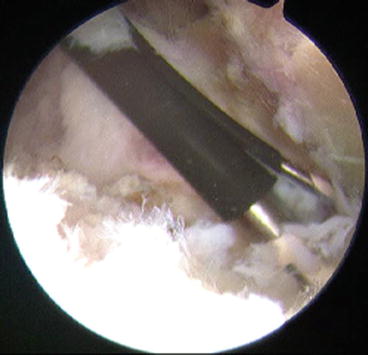

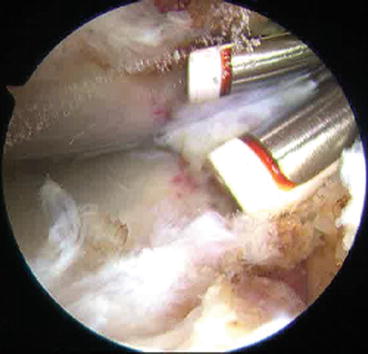

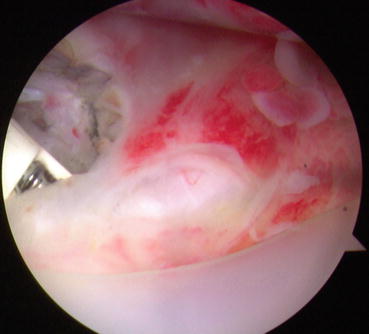

Fig. 7.1

Initial arthroscopic evaluation may be confusing due to reflection of the soft tissue by the humeral head

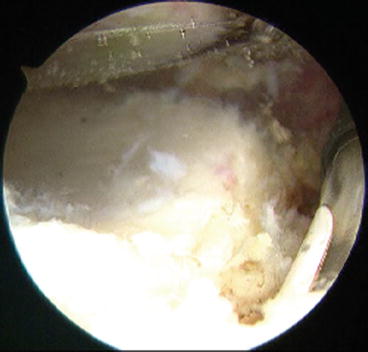

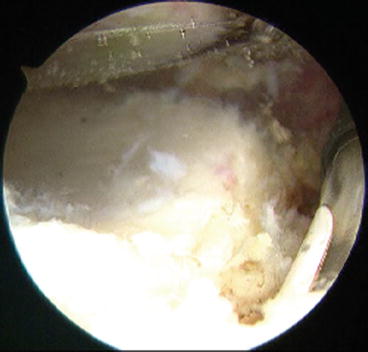

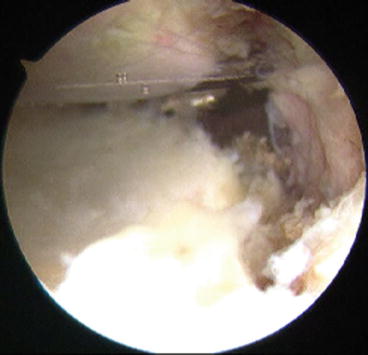

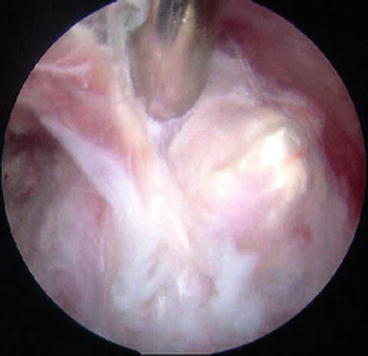

Fig. 7.2

A side effect type cautery device can be inserted and the interval released to the coracoid base

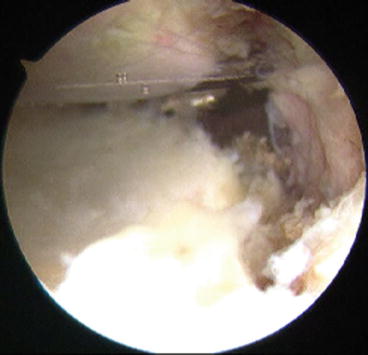

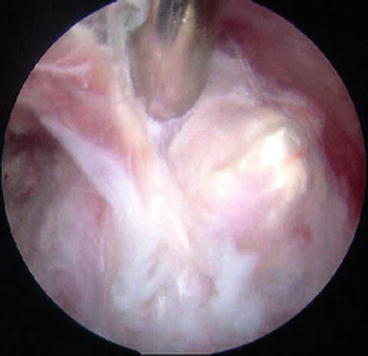

Fig. 7.3

The cautery is used just outside the normal (for humeral head replacement – HHR) or prosthetic (for TSA) glenoid to excise the anterior capsule and labrum down to the 4 o’clock position

The superior capsule beneath the supraspinatus is similarly released, but the dissection is limited to stay within 1 cm of the joint to avoid the suprascapular nerve (Fig. 7.4).

Fig. 7.4

The superior capsule beneath the supraspinatus is similarly released, but the dissection is limited to stay within 1 cm of the joint to avoid the suprascapular nerve. The humeral prosthesis is at top, the prosthetic glenoid at bottom, and the cautery to the right going over the superior glenoid neck

The viewing portal is then transferred to the anterior portal and the cautery placed in the posterior portal. The release is continued beneath the infraspinatus superiorly without attempting to find the scapular spine. The posterior capsule is released with the cautery staying right on the bone of the glenoid down to the 7 o’clock position posteriorly (Fig. 7.5).

Fig. 7.5

The posterior capsule is released with the cautery staying right on the bone of the glenoid neck down to the 7 o’clock position posteriorly

A posterior, inferior portal is then created. The arthroscope may be left anteriorly or placed in the standard posterior portal. The inferior capsule and labrum are carefully dissected off the glenoid, again using the cautery (Fig. 7.6). In this 5–7 o’clock position, the axillary nerve may be quite close, or even scarred to the capsule, so caution is essential. If there is any question, a small posterior incision with dissection down to the quadrangular space will allow direct inspection of the axillary nerve and retraction of it away from the capsule.

Fig. 7.6

A posterior, inferior portal is then created. The arthroscope may be left anteriorly or placed in the standard posterior portal. The inferior capsule and labrum are carefully dissected off the glenoid, again using the cautery. It is important to recognize the proximity of the axillary nerve during this part of the procedure

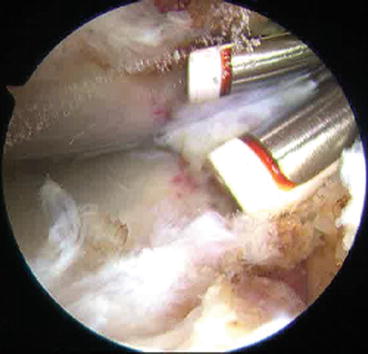

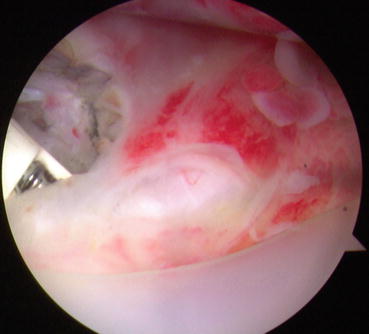

Once the capsule has been completely and circumferentially released from the glenoid, the rest of the rotator interval tissue may be excised. At this point, an evaluation of the glenoid for possible loosening can be performed (Fig. 7.7). There should be no motion between the prosthesis and the bone of the glenoid. The arm is then removed from the holding device and motion rechecked.

Fig. 7.7

Once the capsule has been completely and circumferentially released from the glenoid, the rest of the rotator interval tissue may be excised. At this point, an evaluation of the glenoid for possible loosening can be performed. The glenoid is the white plastic on the inferior aspect of the figure

The arthroscope is inserted into the subacromial bursa. A lateral portal is established and initial dissection is in the subdeltoid bursa in order to avoid injury to the rotator cuff (Fig. 7.8). There are usually considerable adhesions in this area. Excision of all of these adhesions is essential, so one must debride distally while staying close to the humerus and always keeping the shaver facing away from the deltoid muscle to avoid injury to the axillary nerve. In some cases, a blunt dissector placed via the anterior portal may be used to hold the muscle and nerve up and away from the shaver.

Fig. 7.8

The arthroscope is inserted into the subacromial bursa. A lateral portal is established and initial dissection is in the subdeltoid bursa in order to avoid injury to the rotator cuff

Once the subdeltoid debridement has been completed, the dissection can be continued proximally to find the acromion. The cautery device is used on the undersurface of the acromion so that the rotator cuff tissue can be preserved. The arthroscope is transferred to the lateral portal and using anterior and posterior instrument portals, all soft tissue is dissected free from the acromion, the coracoacromial (CA) ligament, the coracoid and subcoracoid bursa and the conjoined tendon, the acromioclavicular (AC) joint, and the scapular spine. Posteriorly, adhesions between the deltoid and the rotator cuff should be excised.

Motion is carefully reassessed and should be normal. In some cases, a further dissection of the soft tissue around the subscapularis and rotator interval may be necessary to achieve full motion. We usually document the motion with the arthroscope to give to the patient (Fig. 7.9a–c). Fluoroscopy may be used in the operating room (OR) or radiographs may be obtained either in the OR or recovery rooms to ensure no fractures or instability have occurred.

Fig. 7.9

(a) Full abduction is achieved with no stress on the right shoulder post arthroscopic release. (b) Full external rotation is achieved in 90˚ abduction with no stress on the shoulder post arthroscopic release. (c) Full internal rotation is achieved in 90˚ abduction with no stress on the shoulder post arthroscopic release

7.1.5.4 Open Release

The patient is placed in the same position as for TSA. The previous deltopectoral approach is utilized. The coracoid is identified and the subscapular muscle evaluated. Subcoracoid, subdeltoid, and subacromial adhesions are removed. The axillary nerve is identified and carefully protected, and if necessary dissected from the inferior capsule. The rotator interval is completely released and excised.

7.1.5.5 Postoperative Course

Radiographs should be taken in the recovery room to make sure no inadvertent fractures or dislocation have occurred. The patient is usually admitted overnight for continuous passive motion (CPM) and therapy. Outpatient PT for maintenance of motion gained in surgery is continued for at least 4 weeks.

7.1.6 Results

There is little information on results of post arthroplasty release. However, in writing this chapter, the senior author had the opportunity to review 12 surgical patients referred for noninfected post arthroplasty stiffness; 6 patients had sustained a proximal humerus fracture treated with humeral head replacement, 2 patients had simultaneous surface replacement and rotator cuff repair, and 4 patients were stiff total shoulder arthroplasty patients. All 12 patients had failed extensive nonoperative management including injections and therapy; 4 patients also failed manipulation under anesthesia. The average preoperative visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain was 8 (range 5–10) and the average preoperative motion was flexion of 100˚, abduction of 80˚, external rotation of 0˚, and internal rotation of 0˚. All 12 patients underwent arthroscopic release by the described technique; 5 patients regained completely normal range of motion, 4 patients 90 % of normal, one patient 75 %, and in 2 patients (one HHR for fracture, 1 SRA with RCR) motion gains were relatively modest. The VAS pain scale decreased to an average of 3 (range 0–10) with one patient remaining at 10. Eleven of the 12 felt surgery was beneficial.

7.1.7 Conclusions

Stiffness post total shoulder arthroplasty is a rarely reported complication with an unknown incidence. Open or arthroscopic release may be indicated to improve the restricted motion and will allow assessment of the prosthetic stability and help rule out infection by providing deep culture and tissue biopsy. Limited evidence exists to evaluate the success of this treatment.

7.2 The Stiff Shoulder Post SLAP Repair

7.2.1 Introduction

The superior labrum has been an area of interest since the advent of arthroscopy. The initial report of superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears by Snyder et al. [20] in 1990 that followed on the report by Andrews et al. [1] in 1985 on tears at the base of the biceps has focused quite a lot of interest in the subsequent years on this area of the shoulder. Both Andrews and Snyder documented a very low incidence of significant tears, and both managed their series with debridement only.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree