Childhood obesity is a key public health issue in the United States and around the globe in developed and developing countries. Obese children are at increased risk of acute medical illnesses and chronic diseases—in particular, osteoarthritis, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease, which can lead to poor quality of life; increased personal and financial burden to individuals, families, and society; and shortened lifespan. Physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyle are associated with being overweight in children and adults. Thus it is imperative to consider exercise and physical activity as a means to prevent and combat the childhood obesity epidemic. Familiarity with definitions of weight status in children and health outcomes like metabolic syndrome is crucial in understanding the literature on childhood obesity. Exercise and physical activity play a role in weight from the prenatal through adolescent time frame. A child’s family and community impact access to adequate physical activity, and further study of these upstream issues is warranted. Recommended levels of physical activity for childhood obesity prevention are being developed.

Childhood obesity is a key public health issue in the United States and has been referred to as a global epidemic and public health crisis . Obese children are at increased risk of acute medical illnesses, including asthma and high blood pressure, and chronic diseases—in particular, osteoarthritis, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease . Physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyle are associated with being overweight in children and adults. Thus it is imperative to consider exercise and physical activity as a means to prevent and combat the childhood obesity epidemic.

Definitions

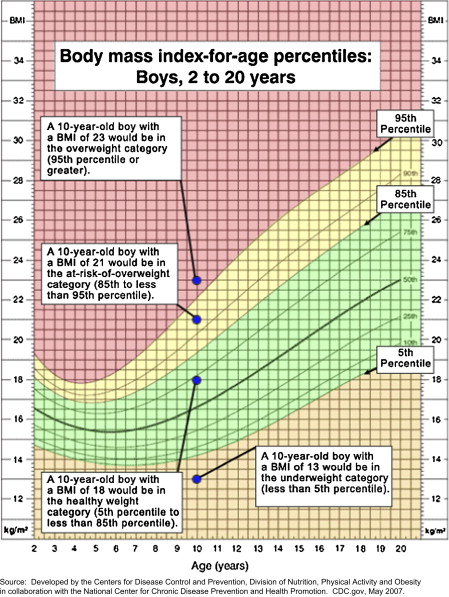

Obesity and overweight are defined in terms of body mass index (BMI). BMI is used to define categories of weight status as it relates to health. BMI is a value derived by using height and weight measurements (weight in kg/height in m 2 ) that gives a general indication of whether weight falls within a healthy range. For adults, BMI strongly correlates with total body fat content as it describes weight relative to height. For children, BMI-for-age is an important concept as children’s body fat changes over the years as they grow ( Fig. 1 ). In addition, boys and girls differ in body fatness as they mature. The National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention use the terms underweight , normal weight , overweight , and obese in adults according to cut-points in BMI and related to BMI-for-age in children, rather than the traditional height/weight charts ( Table 1 ) . For children, underweight is defined as BMI at or below 5th percentile of the sex-specific BMI-for-age growth chart. At risk for overweight is defined as BMI at or above 85th percentile of the sex-specific BMI-for-age growth chart. Overweight is defined as BMI at or above 95th percentile of the sex-specific BMI-for-age growth chart ( Fig. 2 ). Across many studies, childhood obesity was defined as BMI at or above 85th percentile for age and sex.

| Weight status category | Percentile range |

|---|---|

| Underweight | Less than the 5 th percentile |

| Healthy weight | 5 th to less than the 85 th percentile |

| At risk of overweight | 85 th to less than the 95 th percentile |

| Overweight | Equal to or greater than the 95 th percentile |

A recent meta-analysis reported rising numbers of overweight and obese adults and overweight children over the last four decades . A large epidemiologic study, part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), demonstrated that the numbers of overweight children are on the rise . NHANES measured height and weight in more than 4000 adults and 4000 children from 1999 to 2000 and then again from 2001 to 2002. Among children 6 through 19 years of age from 1999 to 2002, 31% were at risk for overweight or overweight and 16% were overweight. Both the meta-analysis and NHANES results indicate continuing disparities in the burden of overweight and obesity by sex and between racial/ethnic groups and related to socioeconomic status.

The metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions that often occur together, including obesity, high blood pressure, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia . These clinical measures assess the cardiovascular disease risk profile of the individual. Metabolic syndrome is a clinical outcome of being overweight or obese that goes beyond measuring BMI only. Metabolic syndrome allows for assessment of the negative health consequences of being overweight and obese. Components of the metabolic syndrome have been studied in children and adolescents related to birth weight, indicating that the intrauterine environment already plays a role in childhood weight status and health outcomes .

Weight status is highly dependent on energy consumed versus energy burned or expended. Physical activity is one of the modifiable components of total energy expenditure, which also includes gender, age, current body weight, basal metabolic rate and, in childhood, the energy cost of growth . The energy cost of growth has two components: (1) the energy needed to synthesize growing tissues and (2) the energy deposited in those tissues. The energy cost of growth is about 35% of total energy requirement during the first 3 months of age, falls rapidly to about 5% at 12 months and about 3% in the second year, remains at 1% to 2% until mid-adolescence, and is negligible in the late teens.

Physical activity not only plays a significant role in expending energy, but also directly impacts physiologic parameters related to weight gain, mainly via fat and glucose metabolism . Skeletal muscle plays a major role in the daily fat oxidation in the body. Physical activity controls fat mass by increasing the amount of fat oxidized at the skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle also serves as an active reservoir of glucose, and regular physical activity promotes insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis independently of its effect on body fat. Exercise also plays a direct role in improving heath outcomes, such as reducing one’s risk of cardiovascular disease.

Prenatal factors

Exercise in pregnancy has been shown to play an important role in preventing chronic health conditions in women . Of interest to this review, exercise in pregnancy was also shown to be beneficial to the growing fetus. Although it is known that women with diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), or obesity tend to have larger babies , the benefits of exercise to normalize infant birth weight are not as widely considered. Women who are the most physically active have the lowest prevalence of GDM, and prevention of GDM may decrease the incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes in both mother and offspring .

Macrosomia leads not only to increase cesarean section and shoulder dystocia rate , but also to negative health outcomes to the child. A longitudinal cohort study in the United States compared children 6 to 11 years old who were large-for-gestational-age versus appropriate-for-gestational-age at birth . Clinical outcomes measured in the study included the metabolic syndrome—obesity (BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance. They found that children exposed to maternal obesity were at increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome, which suggests that obese mothers who do not fulfill the clinical criteria for GDM may still have metabolic factors that affect fetal growth and postnatal outcomes. A retrospective chart review of a multi-ethnic, low-income cohort of children demonstrated that maternal obesity in early pregnancy more than doubled the risk of obesity at 2 to 4 years of age . The researcher concluded that in developing strategies to prevent obesity in preschoolers, special attention should be given to newborns with obese mothers. Chinese researchers evaluated the relationship between birth weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in children and adolescents in more than 80,000 children . High birth weight was correlated with childhood obesity and diabetes. Low birth weight was also associated with childhood diabetes. The researchers concluded that a different relationship existed between the high- and low-birth weight children and the development of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes in childhood. These studies strongly suggest that the long-term health trajectory of the individual vis-à-vis obesity is partially impacted by the fetal environment.

Prenatal factors

Exercise in pregnancy has been shown to play an important role in preventing chronic health conditions in women . Of interest to this review, exercise in pregnancy was also shown to be beneficial to the growing fetus. Although it is known that women with diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), or obesity tend to have larger babies , the benefits of exercise to normalize infant birth weight are not as widely considered. Women who are the most physically active have the lowest prevalence of GDM, and prevention of GDM may decrease the incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes in both mother and offspring .

Macrosomia leads not only to increase cesarean section and shoulder dystocia rate , but also to negative health outcomes to the child. A longitudinal cohort study in the United States compared children 6 to 11 years old who were large-for-gestational-age versus appropriate-for-gestational-age at birth . Clinical outcomes measured in the study included the metabolic syndrome—obesity (BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance. They found that children exposed to maternal obesity were at increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome, which suggests that obese mothers who do not fulfill the clinical criteria for GDM may still have metabolic factors that affect fetal growth and postnatal outcomes. A retrospective chart review of a multi-ethnic, low-income cohort of children demonstrated that maternal obesity in early pregnancy more than doubled the risk of obesity at 2 to 4 years of age . The researcher concluded that in developing strategies to prevent obesity in preschoolers, special attention should be given to newborns with obese mothers. Chinese researchers evaluated the relationship between birth weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in children and adolescents in more than 80,000 children . High birth weight was correlated with childhood obesity and diabetes. Low birth weight was also associated with childhood diabetes. The researchers concluded that a different relationship existed between the high- and low-birth weight children and the development of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes in childhood. These studies strongly suggest that the long-term health trajectory of the individual vis-à-vis obesity is partially impacted by the fetal environment.

Antepartum issues: infancy and preschool years

Physical activity has not been studied in early infancy as a means of preventing childhood obesity. Rather, nutrition—breast-feeding in particular—has been studied most related to infant weight. For instance, one study correlated rapid infant weight gain from birth to 6 months with childhood overweight at 4 years of age . There is a natural phenomenon of increasing adiposity during the first year of life, then a decrease until a second rise in adiposity at about 5 to 6 years old. The term adiposity rebound has been given to the phenomenon of this second increase in adiposity ( Fig. 3 ) . Studies have shown a relationship between the age at adiposity rebound and final adult adiposity. An early rebound (before 5.5 years of age) was followed by a significantly higher adiposity level than a later rebound (after 7 years of age) in one study , whereas a second study showed that adiposity rebound before ages 4 to 6 was associated with obesity in adulthood . The preschool years are thought to be a critical period for obesity prevention as indicated by the association of the adiposity rebound and obesity in later years; however, there is limited research addressing the role of exercise and physical activity in obesity prevention in preschool aged children .