Injury rates are high among children and adolescent athletes. Psychosocial stressors, such as personality, history of stressors, and life event stress can influence injury occurrence. After injury, those same factors plus athletic identity, self-esteem, and significant others—such as parents, coaches, and teammates—can affect injury response, recovery and subsequent sport performance. Goal setting, positive self-talk, attribution theory, and relaxation or mental imagery are psychologic interventions that can help injured athletes cope with psychosocial stressors. Medical professionals should be aware of the potential influence that psychosocial stressors and psychologic interventions can have on injury occurrence, injury recovery, and sport performance.

Injury rates are high among children and adolescent athletes. Psychosocial stressors, such as personality, history of stressors, and life event stress can influence injury occurrence. After injury, athletic identity, self-esteem, and significant others—such as parents, coaches, and teammates—can affect injury recovery and sport performance. Goal setting, positive self-talk, attribution theory, and relaxation or mental imagery are psychologic interventions that can help injured athletes cope with psychosocial stressors. Medical professionals should be aware of the potential influence that psychosocial stressors and psychologic interventions can have on injury occurrence, injury recovery, and sport performance.

M.B, a 14 year old white, athletic basketball player suffered severe ankle sprains while attending a parochial school. Before these injuries, M.B. was dealing with his parents’ impending divorce. Although the divorce was stressful, he felt he had a strong support system from his teammates. Moreover, M.B., a high athletic identity player with high self-esteem, had been identified as a promising, talented point guard. Perhaps related to the ankle sprains, the following season he was troubled by severe Achilles tendonitis and was unable to participate a full season. Feeling depressed, frustrated, misunderstood by the coach, alienated from his team, and without any known coping skills other than sport affiliation, M.B. began to hang out with a different peer group. Bored and feeling worthless, he doubted his physicians and physical therapists in terms of their ability to help him get back into sports and into the line up. As a result, he started to sever his connection to basketball. M.B. replaced his athleticism with risk taking in the party scene: substituting the “high” of athletic competition and success with experimental highs from pot, alcohol, and sex. M.B. continued to see his sport psychology counselor, who expressed concern about him giving up on his rehabilitation. He went snowboarding a few times, which did not seem to aggravate his Achilles tendonitis symptoms. In doing so, he gradually felt reconnected with his athleticism. Together, M.B. and the counselor wrote a script for a DVD to be used to warn other adolescents about the psychosocial pitfalls of unresolved sport injury. M.B. embraced this challenge and gradually became a role model, “walking the talk” for more optimal behavior. His self-esteem increased by doing something that would help others. Gradually, educational pursuits became his priority and today he is bilingual, working in international relations in South America. He enjoys recreational activities but respectfully tries to avoid injury.

Participation in organized youth sports has become increasingly popular and widespread over the past several decades. In the United States, 30 to 45 million children and adolescents participate in organized sports each year . Although sport participation promotes an active lifestyle and decreases the risk of childhood obesity, a concern among medical professionals has been the increased pressure for youth to specialize in sports at an early age. Today, it is not uncommon to find young gymnasts and figure skaters training 20-plus hours per week, year round. Similarly, hockey and soccer players as young as 6 years old travel hundreds of miles for competitions. Connected to excessive playing time and overtraining is the increased likelihood of injury.

Injury rates among youth sport participants are high. Sport and exercise related injuries accounted for 65% of emergency department visits surveyed over 1 year for youth under 19 years of age . Although injuries are often minor with respect to time loss , stresses associated with injury may be significant, especially for youth experiencing injury for the first time. While the physical components of injury are usually the focus of treatment, the stress associated with injury and recovery may be minimized and escape detection. Without recognition and, on occasion, intervention, psychosocial stressors may precipitate injury and negatively impact rehabilitation and sport performance upon return to the sport.

For the sake of brevity, this article does not focus on physical factors, such as excessive playing time, overtraining, and burnout that influence injury and rehabilitation. Instead the discussion in this article is on psychosocial factors (eg, athletic identity, body image, sport environment, and other social influences, such as life stress) that may impact children and adolescent athletes before and following injury. The article concludes by discussing psychologic interventions that help alleviate stress and total mood disturbance (TMD) resulting from injury.

Athletic injury prediction models

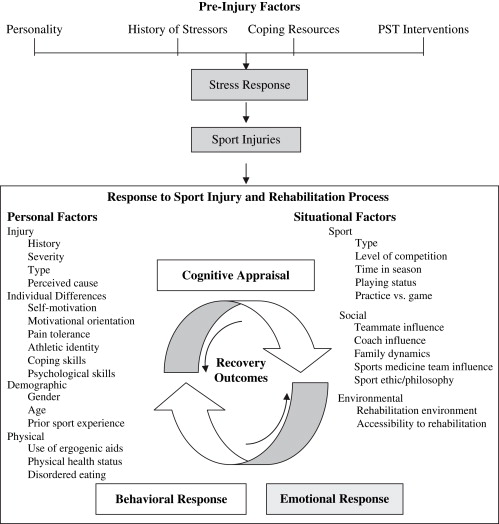

Over the last two decades, two pivotal, empiric sport injury models ( Fig. 1 ) have evolved to investigate psychosocial factors that may influence the risk of obtaining a sport injury and recovery following injury. The Andersen and Williams model (see top portion of Fig. 1 ) provided a framework to examine psychologic precursors, such as personality, history of stressors, and coping resources in relation to sport injury . The main premise of this model is that a psychophysiologic response is elicited if an athlete cognitively appraises a situation (rational or irrational) as stressful, has a history of stressors, has a personality likely to intensify the stress response, and has few coping resources. These variables, alone or in combination, precipitate a stress response . Once a stress response is elicited, physiologic and attentional changes occur (ie, increased muscle tension, narrowing of the visual field, and distractibility), thereby increasing likelihood of injury .

Wiese-Bjornstal and colleagues (see bottom half of Fig. 1 ) expanded the Andersen and Williams stress injury model by examining emotional response and psychologic recovery following injury. In accordance with the Andersen and Williams model, the stress response associated with personality, history of stressors, and coping, which influence athletes before injury, continues to influence athletes after injury. These same factors, along with the stress of being injured, influence the athlete’s ability to cognitively appraise the injury situation. Cognitive appraisal dictates an athlete’s emotional reaction to injury that ultimately determines behavioral responses to injury and rehabilitation . Furthermore, it is hypothesized that an athlete’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral response to injury is influenced by personal and situational factors. Personal factors that may affect recovery from injury include injury history and severity, motivation to recover from injury, mood state, and coping abilities. Gender, prior sport experience, and use of ergogenic aids are additional personal factors that may influence injury recovery. Situational factors that may potentially affect injury recovery include level of competition, time in season, playing status, and influences from teammates, coaches, and sports medicine professionals. While these factors directly affect the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral response, they indirectly affect physical and psychologic recovery from injury.

Although a complete review of the literature is not warranted for this article, these two injury models highlight physical and psychosocial stressors that may affect injury rates, in addition to injury recovery and after-injury sport performance. Only research on psychosocial stressors relevant to the child, adolescent, and young adulthood populations are thoroughly reviewed in this article.

Psychologic stressors before injury

As postulated by Andersen and Williams (see top portion of Fig. 1 ) , history of stressors (ie, life event stress, daily hassles, and previous injury history), personality characteristics (ie, hardiness, locus of control, and competitive trait anxiety), and coping resources (ie, general coping behaviors, social support, stress management, and psychologic skills training) directly elicit a stress response, while indirectly influencing injury occurrence. Early research in this domain focused on the unidimensional relationships of life event stress, competitive trait anxiety, and social support to injury occurrence. Although all these psychologic variables positively relate to injury occurrence , life event stress has been the most compelling. Of 35 studies reviewed, 30 related life event stress to sport injury . Furthermore, athletes with high life stress were two to five times more likely to sustain athletic injury . When analyzed by negative and positive life stress, negatively appraised life events were significantly more likely to predict sport injury occurrence . Despite empiric evidence that unidimensional relationships exist between personality, coping resources, and history of stressors to injury, little was known about the moderating effects these variables would have on the life event stress-injury relationship .

Petrie examined collegiate female gymnasts and reported that high negative life event stress accounted for 14% to 24% of the injury variance for gymnasts with low levels of social support. No significant life event stress-injury relationship was found among gymnasts with high social support. Smith and colleagues found negative life event stress accounted for 22% to 30% of the injury variance when athletes reported a combination of high stress and low social support and coping ability. Athletes with high social support or high coping resources did not elicit a negative life event-stress injury relationship.

Maddison and Prapavessis studied rugby players (16–34 years of age). Social support, coping resources, competitive trait anxiety, and history of stressors to injury occurrence were examined. Negative life event stress accounted for 31% of the injury variance for rugby players who used avoidance-focused coping behaviors (eg, denial and wishful thinking), who reported having inadequate social support, and had a history of previous injuries. Competitive trait anxiety was not significant. Finally, Rogers and Landers examined the influence of negative life event stress, social support, and coping on sport injury occurrence. A secondary purpose was to examine the role of peripheral narrowing on the life event stress-injury relationship for adolescent soccer players. Negative life event stress and poor coping skills significantly contributed to injury occurrence. Simultaneously, high coping skills buffered the negative life event stress-injury relationship. Peripheral narrowing, influenced by life event stress, increased the likelihood of injury occurrence.

These results support the Anderson and Williams empiric model, indicating that psychologic factors may directly elicit a stress response and indirectly increase the risk of injury for young athletes. Medical professionals should be aware of the influence negative life events have on injury occurrence and be able to help young athletes cope with these events. Given the empiric support for psychologic skill training intervention effect on reducing injury vulnerability , medical professionals should provide social support, if need be, and teach young athletes skills that will equip them to cope with life event stress. The psychologic interventions section at the end of this article provides specific information on helping athletes cope with psychosocial stressors.

Psychologic stressors before injury

As postulated by Andersen and Williams (see top portion of Fig. 1 ) , history of stressors (ie, life event stress, daily hassles, and previous injury history), personality characteristics (ie, hardiness, locus of control, and competitive trait anxiety), and coping resources (ie, general coping behaviors, social support, stress management, and psychologic skills training) directly elicit a stress response, while indirectly influencing injury occurrence. Early research in this domain focused on the unidimensional relationships of life event stress, competitive trait anxiety, and social support to injury occurrence. Although all these psychologic variables positively relate to injury occurrence , life event stress has been the most compelling. Of 35 studies reviewed, 30 related life event stress to sport injury . Furthermore, athletes with high life stress were two to five times more likely to sustain athletic injury . When analyzed by negative and positive life stress, negatively appraised life events were significantly more likely to predict sport injury occurrence . Despite empiric evidence that unidimensional relationships exist between personality, coping resources, and history of stressors to injury, little was known about the moderating effects these variables would have on the life event stress-injury relationship .

Petrie examined collegiate female gymnasts and reported that high negative life event stress accounted for 14% to 24% of the injury variance for gymnasts with low levels of social support. No significant life event stress-injury relationship was found among gymnasts with high social support. Smith and colleagues found negative life event stress accounted for 22% to 30% of the injury variance when athletes reported a combination of high stress and low social support and coping ability. Athletes with high social support or high coping resources did not elicit a negative life event-stress injury relationship.

Maddison and Prapavessis studied rugby players (16–34 years of age). Social support, coping resources, competitive trait anxiety, and history of stressors to injury occurrence were examined. Negative life event stress accounted for 31% of the injury variance for rugby players who used avoidance-focused coping behaviors (eg, denial and wishful thinking), who reported having inadequate social support, and had a history of previous injuries. Competitive trait anxiety was not significant. Finally, Rogers and Landers examined the influence of negative life event stress, social support, and coping on sport injury occurrence. A secondary purpose was to examine the role of peripheral narrowing on the life event stress-injury relationship for adolescent soccer players. Negative life event stress and poor coping skills significantly contributed to injury occurrence. Simultaneously, high coping skills buffered the negative life event stress-injury relationship. Peripheral narrowing, influenced by life event stress, increased the likelihood of injury occurrence.

These results support the Anderson and Williams empiric model, indicating that psychologic factors may directly elicit a stress response and indirectly increase the risk of injury for young athletes. Medical professionals should be aware of the influence negative life events have on injury occurrence and be able to help young athletes cope with these events. Given the empiric support for psychologic skill training intervention effect on reducing injury vulnerability , medical professionals should provide social support, if need be, and teach young athletes skills that will equip them to cope with life event stress. The psychologic interventions section at the end of this article provides specific information on helping athletes cope with psychosocial stressors.

Psychologic stressors following injury

Athletic identity, self-esteem, total mood disturbance

Athletic identity refers to “the degree to which an individual identifies with their athletic role” . Athletes with high athletic identity identify primarily with sport, whereas athletes with a low athletic identity tend to participate in multiple activities, with sport being one of many activities. One benefit of strongly identifying with the athletic role is an increase in self-esteem. For older children and adolescents, high self-esteem helps mediate the continuous physical, psychologic, and social changes that occur during this developmental period . Participation in sport correlates positively with high self-esteem scores , particularly in the esteem domains of physical appearance and physical competency . Ironically, this same athletic identification that serves to protect self-esteem before injury is a risk factor for diminished feelings of self worth and increased mood disturbance after injury.

Sonestrom and Morgan were the first to examine the impact of injury on a multidimensional measure of self-esteem. Results revealed a post-injury decrease in the physical self-efficacy and perceived physical competency dimensions of self-esteem. These results support the notion that components of self-esteem that protect self-worth before injury also serve to decrease it following an injury. Furthermore, the majority of studies that examined before- and after-injury changes, using a unidimensional measure of self-esteem, found diminished self-esteem after injury . McGowan and colleagues conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with injured collegiate football players to examine the reasoning for decreased self-worth after injury. Themes that emerged related to the isolation players felt from their team and the fact that the team was continuing to win without them. These results reveal athletes who sustain an injury also show significant changes to self-esteem after injury. Coupled with diminished self-esteem is an increased risk for total mood disturbance.

Brewer conducted a series of four studies examining the relationship between an athlete’s identification with the athlete role to after-injury depression for real and imagined injuries. Results supported his hypothesis that collegiate athletes who identified highly with the athletic role were more likely to respond to an injury with depression. Similarly, adolescent athletes who had a high athletic identity also responded with high depressive symptoms . Moreover, Smith and colleagues studied before- and after-injury mood state and self-esteem changes among competitive high school and collegiate athletes. Results indicated a statistically significant change in total mood disturbance before and after injury. Specifically, before injury the athletes exhibited a positive mental health profile: low levels of depression, anger, confusion, and fatigue, and high levels of vigor. Following injury, the mental health profile reversed, showing high levels of depression and anger, and low levels of vigor. When examined further, the increase in depression was significantly related to the severity of the injury. This finding supported an earlier study conducted by Smith and colleagues , in which severity of injury was a significant predictor of depression in injured, recreational athletes.

For most athletes, the increased TMD lasts approximately 1 month , with negative mood disturbance occurring immediately following injury and subsiding as the athlete perceives recovery to be occurring . However, for some athletes TMD may not return to before-injury states. Mood disturbance is a concern for adolescent and young adults who are already at approximately three times greater risk for suicide than the general population .

Smith and Milliner reported on five case studies in which injured athletes attempted suicide. Common risk factors associated with the attempted suicides included: (1) an injury that required surgery; (2) a long, demanding rehabilitation that prevented athletes from participating in their sport for at least 6 months; (3) a decrease in athletic skills as a result of the injury; (4) little confidence in their ability to perform at before-injury levels following rehabilitation; (5) replacement by a teammate; and (6) experience of substantial success in their sport before the injury.

These case studies highlight the relevancy of research that suggests young athletes who identify highly with a sport and who sustain an injury have an increased risk for diminished self-worth and increased mood disturbance after injury. Most athletes take injury “in stride” . However, some feel so devalued after an injury that depression may reach clinical levels and thoughts of and attempts at taking one’s life may occur. During patient assessment, medical professionals should be aware of young athletes’ psychologic responses after injury and during the rehabilitation process. Changes in affect, energy, sleep patterns, eye contact, commitment to rehabilitation, and hygiene may be flags for concern. Refer injured athletes to a sport psychologist for counseling for mild to moderate depression and to a sport psychiatrist if depression seems profound (eg, thoughts of suicide, identification of a plan, and acknowledgment of having obtained the means to carry out the plan). Admission for observation and treatment may be indicated.

Body image and eating disorders

Although a review of disordered eating patterns among children and adolescents can be found elsewhere in this issue, this article discusses the impact athletic injury has on the development of eating disorders which can occur in both genders. Young female athletes often have dual, contradicting pressures from society and their athletic participation to satisfy the status quo of an ideal body physique. In Western society, adolescents experience pressure to be thin and have a low body weight. In athletics, female athletes must be strong and muscular, a perception by many that sport is generally associated with masculinity . To offset this perception of masculinity and to conform to the perception of having an ideal body physique, female athletes may resort to unhealthy eating behaviors, such as binging, purging, prolonged fasting, and the use of diuretics, laxatives, and diet pills. Disordered eating and intensive training often leads to the development of the female athlete triad: eating disorder, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis .

Each of the three disorders can alone or in combination have short and long-term health consequences. Risk increases for musculosketal injuries, such as stress fractures and premature osteoporosis because of a loss in bone mineral density . Athletic injury is one possible explanation for the development of one or a combination of all three triad disorders. Sundgot-Borgen studied trigger factors for the development of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia athletica among elite female Norwegian athletes between the ages of 12 and 35 years. Injury was one of several factors that triggered an eating disorder. The anxiety associated with restriction of physical activity, in combination with the contradictory standards about the ideal body physique , performing in aesthetic sports where leanness is a priority, and the pressure placed on athletes by coaches to conform to strict diet plans may place injured athletes at increased risk for an eating disorder. Although more research is needed to verify the role athletic injuries have on the development of one or more of the female athlete triad disorders, medical professionals should watch for signs that the athletic injury may be precipitating an eating disorder. If warranted, the injured athlete should be promptly referred to a comprehensive eating disorder team .

Use of ergogenic aids

A serious injury may result in the need for surgery, time away from sports and the team, rehabilitation, an actual or perceived loss of fitness and athletic skill, and a loss in confidence, as well as the possibility of being replaced on the team . Consequently, injured athletes may be tempted to hurry the healing process by using performance enhancing substances, such as steroids, supplements, prescription drugs, or other substances such as stimulants. Initiating a medical program (even though it is a form of drug abuse) may either actually or be perceived to boost performance.

At present, determining the prevalence of drug use in sport and exercise by adolescents is difficult to accurately assess. Detection requires self-reporting or drug testing. Self-reporting is confounded by validity issues. Validity depends on the honesty of a young athlete who would prefer his or her use not be known. Drug testing is expensive and limited by the sophistication of designer steroids, human growth hormones, and masking agents to help athletes escape detection.

To provide a framework to understand drug abuse, Strelan and Boeckmann adapted a deterrence theory, used to assess the likelihood of compliance with the law, to a model for understanding performance-enhancing drug use in elite athletes. This theory is based on the relationship between deterrents or costs versus benefits. For example, deterrents (costs), such as suspensions, disapproval, guilt, reduced self-esteem and health concerns are weighed against benefits, such as prize money, scholarships, acknowledgment, and achievements. Both deterrents and benefits are moderated by sport related situational factors (eg, level of the athlete’s participation, type and reputation of the drug, and perceived competitiveness). Because elite athletes serve as powerful role models for younger athletes, it is likely that similar processes occur in aspiring adolescents. Adolescent injured athletes are often vulnerable, depressed, deconditioned, and unable to participate in sports, as discussed earlier. The signed preseason contract stating that the young athlete would not use alcohol or drugs during the athletic season has become a moot point and substance abuse may seem like the only way back . Physicians and other health care professionals, in prescribing responsibly, may help prevent substance abuse in injured athletes.

According to the Office of National Drug Control Policy, physicians were the source for 18.3% of narcotics being used by teenagers. The remaining adolescents obtained prescription pain medications from parents, peers, or relatives, perhaps by stealing them from medicine cabinets (10.2%) . Because surgical procedures in adolescents may occur more often for sport-related injuries than for other medical problems, becoming a major source of prescription drugs is a concern for sports medicine practitioners. In addition to health care professionals, other sources include the Internet and workout gyms.

The use of performance enhancing drugs or the abuse of prescription drugs is illegal, immoral, and dangerous. Furthermore, it usually escalates, is expensive, and most often has a negative effect on the athlete’s health . Unfortunately, the solution to the problem is as difficult and multifaceted as the problem itself.

Concluding comments

As postulated by Wiese-Bjornstal and colleagues , when young athletes become injured, personal stressors can affect how they respond and how quickly they recover following an injury. For example, when identity and self-worth is completely accounted for by sport, injury may result in athletes asking: “If I’m not an athlete, then who am I?” This identity crisis negatively affects feelings of self-worth and contributes to TMD. For some athletes, the feelings associated with not being able to participate in sport and exercise may result in risk taking behaviors, including unhealthy eating patterns, suicidal ideations, and drug use to substitute for the athletic “high.” For other athletes, dealing with the physical pain of injury is easier to cope with than dealing with the emotional pain of isolation and depression. For some of these athletes, continuing to train and compete through injury may be perceived as their only viable option; thus, they may return to sport prematurely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree