Chapter 6 Preventive Health Care

Key Concepts in Evidence-Based Prevention

Evidence-Based Prevention

Definitions

Preventive services also involve costs of time and money to the patient and the health care system. Even services such as counseling that, on face value, appear to require minimal cost, actually involve a considerable cost in time and personnel resources, especially for counseling services that require intensive and repeated multifaceted counseling sessions to be effective. The time and personnel costs of counseling interventions must be balanced against the cost savings resulting from prevention or delay of a costly chronic illness. A well-established set of criteria from the World Health Organization (WHO) can help in evaluating whether screening is appropriate for specific diseases (Table 6-1).

Table 6-1 World Health Organization Criteria for a Screening Test

| 1. The condition being screened for should be an important health problem. |

| 2. The natural history of the condition should be well understood. |

| 3. There should be a detectable early stage. |

| 4. Treatment at an early stage should be of more benefit than at a later stage. |

| 5. A suitable test should be devised for the early stage. |

| 6. The test should be acceptable. |

| 7. Intervals for repeating the test should be determined. |

| 8. Adequate health service provision should be made for the extra clinical workload resulting from screening. |

| 9. The physical and psychological risks should be less than the benefits. |

| 10. The costs should be balanced against the benefits. |

From Wilson JMG, Jungner G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1968.

Preventive Services Task Force and Evidence-Based Prevention

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent panel of 16 private-sector experts in primary care, clinical prevention, and epidemiologic methodology (Guirguis-Blake, 2007). The USPSTF addresses a broad array of prevention topics important to primary care practice, including cancer prevention. Their recommendations address primary and secondary preventive services performed in primary care settings or recognized in primary care settings and referred to specialists. The 16 experts come from the clinical fields of family medicine, general internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, preventive medicine, behavioral medicine, and nursing. The USPSTF releases recommendations on a variety of topics relevant to family medicine that address preventive services for children, adolescents, and adults, including pregnant women.

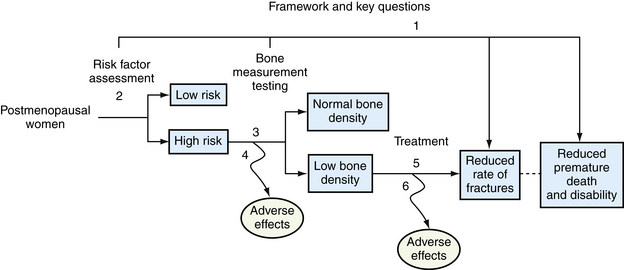

Using screening for osteoporosis as an example, the task force created a set of key questions beginning with an overarching question: Does osteoporosis screening result in decreased mortality or disability from osteoporosis? Because no evidence directly answered this question, a chain of intermediate key questions was systematically searched. What is the accuracy of screening tests (e.g., dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DEXA] scans)? What is the effectiveness of treatment of these screen-detected cases in preventing osteoporosis-related fractures, fracture-specific mortality, or overall mortality? What harms are caused by screening for and treatment of osteoporosis (Figure 6-1)? For USPSTF to recommend screening, each link in the chain of evidence must be supported by evidence, and there must be fair- or good-quality evidence that the benefits outweigh the harms. Any break in the chain of evidence (e.g., single key question for which there is insufficient evidence) results in a conclusion of insufficient evidence for that preventive service.

Challenges in Evidence-Based Prevention

Systems challenges, including a lack of linkages to community resources, delivery system support, and clinical information support (e.g., reminder systems, electronic health records), make it difficult to apply evidence-based prevention in practice. A systematic approach to offering preventive services enables a busy clinician to prioritize the most effective services. A systematic team approach ensures that immunizations are administered on time, screening tests are done appropriately, and counseling services are offered to those who need them.

Statistical Concepts in Prevention

Expressing the Burden of Disease

Risk Factors

A risk factor is a condition that is associated with an increased likelihood of a disease. For example, obesity is a risk factor for diabetes; obesity makes it more likely that a person will develop diabetes in his or her lifetime compared with someone who is not obese. Some risk factors are causal; the risk factor causes the disease. For example, smoking is a risk factor for and a proven cause of lung cancer; a smoker is many times more likely than a nonsmoker to develop lung cancer in his or her lifetime. Other risk factors are associations; people living at northern latitudes are more likely to have multiple sclerosis (i.e., there is no known causal relationship; it is simply an association). Risk factors for having a heart attack include gender, age, hypertension, smoking, and high cholesterol levels; other risk factors include sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and diabetes. Some risk factors are modifiable (i.e., can be changed), such as smoking, level of physical activity, and cholesterol levels, and others are nonmodifiable, such as age, gender, family history, and race. Some risk factors are behavioral risk factors, such as alcohol use, physical activity, and diet, and some type of change in behavior is required to modify these risk factors. Modifiable behavioral risk factors are significant contributors to most of the leading causes of death in the United States (Table 6-2). Preventive services strive to identify and change modifiable risk factors to prevent or delay disease.

Table 6-2 The 15 Leading Causes of Death—United States, 2006

| 1. Diseases of heart (heart disease) |

| 2. Malignant neoplasms (cancer) |

| 3. Cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) |

| 4. Chronic lower respiratory diseases |

| 5. Accidents (unintentional injuries) |

| 6. Diabetes mellitus (diabetes) |

| 7. Alzheimer’s disease |

| 8. Influenza and pneumonia |

| 9. Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis (kidney disease) |

| 10. Septicemia |

| 11. Intentional self-harm (suicide) |

| 12. Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis |

| 13. Essential hypertension and hypertensive renal disease (hypertension) |

| 14. Parkinson’s disease |

| 15. Assault (homicide) |

Modified from Heron MP, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, et al. Deaths: final data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, vol 57, no 14. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2009.

When considering prevention programs, it is often cost-effective to target populations who have a higher risk of disease rather than to offer the service to the general population, in whom the risk factor or disease may be uncommon overall. For example, some sexually transmitted infections are rare in the general population but are more prevalent among certain groups of people. In some areas of the United States, gonorrhea has a prevalence of zero, whereas other areas have concentrated populations with gonorrhea. If community clinicians were asked to design a program to prevent gonorrhea, they might selectively screen those with risk factors or those living in communities with a documented high prevalence of gonorrhea. A key concept to consider is that even with a high sensitivity and specificity, screening for a risk factor or disease that is rare will result in a low positive predictive value. In other words, the yield of screening will be low, and false positives may outnumber true positives. It is therefore important to consider the burden of a risk factor or disease in a given population before deciding whether screening for that condition is worthwhile.

Preventive Services by Disease Category

Cancer

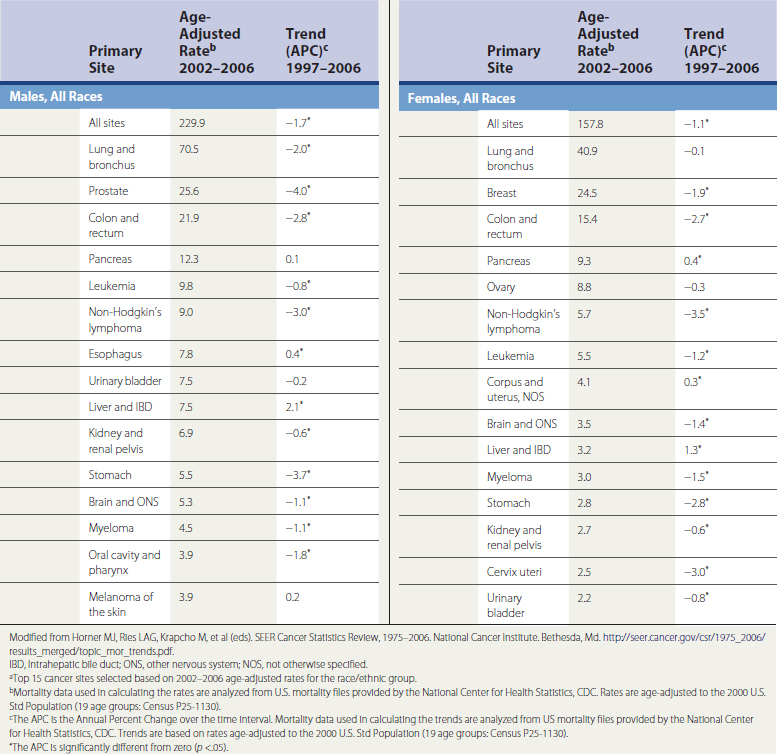

Almost one in every four deaths in the United States is caused by cancer, making it the second leading cause of death. It is estimated that approximately 1500 Americans die of cancer each day; a total of 562,340 cancer deaths were expected in 2009 (National Cancer Institute [SEER], 2009). The top causes of cancer-related deaths are presented in Table 6-3. Cancer has a significant impact on individuals, their families, and society as a whole. In 2001, there were an estimated 9.8 million people alive in United States who had received the diagnosis of cancer—some still had evidence of cancer, some were in remission, and the remainder were cancer free. In 2009, an estimated 1,479,350 new cases of cancer were diagnosed. In the United States the lifetime risk of a cancer diagnosis is one in two for men and one in three for women (ACS, 2009). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) estimate that the direct and indirect overall cost of cancer in 2008 was $228 billion when total health expenditures and loss of productivity from morbidity and premature death were included.

Colorectal Cancer

Effectiveness of Early Detection and Intervention

Screening for colorectal cancer reduces the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer by removing premalignant adenomatous polyps (USPSTF, 2008). Potential harms arise when false-positive screens lead to unnecessary invasive testing or false-negative results lead to false reassurance. Invasive screening procedures have risks such as bleeding and bowel perforation, which are even higher when therapeutic procedures (e.g., polypectomy) are performed (Pignone et al., 2002b).

Recommendation

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends screening average-risk adults beginning at age 50 with yearly FOBT or fecal immunochemical test annually, a flexible sigmoidoscope examination every 5 years, an FOBT plus flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, a double-contrast barium enema every 5 years, a CT colonography every 5 years, or a colonoscopy every 10 years.

Cervical Cancer

Breast Cancer

Burden of Disease

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in U.S. women; in 2008, an estimated 182,460 cases of invasive cancer and 67,770 cases of in situ breast cancer were diagnosed, with 40,480 breast cancer deaths (ACS, 2009). The risk for breast cancer increases with age: the 10-year risk for breast cancer is 1 in 69 for a woman at age 40 years, 1 in 42 at age 50, and 1 in 29 at age 60 (SEER, 2009). Several tools are available to predict risk of developing breast cancer for individual women (e.g., BRCAPRO, Gail, Claus, Tyrer-Cuzick). All these tools incorporate age and number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer into the calculations (Nelson et al., 2005). One example is found at www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/.

Effectiveness of Early Detection and Intervention

Trials evaluating the efficacy of mammography have limitations but have reported reductions in mortality of 15% to 32%, with a greater absolute risk reduction in older women. The number needed to invite for screening to extend one woman’s life is 1904 for women age 40 to 49 years and 1339 for women age 50 to 59 years. Controversy still surrounds routine screening of average-risk women between ages 40 and 49; cancer-related mortality reduction has been observed in this age group, although false-positive results are a concern. BSE has not been shown to reduce breast cancer mortality or significantly alter the stage at diagnosis. CBE has not been evaluated independent of mammography; screening with CBE and mammography is comparable to using mammography alone (Humphrey et al., 2002; USPSTF, 2009).

Recommendation

Lung Cancer

Ovarian Cancer

Recommendation

The USPSTF (2004) recommends against routine screening for ovarian cancer. Routine screening is not recommended by any organization. ACS states that women with a strong family history may consider screening, and ACOG recommends that clinicians remain alert for early signs and symptoms of the disease (Nelson et al., 2004b).

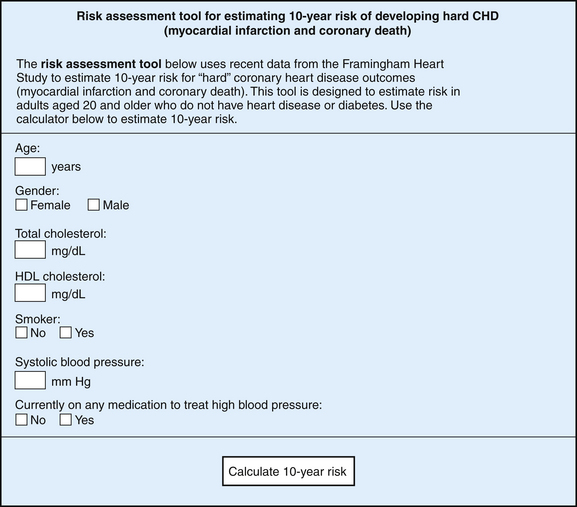

Heart and Vascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease is a major public health burden and the leading cause of death in the United States; it is the underlying or contributing cause in approximately 60% of deaths (Wolff et al., 2009). Effective screening tests and early preventive interventions are available for early asymptomatic states and modifiable risk factors (Figure 6-2). An assessment of cardiovascular risk using validated prediction tools is an important first step in preventing cardiovascular events. The most studied tools are based on Framingham data and are available online∗ and can be incorporated into electronic medical record systems.

Figure 6-2 Risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

(From the National Heat, Blood, and Lung Institute. http://hin.nhlbi.nih.gov/atpiii/calculator.asp?usertype=prof.)

Hypertension

Burden of Disease

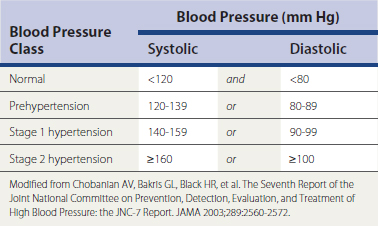

The risk of death from coronary artery disease and stroke (cerebrovascular accident, CVA) is doubled with every 20–mm Hg systolic or 10–mm Hg diastolic increase in BP (Table 6-4). Elevated BP is also associated with heart failure and renal disease (JNC-7, 2004). Treatment and control of hypertension are less than ideal; 68% of hypertensive adults are treated with BP medications, and of those treated, 64% had their BP lowered to recommended levels (Ostchega et al., 2008).

Hyperlipidemia

Burden of Disease

Of U.S. adults, 16% have a total cholesterol level greater than 240 mg/dL. Women have a higher prevalence of elevated total cholesterol than men (Schober et al., 2007). Low HDL is much more common in men than women (AHA, 2005). Total cholesterol levels higher than 200 mg/dL account for 27% of coronary heart disease (CHD) events in men and 34% in women. Elevated total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) increase the risk of CHD linearly (Pignone et al., 2001).

Recommendation

The USPSTF recommends screening all men older than 35 and men younger than 35 if they are at increased risk for CHD. Women older than 20 should be screened if they are at increased risk for CHD. The overall benefit of screening for lipid abnormalities for women not at increased risk and for younger men not at increased risk is small (USPSTF, 2008). AAFP agrees with the USPSTF recommendation. The third report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s National Cholesterol Education Program’s Expert Panel on the Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) recommended screening adults older than age 20 every 5 years (ATP III, 2002).

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Coronary Heart Disease and Cerebrovascular Disease

Effectiveness of Early Detection and Intervention

Hormone replacement therapy does not prevent CHD in postmenopausal women (Anderson et al., 2004; Rossouw et al., 2002), and evidence does not support a benefit from vitamin supplements (Lee et al., 2005). There is good evidence that screening for CAS with an ultrasound leads to important harms, including strokes from confirmatory tests or surgery. For men at increased risk for CHD, aspirin prophylaxis decreases the rate of CHD events; and for women at increased risk of strokes, aspirin decreases the rate of strokes (Berger et al., 2006; USPSTF, 2009). The ideal dose is uncertain, but low doses (75 mg) are as effective as high doses (325 mg). Smoking cessation, BP and lipid control, a healthy diet, and exercise have also been shown to be beneficial in preventing cerebrovascular disease events.

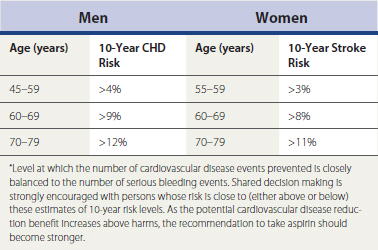

Recommendation

The USPSTF recommends against using ECG, exercise testing, or CT scanning to screen low-risk adults for CHD. Evidence is insufficient to recommend these techniques even for adults at increased risk (USPSTF, 2004). AAFP does not recommend routine ECG in asymptomatic children or adults as part of a periodic health examination (Pignone et al., 2003). USPSTF concluded that the evidence is insufficient for the use of nontraditional risk factors to screen asymptomatic men and women. They recommend against screening for asymptomatic CAS in the general adult population. USPSTF recommends the use of aspirin for men age 45 to 79 years and women age 55 to 79 when the potential benefit from a reduction in MIs or strokes, respectively, outweighs the potential harm from an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage (Table 6-5). It is important to discuss both the benefits and the harms with patients. Aspirin in younger men and women is not recommended because they are likely to experience more harm than benefit. There is no evidence to use aspirin for cardiovascular disease prevention in average-risk men and women 80 years or older (USPSTF, 2009).