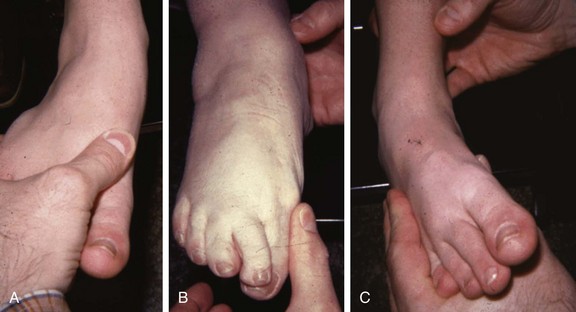

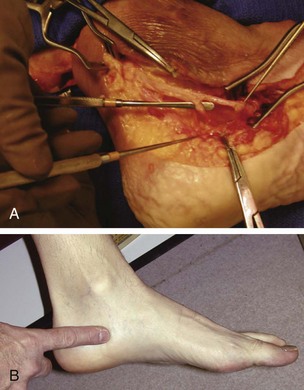

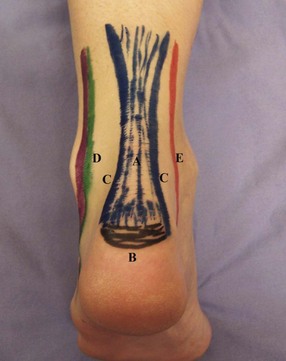

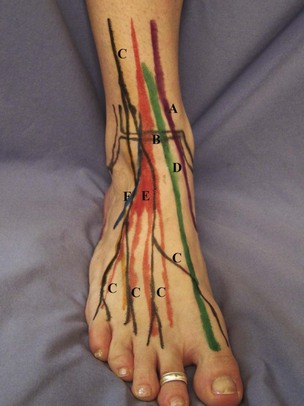

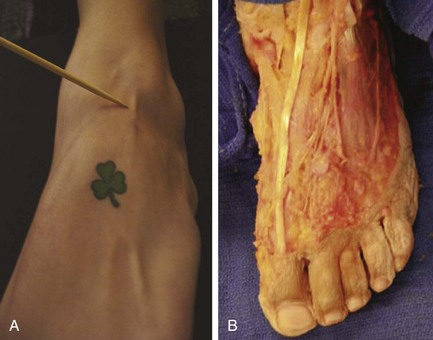

Chapter 2 Third, the human foot and ankle should be viewed as relatively recent evolutionary acquisitions; thus they are subject to considerable individual anatomic and functional variation. It is regrettable that in most of the anatomic and orthopaedic literature, only average values for the positions of axes of the major articulations and for ranges of motion about these axes are given (see Chapter 1). It so happens that an average person is difficult to find, particularly among patients seeking help in our offices. The examiner should be aware of these variations and should also be cognizant of their functional implications. In most patients, the luxury of a “normal” contralateral extremity allows the examiner the most definitive pertinent comparison. Only with such knowledge and insight can the examiner determine the proper therapeutic course and realistically evaluate the chances of success or failure of that choice. The examination of the osteology of the lateral ankle begins with the easily palpable tip of the fibula (Fig. 2-1). From the tip, the distal fibula (A) and the shaft (B) can be felt in its entirety by running the examiner’s fingers proximally. The lateral gutter of the ankle joint (C) can be found by running the thumb medially over the anterior and medial edge of the fibula. The lateral shoulder of the talus can be felt at the joint line by dorsiflexing and plantar flexing the ankle. The distal syndesmosis (D) is felt by following the medial edge of the fibula superior to the joint line. The lateral wall of the calcaneus (E) can be palpated with little difficulty inferior and posterior to the tip of the fibula. If this lateral wall is palpated distal and inferior to the tip of the fibula, the peroneal tubercle (F) can be felt as the calcaneal neck nears the calcaneocuboid joint. The sinus tarsi (G) (the space in front of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint) is a palpable soft spot approximately 1 cm distal and 1 cm inferior to the tip of the fibula. The anterior portion of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint can be located with deep thumb palpation into the sinus tarsi. The lateral talar process (H) is palpated on the posterior wall of the sinus tarsi. The anterior process of the calcaneus is the anterior wall of the sinus tarsi. The nervous topography in this region is fairly straightforward. The sural nerve can be felt in the fatty soft spot directly posterior to the peroneal tendons running in the fibular groove (Fig. 2-2). In a thin patient, this nerve can be rolled under a finger, just posterior to the course of the peroneal tendons as the tendons enter the lateral midfoot. The superficial peroneal nerve can first be palpated as a number of branches just superior to the distal ankle syndesmosis. Again, it is best seen and palpated by rolling the branch under a finger as the ankle is plantar flexed. The topography of the medial ankle and hindfoot (Fig. 2-3) is as accessible as the lateral. The reference point here is the tip of the medial malleolus (A), which also allows a reference for medial ankle osteology. The tip of the malleolus is the most distal bony prominence palpated on the medial tibia. From this point, the anterior medial tibiotalar joint line (B) can be located by sliding a thumb 2 cm superior and then lateral until the thumb feels a soft spot. This is the medial gutter, the articular space between the medial malleolus and the medial talar body. Following the gutter proximally allows palpation of the anterior distal tibial plafond. This can be followed laterally across the joint. Following the malleolus posteriorly and proximally allows palpation of the entire posterior medial edge of the malleolus and tibia. The flexor digitorum longus (FDL) (H) is easily palpated posterior and medial to the posterior tibialis tendon at a level 1 to 2 cm from the tip of the malleolus. It can be felt again in the midfoot as it crosses deep to the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon. The FHL tendon (I) is best palpated in the ankle slightly posterior and deep to the posterior tibial artery and nerve at the level 1 to 2 cm proximal to the medial malleolus. The FHL also can be felt as it passes plantar to the sustentaculum tali. The superomedial aspect of the spring ligament (superomedial calcaneonavicular ligament) is palpated plantar and deep to the posterior tibial tendon, just proximal to the tendon’s insertion on the plantar-medial navicular (Fig. 2-4). It is import to locate the neurovascular structures of the medial ankle. The pulse of the posterior tibial artery (see J in Fig. 2-3) can be felt 1 to 2 cm posterior and medial to the medial edge of the medial malleolus. The pulse is strongest approximately 2 cm posterior to the malleolar tip (Fig. 2-5). The posterior tibial nerve runs with the artery in the tarsal tunnel. The nerve bifurcates into the medial and lateral plantar nerves at the level of the tip of the malleolus. The medial branch courses distally and plantarly and can be palpated as it runs under the abductor hallucis muscle at the level of the medial gutter of the ankle joint (Fig. 2-6). The lateral plantar nerve travels straight inferior from the tarsal tunnel and can be palpated as it runs deep to the abductor hallucis. The saphenous nerve can sometimes be palpated on the medial malleolus by rolling it gently under the fingers. The Achilles tendon (Fig. 2-7A) defines the posterior ankle and hindfoot. This large tendon can best be examined with the patient prone. The tendon transects the posterior ankle and can be easily palpated because of the tendon’s subcutaneous course. The tendon inserts into the calcaneus broadly, and the Achilles insertional ridge of the calcaneus (B) is palpated at the distal insertion of the tendon. The posterior calcaneus is palpated medially, laterally, and posteriorly. The retrocalcaneal space (C), which is deep to the Achilles at its insertion, can be easily pinched by pressure from either medial or lateral. The space or its bursa (or both) is an area that is easily delineated from the Achilles proper. The posterior lateral ankle is another access point for the peroneal tendons (D) as they pass posterior to the fibula and can be an easier way to feel both tendons in the fibular groove. The same can be said for the FHL tendon (E), which is a posteromedial ankle tendon at this point (Fig. 2-8). The anterior ankle (Fig. 2-9) is defined by the readily palpable anterior tibialis tendon (A). The tendon is found by asking the patient to actively dorsiflex the ankle. The anterior tibialis, first felt at or near the midanterior ankle just proximal to the malleoli, is the largest tendon structure that passes more medially as it travels distally. Its insertion on the plantar medial cuneiform and plantar first metatarsal is defined with the same dorsiflexion maneuver (Fig. 2-10). On either side of the anterior tibialis tendon, the anterior ankle joint (B) can be felt by deep palpation. The distinction between the tibia and the talus is more easily felt with gentle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of the ankle joint. The transition from anterior tibia to anterior fibula is quite superficial and can help guide the estimation of the location of the less superficial midanterior tibia and talus. The branches of the superficial peroneal nerve (C) are palpated by gently rolling the fingers over the superficial portions of the anterior ankle (Fig. 2-11). All of these branches are found lateral to the anterior tibialis. The pulse of the dorsalis pedis artery is usually felt not at the ankle but in the dorsal midfoot. The remaining tendons of the anterior ankle (see Fig. 2-9) are all found lateral to the anterior tibialis. From medial to lateral, these easily palpable tendons are the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) (D), the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) (E), and the peroneus tertius (F) (found in most people). The examination of these tendons can be made easier by active dorsiflexion or passive plantar flexion of the toes and ankle. Medial to the anterior tibialis, no tendons are normally present. Examination of the plantar-lateral aspect of the hindfoot is all about defining the anatomy of the lateral calcaneal area (Fig. 2-12). If the examiner begins at the posteriormost aspect of the calcaneus and runs a finger distal to it, the lateral edge of the calcaneus can be felt as separate from the lateral aspect of the plantar fat pad (Fig. 2-13). The fat pad begins to be prominent as the skin texture changes from thin to thick as the weight-bearing surface of the heel becomes apparent. On the plantar surface (see Fig. 2-12), the lateral band of the plantar fascia and the abductor digiti minimi (A) are most often indistinguishable as a pinchable band originating from the palpable lateral calcaneus and extending distal to the fifth metatarsal head. The sural nerve can be felt as a cord just plantar to the peroneal tendons as they run along the calcaneal wall. The structures of the dorsal midfoot, in most cases, can be appreciated with a careful examination (Fig. 2-14A and B). The bones of the midfoot can all be palpated most readily on the dorsum. The osteology of the dorsal midfoot is best felt by starting proximal at the talonavicular joint (A). The detail of the bony edges can be defined by the palpable joints. The talonavicular joint can be felt as the most mobile joint on the medial side. By moving the foot into abduction and supination, the mobility of the joint can be felt. Whereas some motion is present in the more distal joints, in the normal foot, the talonavicular joint is most mobile.

Principles of the Physical Examination of the Foot and Ankle

Overview

Topographic Anatomy

Ankle and Hindfoot

Lateral Ankle

Medial Ankle

Posterior Ankle

Anterior Ankle

Plantar Hindfoot

Midfoot

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Principles of the Physical Examination of the Foot and Ankle