Primary Care for Persons with Disability

William L. Bockenek

Gerben DeJong

Indira S. Lanig

Michael Friedland

Amanda Harrington

The issue of providing quality medical care to all persons has been brought to the forefront with the current changes in medicine and health care reform. Terms such as “cost containment,” “appropriate utilization of resources,” and “quality management” are heard by practicing physicians on a daily basis in reference to their patient care interactions. The impetus to make changes in our current health care system has also been influenced by economic issues (1). Health care costs have increased exponentially in recent years, and even though these costs have risen significantly, patients’ health outcome and satisfaction have not risen proportionately. When the United States was compared with numerous other countries with respect to health outcomes and satisfaction in relation to cost, the United States ranked lowest of the nations studied, compared with countries such as The Netherlands, which was among the best (1). When the same countries were compared with respect to their percentage of primary care physicians, the results were similar, with the United States having the smallest percentage of primary care physicians and the countries with greatest satisfaction having the greatest percentage of primary care physicians. When the cost factor is eliminated, however, health care quality in the United States is among the finest in the world. Unfortunately, it is not accessible and available to all. Because of lack of income, lack of insurance, isolation, language, culture, or physical disability, millions still face barriers to quality health care.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has seven strategic goals that support its mission. They are as follows:

Improve Access to Health Care

Improve Health Outcomes

Improve the Quality of Health Care

Eliminate Health Disparities

Improve the Public Health and Health Care Systems

Enhance the Ability of the Health Care System to Respond to Public Health

Emergencies

Achieve Excellence in Management

The 2008 budget for this organization approximates $5.8 billion, some of which is allotted to those with disabilities. The Bureau of Primary Health Care within the Health Resources Service Administration is allotted $1.98 billion for 2008 (2).

Although there is general consensus in the United States and abroad that primary care is a critical component of any health care system, there is considerable imbalance between primary and specialty care in the United States (3). The proportion of specialists in the United States is more than 70% of all patient care physicians, whereas in other industrialized countries, 25% to 50% of physicians are specialists (3). There are multiple factors and forces that have led to the dissatisfaction with primary care fields. Medical students are choosing non—primary care specialties at a greater rate each year. The percentage of U.S. medical graduates choosing family medicine decreased from 14% in 2000 to 8% in 2005 (4). Issues such as noncompetitive income, excessive/unpredictable work hours, and concerns about patient outcomes due to shorter and more rushed office visits have also led to 75% of internal medicine residents eventually choosing to be subspecialists or hospitalists, rather than general internists (4).

Further work has shown that based on staffing patterns in classic health maintenance organizations (HMOs), there are about 3.1 times more pathologists, 2.5 times more neurosurgeons, 2.4 times more general surgeons, 2.0 times more cardiologists and neurologists, 1.9 times more gastroenterologists, 1.8 times more ophthalmologists, and 1.5 times more radiologists in the nation than would be needed (3). Although it is clear that there is a plethora of specialists and a need for greater primary care services, considerable room for debate remains on its true impact on health care costs and quality of patient care.

Beginning in the late 1980s and continuing to the present, recognition of the difficulties that persons with disabilities face in accessing quality health care has become apparent. Persons with disabilities represent approximately 10% of the world’s population, yet they are among the most underserved groups (5). Although the medical literature is relatively sparse on this issue, multiple conferences and publications have addressed this topic. The Association of Academic Physiatrists and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation have both previously developed position statements on the provision of primary care services to persons with disabilities, lending their support to physiatrists who choose to provide these services; however, there are a variety of opinions among practitioners as to how these services are best provided (6,7).

This chapter provides an overview of the primary care issue, with special emphasis on persons with disabilities, as well as a discussion of issues on health promotion in this

population. A practical approach to primary medical care in a general population that can easily be adapted to persons with disabilities follows. The chapter concludes with a review of several models of primary care and describes management issues more specific to those with disabilities.

population. A practical approach to primary medical care in a general population that can easily be adapted to persons with disabilities follows. The chapter concludes with a review of several models of primary care and describes management issues more specific to those with disabilities.

DEFINITIONS OF PRIMARY CARE

The HRSA has defined primary care based on the following three anchoring principles: (a) the routine medical care and services people receive on first contact with the health care system for a particular health incident, that is, prevention, maintenance, diagnosis, limited treatment, management of chronic problems, and referral; (b) assumption of longitudinal responsibility for the patient regardless of the presence or absence of disease (i.e., all of a person’s health care needs—physical, psychological, and social—are met); and (c) integration of other health resources when necessary (gatekeeper function) (8).

The Institute of Medicine (9) has provided a definition as well, which states that primary care is the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community. “Integration” includes comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous services. “Accessibility” refers to eliminating geographic, financial, and cultural barriers to seeing the caregiver. “Health care services” includes hospitals, nursing homes, office, school, home, and intermediate care facilities. “Clinicians” can be physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or similar health care practitioners. “Accountable” refers to the clinician being responsible for quality of care, patient satisfaction, efficient use of resources, and ethical behavior. “Majority of personal health care needs” describes the full spectrum of physical, mental, emotional, and social concerns. “Sustained partnership” is a long-term relationship that includes health promotion, disease prevention, and the management of disease itself. “Context of family and community” includes an understanding of the patient’s social background and support systems.

Another approach at defining primary care is from the patient’s perspective (10). A primary care physician is a trusted physician who (a) performs all preventive care necessary to safeguard health, (b) diagnoses and treats self-limiting conditions, (c) diagnoses serious conditions and either treats those for which he or she has expertise or refers the patient to the best available expert for treatment. A strength of this functional patient-oriented definition is that it delineates the three tiers of health care provided by all primary care physicians.

Primary care may be distinguished from specialty care by the time, focus, and scope of services provided to the patients (3). Primary care as noted above is first-contact care on entry into the health care system. Specialty care generally follows primary care upon referral from the primary care provider. Whereas primary care addresses the person as a whole, specialty care usually focuses on specific diseases or organ systems. Because primary care providers see patients at their initial interface with the health care system, they are presented with a variety of symptoms and concerns that may represent early stages of disease that are not yet easily classified into specific diseases or organ systems. Through the various roles of the primary care provider, but especially the gatekeeper function, referral to specialty care occurs when organ- or diagnostic-specific disease is identified that is beyond the scope of services provided by the primary care provider. Although primary care is comprehensive in scope and is present throughout the continuum of care, specialty care tends to be limited to specific illness episodes, the organ system involved, or the disease process identified.

PRIMARY CARE ISSUES IN GRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION

Three specialties typically are thought of as primary care fields. The largest is general internal medicine, followed by general pediatrics and family practice. Obstetrics and gynecology, although regarded by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the American Medical Association as a primary care provider for women, does not traditionally fulfill this role because it does not meet the “whole body” medicine criterion often cited as the standard for judging whether a specialty offers primary care (11). Nevertheless, it is clear that many women consider their gynecologist to be their primary care provider (12).

In its third report (13), the Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME) stated that generalist physicians are trained, practice, and receive continuing education in a broad set of competencies to care for the entire population in office, hospital, and residential settings; provide comprehensive age- and sex-specific preventive care; evaluate and diagnose common symptoms; treat common acute conditions; provide ongoing care for chronic illnesses and behavior problems; and seek appropriate consultation for other needed specialized services. Given these required competencies, COGME concluded that family physicians, general internists, and general pediatricians are properly trained to function as generalist physicians. Although other physicians provide elements of primary care, COGME also noted that physicians who are broadly educated as generalist physicians provide more comprehensive and cost-effective care than do other specialists and subspecialists (14).

The recent emphasis on health care system reform has sparked the decades-old debate as to who is a generalist physician and has reemerged with important implications for physician workforce policy and medical education (14). In its third report (13), COGME recommended that the nation set a goal that at least 50% of all physicians be practicing generalist physicians. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommended that a majority of graduating medical students be committed to generalist careers (15). Both COGME and

the AAMC define generalist physicians as residents who complete a 3-year training program in family medicine, internal medicine, or pediatrics and who do not subspecialize. Given the enhanced role and growing prestige of the generalist physician and the increased emphasis on primary care, other physician groups, including physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R), have suggested that they be included in this category (6,14). In its fourth report (16), COGME stated that the designation of a specialty being included as primary care should be based on an objective analysis of training requirements in disciplines that provide graduates with broad capabilities for primary care practice. In an analysis of the training requirements of numerous specialties, including those typically thought of as primary care specialties (family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics) and several that have proposed inclusion as a primary care specialty (emergency medicine and obstetrics and gynecology), only the previously established primary care fields actually prepared their residents in the broad competencies required for primary care practice (14). Although PM&R was not included in the analysis, based on the current training requirements and a similar analysis, it would not fulfill the necessary training needs.

the AAMC define generalist physicians as residents who complete a 3-year training program in family medicine, internal medicine, or pediatrics and who do not subspecialize. Given the enhanced role and growing prestige of the generalist physician and the increased emphasis on primary care, other physician groups, including physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R), have suggested that they be included in this category (6,14). In its fourth report (16), COGME stated that the designation of a specialty being included as primary care should be based on an objective analysis of training requirements in disciplines that provide graduates with broad capabilities for primary care practice. In an analysis of the training requirements of numerous specialties, including those typically thought of as primary care specialties (family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics) and several that have proposed inclusion as a primary care specialty (emergency medicine and obstetrics and gynecology), only the previously established primary care fields actually prepared their residents in the broad competencies required for primary care practice (14). Although PM&R was not included in the analysis, based on the current training requirements and a similar analysis, it would not fulfill the necessary training needs.

The ability to provide effective primary care or appropriate treatment for life-threatening illnesses not only depends on adequate training but a continued interest in the area of concern, as well as continued experience based on an appropriate number of cases (10). The growing quality agenda and the move toward mandatory Maintenance of Certification by the American Board of Medical Specialties (and Maintenance of Licensure by the Federation of State Medical Boards) shed additional light on the increasing requirements to maintain expertise in primary care activities. It is not enough to be adequately trained during residency in specific aspects of primary care or the treatment of a serious disease or high-risk procedure because this training quickly becomes outdated in the face of the rapid advances in clinical medicine. The individual choosing to be a primary care provider needs to remain current in the management of any condition that is diagnosed and is needing treatment (10).

In its eighth report (17), COGME evaluated five models that attempted to determine projections for the number of physicians needed for the current century. The differences in the five models lie in the degree to which historic increases in the demand for specialists are assumed to continue in the increasingly competitive managed care setting. COGME hypothesized that market forces will at least balance increasing demand for specialty services resulting from new technology. Consequently, increasing demand for specialists was not as anticipated. The ultimate requirement for generalists and specialists will depend on the configuration of future health care systems. COGME anticipated increased utilization of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, both in specialty care and in primary care. The overall trend, however, was felt to be an increased emphasis on generalists within managed systems of care, thus reducing the demand for specialists.

GENERALIST VERSUS SPECIALIST

Although it is well accepted that there is an imbalance between primary and specialty care, numerous arguments have been advanced by advocates of both the generalist and specialist perspectives (3,13,18). The generalist perspective points to the research that supports the efficacy of primary care and indicates that generalists have broader medical knowledge and skills; are better trained in psychosocial, preventive, and community aspects of care; and provide less costly care and are more accessible, factors that make them preferable to specialists as primary care providers (18). In addition, the generalists’ cross-disciplinary skills provide for more efficient referral patterns when using their gatekeeper function.

Specialists, on the other hand, assert that their training before subspecialization is equivalent to generalists, allowing them to deal with primary care issues (similar to generalists) as well as manage problems within their specialty (that generalists might have to refer elsewhere) (18). Numerous studies support the specialist viewpoint that primary care can be provided in an efficient and cost-effective manner by the same practitioner who provides more sophisticated, specialized, and up-to-date medical services (18).

MEETING THE POSTREHABILITATION HEALTH CARE NEEDS OF PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

The traditional distinctions between primary care and specialty care become much less clear when we consider the ongoing postrehabilitative health care needs of people with disabilities (11). Here, the boundaries between primary and specialty care overlap considerably. It is not clear where one ends and the other begins. The handoff from rehabilitative care in the rehabilitation center to primary care in the community is not straightforward. This is best understood when we consider the nature of the ongoing health care needs of people with disabilities and why many primary care issues have significant rehabilitative or functional content.

It is difficult to generalize about the ongoing health care needs of people with disabilities, in part, because different disabling conditions have widely varying pathophysiologies, comorbidities, and functional consequences. These differences often obscure the fact that people with disabilities experience most of the same health conditions experienced by people without disabilities. However, people with disabilities are at greater risk for certain common health conditions than are those in the general population, often experience these conditions differently, and may require a somewhat different and extended therapeutic regimen that takes into account both their underlying impairment and their functional limitations. However, people with disabilities observe that many health care providers are often unable to look beyond the disabling condition to address the health problem that precipitated the provider-patient encounter in the first place.

SIX CHARACTERIZATIONS

There are many ways one can characterize the ongoing health care needs of people with disabilities relative to those without disabilities. At the risk of overgeneralization, we note six ways in which the ongoing health care needs of people with disabilities are different from those in the general population. These characterizations are limited mainly to people with the types of conditions commonly seen in inpatient rehabilitation settings (19,20).

First, people with disabilities generally have a thinner margin of health that must be carefully guarded if medical problems are to be averted (21). This observation applies to health conditions that people with disabilities share with the nondisabled population (e.g., upper respiratory infection, pneumonia) as well as conditions more likely to appear among people with disabling conditions (e.g., urinary tract infections, renal failure, pressure sores). It should be emphasized that people with disabilities are not “sick” and that most are generally very healthy. However, their impairments and functional limitations often render them more vulnerable to certain health problems.

Second, people with disabilities often do not have the same opportunities for health maintenance and preventive health as those without disabilities. For example, people with mobility limitations usually have fewer opportunities to participate in aerobic activity needed for good cardiovascular health, and people with paralysis may not be able to detect certain health conditions early because they cannot experience pain in certain body regions (21).

Third, people with disabilities who acquired their impairment early in life may experience onset of chronic health conditions earlier than people in the general population. For example, it is believed that people with long-standing mobility limitations are likely to have an earlier onset of coronary artery disease than the general population. Likewise, people with mobility limitations may experience an earlier onset of adult diabetes because of obesity and may experience an earlier onset of renal disease (e.g., pyelonephritis) because of a neurogenic bladder dysfunction (22).

Fourth, people with disabilities who acquire a new health condition, apart from their original impairment, are likely to experience secondary functional losses. Thus, the functional consequences of a new chronic health condition are usually more significant for a person who already has a disabling impairment. The onset of exertional angina or a rotator cuff injury, for example, may require that the person upgrade from a manual to an electric wheelchair and from a conventional automobile to an adapted van.

Fifth, people with disabilities may require more complicated and prolonged treatment for a given health problem than do people without disabilities. For example, using a plaster cast for a broken leg may be complicated by the individual’s vulnerability to a pressure sore when the individual has no sensation in the lower limbs. Likewise, a person with a disability may require a longer recovery period after an acute episode of illness or injury because of preexisting functional limitations that limit a person’s participation in various therapies (e.g., using a treadmill or exercise bicycle after an acute myocardial infarct).

And sixth, people with disabilities may need durable medical equipment and other assistive technologies that require some level of functional assessment. Today, these devices are often prescribed by physicians who have only a rudimentary understanding about the fit between various types of equipment and the needs of the individual consumer. A poor fit between the individual and an assistive device can reduce functional capacity and may induce the individual to abandon the device, the combination of which is wasteful for both the individual and society.

These six characterizations are not exhaustive. A more complete characterization will be important in sorting out the respective roles of traditional primary care disciplines and the various specialty disciplines in managing the health care needs of people with disabilities. The six characterizations point out that traditional distinctions lose their meaning when managing the health care needs of a person with a disabling or chronic health condition.

IMPACT ON HEALTH CARE UTILIZATION AND EXPENDITURES

These six characterizations are borne out in the above-average rates of health care utilization and expenditures among people with disabilities. The 2005 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) provides a broad overview of the health care utilization and expenditure experience of adults with selected functional limitations. Using variables available in the MEPS, we considered persons as having a disability if they meet any one of the following criteria: (a) use mobility aids or equipment,

(b) are limited in major activity (work or housework only), or

(c) require help or supervision with at least one activity of daily living (ADL) or instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) (i.e., essential tasks for maintaining ones living environment and residing in the community) (23).

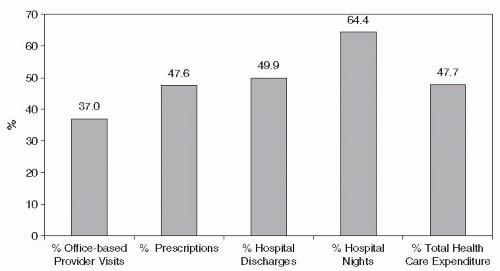

Using this definition of disability, individuals with disabilities comprise 15.9% of the adult population (age 18+). Yet, in 2005, they accounted for 37.0% of all physician visits made by adults, 47.6% of all adult prescriptions (including refills), half of all hospital discharges, 64.4% of all nights spent in the hospital by adults, and 47.7% of all adult-related health care expenditures (Fig. 60-1).

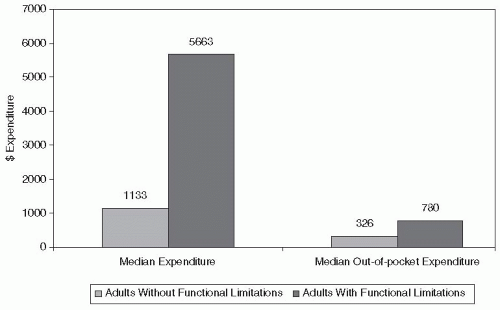

The disproportions reported above are also reflected in estimates of the utilization and expenditure experience of individual adults with disabilities. While only 3.4% of adults with disabilities had no health care expenditures in 2005, 23.6% of individuals without disabilities had no health care expenditures. Of those with at least $1 expenditure, the median expenditure for people with disabilities was $5,663, compared to $1,133 for people without disabilities. These figures represent more than a doubling over a 9-year period. Adults with

disabilities also typically pay more out of their own pocket ($780) for health care than the nondisabled expenditure paid from all sources ($326) (Fig. 60-2). (Median total and out-of-pocket expenditures are calculated only for those who had at least a $1 total or $1 out-of-pocket expenditure, respectively. Of note, out-of-pocket expenditures do not include health plan premiums.)

disabilities also typically pay more out of their own pocket ($780) for health care than the nondisabled expenditure paid from all sources ($326) (Fig. 60-2). (Median total and out-of-pocket expenditures are calculated only for those who had at least a $1 total or $1 out-of-pocket expenditure, respectively. Of note, out-of-pocket expenditures do not include health plan premiums.)

ACCESS TO PRIMARY CARE

Over 80% of disabled persons have at least one secondary medical condition (24). Many of the secondary health conditions experienced by people with disabilities, however, are entirely preventable through scrupulous health maintenance strategies and timely interventions by knowledgeable practitioners before new health conditions become emergent or even life threatening (23,25,26).

People with disabilities often express frustration about the barriers that limit their access to primary care. These barriers can be grouped into (a) process barriers and (b) structural-environmental barriers (27).

Process barriers refer mainly to the communication, attitudinal, and knowledge barriers in the provider-patient relationship (27). Persons with disabilities often describe their providers as not being knowledgeable about the management of secondary health conditions and the impact of these conditions on their functional capacities (21,28, 29, 30). They remark that they must make considerable effort to educate their primary care providers about their disability and how it needs to be taken into consideration when new health conditions are addressed (31). In other instances, a provider may have difficulty looking past the disabling impairment to also consider the primary and preventive care needs of a patient with a disability. Nearly two decades of studies have made the same observations. In a 1989 survey of 607 respondents with

disabilities (e.g., spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, postpolio) in the Washington, DC area—a seemingly dated study, researchers found that many people had difficulty finding a physician who was knowledgeable about their health care needs (32). Respondents who had a previous rehabilitation experience often indicated that they consulted with their original physiatrist when they were not confident about a therapy recommended by their primary care physician. Subsequent smaller scale studies underscore the process and communication barriers cited by individuals with disabilities (27,33, 34, 35).

disabilities (e.g., spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, postpolio) in the Washington, DC area—a seemingly dated study, researchers found that many people had difficulty finding a physician who was knowledgeable about their health care needs (32). Respondents who had a previous rehabilitation experience often indicated that they consulted with their original physiatrist when they were not confident about a therapy recommended by their primary care physician. Subsequent smaller scale studies underscore the process and communication barriers cited by individuals with disabilities (27,33, 34, 35).

Health plans and health care providers are sometimes said to lack “disability literacy” or “disability competence,” akin to “cultural competence,” when encountering individuals with disabilities (36, 37, 38, 39, 40). The lack of “disability literacy” and “competence” occurs despite the fact that health plans and providers have considerable contact with individuals with disabilities owing to the disproportionate use of health care services by individuals with disabilities.

Structural-environment barriers include the “physical, social, and economic” environment in which primary care services are rendered (27). They include, but are not limited to, the physical layout of the physician’s office building, the medical equipment, the patient’s financial resources, and the business interests of the provider (41). Inaccessible entrances, a lack of adjustable diagnostic equipment (e.g., radiologic equipment, examining tables), narrow hallways, and inadequate parking are all reported examples that can make the primary care visit a difficult experience (42,43).

Primary care providers may prefer to serve only a very limited number of people with disabilities because people with disabilities often take longer to process in the course of an ordinary office visit and slow down a busy office practice (23,44). Primary care physicians serving patients participating in capitation-based managed care plans have even less incentive to serve high-use populations, such as individuals with disabilities.

The rise of managed care beginning in the mid-1990s and continuing into the present is commonly thought to be adverse to individuals with disabilities. Researchers report that managed care has made access to downstream services such as rehabilitation and assistive technology more difficult than under traditional fee-for-service plans (45). Yet, they also report that individuals participating in managed health care plans had a more regular source of primary care than those in fee-for-service plans but also had somewhat less choice as to who their primary care provider would be (23,46).

The persistence of these process and structural barriers is remarkable given the requirements of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and its ensuing regulatory requirements. Some requirements of the ADA may not apply to smaller private practices. Yet, the Act has heightened awareness of society’s obligation to better meet the accessibility needs of individuals with disabilities. Recent ADA-inspired litigation involving inaccessible health care facilities has failed to dramatically increase awareness in this area (47,48).

MULTIDIMENSIONAL CHARACTER OF THE ISSUES

This brief review illustrates how the boundary issues between primary and specialty care, in the case of people with disabilities, need to be addressed at several different levels. First, there is the issue of the functional and rehabilitative implications inherent in many primary care encounters. Second, there is the issue of knowledge base and whether traditional primary care providers are adequately equipped to address the needs of people with disabilities. Third, there is the issue of whether primary care providers have the facilities to accommodate people with disabilities. And fourth, there is the issue of whether our system of health care financing discourages providers, primary care or otherwise, from addressing the primary health care needs of people with disabilities.

PHYSICAL MEDICINE AND REHABILITATION AS A PRIMARY CARE SPECIALTY

With these issues in mind, the notion of PM&R as a primary care specialty can now be brought into focus. PM&R is the medical specialty that addresses the needs of severely disabled persons. Primary care physicians often refer these patients after a catastrophic illness. When these patients require comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation, the physiatrist usually serves as their primary caregiver during their relatively short hospital stay but subsequently sends patients back to the referring physician for follow-up general medical care. Follow-up visits at the physiatrist’s office typically concentrate on rehabilitation issues (11).

In contrast, patients with spinal cord and brain injuries often present from referring specialists, that is, neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons, with no regular primary care physician. After hospitalization, their follow-up care and health maintenance to prevent rehospitalization become major issues. Physicians in spinal cord and brain injury centers often choose to become the primary care physicians for these patients. Because of the specialized and often complex medical needs of the person with severe disability, primary care physicians in the community often welcome the physiatrist’s involvement and encourage his or her assistance in providing for the primary care needs of their mutual patients (11).

Primary care services are often requested, by those persons with severe disability, to be performed at the rehabilitation facility. In a survey (49) of 144 outpatients with spinal cord injury, it was found that 48% considered their rehabilitation physician as their primary care physician. Fifty-one percent of persons also requested that all of their general medical care be provided by the physicians at the rehabilitation facility. The primary reasons for these requests included maintaining continuity of care with the physician who the patients felt best understood their specialized needs, as well as easier integration with the rehabilitation hospital

for other ancillary health needs (e.g., seating clinic, physical and occupational therapies).

for other ancillary health needs (e.g., seating clinic, physical and occupational therapies).

Although it appears that many patients would like their primary care needs met by the physiatrists, there is not a clear consensus of whether this is a practical approach to the issue of providing this care. The problems described in developing PM&R as a primary care specialty were outlined partially earlier in this chapter. Additional considerations include manpower or workforce issues, the preferences professed by current practitioners in the field as well as those in training, and concerns dealing with PM&R residency curricula and the ability to provide adequate training in primary care issues based on our present residency requirements.

As previously noted, it is widely believed that there is a shortage of generalists/primary care physicians. There are several ways to reach the goals previously set forth by COGME (13,17) and the AAMC (15). They include having more medical school graduates enter primary care fields, reducing the number of specialty residency positions, and encouraging current practitioners in subspecialties to broaden the scope of their practice to include a more primary care role (50,51). An additional option is to change the current curriculum of some of our residency programs to include more training in primary care issues.

Even with the proposed paucity of generalist physicians, it was widely held in the 1990s that there would be an oversupply of physicians by the year 2000. In fact, in COGME’s fourth report (16) and eighth report (17), it was proposed that the number of federally funded entry-level positions in graduate medical education be restricted to 110% of the number in medical school in 1993 and that 50% of the graduates should be generalist physicians. Since that time, others have made alternative suggestions, including expanding the enrollment of U.S. medical schools to fulfill the shortfall between the supply of graduates of U.S. medical schools and entry-level positions in graduate medical education (52). COGME’s 16th report (53) in 2005 set a prediction of a physician shortage, with the demand for physicians being significantly outweighed by the supply by 2020. They recommended that medical schools expand the number of graduates by 3,000 per year by 2015 in order to help the predicted shortfall of 85,000 needed physicians in 2020. It was also noted that this increase will not likely meet the needs of the projected increase in demand alone; however, improvements in productivity and changes in the health care delivery system might help achieve balance.

The AAMC quickly followed COGME with their own statement on the physician workforce needs (54). The AAMC noted that between 1980 and 2005, the nation’s population grew by 70 million people (a 31% increase). As baby boomers (those born between 1943-1960) age, the number of Americans over age 65 will grow as well. Baby boomers with a disability and those who become disabled as they age are increasing as well. In general, the elderly/disabled average two to three times as many physician visits, therefore approximately 50% more visits to the doctor in 2020 than 2000. In addition, since 1980, first-year enrollees in U.S. medical schools per 100,000 population has declined annually. Physician retirees will increase from 9,000 in year 2000 to 23,000 in 2025. Also, it is evident that those recently completing residency are among a new generation that are asking for increased quality of life and fewer work hours. Consequently, America will have fewer and fewer doctor/work hours each year relative to our continually growing population (54). The AAMC called for a 30% increase in U.S. medical school enrollment by 2015. This will result in an additional 5,000 new medical physicians annually. They suggested that this could occur through a combination of enrollment increases in existing medical schools and the establishment of new U.S. medical schools. Even with these proposed increases, the AAMC predicts that there will still be a shortfall. With the current trend of medical students moving into more specialized practices (nonprimary care), as noted previously, and the shortfall of physicians being predicted, the need for an increase in primary care providers will be even greater.

In the late 1990s, a workforce study was performed to determine the current and future manpower needs for the PM&R practitioner (55). The model was based on the assumption that current residency capacity as well as utilization of physiatry skills remains constant at its 1994 to 1995 level. The results were that the demand for physiatrists will continue to exceed supply, on average, through the year 2000. Excess supply has emerged and will continue to emerge in selected geographic areas in the future. In order to maintain a level of demand, it was recommended that the field should emphasize the role of physiatrists in providing efficacious and cost-effective health care. An additional option would be to further broaden the scope of practice to include primary care services. An increasing trend of current graduates of PM&R residencies to enter musculoskeletal outpatient practices has also expanded this demand but not in the area of primary care. There is an ongoing effort to reassess the current and future PM&R workforce needs to help us to address our role in the provision of primary care services.

Unfortunately, there are several issues that will likely dampen the success of this effort. The above workforce projection is based on the premise that managed care will continue to grow at a moderate level. PM&R is not typically designated as a primary care provider in our current HMO and managed care systems. In addition, even if PM&R were designated as a primary care provider for persons with severe disability, it is unlikely that this would have a significant impact on the shortage of generalists. The total percentage of currently practicing physiatrists as compared with the total number of U.S. physicians is less than 1% (11). Based on our current training capacity, it is doubtful that there will ever be the number of physiatrists necessary to provide direct primary care for the large majority of persons with disability (11).

Some of the above assumptions are based on the premise that current practitioners and those in training in PM&R are willing to provide primary care services. A previous survey (51) of 106 PM&R physicians (55 physiatrists and 51 PM&R

residents) showed that only 39% agreed that PM&R should be designated as a primary care specialty. The majority also felt that these services should be restricted to those with severe disability (e.g., spinal cord and brain injuries). Overall, 53% felt that physiatrists are competent in providing general medical care, but only 38% were convinced that the current 4-year PM&R residency sufficiently prepares physiatrists to assume the role of a primary care provider.

residents) showed that only 39% agreed that PM&R should be designated as a primary care specialty. The majority also felt that these services should be restricted to those with severe disability (e.g., spinal cord and brain injuries). Overall, 53% felt that physiatrists are competent in providing general medical care, but only 38% were convinced that the current 4-year PM&R residency sufficiently prepares physiatrists to assume the role of a primary care provider.

Current PM&R training and residency curricula do not place a great focus on several areas that are essential to providing primary care services. These include health promotion and education, as well as preventive services (11). Significant changes would need to occur in our current residency requirements to provide the above training. This would likely require extension of our current 4-year training requirement, as well as substantial adjustments to our current residency experiences. A series of recommendations (56) for changes in the current PM&R residency curriculum were proposed to assist PM&R residency programs in providing for education in the provision of primary care. These include applying general preventive care principles and interventions to those with disabilities, expanding the role of “continuity clinics,” publishing a “study guide” on the topic of primary care for the disabled similar to the study guides currently published by the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and providing continuing education on common medical problems seen in the disabled and non-disabled population. Additional consideration was given to developing special or added qualifications in primary care for the disabled or expanding the availability of double board certification (current primary care-oriented combined programs involve internal medicine and pediatrics) to include family practice. Proposals such as these would require significant changes in our current training programs that may ultimately result in a negative impact on the continued growth and attractiveness of our field (11). Changes such as increasing the length of residency training and altering “quality of life issues” for residents and practicing physiatrists (the three “Ls” of primary care: low pay, long hours, low prestige) may be viewed as adverse by prospective PM&R residents (11). In fact, this may ultimately lead to further limitation of the accessibility of care to those persons with severe disabilities. Since the publication of the above recommendations, the issue of primary care within PM&R has become less prominent. A primary care special interest group remains within the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, but there has been little published within our PM&R literature on this topic. There have been no changes or additions in the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) PM&R residency requirements relating to the primary care issue, and no additional qualifications have been developed by the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (ABPM&R). In the late 1980s, however, the ABPM&R approved the concept of a 5 year combined PM&R and Internal Medicine residency. Though not truly accredited as a combined residency program by the ACGME, it is recognized as a viable option for being doubled boarded in the two specialties as long as both specialty boards (ABPM&R and Internal Medicine) preapprove the individual’s curriculum. Since its inception on July 1, 1990, only 77 physicians have completed the double boarding program, with only one resident currently in the training and scheduled to complete training in June 2009.

Other potential options to ensure provision of primary care services to those with severe disabilities include collaboration with other medical specialties as well as allied health providers. Several models have been developed that include close working relationships of physiatrists with internal medicine specialists, as well as physician extenders, such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants (30). The nature of this collaboration can be achieved in numerous ways; however, at a minimum, it should include physiatric education of the other primary care providers and team ventures with them to provide primary care for this population (11). A more detailed description of these types of collaborations is provided later in this chapter.

HEALTH PROMOTION IN PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES

The overall life course health profile of an individual with a disabling condition is the result of interaction among our disability management strategies, general health care practices, biologic and socioenvironmental factors, and lifestyle behaviors. Therefore, when physiatrists address the longitudinal health care needs of those with chronic disabilities, they must view disability-related health management and general health-promoting strategies as equally important components of care. In order to do this, they must enhance their frames of reference and incorporate the concepts of health promotion and secondary condition risk reduction.

Health Promotion and Related Models

Health promotion has several features that overlap with both primary care and medical rehabilitation. Most notable, all three emphasize education and encouragement of self-responsibility, and all address the potential or actual impact of a given physical or cognitive/emotional condition across several dimensions of health. Finally, all address both health maintenance and disease prevention so as to enhance and protect functional capacity over the life span.

As a general concept, health promotion describes all efforts directed toward helping individuals modify their lifestyles and behavior so as to promote a state of optimal health. Health promotion per se is not disease or health problem specific. However, the most important health-promoting behaviors recommended, as reflected by the Leading Health Indicators (LHI) in Healthy People 2010, the national health promotion agenda for the first decade of the new century, are: proper nutrition, weight control, smoking cessation, stress management, physical fitness, elimination

of any drug or alcohol misuse, disease and injury prevention, development of social support, and access to health care for regularly scheduled health surveillance to monitor health status (57).

of any drug or alcohol misuse, disease and injury prevention, development of social support, and access to health care for regularly scheduled health surveillance to monitor health status (57).

Early 20th century definitions of optimal health emphasized freedom from disease and issues related to hygiene. However, contemporary definitions of health typically reflect its complex multidimensional nature, incorporating biopsycho-social models related to the interaction of physical, emotional, and environmental spheres (58). Indeed, the Department of Health and Human Services defined optimal health as having a “full range of functional capacity at each life stage, allowing one the ability to enter into satisfying relationships with others, to work, and to play” (59). It posits that the pursuit of optimizing health in a given individual is impacted by the interplay between genetics, environment, lifestyle behaviors, personal health care availability, provider performance, and disease/condition management.

The merging of contemporary definitions of health, including the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (60), physiatry-oriented models of care, and the disabled individual’s own perceptions of well-being, can provide a conceptual framework upon which specific health-promoting and secondary condition risk reduction strategies can be formulated within the context of chronic disability. On many levels, the notion of health promotion for individuals with disabilities is a relatively new and emerging area in research and prevention programming. However, the impetus for closing the gap of disparity for this population of individuals is reflected in the agendas of Healthy People 2010, Healthy People 2020, and the relatively recent Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities (61). The guiding principle for this Call To Action is as follows: “Good health is necessary for persons with disabilities to secure the freedom to work, learn and engage in their families and communities.” There are four goals that will help accomplish this vision (61):

GOAL 1: People nationwide understand that persons with disabilities can lead long, healthy, productive lives.

GOAL 2: Health care providers have the knowledge and tools to screen, diagnose, and treat the whole person with a disability with dignity.

GOAL 3: Persons with disabilities can promote their own good health by developing and maintaining healthy lifestyles.

GOAL 4: Accessible health care and support services promote independence for persons with disabilities.

Health Protection and Secondary Risk Reduction

Intimately related to health promotion is health protection. Health-protecting behaviors, although overlapping to some degree with health-promoting behaviors, emphasize preventive measures that guard or defend an individual against specific injuries or illnesses. Public health interventions designed to protect health have traditionally been conceptualized as primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive measures. Primary prevention involves risk reduction and includes those activities undertaken to reduce the circumstances that would result in the subsequent development of a disease process or illness. Attention can be directed to the host (e.g., immunization, counseling on lifestyle behaviors), to the environment (e.g., elimination of physical hazards), or to a specific agent, if one is identified (e.g., contaminated water). Secondary prevention emphasizes the early detection and prompt intervention against asymptomatic disease processes in evolution. Screening efforts characterize this level of prevention. Tertiary prevention attempts to minimize disability from existing disease through medical treatment, education, and rehabilitation. Efforts to prevent the development of secondary conditions known to occur in those with specific disabilities incorporate principles from all three of these traditional models of prevention/health protection (62,63).

Expansion of these public health concepts for application among those with disabilities can provide the conceptual grounding for the development of disability-specific prevention protocols. Specifically, primary prevention for those with an existing disability should include appropriately tailored measures to eliminate risk factors for chronic conditions not necessarily directly related to their primary disability. Interventions may include protocols for health-promoting activities such as smoking cessation, weight control, reduction of substance abuse, increasing physical activity if feasible, and screening for age- and gender-specific carcinoma. Tailoring of these measures includes deliberate attention to the economic, logistic, architectural, and attitudinal obstacles to primary health care often encountered by persons with disabilities. The high prevalence rates of lifestyle risk factors amongst persons with disabilities warrants systematic attention to these areas (Table 60-1).

Secondary prevention measures in those with chronic disability should focus on ongoing anticipatory strategies to minimize the adverse health impact over time of the primary disability, superimposed aging issues, or new injuries. Emphasis is placed on early detection of secondary conditions that, if left unaddressed, can have deleterious effects on organ systems, performance of ADLs, and/or community reintegration over time (58,61). Tertiary prevention measures are then activated when appropriate.

TABLE 60.1 Prevalence of Risk Factors in Persons with Disabilities and Persons Without Disabilities | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

Tertiary prevention incorporates ongoing interval efforts to maximize and maintain functional capacity over the life course. Education in new skills and equipment is pursued as functional abilities change. Strategies to combat secondary deterioration in the performance of instrumental ADLs are pursued with attention directed to stabilizing or improving access to comprehensive specialized care and stabilizing access to personal care assistance/support services. Additional attention may be given to ongoing vocational rehabilitation and problem solving and the socioeconomic disincentives and obstacles often experienced by disabled individuals seeking a place in the workforce.

Health Literacy: Building a Knowledge Base

Health literacy is the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (58). It has been shown that thoughtful advice and counsel (i.e., patient education) about behaviors, lifestyle, and self-care practices that influence overall health can have far greater impact on health and longevity than specific screening tests or procedures (64,65). It is for this reason that emphasis on awareness and education is at the crux of health promotion activities. However, the success of health promotion educational efforts depends on a variety of issues that can be grouped into three categories: (a) issues related to health care professionals themselves, (b) issues related to the patient, and (c) issues related to clinical/environmental circumstances (66). Comments here are limited to the first category. Specifically, addressing the former, rehabilitation professionals may lack self-efficacy regarding their knowledge base and skills necessary for education and motivating individuals in health-promoting behaviors. Additionally, their own personal health enhancement beliefs and practices, their underestimating of patient interest or motivation, or their overestimating of patient knowledge will also influence the nature of clinical encounters and related patterns of education or referral (66,67). Continuing medical education activities, collaboration with primary care providers in the community, small group discussion, and case studies can be useful to physiatrists interested in building their knowledge base over time (68,69).

In order to facilitate effective patient education and behavioral change, the rehabilitation professional must have a clear understanding of available epidemiology assessment and intervention information related to commonly encountered disability-related and general health-related issues. Upon establishing this knowledge base, the physiatrist who so chooses can then routinely pose and answer the following questions during routine medical encounters:

What are potential disability-related or general health-related problems of which the patient should be aware?

What steps are necessary to clarify if the patient is at risk for specific conditions?

Is the problem present?

If present, what should be done?

Questions 1 and 2 require knowledge of (a) available epidemiologic data and risk factor information and (b) specialty-specific technical assessment skills. Question 3 requires skills in interpretation of the data secured, and Question 4 requires knowledge in appropriate education and therapeutic intervention options (57,70,71). Several factors other than knowledge predict the likelihood that individuals will adopt health-promoting and health-protecting behaviors. While providing knowledge and education are important parts of effective program design, other factors that affect the health decisions of patients should also be considered. Individual perceptions of risks, perceptions of self-efficacy in adopting recommended behaviors, physical and social environmental factors, and the perceived costs and benefits are four factors that inform personal health decisions. Incorporating the message design guidelines presented below can help more effectively promote behavior changes that result in enhanced health status (72).

To this end, investigators (72) have developed five specific guidelines regarding message design:

Messages should contain features that relate appropriate levels of risk.

Messages should contain features that bolster consumers’ beliefs that they are capable of adopting the recommended behaviors.

Messages should contain features that promote efficacy of recommendations.

Messages should contain features that encourage consumers to overcome environmental and social impediments.

Messages should contain features that promote the benefits and minimize costs.

While “marketable messages” are typically considered the purview of educational materials, the physiatrist can incorporate the specific principles into routine physician-patient encounters.

The Interdisciplinary Assessment of Health

A systematic health assessment is necessary to establish and document an individual’s current health status, lifestyle practices, and psychosocial variables that can influence health. Thereafter, goals can be established and pursued in a manner appropriate to the individual’s unique circumstances, resources, and personal desires (70

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree