression, sexual problems, guilt, and grief.25

It is important to assist the patient with integration of this changed body image into his or her concept of self. Interventions such as facilitating open communication; conveying an empathetic, caring approach; and providing acceptance are useful. It is important to remember that each patient has a personal perception of his or her wounds. A massive abdominal wound that to the nurse is healing well may be of great worry to the patient. He or she may become anxious that the wound will not heal without great scarring or that abdominal organs will be exposed. It is important that the nurse carefully assess the patient’s perceptions of his or her wounds. The patient should be asked whether he or she has any questions about the wound. His or her knowledge about the wound, its care, and the potential for healing should be assessed. The nurse should allow the patient to achieve control by answering only those questions the patient raises. This allows him or her to control the amount of potentially anxiety-producing information received at any one time. Answers to the questions should be conveyed in an accurate, factual, truthful, and reassuring manner. The provision of concrete information helps the patient become focused on reality and reduces uncertainty. The information should be communicated in easy-to-understand language.25

The manner in which friends, family, and staff react to the wound also greatly influences the patient’s sense of self-esteem. Nonverbal body language is a powerful tool, and the health care team must be aware of its unconscious use. If the patient interprets this communication as negative, he or she will experience increased anxiety and self-doubt. In contrast, the patient will be able to begin to positively integrate the wound into his or her body image if he or she senses that the staff conveys a positive and accepting manner when caring for the wound.25

As a response to the mounting anxiety related to the wound and the altered body image, the patient may attempt to cope by putting into play defense mechanisms such as withdrawal, avoidance, and suppression in an attempt to maintain psychologic balance. Dressing changes and wound care are constant reminders of both the changes in the appearance of the body and the traumatic event that produced those changes. It is not unusual for the patient to respond by refusing to cooperate with dressing changes or being noncompliant with wound care. The health care team needs to be sensitive to these issues when caring for the wound, giving the patient choices such as negotiating when the wound care will occur as a strategy to increase his or her sense of control over the situation. Relief from pain is a priority for the patient during dressing changes. Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies should be instituted to manage pain. Adequate relief from anxiety must be provided. Referral to a psychiatric liaison, use of relaxation techniques, and pharmacologic methods should be explored.25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree