Chapter 47 Principles of Therapy, Local Measures, and Nonsteroidal Medications

Formulation Overview

1. Does the patient meet the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE?

2. If the patient has SLE, is it organ threatening and therefore could potentially shorten lifespan (e.g., cardiopulmonary involvement, renal disease, hepatic involvement, central nervous system vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, or autoimmune hemolytic anemia)? If not, does the patient have non–organ-threatening SLE (e.g., cutaneous, musculoskeletal, serositis, constitutional)?

3. Which subset best describes the disease? Does a particular aspect of the patient’s disease require specific considerations, interventions, or counseling (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome, Sjögren syndrome antigen A [SSA/Ro] positivity, seizures, concurrent fibromyalgia)?

Educational Session

All patients who are newly diagnosed, as well as those who are new to the treating physician, deserve an educational session that includes concerned family members, friends, and significant others. The session should be supervised by the physician and may involve other health professionals or use audiovisual aids. Several studies have demonstrated that socioeconomic differences account for the widely divergent outcomes in those with SLE (see Chapter 55). It is critical that the patient establish a relationship and rapport with the treating facility or physician, speak a common language, keep appointments, take medication as prescribed, have transportation to the medical office, and have access to medical assistance or advice 24 hours a day. Educational aids, online assistance, and informational literature relating to the various aspects of the disease, including therapy, are available from lupus support organizations such as those listed in the Appendix.

The treatment of SLE includes physical and psychological measures, surgery, and medications. Box 47-1 summarizes the issues that should be discussed with the patient and family during the educational session. (Topics listed in Box 47-1 not covered elsewhere in this textbook are reviewed in the following text, and the reader is also referred to the index.)

Box 47-1

Curriculum for the Educational Session with a Patient Who Is Newly Diagnosed with Lupus or Is New to the Practice Setting

1. What is lupus? What are its causes?

2. Many types of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) exist: cutaneous, mild, drug-induced, and organ-threatening, all of which have a (fair, good, excellent) prognosis with treatment.

3. Physical and lifestyle measures to be reviewed:

5. Being current with adjunctive measures:

General Therapeutic Considerations

Rest, Sleep, and the Treatment of Fatigue

Fatigue is present in 50% to 90% of patients with SLE and can be its most disabling symptom.1 Potentially reversible causes of fatigue should first be ruled out. These include active inflammation, complications from medication, and co-morbid states such as psychosocial stressors. Occasionally, patients with normal examinations, an absence of acute-phase reactants, and normal chemistry panels (other than a positive ANA test) complain of profound fatigue. The administration of certain cytokines is known to induce fatigue.2 Reduced muscle aerobic capacity may also play a role.3 Sleep quality in patients with SLE is impaired.4 One survey showed that 80% of 172 patients with SLE have disordered sleep, compared with 28% of healthy patients in the control group. Disordered sleep is most likely due to depressed mood, fibromyalgia, steroid therapy, and a lack of exercise.4,5 Fatigue surveys have statistically associated it with aerobic insufficiency, pain, depression, disordered sleep, altered perceived social support, and a higher Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC)/ACR Damage Index (SDI).6 Fifteen instruments have been evaluated in fatigue-associated SLE in 34 studies, and the fatigue severity scale is regarded as having the best overall results with regard to showing a minimally clinically important difference.7

Treatment of fatigue requires consideration of the source and contributory factors. Iron deficiency anemia is common because of dietary deficiency, heavy menstrual periods, and/or blood loss resulting from the use of salicylates and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). If the fatigue is caused by parenchymal pulmonary disease, then oxygen may be helpful; if it is secondary to inflammation, then antiinflammatory drugs are used. In addition to corticosteroid medications, quinacrine and hydroxychloroquine are cortical stimulants and may decrease fatigue in patients without organ-threatening involvement.8 Dehydroepiandrosterone (5-DHEA), modafinil (Provigil), armodafinil (Nuvigil), bupropion, and selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors can be useful. Depression, fibromyalgia, and emotional stress must be excluded as causes. Several surveys have suggested that fibromyalgia and depression are the most common causes of fatigue in patients with SLE.9 Secondary fibromyalgia with a concomitant sleep disorder is not uncommon. Some physicians empirically prescribe low doses of thyroid, vitamin B12 injections, or amphetamines for nonspecific fatigue of SLE; however, the routine use of these agents should be discouraged. In contrast, the use of anxiolytic agents, especially those that promote restorative sleep, should be considered (Box 47-2).

Box 47-2

Fatigue in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

1. Present in 50% to 90% of patients according to multiple surveys

Exercise, Physical Therapy, and Rehabilitation

Six well-designed studies have evaluated aerobic conditioning in patients with SLE. They concluded that aerobic capacity is decreased by 30% to 40% but does not necessarily correlate with disease activity or damage. However, SLE is associated with fatigue, cardiovascular functioning, obesity, bone mineralization, sleep, and quality of life.10,11 Exercise regimens improve physical functioning and fatigue.12–14 The patient with SLE should remain physically active and avoid excessive bed rest. Exercises that strengthen muscles and improve endurance while avoiding undue stress to inflamed joints are desirable. Activities such as swimming, walking, low-impact aerobics, and bicycling should be encouraged. Recreational activities involving fine-motor movements and placing stress on certain ligamentous and other supporting structures (e.g., bowling, rowing, weight lifting, golf, tennis, jogging) should be considered on an individual basis. Exercises involving sustained isometric contractions increase muscle strength more than isotonic exercises (e.g., stretching, Pilates). Physical measures, such as the use of local moist heat or cold, decrease joint pain and inflammation. Many patients benefit from a whirlpool bath (Jacuzzi), hot tub, or therapy pool or from merely soaking in a tub of hot water.

Tobacco Smoke and Alcohol

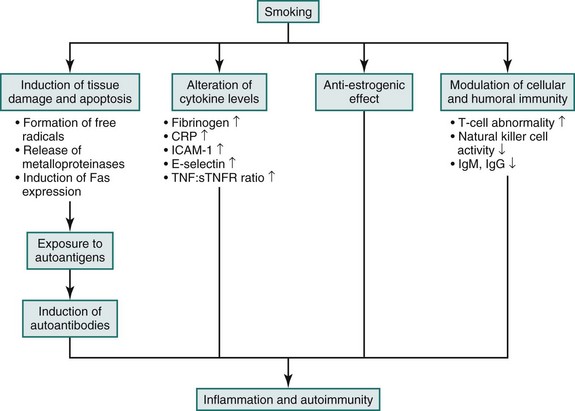

Tobacco use can cause tissue damage by inducing apoptosis, altering cytokine and hormone balances, influencing immunogenesis of self-antigens and lymphocyte function that can, in turn, promote autoimmunity.15 Clinically, smoking impairs oxygenation, raises blood pressure, promotes the formation of autoantibodies, and worsens Raynaud phenomenon, among other adverse actions (Figure 47-1). Numerous reports correlate tobacco use with worse cutaneous lupus or disease activity than among nonsmokers.16–18 Additional comparisons have confirmed that chronic cutaneous lupus is more common in smokers than in nonsmokers, as is SLE.19 Two epidemiologic surveys19,20 associate smoking with 2.3 and 6.69 odds ratios for developing SLE. Because tobacco smoke contains potentially lupogenic hydrazines, abstinence and avoiding second-hand smoke are both important. The efficacy of antimalarial medications may be decreased in smokers, perhaps as a result of the effect of tobacco on the cytochrome P450 enzyme system that metabolizes chloroquines.21,22

Although alcohol can worsen reflux esophagitis, which is common in patients with SLE, and is not advised in patients taking methotrexate, approximately 10 studies have addressed the issue with conflicting results. Moderate drinking might be protective for patients with SLE, but a metaanalysis of 7 case-controlled studies and 2 cohort studies found an overall 1.5 odds ratio for developing SLE among those who drink alcohol.16,17,20,23,24

Weather and Seasons

Changes in barometric pressure can aggravate stiffness and aching in patients with inflammatory arthritis.25 In other words, whether the climate is hot or cold or wet or dry, it does not influence joint symptoms; however, changes in the weather do aggravate joint symptoms (e.g., hot to cold or wet to dry). Patients with lupus are counseled to expect some increased stiffness and aching in these circumstances and not to assume that they have done anything wrong. Several surveys of seasonality and weather in patients with SLE have been conducted, but no conclusions have been independently confirmed other than to suggest that more flares and phototoxicity happen in the summer months and weakness, fatigue, and Raynaud phenomenon more often occur in the winter months.26–28

Pain Management

Patients with lupus have increased prevalence of problems with pain management.29,30 Individuals with inflammatory arthritis respond poorly to analgesic medications that have no antiinflammatory effects. The use of morphine and codeine derivatives in patients with SLE should be limited to postoperative management and functionally limiting fixed mechanical deformities. These agents can induce dependence, have short-lived effects, and do not address SLE-related inflammation. Antiinflammatory drugs (e.g., salicylates, NSAIDs, corticosteroids) can be effective in treating pain symptoms in patients with SLE. Some patients with chronic pain that is unresponsive to simple measures should be referred to pain-management centers, which use measures such as acupuncture, electrical stimulation, biofeedback, psychological counseling, and physical therapy to alleviate pain and eliminate narcotic dependence. Anxiolytic measures that work with the mind-body connection are useful as well. Other causes of pain in patients with SLE include avascular necrosis, headache, steroid-induced hyperesthesia, and fibromyalgia.

Role of Stress and Trauma

In a general sense, certain forms of emotional stress, including depression and bereavement, as well as physical trauma can affect the immune system by being associated with decreased lymphocyte mitogenic responsiveness, lymphocyte cytotoxicity, increased natural killer (NK)–cell activity, skin homograft rejection, graft-versus-host response, and delayed hypersensitivity.31,32 The clinical sequelae of stress are difficult to characterize and quantitate. Could the impairment in T-cell immune functions be responsible for a clinical flare of lupus that is mediated by B-cell hyperreactivity? Acute stress in patients with SLE may correlate with increased urine neopterin levels, interleukin (IL) 4 levels, decreased NK-cell response, and increased numbers of beta-2 adrenergic receptors on mononuclear cells with or without a clinical disease flare.33,34 However, evidence-based validation of this in a rigorous, reproducible clinical setting is lacking.

Can Stress Induce Lupus?

In 1955, McClary and colleagues35 first related the onset of disease to significant crises in interpersonal relationships in 13 of 14 patients with SLE. Subsequent reports have reinforced patient perceptions that stress caused their SLE, but the hypothesis remains unproven.

Can Stress Exacerbate Preexisting Systemic Lupus Erythematosus?

Ropes36 first addressed this question over 50 years ago and observed 45 serious disease flares in her 160-patient cohort study over a 40-year period. Of the 45 patients with serious disease flares, 41 believed that emotional stress precipitated their flare. The development and validation of quality-of-life inventories, fatigue questionnaires, and function scores have correlated disease activity with psychosocial stressors in a general way, but the mechanism by which this correlation may occur has not been elucidated.37–39 A devastating earthquake was associated with disease improvement in one study, and no change in another.40,41

Can Physical Trauma Cause or Exacerbate Systemic Lupus Erythematosus?

No evidence has shown that physical trauma is related to the causation or exacerbation of SLE. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus can develop as a result of physical trauma; King-Smith42 first observed this response to physical trauma in 1926. Approximately 2% of all chronic cutaneous lesions occur in areas of physical trauma.43

How Important ARE Patient Compliance and Treatment Adherence?

Dr. C. Everett Koop, the former Surgeon General of the United States, is reported to have said, “Drugs don’t work in patients who don’t take them.”44

Part of the patient educational session with a new patient with lupus must be a discussion relating to compliance. In the LUMINA Texas and Alabama–based cohort study, nearly one half of the patients were noncompliant. They tended to be young, unmarried, African American, and ill.45 Adherence to treatment regimens tends to be problematic. One third of 195 patients of Canadian descent with lupus did not participate in mandated annual eye examinations to monitor antimalarial therapies.46 Compliance problems among 112 patients with lupus in Detroit were related to depression, medication concerns, physical symptoms, short-term memory problems, and the need for child or elder care.47 Other important factors include previous medication experiences, strong beliefs in alternative methods, communication issues, low educational levels, cultural concerns, very high rates of noncompliance in adolescents, and cost. The failure to comply with physician recommendations was shown to be the cause of renal failure in 5 of the 17 patients in a study conducted at the University of Toronto.48 In Great Britain, the rate of compliance was treatment specific among 50 women with SLE, ranging from 41% for the use of sun protection to 83% for the use of hydroxychloroquine, 94% for the use of steroids, and 100% for the use of azathioprine therapy.49 Ninety-five patients at the University of Cincinnati had a similar outcome when pharmacy refill records were examined using a statistically validated compliance metric.50 Adherence to treatment plans is a critical component in managing SLE, and strategies to address this issue need to be more fully developed and implemented.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree