The ultimate goal of any medical treatment is to improve, or at least maintain, the overall health and function of the patient. On a purely technical level, fracture care aims to restore anatomy and alignment to prevent deformity and disability. Traditionally, the success of orthopaedic fracture care has been based on clinical and radiographic evaluation utilizing objective measures, such as range of motion, strength, alignment, and fracture union; however, satisfactory clinical and radiographic results do not always translate into patient satisfaction and restoration of function. Recognition of this potential disparity has led to the current emphasis on patient-oriented outcome measures. In conjunction with general health status, factors that are important to the patient—comfort, ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL), social well-being, work ability, and quality of life—impact directly on the patient’s functional recovery and form the basis for outcomes assessment; therefore, the success or failure of a treatment should be based on both measures of objective clinical evaluation and subjective patient assessment. Daum et al1 has described outcomes research as one of the three elements of quality health care, which also includes the utilization of practice guidelines and necessitates continuous quality improvement. Efficacy indicates whether a treatment or procedure works, and is usually investigated in a specific setting by select individuals.2 Effectiveness, on the other hand, indicates whether an efficacious treatment or procedure works when utilized by the general population. Outcomes research seeks to determine the effectiveness of treatments in terms of both objective clinical measures and patient-oriented outcomes. A treatment that is efficacious in a controlled setting may prove to be ineffective when used in the general population. Ideal treatments would always lead to optimal outcomes. Treatments that fall short of these optimal outcomes are identified by outcomes research, thereby allowing revision of treatments to improve the overall quality of health care. Outcomes research is composed of several different methods. Large databases can be analyzed retrospectively to perform epidemiologic studies and limited outcomes analyses. An example is the currently available Medicare database, which provides information on mortality, length of hospital stay, complications, and reoperations.3 Because these are claims data, however, they are subject to errors in diagnoses and procedures, and do not reflect changes in patient’s comfort, function, and health status.3,4 Other limitations include lack of information on severity of disease, difficulty differentiating between preexisting disease and complications, and lack of patient-based outcomes. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) attempted to establish an important initiative in the development of outcomes research by developing a national musculoskeletal database called the Musculoskeletal Outcomes Data Evaluation and Management System (MODEMS) Program, which consisted of the Lower Limb Instrument, the Spine Instrument, the Pediatrics Instrument, and an upper extremity instrument, which was called the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) Instrument. The goal was to use the database to present national statistics on outcomes data, allow comparison between individual practices, and help establish standards for treatment.5 Unfortunately, widespread use was never realized, and the project has been discontinued. A major event in the development of outcomes research was Wennberg and Gittelsohn’s6 demonstration of the wide variation in rates of surgical procedures from one geographic region to another. The method of small-area analysis they developed allowed the calculation of per capita rates of medical and surgical procedures for patients at different hospitals serving different regions.7 Within orthopaedics, although hip fracture and polytrauma have low variation, almost every other condition or procedure has considerable variation of hospital and surgical use rates.8 Variation in health care utilization may signify uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of treatments and surgical indications. An unusually low rate would indicate that patients in that region are underserved, whereas an unusually high rate would indicate that patients are receiving excessive medical care. One of the aims of outcomes research is to determine the appropriate rate for different treatments. Vitale et al9 investigated the state-to-state variation in rates for total shoulder arthroplasty, humeral head replacement, and rotator cuff repair. The rates for these procedures varied from state to state by as much as tenfold. Humeral head replacement showed the least variation of the three procedures. All three procedures were performed less often in states that are more densely populated. No consistent, significant relationship was found between the population density of orthopaedic surgeons and shoulder specialists and the rates of any procedure. Meta-analysis utilizes literature review by combining data from multiple studies to create a larger, more statistically significant pool of data for analysis. To be included, the studies must conform to a rigorous protocol with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to minimize publication and detection bias. Ideally, only prospective, randomized clinical trials would be included in the analysis; however, because few orthopaedic studies have adhered to this study design, the criteria may be broadened to include other types of studies. In orthopaedics, meta-analyses have been published for such conditions as hip fracture and lumbar spine fusion.10,11 An attempted meta-analysis of treatment outcomes for three-and four-part proximal humerus fractures by Misra et al12 concluded that the data from the orthopaedic literature are inadequate for evidence-based decision making mainly due to the lack of randomized controlled trials and uniformity of reporting outcomes. Nevertheless, based on the literature available, they found that nonoperatively treated patients showed inferior results with regard to pain relief and range of motion compared with operatively treated patients. Pain relief and range of motion showed no difference between patients treated with hemiarthroplasty and patients treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). In 2002 the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Injuries Group completed a systematic review of the literature in an attempt to determine the appropriate treatments for proximal humerus fractures.13 The group was able to find only 10 studies that met the inclusion criteria of randomized or quasi-randomized (not strict randomization, e.g., allocation of treatment based on hospital record number) studies.14–23 The group concluded that there is insufficient evidence from randomized trials to determine which interventions are the most appropriate for the different types of proximal humerus fractures. The available data do not confirm that surgery leads to better outcomes for three-and four-part fractures. The group’s conclusion stressed the need for future randomized controlled trials to define more clearly the role and most effective type of surgical intervention in the management of proximal humerus fractures. Clinical research studies are the cornerstone of outcomes research. Prospective studies that allow the investigator to determine which outcomes to observe and record in a standardized fashion are preferred over retrospective studies, which rely on patients’ memory and review of medical records that were not specifically set up for the purpose of the study. A control or alternative treatment group enhances the validity of the study and allows for direct comparisons of interventions. The ideal study design is the prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial. Unfortunately, few orthopaedic studies have adhered strictly to these recommendations.2,3,5,13 Whatever the study design, the end results being studied need to be clearly defined. In orthopaedic clinical research, these end results should include both objective clinical measures and patient-oriented outcomes, including physical, psychological, and social function as well as quality of life and patient satisfaction. Much of the emphasis for the development of outcomes research grew from government policy makers’ reaction to the rapidly rising cost of health care. In addition to determining the effectiveness of a treatment or procedure, outcomes research seeks to determine the effectiveness as a function of the financial cost; that is, the cost-effectiveness. Because of the limited resources in health care, cost-effectiveness analysis adds a new dimension to the goal of determining the best overall treatment for a particular disease. Emphasis has been placed on the design of outcomes instruments that accurately determine objective clinical and patient-oriented outcomes after treatments. These self-assessment questionnaires assess treatment effectiveness from the perspective of the patient. To be clinically useful, the outcomes instrument must be valid, reproducible or reliable, internally consistent, and responsive to change. Validity refers to whether the instrument measures what it is supposed to measure, and consists of content validity, criterion validity, and construct validity1,5 (Table 1-1). Reproducibility refers to the ability of the instrument to yield the same result both on separate occasions and when rated by different observers; that is, the test-retest reliability and interobserver reliability. Internal consistency means that the instrument is able to measure a single outcome correctly, independent of other variables. Responsiveness to change indicates that the instrument is sensitive to clinically important changes.

Principles of Treatment and Outcomes Assessment

Outcomes Research

Outcomes Research

Outcomes Instruments

Outcomes Instruments

| Content validity: The comprehensiveness of the items on an outcomes instrument and the extent to which the items meet the aims of the instrument. Can be assessed by patient and clinician review. |

| Criterion validity: Whether the outcomes instrument correlates with the “gold standard” measure or with established objective tests and clinical evaluations. |

| Construct validity: Used when there is no “gold standard” measure for comparison. Assessed by comparison with already validated outcomes instruments. |

There are two types of outcomes instruments: (1) instruments that are specific to a particular disease or region of the body, and (2) general health status instruments. Region-specific instruments, such as those for the shoulder, disease-specific instruments, such as those for glenohumeral arthritis, and general health status instruments do not always demonstrate equal responsiveness to change for all aspects of a particular disability or disease. Because they potentially convey different information, both types of instruments are needed in the complete evaluation of a disability or disease.24

Outcomes Instruments in Proximal Humerus Fractures

Outcomes Instruments in Proximal Humerus Fractures

Many studies of outcomes in proximal humerus fractures use shoulder scoring instruments that were originally developed in the context of surgery for various other shoulder pathologies, such as degenerative joint disease and rotator cuff tears. Only later were these instruments adopted for general use in the evaluation of shoulder problems. To varying degrees, all shoulder outcomes instruments assess pain, function, range of motion, and strength. The main problem with these instruments is that each one emphasizes a different aspect of the shoulder evaluation. Some instruments emphasize pain, whereas others place more emphasis on function, and still others emphasize range of motion. Because of these differences, comparing the instruments becomes difficult if not impossible, and no individual instrument has become universally accepted. To date, an outcomes instrument specifically designed to evaluate proximal humerus fractures has not been developed.

Neer’s Shoulder Grading Scale

Originally developed to assess shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral degenerative joint disease, the Neer grading scale has been used widely to assess outcome following proximal humerus fracture (Table 1-2).25 In the 100-point system, 35 points are for pain, 25 points for range of motion (flexion, extension, abduction, internal and external rotation), 30 points for function (10 activities including strength, reaching, and stability), and 10 points for reconstruction of the anatomy based on radiographic appearance. Neer considered pain relief to be the most important consideration, and functional recovery secondary. A final question asks if the patient feels better, the same, or worse after surgery. An excellent result is 90 points or more; satisfactory, 80 to 89; unsatisfactory, 70 to 79; and failure, less than 70. Unlike other assessment tools, the Neer grading scale incorporates radiographic findings into the evaluation. It takes only a few minutes to complete and has been used widely in both Europe and the United States. Most reports on outcomes of proximal humerus fractures using the Neer grading scale have adhered to this original scoring system because of the opportunity the system offers to quantify results on a 0- to 100-point scale.26–40 Nonetheless, the grading system was modified by Neer et al41 and Cofield42 in the scoring of pain and strength, each on a 0 to 5 scale, and assessment of range of motion, which focused on active elevation, external rotation, and internal rotation. The modified Neer system considers an outcome excellent if the patient has slight or no pain, is satisfied with the treatment, and has at least 140° of active elevation and at least 45° of external rotation.43 The outcome is considered satisfactory if the patient has no, slight, or moderate pain with strenuous activity only; is satisfied with treatment; and has at least 90° of elevation and at least 20° of external rotation. The outcome is considered unsatisfactory if any of these criteria are not met or if the patient undergoes an additional operative procedure. Although the modified Neer system continues to stratify outcomes according to excellent, satisfactory, and unsatisfactory results, it no longer assigns point values to the overall outcome.

| Points | |

|---|---|

| Pain | 35 |

| Function Strength | 10 |

| Reaching | 2 |

| Top of head | |

| Mouth | 2 |

| Belt buckle | 2 |

| Opposite axilla | 2 |

| Brassiere hook | 2 |

| Stability | |

| Lifting, throwing, pounding, pushing, hold overhead | 10 |

| Range of motion | |

| Flexion | 6 |

| Extension | 3 |

| Abduction (coronal plane) | 6 |

| External rotation | 5 |

| Internal rotation | 5 |

| Radiograph | 10 |

| Maximum score | 100 |

| Patient satisfaction with outcome | Yes/No |

Data from Neer CS II. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:1077–1089.

American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment and Shoulder Score Index

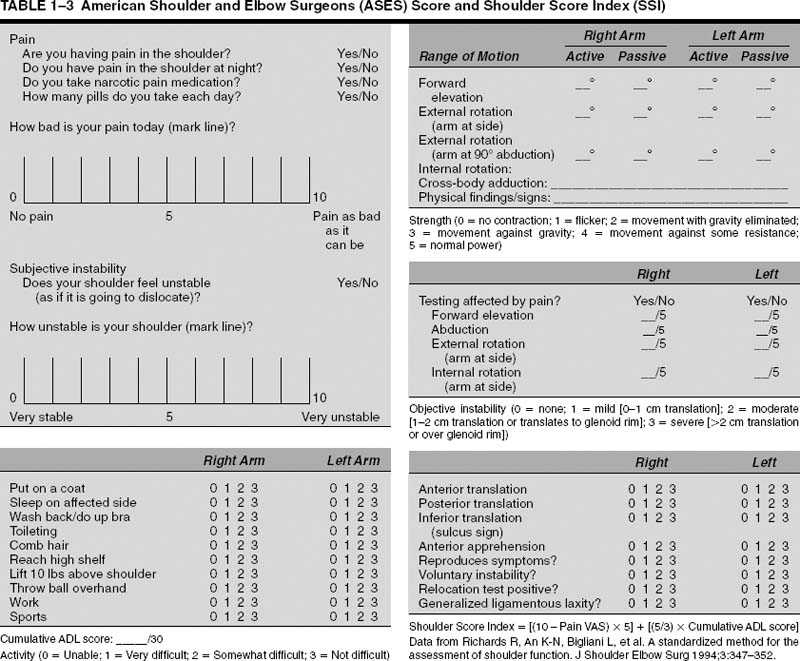

The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) adopted the ASES Standardized Shoulder Assessment in an attempt to create a universal method for evaluating shoulder function (Table 1-3).44 The ASES assessment is composed of a patient self-evaluation section and a physician assessment section. The patient self-evaluation contains 10-point visual analogue scales (VASs) for pain and instability and a 10-item questionnaire to assess ADL. ADL is evaluated on a 4-point ordinal scale that can be summed to determine a cumulative ADL index. The physician assessment takes about 10 to 15 minutes to complete and evaluates active and passive range of motion, and physical findings such as tenderness and impingement, strength, and stability. The combination of the VAS score for pain (50%) and cumulative ADL index (50%) constitutes the Shoulder Score Index, which can be used for quantitative comparisons between studies. The self-evaluation section has the added benefits of not requiring the presence of a physician and taking only a few minutes to complete. A deficiency of the ASES assessment is that it does not evaluate overall patient satisfaction or subjective improvement with treatment. Experience with the Shoulder Score Index has shown that it may not be as sensitive to some shoulder disorders (instability) as others.45

The Constant Scoring System

The Constant Scoring System46 was designed to be a simple method to evaluate shoulder function and to be sensitive to most shoulder problems (Table 1-4). The subjective section allows 15 points for pain and 20 points for ADLs, whereas the objective section allows 40 points for range of motion and 25 points for strength. The developers of the Constant score have demonstrated its reliability and validated the instrument by comparing normal individuals with symptomatic patients.46 The Constant score decreases with age and varies with gender, so the scores should be age-and sex-adjusted. The assessment takes only a few minutes to complete but requires a spring balance or dynamometer for strength testing, which may not be readily available in many clinical practices. An additional limitation is that the Constant score may be insensitive to shoulder instability.47 It should be noted that 65% of the score is allocated to objective measures, which may diminish the patient-based contribution to the score. Although not utilized as widely in the United States, the Constant Scoring System is used widely in Europe and has been adopted by the European Society for Surgery of the Shoulder and Elbow.

The UCLA Shoulder Rating Scales

The UCLA Shoulder Assessment was created to assess the outcome for total shoulder arthroplasty.48 A modification of this scoring system, the UCLA End-Result Score (UCLA score) was used to evaluate rotator cuff repair (Table 1-5).49 Considered more detailed and easier to use in terms of assessment of range of motion and strength, the UCLA score is more widely accepted and utilized than its earlier version. Out of a possible 35 points, the score includes up to 10 points each for pain and function, and up to 5 points each for range of active forward elevation, strength of forward elevation, and patient satisfaction. This scoring system primarily emphasizes pain and function. The overall score is stratified as excellent (34 to 35 points), good (29 to 33 points), or poor (28 points or less). The UCLA assessment is simple to use, takes only a few minutes to complete, and incorporates patient satisfaction into the evaluation; however, it does not test external and internal rotation range of motion or strength. Patient satisfaction is allotted only 5 of the possible 35 points, which underemphasizes this component of the assessment. Moreover, because the score is based on only 35 points, minor alterations in any of the parameters could disproportionately affect the overall score.

| Points | |

|---|---|

| Pain | |

| None | 15 |

| Mild | 10 |

| Moderate | 5 |

| Severe | 0 |

| Activities of daily living | |

| Activity | |

| Work | Up to 4 points |

| Recreation/sports | Up to 4 points |

| Sleep | Up to 2 points |

| Positioning | |

| Up to waist | 2 |

| Up to xiphoid | 4 |

| Up to neck | 6 |

| Up to top of head | 8 |

| Above head | 0 |

| Active range of motion | |

| Forward elevation | |

| 0–30° | 0 |

| 31–60° | 2 |

| 61–90° | 4 |

| 91–120° | 6 |

| 121–150° | 8 |

| 151–180° | 10 |

| Lateral elevation | |

| 0–30° | 0 |

| 31–60° | 2 |

| 61–90° | 4 |

| 91–120° | 6 |

| 121–150° | 8 |

| 151–180° | 10 |

| External rotation | |

| Hand behind head with | 2 |

| elbow flexed | |

| Hand behind head with | 4 |

| elbow held back | |

| Hand on top of head with | 6 |

| elbow held forward | |

| Hand on top of head with | 8 |

| elbow held back | |

| Full elevation from on top of head | 10 |

| Internal rotation | |

| Dorsum of hand to lateral thigh | 0 |

| Dorsum of hand to buttock | 2 |

| Dorsum of hand to lumbosacral | 4 |

| junction | |

| Dorsum of hand to waist (third lumbar vertebra) | 6 |

| Dorsum of hand to twelfth dorsal vertebra | 8 |

| Dorsum of hand to interscapular region (seventh dorsal vertebra) | 10 |

| Power:——— lbs | 25 |

| Maximum score | 100 |

Data from Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop 1987;214:160–164.

| Points | |

|---|---|

| Pain | |

| Present all of the time and unbearable; strong medication frequently | 1 |

| Present all of the time but bearable; strong medication occasionally | 2 |

| None or little at rest, present during light activities; NSAIDs frequently | 4 |

| Present during heavy or particular activities only; NSAIDs occasionally | 6 |

| Occasional and slight | 8 |

| None | 10 |

| Function | |

| Unable to use limb | 1 |

| Only light activities possible | 2 |

| Able to do light housework or most ADLs | 4 |

| Most housework, shopping, and driving possible; able to do hair and dress and undress, including fastening brassiere | 6 |

| Slight restriction only; able to work above shoulder level | 8 |

| Normal activities | 10 |

| Active forward flexion | |

| 150° or more | 5 |

| 120 to 150° | 4 |

| 90 to 120° | 3 |

| 45 to 90° | 2 |

| 30 to 45° | 1 |

| Less than 30° | 0 |

| Strength of forward flexion (manual muscle-testing) | |

| Grade 5 (normal) | 5 |

| Grade 4 (good) | 4 |

| Grade 3 (fair) | 3 |

| Grade 2 (poor) | 2 |

| Grade 1 (muscle contraction) | 1 |

| Grade 0 (nothing) | 0 |

| Satisfaction of the patient Satisfied and better | 5 |

| Not satisfied and worse | 0 |

| Overall score | ____ (out of 35) |

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Data from Ellman H, Hanker G, Bayer M. Repair of the rotator cuff: end-result study of factors influencing reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68: 1136–1144.

Shoulder Severity Index

The Shoulder Severity Index (SSI), also called the Severity Index for Chronically Painful Shoulders, was developed to assess patients with painful, chronic shoulder disabilities.50 Through mathematical formulas, the SSI allocates 30 points to pain, 40 points to function, 15 points to strength, and 15 points to a VAS for daily handicap. Adjustments are then made for chronically painful shoulders, and for elderly patients with limited activity or prosthetic replacement. The significance of the SSI is that it was one of the first outcomes instruments to evaluate pain in different situations of daily life, and assess function according to specific daily activities. This complicated system has largely been supplanted by simpler instruments.

Simple Shoulder Test

The Simple Shoulder Test (SST) was designed to be a quick and easy shoulder assessment instrument that is sensitive to a wide range of shoulder problems (Table 1-6).4 The SST has proven useful in the assessment of primary glenohumeral degenerative joint disease, and has been used to demonstrate the effectiveness of shoulder arthroplasty in treating this condition.51,52 The SST consists of 12 “yes” or “no” questions derived from common complaints of patients presenting to the University of Washington Shoulder Service with a variety of shoulder problems. The limitations of the SST are that it provides little information on the severity of symptoms, it does not ask about overall patient satisfaction with treatment, and, because there is no scoring system, it makes comparisons among patients and treatments difficult. The creators of the SST advocate its use as a minimal data set of functional information that can be gathered quickly in any type of practice, as well as an efficient means of follow-up for patients who can perform the evaluation by themselves. Additional questions tailored to the individual patient may then be asked by the clinician.

| (Answer “Yes” or “No” to each) |

|---|

| 1. Is your shoulder comfortable with your arm at rest by your side? |

| 2. Does your shoulder allow you to sleep comfortably? |

| 3. Can you reach the small of your back to tuck in your shirt with your hand? |

| 4. Can you place your hand behind your head with the elbow straight out to the side? |

| 5. Can you place a coin on a shelf at the level of your shoulder without bending your elbow? |

| 6. Can you lift 1 pound (say, a full pint container) to the level of your shoulder without bending your elbow? |

| 7. Can you lift 8 pounds (say, a full gallon container) to the level of the top of your head without bending your elbow? |

| 8. Can you carry 20 pounds (say, a bag of potatoes) at your side with the affected extremity? |

| 9. Can you toss a softball underhand 10 yards or more with the affected extremity? |

| 10. Can you throw a softball overhand 20 yards or more with the affected extremity? |

| 11. Can you wash the back of your opposite shoulder with the affected extremity? |

| 12. Would your shoulder allow you to work full-time at your regular job? |

Data from Matsen F III, Smith K. Effectiveness evaluation and the shoulder. In: Harryman D II, ed. The Shoulder, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1998:1313–1341.

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Instrument

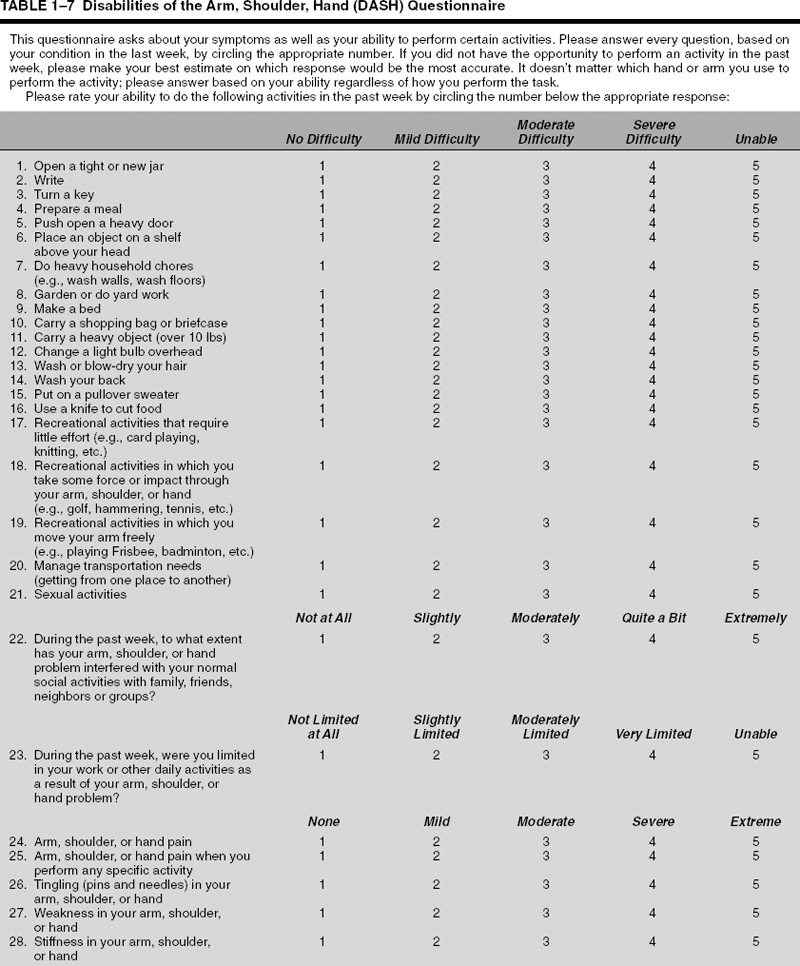

The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) Instrument began as a joint initiative of the AAOS, the Council of Musculoskeletal Specialty Societies (COMSS), and the Institute for Work and Health (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) (Table 1-7).53,54 The DASH instrument is a validated questionnaire intended to measure upper extremity symptoms and functional status during the preceding week, with a focus on physical function.54,55 The main component of the DASH instrument is the disability/symptom section, which consists of 30 questions, each with five response choices that range from “no difficulty” or “no symptom” (0 points) to “unable to perform activity” or “very severe symptom” (5 points). The scores for all items are then used to calculate a scaled disability/symptom score ranging from 0 (no disability) to 100 (severest disability) (Table 1-7). Two optional modules, each consisting of four questions, can be used to identify specific difficulties that athletes/artists or other groups of workers might experience but that may remain undetected by the disability/symptom section because these limitations may not affect their ADLs. The DASH is the upper extremity module of the MODEMS program, which was intended to establish a national database for outcomes research. The DASH is intended to be used by clinicians in daily practice. The questionnaire can be self-administered, and takes about 15 minutes to complete.

Other Outcomes Instruments

Other Outcomes Instruments

Hawkins et al56–58 has evaluated functional outcome after proximal humerus fractures by measuring the ability to perform 11 different ADLs. For each ADL, the patient assigns a value from 0 to 4 in decreasing order of difficulty: 0 indicates an inability to perform the task, whereas 4 indicates normal ability. The total score is then averaged for the 11 tasks. A good outcome is an average score of 3.5 or more; a fair outcome, 2.5 to 3.4; and a poor outcome, less than 2.5.

The Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) shoulder scoring system was designed to evaluate outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after total shoulder arthroplasty, although it has never been validated for this purpose.59 The HSS score assesses pain, function, power, and range of motion on a 100-point scale. Outcomes are stratified as follows: an excellent outcome is a score from 85 to 100 points; a good outcome, 70 to 84; a fair outcome, 50 to 69; and failure, less than 50 points.

Koval et al60 devised their own outcomes assessment to evaluate 104 patients with one-part proximal humerus fractures treated nonoperatively with a period of sling immobilization and early range of motion. Pain was graded in increasing severity on a 0 to 4 scale, with 0 indicating no pain and 4 indicating totally disabling pain. Functional ability was assessed by determining the degree of difficulty with 15 ADLs. Each task was graded on a 0 to 4 scale, with 4 indicating complete independence with the task and 0 indicating complete dependence on another individual to perform the task; the total functional score was then divided by 60 (the total possible points) to establish a percentage of function. Assessment of range of motion in forward elevation, internal rotation, and external rotation, was expressed as a percentage by comparison to the range of motion of the uninjured shoulder.

General Health Status Instruments

General Health Status Instruments

General health status instruments assess all domains of human activity, including physical, psychological, social, and role functioning. They assess the patient as a whole from the patient’s perspective. They do not refer to the specific disability or disease that is causing compromised health. The four most common general health status instruments are the Short Form-36, the Sickness Impact Profile, the Nottingham Health Profile, and the Quality of Well-Being Scale (a part of the Quality Adjusted Life Years methodology). All have been validated and are reproducible, internally consistent, and sensitive to changes in health status over time. Unfortunately, studies on outcomes of proximal humerus fractures have universally not included general health status as part of the evaluation. However, more recently, inclusion of general health status assessment has become more commonplace.

Short Form-36

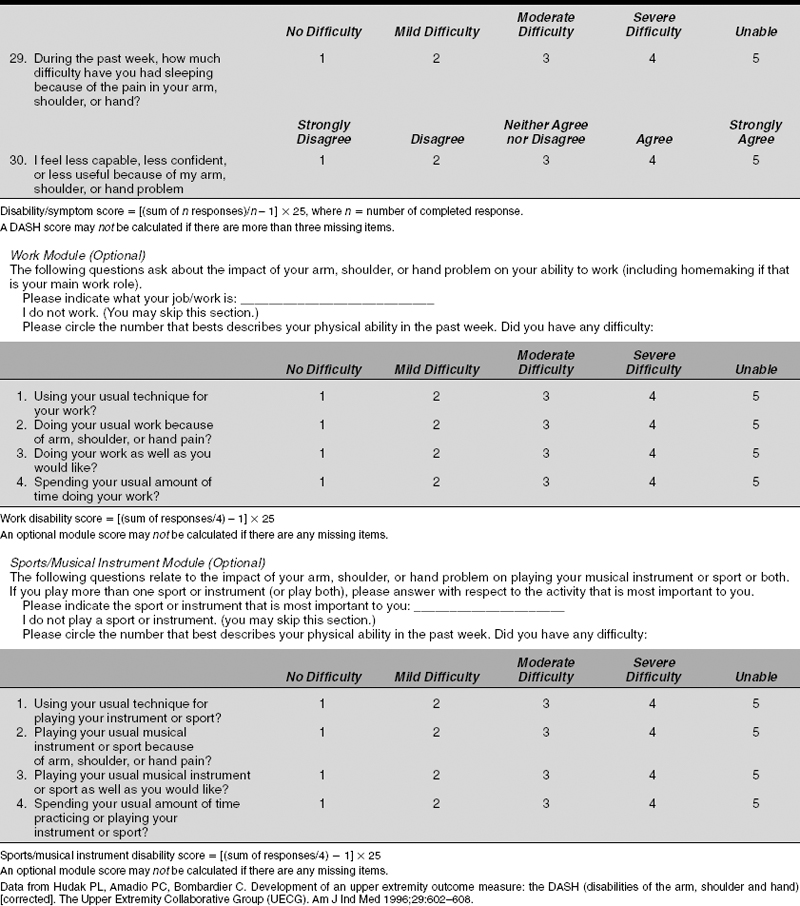

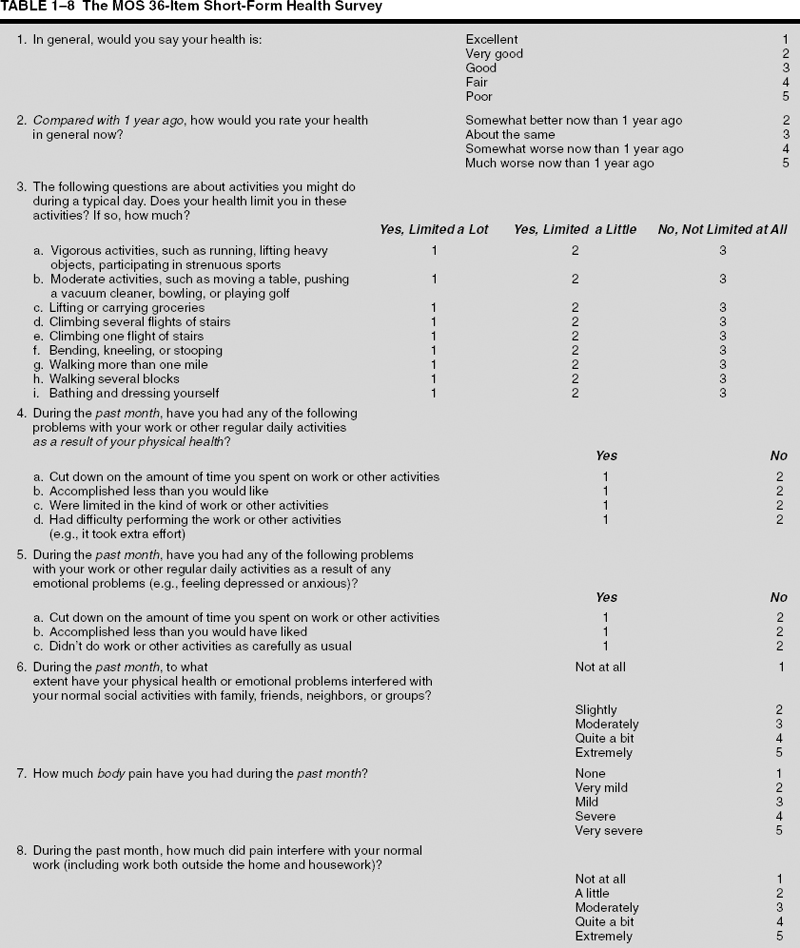

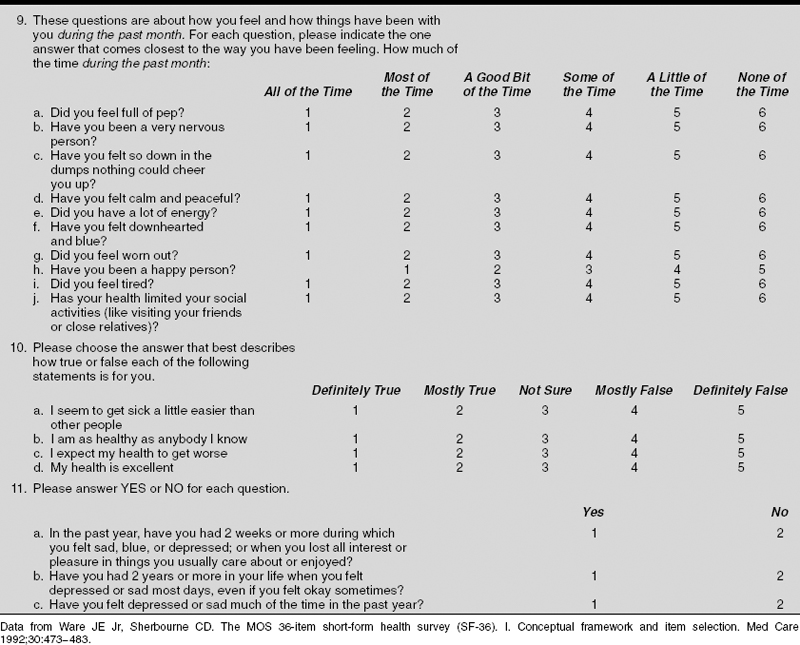

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) is the most widely used general health status instrument.61 It measures eight aspects of health: comfort or pain, energy or fatigue, physical function, physical role function, psychological role function, social role function, mental health, and general health perceptions (Table 1-8). Two summary measures can then be constructed: the physical component summary and the mental component summary. Each parameter is scored individually out of 100 points. The instrument takes about 5 to 10 minutes to complete and can be self-administered by the patient (in the office or at home), or administered by an interviewer in person or by telephone, increasing the yield of responses. Based on results from population-based control groups, the SF-36 parameters decrease with age, so results must be age-adjusted. The SF-36 has been used to study the effects of various shoulder conditions on patients’ perceptions of their general health status. Because of its wide use, the SF-36 can also be used to compare the impact of orthopaedic conditions on general health perception with the impact of other medical conditions. Gartsman et al62 demonstrated a significant decrease in general health status using the SF-36 in five common shoulder conditions (anterior instability, rotator cuff tear, adhesive capsulitis, glenohumeral degenerative joint disease, and impingement). Interestingly, the impact of these shoulder conditions on general health perception ranks in severity with that for hypertension, congestive heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, and depression. The SF-36 has also been used to assess the effects of treatments on general health status.52 Unfortunately, unless patients have used the SF 36 for unrelated medical problems, those who suffer proximal humerus fractures usually do not have the opportunity to use the SF-36 before their unexpected injury. The SF-36 does not correlate well with shoulder-specific instruments for various shoulder disorders, which confirms the need to use both shoulder-specific and general health status instruments to evaluate patients with shoulder disorders.24

Other General Health Status Instruments

Other General Health Status Instruments

The Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) is a 136-item questionnaire containing 12 domains with “yes” or “no” responses.63 The 12 domains are scored separately and combined into physical and psychological subscales. It has been used in musculoskeletal trauma.64 It is best administered by trained interviewers and takes about 25 to 35 minutes to complete. The Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) consists of a 38-item questionnaire measuring subjective general health status and a list of seven statements with “yes” or “no” responses to measure the influence of health problems on daily life.65 It has been used successfully to assess functional outcomes of limb salvage versus early amputation for complex lower extremity injuries.66 It is administered by an interviewer and takes about 10 minutes to complete. Forming the basis for the Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY) methodology, the Quality of Well-Being Scale (QWB) was developed to measure the effectiveness of treatments, which may then be used for policy analysis and resource allocation.67 Administered over 6 days, the QWB involves questions regarding physical activity, mobility, social activity, and the one problem that has bothered the patient the most on the day the questionnaire is administered. Each session of questions takes about 10 to 15 minutes to complete. Using population data multiplied by years of life expectancy and cost per intervention, the QALY or cost per year of well life expectancy is calculated. The QALY can be viewed as a quantification of the benefit of a medical treatment relative to its cost, and can be used to compare treatments with a range of financial costs for a given disease. Compared with other medical treatments, shoulder and hip arthroplasty have performed well in the analysis.45

Review of Outcomes Literature for the Treatment of Proximal Humerus Fractures

Review of Outcomes Literature for the Treatment of Proximal Humerus Fractures

The factors that affect outcome after proximal humerus fracture include the age of the patient, the type of fracture, and the type of treatment provided. The type of fracture is most commonly described using the classification described by Neer; the AO/Association for the Study of Internal Fixation (ASIF) classification is used less commonly. In the discussion that follows the outcome measure used for each study cited will be italicized. This will provide a sense of the different measures used.

Minimally Displaced (One-Part) Proximal Humerus Fractures

Approximately 85% of proximal humerus fractures are minimally displaced and are treated nonoperatively with good functional outcomes. Young and Wallace68 utilized a qualitative instrument to evaluate outcomes in patients with proximal humerus fractures. Patients who were pain free, satisfied with their shoulder function, able to place the hand above the head and behind the neck, and able to abduct above 110° were classified as having good outcomes. Patients who had the same characteristics but could only abduct to 60° were classified as having acceptable outcomes. Finally, patients with any degree of pain and dissatisfaction were classified as having poor outcomes. Ninety-seven percent of patients (33 of 34 patients) with minimally displaced fractures had good or acceptable outcomes at 6 months with nonoperative treatment and physical therapy; one patient had a poor outcome because of limited range of motion but was pain free. The authors noted that good outcomes are more likely when physical therapy is started early. Kristiansen and Christensen26 reported excellent or good outcomes in 45 of 48 patients with minimally displaced fractures at an average of 2 years using Neer’s scoring system. Using their own instrument, Koval et al60 reported excellent or good results in 80 of 104 patients at an average of 41 months. The authors suspected that the inferior outcomes in their study might have been due to the use of a more detailed assessment of functional outcome than had been used in previous investigations. Despite the lower overall scores, 90% of patients still had mild or no pain; functional recovery averaged 94%; and patients regained 88% range of motion compared with the uninjured shoulder. The percentage of good and excellent outcomes was significantly greater in patients who had started supervised physical therapy less than 14 days after the injury.

Two-Part Proximal Humerus Fractures

Using an outcomes assessment involving an 18-point scale that factors in pain, subjective opinions of the patient and physician, and range of motion, Jaberg et al69 reported 62% excellent or good results at an average of 3 years’ follow-up in a cohort of 48 patients with two-part surgical neck fractures treated with closed reduction and percutaneous pinning. The fair results were due predominantly to the patients’ subjective symptoms and decreased range of motion. Cuomo et al,70 using their own measure, evaluated pain, patient satisfaction, range of motion, and strength to assess functional outcome in 14 patients at an average of 3.3 years following two-part surgical neck fractures treated with limited ORIF using interfragmentary sutures or wire with the addition of Enders nails if comminution was present. They reported excellent or good results in 71% of patients. Using the same criteria to assess outcome in patients with two-part greater tuberosity fractures, the same authors reported excellent or good outcomes at an average of 5 years’ follow-up in a small series of 12 patients treated with ORIF with heavy, nonabsorbable suture, rotator cuff repair, and early passive motion.71 All patients had mild or no pain. Moda et al27 reported on six two-part surgical neck fractures treated with blade plates made from modified AO semitubular plates. All patients achieved excellent or satisfactory Neer scores. In a series of 97 patients at least 50 years old with displaced two-part surgical neck fractures, Court-Brown et al28 found that outcome using the Neer score was significantly correlated with age of the patient and degree of initial displacement of the fracture; poorer outcomes occurred in older patients and in those with greater initial displacement. The average Neer score at 1 year of follow-up was 78.9. It was interesting that in the subgroup of patients with at least 67% displacement/translation, there was no difference in Neer score between patients treated operatively and nonoperatively. In patients younger than 50 years, the Neer score was uniformly satisfactory to excellent.

Three-and Four-Part Proximal Humerus Fractures and Fracture-Dislocations

Most reports on treatment outcomes of three-and four-part proximal humerus fractures discuss operative results; however, Zyto72 in 1998 reported the outcomes of nonoperative treatment in 12 elderly patients with a minimum of 10 years’ follow-up. The mean Constant scores for the three-and four-part fracture groups were 59 and 47, respectively. Despite these low functional scores, all patients reported mild or no pain and all but four patients had mild or no disability. One patient developed severe osteoarthritis and two developed osteonecrosis. All patients in this small series were accepting of their shoulder condition. In a prospective, randomized trial of 40 patients comparing nonoperative treatment to tension-band wiring in three-and four-part fractures, Zyto et al23 reported comparable results in terms of pain, range of motion, power, and ADLs. Mean Constant scores were 65 for the nonoperatively treated patients and 60 for those who underwent ORIF; however, only the operative group developed complications (one case each of osteonecrosis and nonunion). Comparing nonoperative treatment, ORIF, and hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures, Zyto et al29 reported a discrepancy between Neer and Constant scores. Patients tended to score better using the Constant system compared with the Neer system. Thirty-four patients had mild or no disability according to the Constant score but only 19 had excellent or satisfactory outcomes according to the Neer score; on the other hand, 16 patients were classified as unsatisfactory or failures according to the Neer score, but only one patient had moderate to severe disability according to the Constant score. Comparing the scores with the opinions of the patients, the authors found that the Constant score more accurately assessed the subjective outcome and considered the Constant score to be more useful in elderly patients because it takes into account age and sex of the patient. In a similar study, Schai et al73 reported that functional outcome utilizing the Constant score in patients with three-part fractures was superior with operative treatment than nonoperative treatment, that four-part fracture outcomes were better following arthroplasty than nonoperative treatment or ORIF, and that three-part fracture outcomes were better than those of four-part fractures. Patients with three-part fractures treated with minimal internal fixation or ORIF had Constant scores of 83 and 91, respectively, while those with four-part fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty or ORIF had Constant scores of 74 and 52, respectively. Nonoperative treatment resulted in Constant scores of 78 for three-part fractures and 54 for four-part fractures.

Using his own outcomes instrument, Neer reported 63% excellent or satisfactory results in a cohort of 30 patients following three-part fractures treated with ORIF; this number increased to 86% when only patients treated with suture fixation of the tuberosities and cuff repair were included.31 Four-part fractures treated with ORIF uniformly failed in 13 patients, but those treated with hemiarthroplasty resulted in excellent or satisfactory outcomes in 31 of 32 patients.

Using his own outcome measure, which included pain, functional recovery with ADLs, range of motion, and strength, Stableforth21 prospectively compared the results of nonoperative treatment and hemiarthroplasty for four-part fractures. At a minimum of 18 months’ follow-up, unsatisfactory outcomes were common following nonoperative treatment due to persistent pain in nine of 16 patients, functionally inadequate range of motion in eight patients, and difficulty with ADLs in nine patients. Patients fared better after hemiarthroplasty, with 11 out of 16 patients having mild or no pain, 14 being independent with ADLs, and most regaining functional range of motion and strength. In Willem and Lim’s30 series of 10 patients with four-part fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty, at an average of 2.5 years all but one patient was pain-free but only four had excellent or satisfactory Neer scores. Poor outcomes were usually due to limited range of motion, and the authors stressed the importance of postoperative rehabilitation. Using the HSS scoring system, Moeckel et al74 reported excellent or good outcomes in 20 of 24 patients at an average of 3 years after hemiarthroplasty for three-part, four-part, and head-splitting fractures. Both age and the interval from the injury to surgery correlated inversely with outcome. Using the UCLA rating scale to evaluate two patients with three-part and 18 patients with four-part fractures treated with hemiarthroplasty, Hawkins and Switlyk57 reported excellent and good outcomes in only eight cases. Despite these low outcome scores, 18 patients had good pain relief and 16 patients were satisfied with their treatment at an average of 40 months following surgery. Poor results were documented in patients who were noncompliant with postoperative rehabilitation and had poor rotator cuff integrity and limited active range of motion.

Goldman et al75 evaluated the outcome of hemiarthroplasty in 22 patients with three-and four-part fractures using the ASES assessment instrument. Sixteen patients had slight or no pain, all patients had good to normal strength, and 20 patients had normal stability. Age over 70 years, female sex, and four-part fractures correlated with poor range of motion. Lifting, carrying a weight, and using the hand at or above shoulder level were the most common functional limitations. The authors concluded that hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures can be expected to result in pain-free shoulders, but recovery of range of motion and function were less predictable. Dimakopoulos et al32 reported similar outcomes for pain relief following hemiarthroplasty in 38 patients, but reported better range of motion and function at 1 year utilizing continuous stretching and strengthening exercises. Zyto et al76 reported disappointing Constant scores after hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures. At an average of 39 months’ follow-up, the median Constant scores were 51 and 46, respectively. Nine of the 17 patients had moderate or severe pain, and eight had moderate or severe disability. Movin et al77 reported similar disappointing results with hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty for both acute and late three-and four-part fractures in 29 patients. The mean Constant score at an average of 3 years following surgery was 38. Patients who underwent surgery within 3 weeks of injury had the same Constant score as those who were operated on later; the grouping of patients as long as 3 weeks postinjury into the acute group may have adversely affected the Constant score.

Becker et al33 looked at both the Neer and Constant scores to assess outcome at a minimum of 1 year after hemiarthroplasty for four-part fractures in 27 patients. Most deductions were due to limited range of motion; because the Constant score places considerable emphasis on range of motion, the patients had a low mean Constant score of 45. The Neer score, on the other hand, places greater emphasis on pain; because 23 of the 27 patients had mild or no pain, the mean Neer score was a relatively high 89 points. Only four patients were dissatisfied with treatment because of intermittent pain and limited range of motion, demonstrating that the overall outcome of this particular study seemed to be better represented by the Neer score than the Constant score. The authors found that a delay in surgery worsened the outcome. In their series of 39 patients at an average of 42 months following hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures, Bosch et al78 reported excellent or good results in 20%, 28%, 48%, and 72% of patients using the UCLA, Constant, HSS, and VAS scores, respectively; mean scores were 24, 54, 67, and 74, respectively. Eighty percent of patients, however, were satisfied with the outcome, and all had satisfactory pain relief. The VAS scores correlated most closely with patient satisfaction. The authors stressed that early surgery resulted in much better outcomes, especially for range of motion.

In three-part fractures and in four-part fractures that occur in young patients, reduction and fixation of the fracture is usually preferred over hemiarthroplasty. Savoie et al34 reported excellent and satisfactory Neer scores at an average of 2 years’ follow-up in all nine of their patients with three-part fractures treated with ORIF using AO/ASIF buttress plating. All patients had mild or no pain and seven returned to work. Esser79 treated three-and four-part fractures with ORIF using a modified cloverleaf plate. Twenty-four of 26 patients had good to excellent results based on evaluation with the ASES assessment. All patients were satisfied with the result and were pain free. Using the Hawkins outcomes instrument, Cornell et al58 reported good outcomes at an average of 20 months’ follow-up in 10 of 13 patients with two-and three-part fractures treated with a screw and tension band technique. All patients had mild or no pain. Using a blade plate for rigid internal fixation, Hintermann et al80 utilized their own outcomes criteria to evaluate treatment of three-and four-part fractures. Excellent outcomes involved no pain and no limitation in ADLs; good outcomes involved mild or occasional pain, and slight limitation in ADLs; fair outcomes involved moderate or frequent pain and moderate limitation in ADLs; and poor outcomes involved severe or nearly constant pain and severe limitation in ADLs. According to these criteria, 24 of 31 patients with three-part fractures and six of seven patients with four-part fractures had good or excellent outcomes at an average of 3.4 years. Despite these good results, mean Constant scores for three-and four-part fractures were only 75 and 69, respectively. Pain was usually mild, and range of motion and power were acceptable to almost all of the patients. Osteonecrosis developed in two patients. In a review of 97 patients treated with ORIF, Szyszkowitz et al35 reported 70% excellent and satisfactory Neer scores at an average of 42 months for three-part fractures, and 22% for four-part fractures. Patients treated with Kirschner wires (K-wires) or screws and cerclage wires had better outcomes than did those treated with plate fixation.

Using K-wires and tension band reinforcement, Darder et al36 had excellent and satisfactory Neer scores in 21 of 33 patients with four-part fractures at an average of 7 years’ follow-up. Despite 12 unsatisfactory outcomes based on the Neer score, all patients had good pain relief, and all except two returned to their usual daily activities and work. All cases of fracture-dislocation resulted in unsatisfactory or poor outcomes, and patients over 75 years of age obtained the worst results. Ko and Yamamoto37 reported excellent or satisfactory Neer scores at an average of 3.8 years in 14 of 16 patients treated with heavy suture or wire fixation combined with either threaded pins or external fixation for 12 three-part and 4 four-part fractures. Resch et al81 performed percutaneous reduction and screw fixation in 9 three-part and 18 four-part fractures. At an average of 2 years’ follow-up, all patients with three-part fractures had good to excellent outcomes, with an 2average Constant score of 91. Two cases of four-part fractures required revision to prostheses because of osteonecrosis and redisplacement of the fracture, respectively. In the remaining 16 cases, the outcomes were good, with an average Constant score of 87. Thirteen of the four-part fractures, however, were valgus impacted patterns, which have better prognoses. Hessmann et al38 retrospectively reviewed a cohort of 98 patients consisting of 50 two-part, 37 three-part, and 6 four-part proximal humerus fractures, and 5 three- or four-part fracture-dislocations, treated with indirect reduction and buttress plate fixation. Based on the Neer, Constant, and UCLA scores, this cohort of patients respectively had 59%, 69%, and 76% good to excellent outcomes at a minimum of 2 years. Eighty-five percent of the patients were satisfied with their result, while the remainder were unsatisfied because of either pain or loss of range of motion secondary to various complications.

Special consideration should be given to valgus impacted proximal humerus fractures because of their different prognoses, treatment, and functional outcome. In Jakob et al’s39 series of 19 patients with four-part valgus impacted fractures, 74% of patients had excellent or satisfactory Neer scores after either closed reduction or limited ORIF. Osteonecrosis occurred in 26% of the cases and accounted for all of the poor outcomes. Union occurred in all patients. In a later review of 125 patients with AO B1.1 valgus impacted fractures treated nonoperatively with 2 weeks of immobilization, Court-Brown et al40 reported 81% excellent or satisfactory Neer scores at an average follow-up of 1 year. The average Neer score for B1.1 valgus impacted fractures that were minimally displaced was 90.3, whereas average Neer scores for those associated with displacement of the greater tuberosity, surgical neck, or both, were 88.4, 84.3, and 81.3, respectively, suggesting worse functional outcome with more severe fractures. The authors recommended nonoperative treatment for all valgus impacted fractures. They did not report the incidence of osteonecrosis.

Summary of Outcomes Instruments in Proximal Humerus Fractures

Summary of Outcomes Instruments in Proximal Humerus Fractures

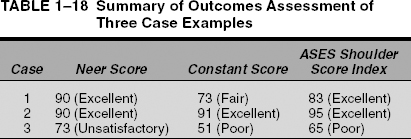

As is evident from this literature review, currently utilized outcome scores contain shortcomings that may misrepresent patient perceptions of treatment outcomes. In Zyto’s72 1998 study on outcomes of nonoperative treatment in three-and four-part fractures, despite having low mean Constant scores of 59 and 47, respectively, all patients had mild or no pain, eight of 12 patients had mild or no disability, and all patients were accepting of their disability. Based on pain relief and ability to carry out ADLs, Hintermann et al80 reported good or excellent subjective outcomes in 24 of 31 patients treated with ORIF for three-part and six of seven patients with four-part fractures, despite low mean Constant scores of 75 and 69, respectively. Although Hawkins and Switlyk57 reported excellent and good UCLA scores in only eight of 20 patients treated with hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures, 18 out of the 20 patients had good pain relief and 16 patients were still satisfied with their treatment. In Darder et al’s36 study of tension-band wiring of four-part fractures, 12 patients had unsatisfactory Neer scores, yet all 33 patients in the study had good pain relief and all except two returned to usual daily activities and work. Patients may lack full range of motion and strength—objective measures that are often weighed heavily in outcomes instruments—yet remain satisfied with a pain-free shoulder and restoration of a functional range of motion. These examples demonstrate how currently utilized outcomes scores do not always correlate with patient perceptions of treatment outcomes.

Disparity exists among the various outcomes instruments because each one emphasizes different aspects of the evaluation; for example, one instrument may emphasize pain; another, range of motion; still another, functional capacity with ADLs. This disparity is particularly evident in studies that report multiple scoring systems. In Zyto et al’s29 comparison of nonoperative treatment, ORIF, and hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures, patients tended to score better using the Constant system compared with the Neer system. Thirty-four patients had mild or no disability according to the Constant score, but only 19 had excellent or satisfactory outcomes according to the Neer score. Furthermore, 16 patients were categorized as unsatisfactory or failures by the Neer system, but only one patient had moderate to severe disability according to the Constant system. Moreover, the authors found that the Constant score more closely reflected the subjective outcomes of the patients and concluded that the Constant score was more useful in elderly patients. In contrast to these results, Becker et al33 found that the Neer score better represented the overall patient satisfaction than the Constant score in their study of hemiarthroplasty for four-part fractures. Although 23 of 27 patients had good pain relief, many had restricted range of motion, accounting for most of the deductions. Because the Constant score places considerable emphasis on range of motion, patients had a low mean Constant score of 45. On the other hand, because the Neer score places greater emphasis on pain, the Neer score was a relatively high 89 points. This result supports the premise that patients are frequently satisfied by good pain relief and restoration of at least a functional range of motion, despite having mild limitations in overall range of motion or strength. Using the Neer score to assess outcome following indirect reduction and internal fixation for two-, three-, and four-part fractures and fracture-dislocations, Hessmann38 et al reported good to excellent results in only 59% of patients; when assessed with the Constant and UCLA scores, the percentage of good to excellent outcomes rose to 69% and 76%, respectively. Even greater disparities among outcome scores were found by Bosch et al78 in their reporting of outcomes following hemiarthroplasty for three-and four-part fractures. Utilization of the Constant and UCLA scores resulted in good to excellent outcomes in only 28% and 20% of patients. When assessed with the HSS and VAS scores, the percentage of excellent or good outcomes rose to 48% and 72%, respectively. The disparity in outcomes of the four instruments reinforces the point that emphasis is placed on different aspects of the shoulder evaluation in each of the four instruments. These inherent differences in the various outcome measures contribute to their limited ability to make comparisons between studies and derive definitive conclusions regarding treatments.

Case Reports

Case Reports

Case 1

The patient is a 74-year-old right-hand dominant woman who complains of right shoulder pain after slipping in her bathroom and falling onto an outstretched right hand. On physical examination the patient was found to have moderate swelling and ecchymosis about her right shoulder. Palpation revealed tenderness around her proximal humerus. Range of motion was limited in all directions due to pain. Manipulation revealed slight crepitus of the shoulder. Neurologic examination revealed intact sensation in the axillary, radial, median, and ulnar nerve distributions. Motor examination demonstrated firing of the lateral deltoid. Radiographs demonstrated a surgical neck fracture of the right proximal humerus with 10° of varus angulation and 4 mm of medial translation. The patient was treated initially in a shoulder sling. At 12 days following the injury, the patient was started on a regimen of supervised physical therapy consisting of active range of motion exercises for the elbow, wrist, and hand, in combination with assisted passive range of motion exercises for the injured shoulder. The patient attended physical therapy sessions twice each week and performed the exercises three times daily at home. At 5 weeks following the injury there was clinical and radiographic evidence of fracture union and the sling was discontinued. Active shoulder range of motion exercises and isometric deltoid and rotator cuff strengthening exercises were then begun. At 9 weeks following the injury, after achievement of good active shoulder motion, isotonic deltoid and rotator cuff strengthening exercises were initiated, followed by a more vigorous stretching program at 12 weeks.

Supervised physical therapy was continued for the next 2 months, and the patient was encouraged to continue with her exercises at home after this time. At 3 years following her injury, the patient was pain free and had no symptoms of instability; however, she continued to be unable to sleep on the affected shoulder. She had mild difficulty with reaching high on a shelf, clasping/unclasping her bra, combing her hair, and throwing a ball overhead. Examination of active and passive range of motion revealed forward elevation to 130°, external rotation at the side to 40°, and internal rotation to T12. Strength in all shoulder motions was 5/5, and she was able to hold a 10-pound weight with her affected shoulder in 90° of abduction. Radiographs demonstrated slight residual angulation but full union. Tables 1-9, 1-10, and 1-11 illustrate the patient’s Neer, Constant, and ASES scores. With the Neer score weighing heavily pain and function, the patient scored an excellent outcome (90 points). In contrast, with its emphasis on the objective measures of range of motion and strength, her Constant score (73 points) reflected fair outcome. The shoulder score index of the ASES score weighs only the subjective measures of pain and function, and the patient scored a good outcome (83 points). Overall, the patient was satisfied with her treatment.

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pain | None | 35/35 |

| Function | ||

| Strength | Good | 8/10 |

| Reaching | ||

| Top of head | 1/2 | |

| Mouth | 2/2 | |

| Belt buckle | 2/2 | |

| Opposite axilla | 2/2 | |

| Brassiere hook | 1/2 | |

| Stability | ||

| Lifting, throwing, | 10/10 | |

| pounding, pushing, | ||

| hold overhead | ||

| Range of motion | ||

| Flexion | 130° | 4/6 |

| Extension | 30° | 2/3 |

| Abduction | 140° | 4/6 |

| (coronal plane) | ||

| External rotation | 40° | 5/5 |

| Internal rotation | T12 | 4/5 |

| Radiograph | Union, no malunion | 10/10 |

| Overall score | Excellent | 90/100 |

| Patient satisfaction | Yes | |

| with outcome: |

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pain | None | 15/15 |

| ADL | ||

| Activity | ||

| Work | Mild limitation | 3/4 |

| Recreation/sport | Mild limitation | 3/4 |

| Sleep | Unaffected | 0/2 |

| Positioning: | ||

| behind head | 8/10 | |

| Range of motion | ||

| Forward elevation | 130° | 8/10 |

| Lateral elevation | 140° | 8/10 |

| External rotation: hand behind head with elbow held back | 8/10 | |

| Internal rotation | T12 | 8/10 |

| Power | 10 pounds | 10/25 |

| Overall score | Fair | 73/100 |

Case 2

The patient is a 58-year-old right-hand-dominant man who complains of right shoulder pain after falling off his bicycle during an amateur race. On physical exam, considerable swelling and ecchymosis was noted about his right shoulder and point tenderness over the proximal aspect of his right arm. There was crepitus on attempted range of motion, which was limited by pain and guarding. The patient had no neurologic deficits, and active firing of the deltoids could be elicited. Radiographs demonstrated a surgical neck fracture of the right proximal humerus with 50° of varus angulation and 2 cm of medial displacement, along with a greater tuberosity fracture with 1 cm of displacement. Closed reduction was attempted under conscious sedation in the emergency room, but residual angulation and displacement was noted on postreduction radiographs. At this point, the patient was taken to the operating room and open reduction with tension-band wiring was performed under general anesthesia. Intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging demonstrated anatomic reduction. Postoperatively, the patient was discharged with sling immobilization until the following day, when supervised active range of motion of the elbow, wrist, and hand and passive range of motion of the affected shoulder were started with a supervised physical therapy program. At 6 postoperative weeks, radiographs demonstrated fracture union and the sling was discontinued. Isometric deltoid and rotator cuff strengthening was then begun, along with active shoulder range of motion exercises. Good active shoulder motion was achieved at 9 weeks, at which time resistive strengthening exercises were initiated and stretching was progressed. After the completion of supervised physical therapy sessions, the patient continued to perform his exercises at a gym near his home.

| Points | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain: | None | VAS score: 0/10 | |

| Pain score: 0/10 | |||

| Subjective instability | Very stable | VAS score: 0/10 | |

| ADL | |||

| Put on a coat | Not difficult | 3/3 | |

| Sleep on affected side | Unable | 0/3 | |

| Wash back/do up bra | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Toileting | Not difficult | 3/3 | |

| Comb hair | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Reach high shelf | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Lift 10 lbs above shoulder | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Throw ball overhand | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Work | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Sports | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Cumulative ADL score: 20/30 | |||

| Active range of motion | |||

| Forward elevation | 130° | ||

| External rotation (arm at side) | 40° | ||

| External rotation (arm at 90° abduction) | 40° | ||

| Internal rotation | T12 | ||

| Cross-body | Opposite shoulder adduction | ||

| Passive range of motion | |||

| Forward elevation | 130° | ||

| External rotation (arm at side) | 40° | ||

| External rotation (arm at 90° abduction), head | 40° with elbow held back | ||

| Internal rotation | T12 | ||

| Cross-body adduction | Opposite shoulder | ||

| Physical findings/signs | Mild crepitus | ||

| Strength | |||

| Forward elevation | 5/5 | ||

| Abduction | 5/5 | ||

| External rotation (arm at side) | 5/5 | ||

| Internal rotation (arm at side) | 5/5 | ||

| Objective instability | None | ||

Shoulder Score Index = [(10 – Pain VAS) × 5] + [(5/3) × cumulative ADL score] = 50 + 33 = 83

At the 3-year follow-up visit the patient was pain free and had no instability symptoms. With the exception of mild difficulty with such overhead sports as throwing, the patient had no difficulties with ADL, work, or other recreational activities. Examination of active and passive range of motion revealed forward elevation to 150°, external rotation at the side to 50°, and internal rotation to T10. The patient was able to lift the full 25-pound weight with the affected arm abducted to 90° during strength testing for the Constant score, although strength was slightly less compared with the unaffected shoulder. X-rays demonstrated no malunion or osteonecrosis. Tables 1-12, 1-13, and 1-14 show the Neer, Constant, and ASES scores for this patient at the most recent follow-up. In contrast to the patient in Case 1, who had an excellent Neer score but only a good Constant score and shoulder score index, the patient in Case 2 was rated an excellent result on all three scoring systems: Neer score 90 points, Constant score 91 points, and ASES shoulder score index 95 points. The higher Constant score compared with Case 1 can be attributed to the emphasis of the objective measure of strength, which was full for this patient. The additional 10 points elevated this patient’s Constant score to excellent. The ability to perform ADLs explains the excellent ASES shoulder score index. Overall, he was quite satisfied with his outcome.

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pain | None | 35/35 |

| Function | ||

| Strength | Good | 8/10 |

| Reaching | ||

| Top of head | 2/2 | |

| Mouth | 2/2 | |

| Belt buckle | 2/2 | |

| Opposite axilla | 2/2 | |

| Brassiere hook | 2/2 | |

| Stability | ||

| Lifting, throwing, pounding, | 10/10 | |

| pushing, hold overhead | ||

| Range of motion: | ||

| Flexion | 150° | 4/6 |

| Extension | 35° | 2/3 |

| Abduction (coronal plane) | 160° | 4/6 |

| External rotation | 50° | 3/5 |

| Internal rotation | T10 | 4/5 |

| Radiograph | Union, no malunion | 10/10 |

| Overall score | Excellent | 90/100 |

| Patient satisfaction with outcome | Yes |

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pain | None | 15/15 |

| ADL | ||

| Activity: | ||

| Work | Unaffected | 4/4 |

| Recreation/sport | Mild limitation | 3/4 |

| Sleep | Unaffected | 2/2 |

| Positioning | Above head | 10/10 |

| Range of motion: | ||

| Forward elevation | 150° | 8/10 |

| Lateral elevation | 150° | 8/10 |

| External rotation: Hand behind head with elbow held back | 8/10 | |

| Internal rotation | T10 | 8/10 |

| Power: | 25 pounds | 25/25 |

| Overall score | Excellent | 91/100 |

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pain | None | VAS score: 0/10 |

| Pain score: 0/10 | ||

| Subjective instability | Very stable | VAS score: 0/10 |

| ADL: | ||

| Put on a coat | Not difficult | 3/3 |

| Sleep on affected side | Not difficult | 3/3 |

| Wash back/do up bra | Not difficult | 3/3 |

| Toileting | Not difficult | 3/3 |

| Comb hair | Not difficult | 3/3 |

| Reach high shelf | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 |

| Lift 10 lbs above | Not difficult | 3/3 |

| shoulder | ||

| Throw ball overhand | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 |

| Work | Not difficult | 3/3 |

| Sports | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 |

| Cumulative ADL score: 27/30 | ||

| Active range of motion | ||

| Forward elevation | 150° | |

| External rotation | 50° | |

| (arm at side) | ||

| External rotation | 50° | |

| (arm at 90° abduction) | ||

| Internal rotation | T10 | |

| Cross-body | Opposite shoulder | |

| adduction | ||

| Passive range of | ||

| motion: | ||

| Forward elevation | 150° | |

| External rotation (arm at side) | 50° | |

| External rotation (arm at 90° | 50° | |

| abduction), head with elbow | ||

| held back | ||

| Internal rotation | T10 | |

| Cross-body adduction | Opposite shoulder | |

| Physical findings/signs | Scar | |

| Strength | ||

| Forward elevation | 5/5 | |

| Abduction | 5/5 | |

| External rotation | 5/5 | |

| (arm at side) | ||

| Internal rotation (arm at side) | 5/5 | |

| Objective instability | None | |

Shoulder Score Index = [(10 – Pain VAS) × 5] + [(5/3) × cumulative ADL score] = 50 + 45 = 95

Case 3

A 69-year-old left-hand dominant woman presents with left shoulder pain and an inability to move her left shoulder after slipping and falling on her kitchen floor. Physical exam revealed an anterior prominence and squaring-off of the posterolateral acromion. There was tenderness to palpation in the left proximal humerus and pain with attempted motion. Neurologic examination revealed decreased sensation in the lateral aspect of the shoulder. Radiographs demonstrated a four-part anterior fracture-dislocation of the proximal humerus. Under conscious sedation, an attempt at closed reduction was made in the emergency room but was unsuccessful. The decision was made to take the patient to the operating room, where she underwent hemiarthroplasty of the injured shoulder 36 hours after her initial injury. At the time of surgery, the long head of the biceps was found to be interposed between the fracture fragments. The patient wore a shoulder sling and on postoperative day 1 was started on a supervised physical therapy regimen involving active range of motion of the elbow, wrist, and hand, along with pendulum exercises for the affected shoulder. Passive assisted range of motion exercises were continued until union of the tuberosities was evident 6 weeks after the procedure. At this point, the sling was discontinued, active assisted range of motion exercises and isometric deltoid and rotator cuff exercises were initiated. Isotonic deltoid and rotator cuff strengthening was begun at 10 weeks postoperative, in combination with a more aggressive stretching program. Supervised physical therapy continued for the next 4 months, after which time the patient continued her exercises unsupervised at home.

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Slight | 30/35 |

| Function | ||

| Strength | Fair | 6/10 |

| Reaching | ||

| Top of head | 1/2 | |

| Mouth | 2/2 | |

| Belt buckle | 2/2 | |

| Opposite axilla | 1/2 | |

| Brassiere hook | 0/2 | |

| Stability | ||

| Lifting, throwing, pounding, | 10/10 | |

| pushing, hold overhead | ||

| Range of motion | ||

| Flexion | 100° | 2/6 |

| Extension | 20° | 1/3 |

| Abduction (coronal plane) | 100° | 2/6 |

| External rotation | 30° | 3/5 |

| Internal rotation | L2 | 3/5 |

| Radiograph | Prosthesis well aligned, no radiolucencies | 10/10 |

| Overall score | Unsatisfactory | 73/100 |

| Patient satisfaction | Yes | |

| with outcome |

At the 3-year follow-up visit, the patient reported only intermittent pain with heavy lifting or strenuous activity. She had difficulty with ADLs, particularly involving overhead activity and lifting, but was able to remain independent in most activities. She had no subjective complaints of instability. Examination of active and passive range of motion revealed forward elevation to 100°, external rotation at the side to 30°, and internal rotation to L2. She had supraspinatus tenderness and a positive impingement sign. Strength testing demonstrated that she could hold a 5-pound weight while holding her shoulder in 90° of abduction. Radiographs demonstrated good alignment of the prosthesis and no evidence of loosening. Tables 1-15, 1-16, and 1-17 show that the patient scored an unsatisfactory Neer score (73 points), a poor Constant score (51 points), and poor ASES shoulder score index (65 points). Despite these low functional scores, the patient accepted her mild degree of pain and, overall, was satisfied with her outcome. The scores of these three case examples are summarized in Table 1-18.

| Points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Mild | 10/15 |

| ADL | ||

| Activity | ||

| Work | Mild limitation | 2/4 |

| Recreation/sport | Mild limitation | 2/4 |

| Sleep | Unaffected | 8/2 |

| Positioning: top of head | 6/10 | |

| Range of motion: | ||

| Forward elevation | 100° | 6/10 |

| Lateral elevation | 100° | 6/10 |

| External rotation: hand on top of head with elbow held forward | 6/10 | |

| Internal rotation | L2 | 6/10 |

| Power | 5 pounds | 5/25 |

| Overall score | Poor | 51/100 |

Conclusion

Conclusion

Clinical assessment using objective measures, such as range of motion, strength, and radiographic union alone, often does not accurately reflect treatment outcome. Subjective, patient-oriented assessments must be added to the evaluation to obtain a full impression of the outcome. Outcomes research involves many methodologies to determine the effectiveness of treatments, but it relies most heavily on clinical research studies with clearly defined patient-oriented outcome measures. The ideal research tool is the prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial with clearly defined end points for measurement and comparison. Unfortunately, few orthopaedic studies have adhered to this study design. This is particularly true in the area of proximal humerus fractures.

| Points | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | None | VAS score: 2/10 | |

| Pain score: 2/10 | |||

| Subjective instability | Very stable | VAS score: 0/10 | |

| ADL | |||

| Put on a coat | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Sleep on affected side | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Wash back/do up bra | Very difficult | 1/3 | |

| Toileting | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Comb hair | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Reach high shelf | Very difficult | 1/3 | |

| Lift 10 lbs above | Very difficult | 1/3 | |

| shoulder | |||

| Throw ball overhand | Unable | 0/3 | |

| Work | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Sports | Somewhat difficult | 2/3 | |

| Cumulative ADL score: 15/30 | |||

| Active range of motion | |||

| Forward elevation | 100° | ||

| External rotation | 30° (arm at side) | ||

| External rotation (arm at 90° abduction) | 30° | ||

| Internal rotation | L2 | ||

| Cross-body adduction | Mid-chest | ||

| Passive range of motion: | |||

| Forward elevation | 100° | ||

| External rotation | 30° (arm at side) | ||

| External rotation (arm at 90° abduction), head with elbow held back | 30° | ||

| Internal rotation | L2 | ||

| Cross-body adduction | Mid-chest | ||

| Physical findings/signs | Supraspinatus tenderness, impingement, mild crepitus, scar | ||

| Strength | |||

| Forward elevation | 4+/5 | ||

| Abduction | 4+/5 | ||

| External rotation (arm at side) | 4+/5 | ||

| Internal rotation (arm at side) | 5/5 | ||

| Objective instability | None | ||

Shoulder Score Index = [(10 – Pain VAS) × 5] + [(5/3) × cumulative ADL score] = 40 + 25 = 65

Based on the literature, the treatment of minimally displaced proximal humerus fractures is clear: non-operative treatment involving brief immobilization and early range of motion; however, the treatment of displaced, unstable proximal humerus fractures is not as clearly defined. One method of outcomes research, meta-analysis, utilizes a comprehensive literature review to pool data from multiple studies to gain stronger statistical power for analysis. Because of the lack of well-designed, prospective randomized studies, however, attempts at meta-analysis to determine the most effective treatments for unstable proximal humerus fractures have failed to determine definitive treatment recommendations. To eliminate bias and produce the most valid results, future orthopaedic research should strive to adhere to the prospective, randomized, controlled design.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree