7 PREHOSPITAL CARE OF THE TRAUMA PATIENT

Although prehospital care is not typically a nursing activity, two critical points make it an important component of this text and trauma nurse training programs. First, trauma nurses are often members of critical care transport teams both on traditional ground ambulance crews and on aero medical services. These critical care transport teams are most often involved in transferring patients from one facility to another but they can also be involved in direct field response. Second, it’s important for trauma nurses to have knowledge of what care is performed during the prehospital phase of the trauma cycle. It is essential to ensure optimal communication between prehospital personnel and the in-hospital trauma team so that appropriate preparations can be made in advance of the patient’s arrival. This chapter defines prehospital care, describes its components, and explains the connection between the prehospital and intrahospital operations in trauma care.

THE PREHOSPITAL CARE TEAM

Trauma directly affects approximately 60 million people per year in the United States. In 2003, 164,002 died of those injuries.1 The significance of this problem has led to the development of specialized systems to respond to the injured, with the goal of decreasing mortality and morbidity. Teamwork is an essential determinant in the outcome of trauma care, for there are few individual successes and even fewer individual failures.2 Each member of the team is dependent on the others.

ACCESS TO EMERGENCY MEDICAL SYSTEMS

The three-digit number 911 was set aside by Congress in the late 1960s to provide a simple method for accessing assistance from public safety personnel. Currently 911 systems exist in approximately two thirds of the United States. Calls to 911 are received by emergency dispatchers, who are trained in emergency medical dispatch or priority medical dispatch.3 Many of these “trained” dispatchers have also completed emergency medical dispatch programs based on curriculum provided by the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). Dispatchers are a critical component of the prehospital care team. A 911 communications center receives requests for help, determines the type of resources to deploy, and documents all activity related to a particular incident. The simplest 911 systems route calls to the appropriate central dispatch center. Enhanced 911 centers are able to display the address of the caller on monitors to speed the dispatch of assistance to the callers. By federal mandate, even cellular calls can provide location. Minimally, 911 calls will go to the 911 center servicing the area where the phone is located. The latest enhancements to this system can pinpoint the location of the caller to within a few feet. Internet-based phones initially presented a problem in that the location of the phone could not be determined at 911 centers. Here again, federal regulation has mandated that these phones report their location into the system as well. Some of the providers have come online, but Internet-based phone users should check with their 911 centers and service providers to determine whether the phone location can be retrieved.

Determining the most desirable use of prehospital resources—police, fire, paramedic unit, or air medical helicopter—is a complex process. Each prehospital system has protocols fine-tuned to the available resources for the area that guide the dispatcher’s decision making. The dispatcher will solicit key initial information such as the type and location of the incident and the number of individuals involved.4 This information will direct the dispatcher to activate the appropriate team members to facilitate the delivery of care and restore order to potentially life-changing situations. The dispatcher will also give prearrival instructions to the caller.

The types of available prehospital care resources vary from region to region. Contrary to public perception, in many parts of the United States prehospital care is provided by volunteer personnel. Some emergency medical systems (EMS) programs are fire based, whereas others are private or third-party service agencies. Currently in the United States there are about 891,000 EMS professionals transporting 16.2 million patients annually.5 Department of Labor statistics for 2004 showed that 4 of 10 emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics work for private ambulance services, 3 of 10 work for local government agencies, and 2 of 10 are employed by hospital-based services.6 Currently there are four levels of trained prehospital care providers in the United States: emergency medical responder (formally known as first responders), EMT, advanced emergency medical technician (AEMT) (formally known as EMT-Intermediate), and paramedic. Table 7-1 describes the training required and level of care that can be provided by each level prehospital provider.7

TABLE 7-1 Prehospital Care Providers: Required Training and Primary Role

| Team Member | Training and Primary Role in Trauma Scene Response |

|---|---|

| Medical first responder | Trained first responders act as a bridge until transport-trained EMTs and/or paramedics arrive on the scene. Typically require 40 hours of training. Medical first responders may or may not be certified or licensed in the state in which they work. |

| Emergency medical technician (EMT) | Basic level of emergency responder trained to complete basic assessments, initiate oxygen therapy, and provide advanced first aid. 110 hours or more of training. Certified or licensed. |

| Advanced emergency medical technician (AEMT) | EMTs trained in additional ALS skills, such as insertion of IVs, intubation, or administration of a limited amount of specific medications. Up to 400 hours of training. Licensed or certified. |

| Paramedic | Advanced-level emergency responder trained to complete advanced assessments, initiate IV therapy, administer drugs, and institute airway management, including endotracheal intubation; practices as a physician extender; all practice directed by standing orders and protocols or by online physician order. More than 1,000 hours of training. Licensed or certified. |

| Emergency communications radio nurse (ECRN) | Specially trained RN who provides online consultation to prehospital personnel; participates in destination choices. Licensed provider. |

| Flight nurse | Specially trained RN with broad experience in emergency and critical care nursing. Routinely an expanded practice role. Provides patient care in a helicopter or fixed-wing aircraft. Performs advanced assessments and interventions including but not limited to endotracheal intubation, RSI intubation, central line placement, chest tube placement, and pharmacologic intervention. Practice directed by a physician medical director and authorized program-based protocols. Licensed provider. |

| Flight paramedic | Specially trained paramedic with broad experience in prehospital care and transport. Most flight nurses and flight paramedics receive the same flight-specific training. Many perform similar skills, including advanced assessments and intervention such as endotracheal intubation, RSI intubation, central line placement, and chest tube placement. Practice directed by a physician medical director and authorized program-based protocols. In some areas practice may be limited by state-defined paramedic scope of practice. Licensed in some states, certified in others. |

| Flight physician | Physician serving as an air medical team member. Level of experience varies from intern to well-seasoned, board-certified physician specialist. Licensed provider. |

| Medical director | Multifaceted role, varies system to system. Provides medical direction in policy and procedure formation and on-line advice to responding teams. Most agencies involved in prehospital response have assigned physicians for this role. Ensures quality care delivery. |

ALS, Advanced life support; RSI, rapid sequence intubation.

INCIDENT COMMAND

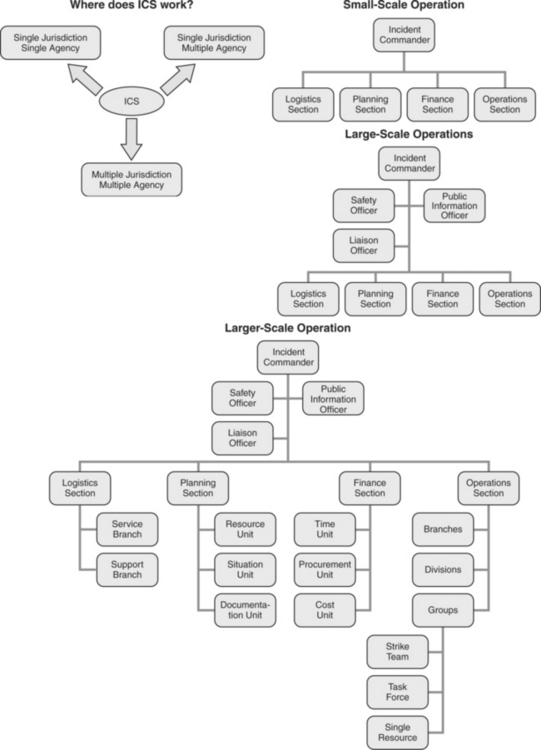

In the early 1970s the incident command system (ICS) was adopted by fire and police services in the United States.8 The purpose of the ICS was to formalize job descriptions of prehospital care providers and ensure effective, clear, concise communications between providers in mass casualty situations. The intention was to create a mechanism that brings order to chaos.

The ICS is a field management tool that is flexible enough to be exercised in a variety of incidents (e.g., a building fire or a roadside crash). It is organized around five major activities: command, operations, planning/intelligence, logistics, and finance/administration (Table 7-2). This system requires the designation of an incident commander (IC) who is responsible for all functions required at the response. The IC may choose to delegate authority to others during the incident; however, this does not relieve the IC from overall responsibility. The ICS incorporates the principle of unified command, which allows all agencies that have jurisdictional or functional responsibility (e.g., state-based highway patrol and a local fire agency responding to a multiple-vehicle crash on a state road) to jointly develop a common set of incident objectives and strategies. Unified command ensures that no single agency loses authority or accountability9 (Figure 7-1).

TABLE 7-2 Incident Command System: Function Overview

| Functions | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Command | Coordinates all activity; a command is present for all incidents |

| Operations | Directs activity (resources, machinery, personnel) required to meet incident goals |

| Planning/intelligence | Collects, evaluates, and displays incident information; maintains status of resources; prepares incident action plan and incident-related information |

| Logistics | Provides adequate services and support to meet needs of incident resources |

| Finance/administration | Tracks incident-related costs, including personnel and equipment |

Modified from State of California, Office of Emergency Services: Standardized emergency management system field course module 2—principles and features of ICS, Sacramento, 1995, Office of Emergency Services.

FIGURE 7-1 Where does ICS work?

(From Prehospital Trauma Life Support Committee of the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians in Cooperation with the Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons: Prehospital trauma life support, 6th Edition, p 84, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby Elsevier.)

THE NATIONAL INCIDENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

On February 28, 2003, President Bush issued a Homeland Security directive instructing the Secretary of Homeland Security to develop and administer a National Incident Management System (NIMS). The NIMS is a comprehensive, national approach to incident management designed to be applicable across a full spectrum of events regardless of size, complexity, or cause. This national system identifies common terminology, architecture, planning, interface, and training, ensuring that all participants in an incident know their roles and how their roles fit into the overall plan. The common terminology and language ensures that communications and resourcing are best supported. The NIMS was authorized on March 1, 2004, and all emergency management agencies were mandated to adopt the system. Further, enforcement of compliance was ensured by tying all federal emergency response grants to NIMS compliance. Any emergency responder should receive training in NIMS and any agency receiving federal grants will have to show NIMS compliance. NIMS activities are coordinated through the NIMS Integration Center available on the Federal Emergency Management Administration website.10

COMMUNICATIONS

Communication is the cornerstone to an effectively run prehospital response and it is essential for a successful EMS system.11 Effective communication systems are all encompassing; they include information sharing with the public, EMS units, fire, police, air operations, and medical directors. The tools used for effective communication include mobile data terminals (MDT), two-way radios, cellular/digital/satellite phones, and pagers.

Radios are a mainstay of EMS communications. In this era of high technology, every agency and municipality involved in EMS response has internal and external radio communication capabilities. Like telephone numbers, radio frequencies are dedicated to certain agencies by the Federal Communications Commission and, unlike traditional phone lines, can be designated for specific activities. For example, a certain frequency may be designated as a tactical frequency, and all responders from agencies participating in an extrication will be directed to that frequency, but medical operations may use another frequency. Radio channels are divided into bands and frequencies. Table 7-3 outlines the available radio frequencies and the pros and cons associated with their use.

TABLE 7-3 Pros and Cons of Tools Used for Communication

| Communication Tool | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Radio Channel Frequencies and Bands | ||

| Very high frequency (VHF) | Long range | Often disrupted |

| VHF—low band | ||

| VHF—high band | ||

| Ultra high frequency (UHF) | ||

| 800 megahertz band | ||

| Cellular/digital/satellite phones | ||

| Mobile data terminals (MDT) | ||

| Pagers | One-way or two-way transmission of information |

THE TRAUMA SCENE

SAFETY AT THE SCENE

It is critical to eliminate the potential for additional injuries. The scene must be evaluated for fire sources, potential explosions, continued gunfire, “hot” electrical wires, unruly crowds, and other hazards. First responders alter traffic patterns to limit risk of further incident and call for additional resources as indicated. If the incident involves a vehicle, it must be determined whether the vehicle is secure. Is the vehicle at risk of rolling down an embankment? If the vehicle struck a tree, is that tree strong enough to serve as a brace? If the vehicle is not secure, it must be secured with cribbing (wood blocks or air bags) to ensure stability.

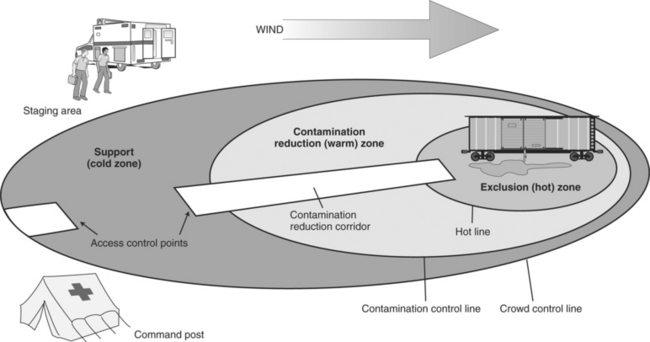

Hazardous materials (HAZMAT) (substances capable of posing unreasonable risk to health, safety, or property) present a significant threat to prehospital operations. The presence of HAZMAT can elevate an incident that affects one individual to a catastrophic event affecting an entire metropolitan area. It is the responsibility of the emergency response team to suspect HAZMAT when responding to incidents involving trucks, railcars, industrial buildings, or unmarked containers and to take appropriate precautions (Figure 7-2).

FIGURE 7-2 The scene of a WMD or HAZMAT incident is generally divided into hot, warm, and cold zones.

(From Chapleau W: Emergency first responder, p 351, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

The approach to a HAZMAT scene is one of caution and investigation. Fire and other public safety personnel should enter the scene in a coordinated fashion. Responding teams should ascertain the name and chemical number of the material if possible. This information may be collected from the truck’s “bill of lading” and material safety data sheet or perhaps other documents accompanying the driver. If this information is available, the prehospital care provider may obtain more information about the material from the USDOT or the Chemical Transportation Emergency Center (CHEMTREC).12 CHEMTREC, a public service of the Chemical Manufacturers Association, supports a 24-hour telephone number (800-262-8200) allowing access to databases that assist in identifying hazardous zones and decontamination priorities. Another source for HAZMAT advice is the regional poison control center.

“Hazardous material” is not a misnomer. Such a substance can add more hazard and risk to the rescue, extrication, and transport of an injured individual. If the victim has had contact with a hazardous substance, a specific course of action is advocated (Table 7-4) to minimize the physiologic effects and to protect medical personnel in the prehospital and in-hospital phases of care. The objectives of scene safety are to keep the patient and crew safe and to complete the job at hand. Once the scene has been secured, patient care may begin.

TABLE 7-4 Interaction With Hazardous Materials

Awareness training is the initial HAZMAT training level and all prehospital care providers should have this level of training. This level of training provides the knowledge necessary to prevent prehospital care providers from getting into scenes with HAZMAT and creating further exposures and injuries. The next level of training is the operations level, which is completed by providers who isolate the hazard. HAZMAT technicians are trained to the level of being able to attempt to stop or neutralize the release of the hazard. Finally, the highest level of HAZMAT training is the specialist level, in which training focuses on providing the skills for command and control of HAZMAT operations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree