Primary Total Knee: Standard Principles and Technique

Paul A. Lotke

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

A total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is indicated for severe disability resulting from pain, deformity or limited function as a result of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or any other type of arthritic deformity around the joint. Surgery should be considered only after adequate trials of conservative therapy, including anti-inflammatory medications and modifications in daily activities. In addition, both pain and deformity should be present. Pain alone should make the physician look for other diagnoses and treatment alternatives. Structural deformities without significant pain or disability may be well tolerated, especially in the elderly, and should not alone be an indication for surgery. The patient should also have realistic goals. A well-placed total knee will neither feel nor function like a normal knee. Younger patients should be advised about overuse and activity leading to failure or pain. Older patients should realize that reconstructing the joint alone will not alter their overall functional abilities. When the disease involves a single compartment, other surgical alternatives should be considered. A unicompartmental arthroplasty can offer excellent results, less bone loss, and lower morbidity then a TKA. This procedure is especially useful for younger patients with unicompartmental disease who engage in high-level activities.

When there is deformity in both knees, arthroplasty may be performed in either one or two stages. If both knees are operated on at the same stage, we must compensate for the blood loss. The amount

of blood loss is frequently unrecognized and underestimated. In the elderly, acute lowering of the red cell mass is not well tolerated and can lead to medical problems.

of blood loss is frequently unrecognized and underestimated. In the elderly, acute lowering of the red cell mass is not well tolerated and can lead to medical problems.

There are relatively few contraindications of TKA and include inactive or latent infection. The relative contraindications include Charcot joint, poor skin coverage, and ankylosis. Although it sounds simplistic, a good history and examination are the most effective ways to ensure that the patient meets the criteria and recommendations for a TKA. Once it is established that the patient is a satisfactory candidate for a TKA, the specific details of the procedure can be addressed.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

The standing anterior posterior (AP) radiograph is usually the most important study for evaluating the preoperative status of the knee. However, lateral and patella views are also relevant in assessing the preoperative knee. Some surgeons consider having a full-length radiograph taken from hip to ankle. However, without a history of prior trauma, I do not routinely obtain a full-length film and feel that most of the necessary information can be obtained on a 17-inch cassette. If the patient has a history of surgical procedures or trauma to the hip or lower leg, he or she should have a radiograph taken of that site to rule out unrecognized bone pathology. The standing AP radiograph will allow us to determine joint space, bone loss requiring augmentation, ligamentous laxity, and alignment. In addition, observations are made as to the size and position of the osteophytes that should be removed to reconstruct the anatomical contours of the knee and avoid impingement.

The lateral and patella views are also important for preoperative planning. The patella view will show if there are erosive changes, thinning, or subluxation of the patella. The lateral radiographs are important assessments for patella baja, which may occur from previous surgery, osteotomy, or arthroscopic procedures. In addition, we can assess if the posterior compartment of the knee contains large osteophytes that require removal during the surgical procedure.

The preoperative examination should document the condition of the skin and the location of previous scars. Any prior incision or scar is important, especially if parallel to your planned arthrotomy. Every effort should be made to incorporate the old scar into the new incision. In general, if two scars are present, I choose the longer of two scars and extend it as necessary. Parallel incisions should be assiduously avoided. The presence of psoriasis should be noted. This is not a contraindication for surgery, but the skin condition should be optimized before surgery.

SURGERY

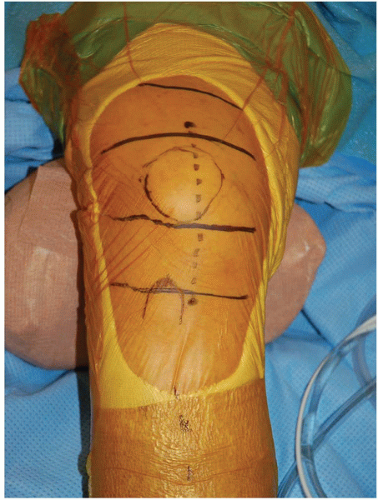

Arthrotomy

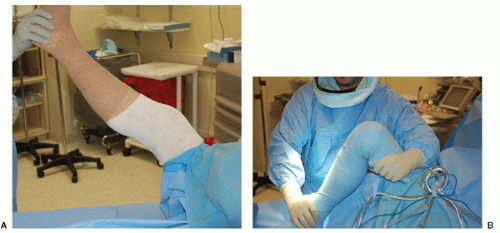

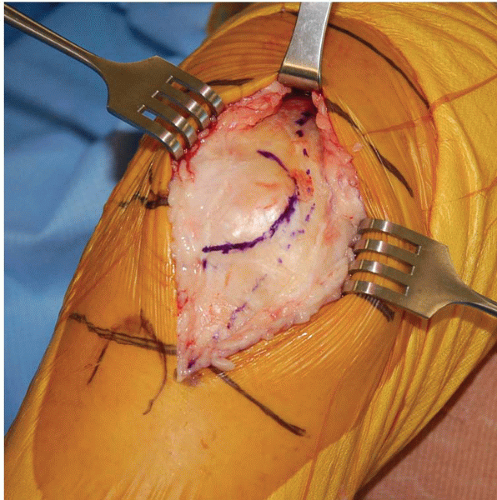

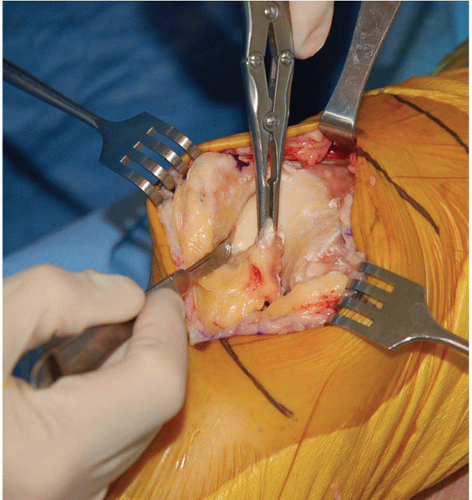

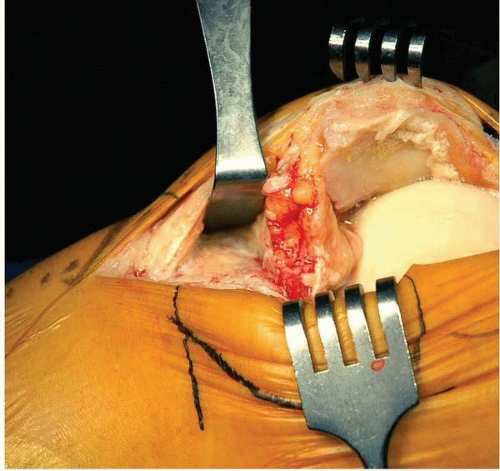

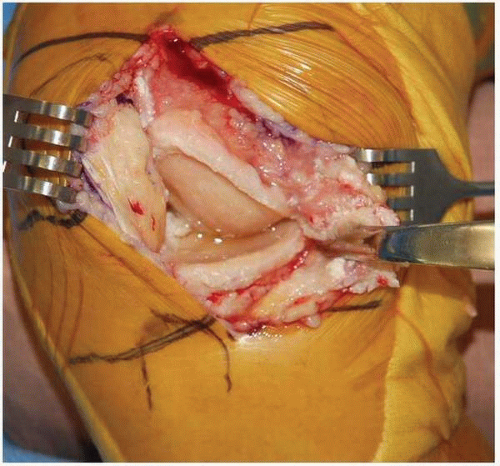

The patient is placed in the supine position and carefully prepped and draped. I fold a cuff into the sterile drape, under the thigh, so that the drapes will not be disturbed or restrictive when I move or flex the knee (Fig. 5-1A,B). I use an anterior medial incision of approximately 12 to 15 cm. It may begin 3 cm above the patella and end 1 cm below the top of the tibial tubercle (Fig. 5-2). The length of the incision is not important as long as it allows adequate exposure to perform the procedure efficiently and safely. Proximally, the margins of the quadriceps tendon are identified with a right angle retractor slid on the quadriceps tendon and beneath Scarpa’s fascia. I make a median parapatellar incision, which is extensile and can be extended, if necessary, in obese, muscular, or stiff joints. (Fig. 5-3). The knee joint is entered and briefly inspected. Some of the fat pad is removed (Fig. 5-4). The surgeon enters the bursa below the retroperitoneal fat pad and incises the anterior lateral capsule (Fig. 5-5). Medially, the soft tissue sleeve is dissected from the proximal medial tibial metaphysic, on top of the periosteum, and follows within the natural plane of the pes anserinus bursa (Fig. 5-6). This dissection is extended back to the posterior corner of the knee. The only structure that requires sharp dissection in this plane is the meniscal tibial ligament. The edge of the medial soft tissue sleeve is kept intact so that a watertight closure can be obtained at the end of surgery. With this approach into the knee, the blood supply in the periosteum on the anterior and medial side of the tibia is essentially left undisturbed.

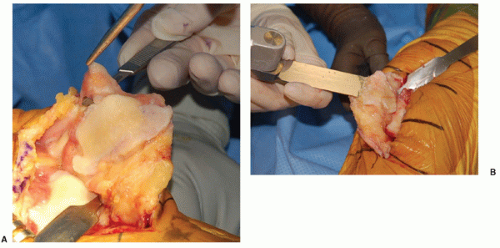

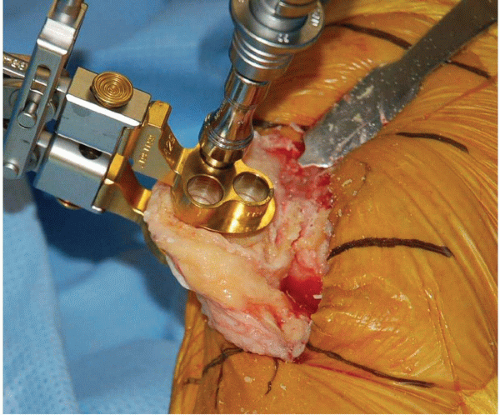

The knee is extended, and the patella is everted in extension. With a Lahey clamp holding the eversion, and a Homan retractor stabilizing the patella, the retropatellar osteotomy is carried out (Figs. 5-7A,B, 5-8, and 5-9).

The knee is then flexed, and the surgeon excises the anterior cruciate ligament. If the surgeon is preserving the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), it should be left undisturbed. I release the lateral meniscus and place a Homan retractor under the meniscus retracting the meniscus and extensor mechanism laterally. The patella is not everted, as it is not necessary for good exposure of the knee. With flexion, external rotation, and anterior displacement, the tibia can be subluxed forward, and excellent exposure of the tibial plateau and femoral condyles can be obtained (Fig. 5-10). If there is too much tension on the skin, I lengthen the incision as needed.

FIGURE 5-2 The incision starts just proximal to the patella and extends 1 cm below the medial side of the tibial tubercle. It may measure 12 to 15 cm but can be extended if needed. |

FIGURE 5-5 A right angle retractor slides within the bursa, under the remaining fat pad, and exposes the anterior and lateral aspects of the tibia without cutting a vessel. |

FIGURE 5-6 The medial sleeve is developed on the periosteum and within the pes anserinus bursa. Again, no vessel needs to be cut in this plane, and the bursa is preserved. |

FIGURE 5-8 The thickness of the patella can be measured before and after the osteotomy. As the surgeon gains experience, this step becomes less essential. |

Bone Cuts

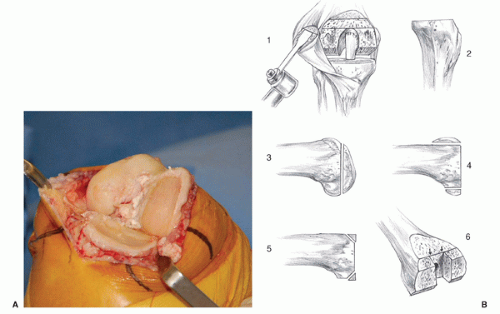

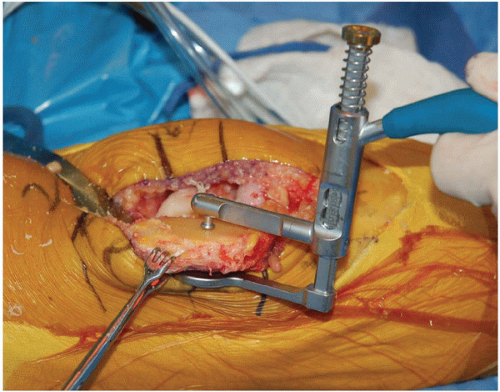

In the total knee procedure, the surgeon uses the same five bone cuts whether the prosthesis is cemented in place, fixed with porous ingrowth, and/or if the PCL is saved or preserved (Fig. 10B). The only difference is the sixth step for removing the intercondylar notch for posterior cruciate-substituting prosthesis. These essential bone cuts are made regardless of the amount of bone loss, ligament imbalance, or osteophytes present around the joint. For a routine TKA, I perform a measured resection technique in which the osteotomies are calculated to reproduce the joint lines with the thickness of the metal prosthesis. I will make the bone cuts, remove all osteophytes, and then evaluate and compensate for any soft tissue imbalance. In general, after the osteophytes are removed and normal anatomic boundaries have been re-established, no specific releases or additional balancing is necessary. For knees with severe deformities, or when soft tissue imbalances are a major problem, however, only then soft tissue releases are considered (see Chapter 7).

The five essential cuts for any TKA are as follows (Fig. 5-10B):

Retropatellar osteotomy

Transverse osteotomy of the proximal tibia

Resection of distal femoral condyles angulated 4 to 6 degrees of valgus alignment

Anterior and posterior condylar resections to accept prostheses of the appropriate size and rotated to make equal flexion gaps medially and laterally

Chamfers from the distal femur anteriorly and posteriorly to conform to the internal prosthetic configuration

(This cut is optional.) Resection of the intracondylar notch for a posterior cruciate-substituting prosthesis

Patellar Osteotomy

The retroperitoneal osteotomy is completed early in the case with the knee in extension (Fig. 5-7). This debulks the patella and allows it to be subluxed without eversion and reduces the tension on the tibial tubercle. It almost eliminates the risk of patellar tendon peel from the tubercle. I try to reproduce the native thickness of the patella with 10 to 15 mm of patella remaining. A caliper can be used

to determine the thickness of the patella before and after the osteotomy (Fig. 5-8), however, with experience, this becomes less necessary. There are clamps that can be used to guide in this retroperitoneal osteotomy. Again, with experience, the guides become less necessary. The synovial/fat soft tissue mass at the superior pole of the patella should be excised to avoid a postoperative “clunk syndrome” (Fig. 5-7A). After the osteotomy has been completed, drill holes can be placed into the retroperitoneal surface to accept the patellar button (Fig. 5-9). I generally use a patellar button in my total knee replacements.

to determine the thickness of the patella before and after the osteotomy (Fig. 5-8), however, with experience, this becomes less necessary. There are clamps that can be used to guide in this retroperitoneal osteotomy. Again, with experience, the guides become less necessary. The synovial/fat soft tissue mass at the superior pole of the patella should be excised to avoid a postoperative “clunk syndrome” (Fig. 5-7A). After the osteotomy has been completed, drill holes can be placed into the retroperitoneal surface to accept the patellar button (Fig. 5-9). I generally use a patellar button in my total knee replacements.

Osteotomy of the Proximal Tibia

The femoral and tibial osteotomies are independent of each other, so either may be performed first. I recommend that the tibia be osteotomized first, however, to accurately determine the femoral rotation and establish equal medial and lateral gaps in flexion by tension. Rarely, if the knee is tight or if good exposure is difficult to obtain, will I osteotomize the femoral condyles first.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree