FIGURE 40-1. Lateral radiograph with tibial reconstruction with reconstruction with proximal tibial augments, posterior femoral augments, and uncemented stem fixation.

Anterior-Posterior View The anterior-posterior (AP) radiograph provides valuable information about component fixation, position, and sizing as well as the presence of bone loss. Tibial radiolu-cencies are best identified on the AP view. Radiolucencies may be indicative of aseptic or septic loosening depending on their location and extent. The presence of radiolucencies at all component interfaces is suggestive of infection and should be assessed prior to revision arthroplasty. The position of the intramedullary canals relative to condyles can be determined on both the AP and lateral films, which is helpful during intramedullary reaming during the revision to prevent cortical perforation and subsequent component malposition. Over or under sizing of the components is determined. Overhang of the tibia may correlate with the presence of pain over the medial aspect of the knee. The joint line may be assessed as measured from the adductor tubercle or the fibular head on the AP view. Standing films may indicate areas of polyethylene wear or more subtle instability not seen on non–weightbearing views (Fig. 40-2).

FIGURE 40-2. Standing AP radiograph of a mobile bearing TKA with recurvatum and subluxation and clinical instability.

Lateral View The lateral radiograph also shows the exit of the diaphyseal canals at the level of the joint line that is important when intramedullary instrumentation is utilized for bone preparation and intramedullary stems are utilized for implant fixation. The lateral film also reveals posterior femoral bone loss, tibial tubercle continuity, integrity of the femoral and patellar fixation interfaces, the amount of posterior tibial slope present, anterior notching of the femur, and oversizing of the femoral component. The position of the femoral component in the AP plane may account for various forms of instability. An example of this is if anterior referencing instrumentation was utilized, the posterior condyles may be overresected and be a contributing factor to flexion instability.

Patellar baja or alta is best recognized on the lateral radiograph and may effect surgical exposure during the revision TKA in the case of patellar baja due to infrapatellar scar from prior surgery. The In-sall-Salvati ratio11 may be measured on the lateral film and compared to preoperative films and any prior postoperative films. The distance from the tibial tubercle to the patella may be an indication of extensor mechanism continuity.

Standing Long Leg View Standing views from the hip to the ankle are utilized to assess the anatomic and mechanical axes, extra-articular deformities, coronal plane alignment, femoral neck-shaft angle, and for templating purposes (Fig. 40-3). The presence of other arthroplasties such as an ipsilateral hip replacement must be visualized prior to knee reconstruction especially if intramedullary stems or guides are to be used during the revision reconstruction. The need for offset stems can be estimated based on the long leg AP and lateral radiographs.

The long leg view also allows for measurement of femoral neck-shaft angle which is important in determination of the angle of the upcoming distal femoral resection. Cases with substantial coxa vara or valga may necessitate angular resection adjustments. Joint line obliquity is also best determined on long leg films. These images often reveal under or over correction of prior deformity, which are important factors to consider in the formulation of the mechanism of failure of the knee arthroplasty. The reconstructive plan should recognize these deforming forces and aim to correct them. As the intramedullary canals are easily visible on longer films, the exit of the diaphyseal canal at the level of the joint line can be assessed at this time in order to plan for intramedullary canal access for instrumentation and stem fixation.

FIGURE 40-3. AP radiograph close up view of the knee with the mechanical axis marked on a long leg radiograph showing the mechanical axis passing medial to the knee due to femoral component varus alignment resulting in tibial component loosening despite prior tibial revision.

Prior diaphyseal deformity can be quantified on the long films. Adjustment of the distal femoral valgus osteotomy and the proximal tibial resection can be made in order to correct the overall alignment in light of any additional diaphyseal deformity that is present. Significant deformity may require osteotomy in order to realign the mechanical axis of the limb (Fig. 40-4).

FIGURE 40-4. Preoperative valgus deformity due to supraconylar femur fracture combined with femoral component loosening.

Merchant Patellar View Patellar position can be assessed on the lateral and then on a tangential patellar view such as a Merchant view.8,9 This view can be modified by capturing the knee in varying degrees of flexion to provide some information on patellar tracking. Patellar bony deficiencies and subluxation are assessed with the combination of the Merchant and lateral radiographs. Patellar tracking and tilt may be indicative of soft tissue imbalance or component rotational malposition, particularly internal rotation of the femoral and/or tibial components relative to their native axes. The coronal plane malposition of the patellar component may result in anterior knee pain due to osseous patellar contact from peripheral bone not covered by the patellar component. In cases of severe deficiencies, planning may necessitate removal of the prosthesis, osteotomy with or without bone grafting,12 or specialized patellar component insertion.13

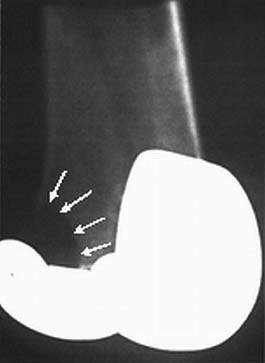

Special Radiographs Fluoroscopic films may identify the presence of bone-cement interface radiolucencies not seen on routine films due to inadequate visualization of the bone-cement interface secondary to placement of the x-ray beam out of plane with the implant interface. In a series of 20 TKA subjects with plain radiographs judged to be normal, aseptic loosening was observed in 14 of 20 cases (70%) when fluoroscopically guided radiographs were obtained.14 Oblique films may clarify the presence of osteolytic defects, especially in the posterior femoral condyles and tibia (Fig. 40-5). Computed tomography may further delineate osteolytic areas poorly visualized on plain films as well as assist in detection of component rotational malalignment. CT scans provide increased accuracy over plain radiographs in identification of femoral rotation errors about the epicondylar axis and tibial component rotation with respect to the tibial tubercle and extensor mechanism. Patellar subluxation may result from internal rotation of either the femoral or tibial components and may be a multifactorial finding unrelated to the patellar component itself.

FIGURE 40-5. Oblique radiograph demonstrating an osteolytic defect in lateral femoral condyle of a posterior cruciate substituting TKR.

Nuclear bone scans can facilitate identification of biological loosening or sepsis. Indiumlabeled WBC scans are utilized to detect infection. Rand et al. reported on 38 patients with a painful TKA who had surgical exploration after 111In leukocyte scanning. The scan had an accuracy of 84%, a sensitivity of 83%, and a specificity of 85% in detection of infection.15 Component loosening prior to migration and stress fractures in the tibia or fibula due to excessive loading may also be seen on nuclear scans. While reflex sympathetic dystrophy is best evaluated by clinical exam and sympathetic blocks, the diagnosis may be further evaluated with bone scans.16–18

Templating begins with clarification of radiograph magnification. This can be determined with radiographic markers or through computerized measurements on digital films. The primary goals of templating are to determine the new implant size and position and to assess if specialized components such as offset stems or trays or specialized procedures such as osteotomies are required. Templating also determines which methods will be required to create an osseous environment for stable implant fixation, a neutral mechanical axis, equal and balanced flexion and extension gaps, and a functional and centralized extensor mechanism.

Component position may guide intraoperative correction of existing malalignment such as tibial component varus that would require lateral tibial bony resection or medial tibial augmentation. Component size is measured on both the anteroposterior and lateral films, compared to existing implants and a plan made for the revision components.

Component Sizing The sizing of the components should be aimed at restoring appropriate ligament balance and function of knee. Both over-sizing and under-sizing of the implants may result in an unsatisfactory result. Undersizing may result in excessive laxity and flexion instability, while oversizing may result in pain and loss of motion.

Bone is routinely missing in the revision TKA. Typically at least 1 cm of bone was removed from both the femur and tibia at the time of initial TKA. Additional bone loss may be encountered due to the mechanism of failure (component loosening, osteolysis, etc.) and removal of prior components during the revision procedure. The need for augments to restore component size, which in turn restores ligamentous balance, should be recognized. The films of the failed arthroplasty can be compared to contralateral knee (if nonimplanted) or initial prearthroplasty films to help determine the need for bone graft or prosthetic augmentation at the time of reconstruction to achieve ligament balance in flexion and extension and restoration of the joint line. Templating may also guide intraoperative tibial resection in order to determine the amount of tibial bone to be resected or rebuilt in order to correct existing deformity in the proximal tibia or distal femur resulting in varus or valgus limb alignment.

Landmarks that can be reproducibly assessed during the revision surgery should be utilized to determine joint line position. Measurements can be made from the adductor tubercle, medial and lateral epicondyles, and fibular head, and compared to preoperative films or images of the contralateral knee, for subsequent metaphyseal referencing. The inferior pole of the patella is usually within 1 cm of the joint line, although this varies on the degree of knee flexion. The medial epicondyle and lateral epicondyles are approximately 30 and 25 mm from the joint line, respectively. Soft tissue balance will be the final factor that determines proximal-distal position of the components in extension, the AP position in flexion, and the size of the femoral component in the sagittal plane.19 These two gaps may be adjusted with prosthetic augmentation, additional bone resection or grafting, or component size.20

Component Position

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree