Posterior Tibial Tendon Release and Stabilization

Mollie Manley

Alex Kline

Dane Wukich

Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) is a relatively common problem of middle-aged adults; however, it is relatively uncommon in younger adults, adolescents, and athletes (1, 2, 3, 4). Awareness of the condition and early diagnosis are important to prevent disability and prolonged time away from sports. Rupture of the posterior tibial tendon (PTT) results in a progressive, painful flatfoot deformity as it progresses through well-defined stages. Unlike the Achilles tendon, the PTT does not typically undergo acute rupture, and the orthopaedic literature regarding treatment in athletes and young adults is based on small case series or case reports (5, 6, 7). Idiopathic inflammation and rupture of the PTT can be a manifestation of seronegative inflammatory disease, especially when PTTD presents in younger patients (8).

ANATOMY

The tibialis posterior (PT) muscle originates proximally on the posterior surface of the tibia, fibula, and interosseous membrane. The muscle is contained in the deep posterior compartment of the leg and transitions to tendon in the distal third of the leg. The tendon passes directly posterior to the medial malleolus where the course becomes more horizontal. This is the most anterior of the three flexor tendons posterior to the medial malleolus, the other two being the flexor digitorum and flexor hallucis longus (FHL). The PTT has a broad insertion on the plantar aspect of the foot with its major insertion point attaching to the inferior navicular. Other sites of attachment are the bases of the second, third, and fourth metatarsals, all three cuneiforms and the sustentaculum tali. The PT is innervated by nerve roots L5, S1 forming the tibial nerve. The posterior tibial artery provides the blood supply; however, there is a zone of hypovascularity in the tendon approximately 4 cm from its insertion (9).

BIOMECHANICS

The primary actions of the PT are plantar flexion of the ankle and inversion of the subtalar joint. It is also vital to maintaining the integrity of the longitudinal arch. During heel strike and the flatfoot phase of the gait cycle, the subtalar joint is everted and the transverse tarsal joint is flexible. This allows the foot to adapt to the contour of the terrain, especially during heel strike. During the midstance phase of gait, the PT inverts the hindfoot, thus locking the transverse tarsal joints. This action brings the foot into neutral position of the hindfoot and increases its mechanical advantage for the toe off phase of gait. The PT controls the mobility of the transverse tarsal joints (i.e., talonavicular and calcaneocuboid) locking these joints prior to heel rise. At the beginning of toe off phase, the transverse tarsal joint becomes rigid and the subtalar joint is inverted. The rigidly inverted hindfoot and tension of the plantar fascia convert the longitudinal arch into a rigid lever to aid in toe off. The PT is also a structure that helps to maintain this arch (10). Large demands are placed on the tendon during high impact activities and running, especially in patients with a pronated foot. The peroneal tendons are the primary antagonists to inversion force and the tibialis anterior tendon antagonizes plantar flexion force.

INJURIES

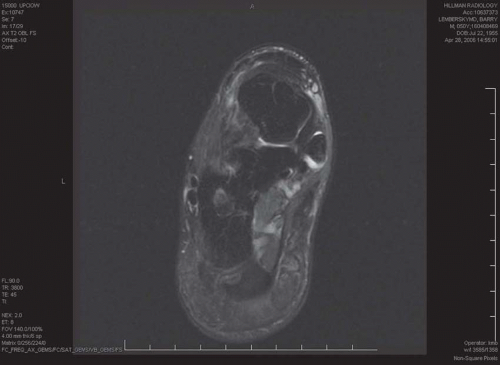

Sports related injuries to the TP tendon include those injuries common to athletics in general such as complete or partial ruptures, tenosynovitis, and overuse syndrome. Anterior dislocation of the TP superficial to the medial malleolus can occur with inversion and dorsiflexion of the foot; however, this is relatively rare (11). Patients with preexisting flatfoot deformity and hindfoot valgus are at increased risk of developing PTTD during athletic activities. Patients with tenosynovitis are typically women in their 40s to 60s with careers that require prolonged standing. They complain of pain and weakness that are increased with activity and decreased with rest and anti-inflammatory medication. Most patients with tendon rupture have a previous history of tenosynovitis, usually without a specific history of trauma. These patients develop insidious deformity, resulting in hindfoot valgus and abduction of the forefoot on the midfoot (Fig. 51.1). Patients with a ruptured PT initially complain of pain that begins medially between the navicular and the medial malleolus but eventually develop lateral pain in the region of the sinus tarsi (12). The lateral pain is due to the valgus position of the hindfoot with the calcaneus abutting the fibula, also known as subfibular impingement. Os subtibiale is a rare but reported cause of PTT dysfunction. The os subtibiale, an anatomic bony variant near the tip of the medial malleolus, can impinge the PTT in dorsiflexion and eversion (13). Magnetic resonance imaging studies have demonstrated longitudinal tears and inflammation from the os subtibiale impinging on the PTT (Fig. 51.2).

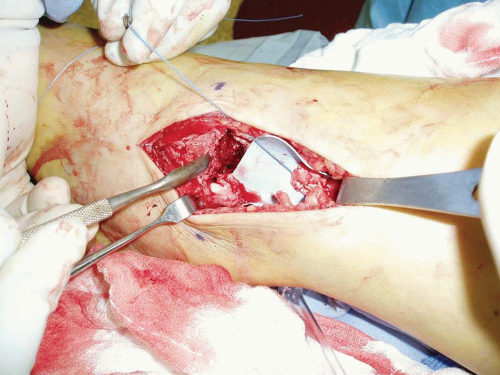

PTT pathology in adolescents and athletes is rarely discussed in the literature. Tenosynovitis and tendon laceration are the most common pathologies in these groups (2, 3, 4). Direct penetrating injury is almost always the cause of tendon rupture in this young group of patients, which is a distinction from adult disorders (14) (Fig. 51.3). A case reported by Jacoby describes an athlete without direct medial laceration who sustained an ankle sprain. Two weeks later while training under unusually high loads, the patient experienced another twisting injury to his ankle causing rupture of the PTT (15). Masterson et al. reported on three young patients who developed unilateral pes planus after old undiagnosed lacerations of the tendon. Transfer of the FHL to the distal stump of the tibialis posterior tendon achieved good results in all three cases (4). Brodsky et al. (3) reported on two teenagers who experienced closed posterior tears during athletic activities. Both patients were able to resume normal athletic activities after reconstruction using the flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendon.

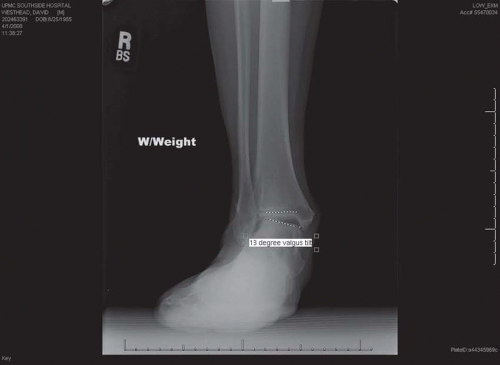

A classification system has been developed by Johnson and Strom to aid in the staging and treatment plan (16). Although it was originally three stages, Myerson expanded this classification to include a fourth (17). Stage I describes a normal alignment of the foot with pain medially around the TP tendon with inflammation. A stage II foot has a flexible hindfoot valgus with a positive “too many toes” sign (Fig. 51.4). An important finding in stage II is the ability to be able to reduce the deformity. These patients complain of weakness and are unable to do a single leg heel raise. Stage III is present when a fixed valgus deformity of the hindfoot occurs. As a result of the hindfoot deformity, the forefoot supinates to maintain a plantigrade foot. Lastly, stage IV has had long-standing PTT insufficiency with associated ankle arthritis (17) (Fig. 51.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree