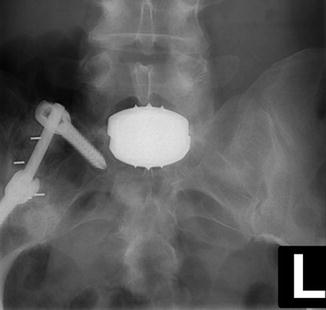

Fig. 12.1

An AP view of the left and right SI joints (SIJs) after fusion using a direct posterior approach and fixation with trans-SIJ screws. Note that the right SIJ screw was removed after successful fusion due to soft tissue irritation (permission to use photo by E. Jeffrey Donner)

Fig. 12.2

An AP view of PEEK Intervertebral Body Fusion Devices (IBFDs) in the SIJ and fixation with S1 and iliac pedicle screws joined by a rod (permission to use photo by E. Jeffrey Donner)

Fig. 12.3

A lateral view of PEEK IBFDs in the SIJ and fixation with S1 and iliac pedicle screws joined by a rod in the same patient from Fig. 12.2 (permission to use photo by E. Jeffrey Donner)

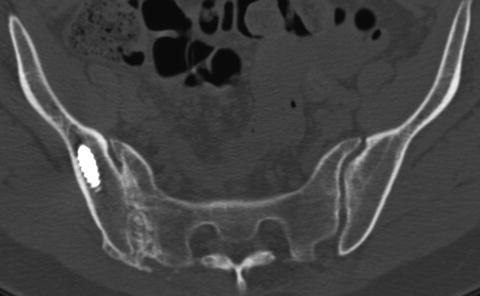

Fig. 12.4

PEEK IBFDs in the SIJ and fixation with S1 and iliac pedicle screws joined by a rod (permission to use photo by E. Jeffrey Donner)

In 1996 Donner and Browne [17] reported on a 3-year retrospective follow-up study on 18 patients (25 SIFs) who had undergone an SIF with a posterior approach with the addition of internal fixation (Fig. 12.1). There were 11 unilateral fusions and seven bilateral fusions. The average duration of symptoms was 3.25 years. There was a minimum 1-year follow-up with an average follow-up of 20 months. The indications for surgical treatment were chronic disabling SIJ pain, which failed to improve with nonoperative treatment. The pain was localized to the SIJ using CT-guided or fluoroscopic-guided SIJ injections with an anesthetic and steroid solution. Discography and facet injections were often utilized to rule out possible lumbar pathology, and if they were significant pain generators, they were also treated simultaneously. Fourteen out of the 18 patients improved from the procedure. The average overall symptom improvement is 89 % for unilateral SIJ fusions (range: 75–100 %) and 79 % for bilateral SIFs (range: 50–100 %). The average leg pain improvement was 86 %. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of posterior SIJ fusion for chronic intractable SIJ-related pain syndrome. Long-term follow-up on this study group has demonstrated durability of this procedure.

Minimally Invasive Surgical (MIS) Techniques

The most commonly utilized MIS techniques involved performing a percutaneous lateral approach and placing fixation screws across the SIJ without a fusion (as popularized by Lippitt in the 1990s) is similar to the method used for pelvic trauma, with the belief the primary cause of the patient’s pain was due to excessive instability of the joint [8]. Additional products have been introduced into the market, and these techniques primarily incorporate stabilization of the joint with a variety of screws with the addition of bone grafting techniques from the same lateral approach. All of these techniques may have their perceived advantages, but some of the disadvantages based on the author’s experience primarily include a limited ability to visualize and assure adequate removal of the articular cartilage as well as sufficient decortication of the subchondral bone which is often very dense on the iliac surface. Both of these limitations may limit the ability to obtain a reliable boney fusion. This issue is emphasized by Dr. Christopher Shaffrey in a 2013 editorial regarding SIJ stabilization wherein he states: “concern with this implant [fusion rods] is whether the porous plasma spray coating on the implant actually results in bone growth across the SIJ or only serves as a stabilizer. If true fusion does not result, deterioration in the clinical result could occur over time” [18]. Furthermore, the majority of the MIS techniques are performed with a fluoroscopic-guided lateral approach which on the surface appears minimally invasive when visualizing the 2–3 cm incision, but in reality there is a significant amount of deep tissue disruption when making multiple passes with a variety of instruments in multiple locations through the gluteus muscles and in close proximity to their accompanying neurovascular bundles.

Author’s Experience with Minimally Invasive SIJ Fusions

Having performed the majority of these open procedures and MIS techniques, the author prefers performing a less invasive procedure. This procedure accomplishes the principle mission of thoroughly removing the painful cartilage, decorticating the subchondral bone, and obtaining a boney fusion of the SIJ. This is performed by directly accessing the articular portion of the joint through a posterior inferior access “window” in the plane of the SIJ with a minimally invasive approach located above the sciatic notch and below the PSIS (Figs. 12.5, 12.6, and 12.7).

Fig. 12.5

Shows a lateral view illustrating the posterior inferior access region (permission to use photo by Springer illustration (permission to use duplicate image in book by G Sartorius))

Fig. 12.6

Shows a posterior view illustrating the posterior inferior access region (permission to use illustration by Christopher Donner)

Fig. 12.7

Drawings and photo illustrating the cartilaginous portion of the SIJ. Courtesy and copyright of ZYGA TECHNOLOGY, Inc. (permission to use photo by Zyga Technology, Inc.)

Advantageously, this approach allows conversion of an MIS technique to a mini-open technique where direct visualization of the joint surfaces is possible if the surgeon so desires or to an open procedure if the situation necessitates greater visualization and access to the joint, ligaments, or surrounding neurovascular elements.

It is also the author’s opinion, based on orthopedic principles and analogous to other pathologic orthopedic joint conditions, that the main pain generator from a dysfunctional or degenerative SI joint is related to disruption, injury, or degeneration of the articular surface of the joint and not gross instability. Based on this hypothesis, the surgeon’s attention should be directed toward removal of the painful degenerative cartilage followed by fusion and fixation. This is typical of the approach and orthopedic logic applied to most other degenerative joints where a joint replacement is not available or not the best-proven option [12, 19].

The unique anatomy of the SIJ is well described in Chap. 3 by Dr. Michael Rahl. Basically, the joint has been classified as both diarthrodial, based on satisfying the criteria of having a hyaline articular surface, surrounding capsule and synovium, and supporting ligaments, and more specifically as amphiarthrodial since there is very limited motion of the joint [20]. The motion itself is described as nutation where there is a sliding, rotational movement of the joint between the articular surfaces which has many matching undulations constrained by strong ligaments. Another unique characteristic of this vertically oriented joint is its keystone type configuration, where the wedge-shaped sacrum is situated in the middle of the arch created by the ilia of the pelvis [1]. A majority of the body weight is transmitted through each SIJ when on a single leg stance, and therefore, the movement of the joint within this unique interlocking and constrained anatomy is critical to understanding the pathologic degenerative process and clinical symptoms. These same anatomic features and movements help create high contact stresses which may lead to early degeneration and pain especially if there is trauma or a malalignment of the sacroiliac undulations which can occur with SIJ traumatic injuries such as with motor vehicle accidents or through normal activities such as lifting and jumping. Cartilage injury in other joints has been demonstrated to induce chondrocyte apoptosis [21–23]. Even a small amount of malalignment may markedly increase the contact stresses across the SI joint surfaces, analogous to malalignment of the ankle joint where the stress per unit area increases as the total contact area decreases. The malalignment of the matching undulations may lead to a decrease in normal contact area similar to what has been identified with even 1 mm of talar displacement in the ankle mortise, which leads to a 42 % reduction in the contact area between the tibia and talus [24]. According to the author’s experience, patients will often describe severe pain with the sensation that the joint is “out of place” when a malalignment occurs. And when realigned, either spontaneously or with the assistance of a manipulation by a chiropractor or physical therapist, these patients describe the feeling as though the joint “pops back into place” often followed by relief of the pain. The long-term sequela of malalignment of the SIJ is analogous to what is observed when an ankle fracture dislocation is not anatomically aligned during ORIF and early degeneration of the joint and pain develops [12].

Obesity is another major risk factor which adds significant loads and stresses to weight-bearing joints, further increasing the chance of degeneration, pain, and dysfunction [25, 26]. In addition to this, more patients are undergoing longer instrumented fusions in the lumbar spine which typically end at the sacrum which creates a large lever arm and markedly increased stresses across the SIJ elucidated by multiple clinicians through radiographic surveys as well as biomechanical analysis [4, 5, 27, 28].

The author has extensive experience fusing hundreds of SI joints through a direct open posterior procedure over the course of 20 years and rarely visualized movement of the SI joint with mechanical testing. Some joint motion was observed after removal of the PSIS and posterior interosseous ligaments (ISL). Further removal of the joint surfaces led to mechanical instability, but stability was restored by impacting bone graft with off-label intervertebral interbody cages into the joint space followed by sacroiliac screw fixation across the joint. The surgical technique involves removing as much of the joint surfaces as possible, similar to the orthopedic concepts used for joint fusions such as the subtalar joint, in order to eliminate the painful abnormal articular cartilage but also in order to obtain a large fusion surface area for long-term stability and pain relief [12].

The above-described approaches disrupt significant dorsal ligaments, and therefore, it is prudent to utilize a technique which preserves the integrity of the ligamentous complex in order to enhance stability for obtaining a fusion. The vast ISL is the strongest of the SIJ-supporting ligaments providing for major multidirectional structural stability. Not only is the ISL the strongest SIJ-supporting ligament, but it also has the most extensive bony origin and overall volume of all SIJ ligaments [20, 29].

A surgical technique, which significantly disrupts the ISL, may lead to further joint instability than techniques, which attempt to spare or minimally disrupt it. This may be one of the reasons for Dr. Smith-Petersen’s findings of when “[a] wedge [is] driven in between the posterior crest of the ilium and the dorsum of the sacrum [it] would tend to spread the joint and consequently would not render the local condition in the joint as favorable for bony ankylosis as an operation that aims to eradicate the joint. I have seen three cases in which the wedge operation was performed. The results were far from satisfactory [30].” Perhaps his unsatisfactory results were due to a gross violation of the ISL which may have consequently compromised the stability of the joint and therefore the ability of the joint to fuse; or, rather, as Dr. Smith-Petersen implies, the failure to resolve the patient’s condition may lie with the increased distance the fusion must overcome given the distraction of the joint or the fact that the joint surfaces were insufficiently prepared.

As evidenced by a 2013 study conducted by Dr. Stefan Endres in Germany on 19 patients who had prior multilevel lumbar or lumbosacral fusion procedures, the patients’ VAS scores improved 30 % from an 8.5 pre-op to a 6 at an average 13.2-month follow-up following an extra-articular distraction interference arthrodesis of the SIJ with an average length of stay of 7.3 days while obtaining a fusion rate of 79 % [31]. While this represents an improvement in the patients’ condition, the author’s experience with techniques which specifically address the articular surfaces of the SI joint and provide adequate fixation yields a much greater amount of pain relief with significantly shorter duration of hospitalization.

Over time, it was recognized this procedure could be performed less invasively through a small incision below the PSIS and above the sciatic notch while not removing the PSIS and interosseous ligaments. Following cartilage removal from this limited exposure, local autogenous bone graft may still be obtained from the “noncontact” portion of the inferior PSIS (the posterior inferior overhang of the PSIS), which may then be packed into the decorticated joint along with a variety of sized interbody spacers. The technique is further augmented with trans-sacroiliac screw fixation under fluoroscopic guidance with neural monitoring. The author was able to identify the advantages of this technique by witnessing quicker recovery and less pain than the traditional more extensive open posterior approach previously described. The remainder of this chapter will be dedicated to describing the steps of this specific minimally invasive technique and the important anatomy and technical issues which need to be recognized in order to achieve the best fusion and clinical result while avoiding complications.

Posterior Inferior Fusion-Minimally Invasive Surgical (PIF-MIS) Technique of the SIJ

Figures 12.5, 12.6, and 12.7 illustrate the relevant anatomy for the surgical approach to the posterior inferior articular access to the caudal end of the “boot-shaped” articular cartilage portion of the joint which also allows access to the cephalad arm of the joint and subtotal removal of the articular surfaces across the deepest point of the extra-articular recess. The surgical approach utilizes the standard prone position on the translucent operating room table to allow intraoperative fluoroscopy. After the patient is prepped and draped in the usual aseptic manner and a sterile covered C-arm is positioned in the AP plane, the inferior portion of the joint is identified above the sciatic notch and a metallic instrument is placed on the skin over this anatomic landmark just inferior to the PSIS. A lateral view is then obtained with the sciatic notches and hip joints overlapped to obtain a true lateral image, and the direction of the probe is aligned parallel to the caudal articular arm of the joint, and the C-arm image is adjusted so that the probe is perpendicular to the floor (Fig. 12.8).