Chapter109 Posterior Cruciate Ligament Retention in Total Knee Arthroplasty

Analysis of the available data is limited by two issues. First, the implants we now use are frequently different in both big and small (but perhaps no less important) ways from those reported on in most of the long-term follow-up studies. Second, these longer-term studies may reflect a significantly different patient population than that currently presenting for knee replacement. In the early decades of knee arthroplasty surgery, some series reflected as many as half of patients having inflammatory (most commonly rheumatoid) arthritis.35 Young age, large size, primary or secondary degenerative osteoarthritis, and what were considered high physical activity demands generally were not thought to be ideal indications for TKA. Concerns about implant longevity, as well as a relatively higher complication rate and fear of early failure, led many surgeons to delay arthroplasty of the knee until more advanced disease was present, along with a lower likelihood that the patient would stress the implant construct.

PS designs (discussed in Chapter 11) have been suggested to offer easier correction of deformity without concern for obtaining appropriate tension on the PCL, a more conforming polyethylene surface that results in decreased polyethylene wear, and more reliable rollback of the femur on the tibia in flexion.58 Proponents of the PS design note the more widespread clinical usefulness in that it can be used in knees without a PCL,36 as well as the potential benefit of avoiding late posterior instability from PCL rupture, which has been reported in osteoarthritic patients49 and in those with inflammatory arthritis.41,45

Proponents of CR3,4,7,14,28 have suggested that advantages include preservation of an important central stabilizing ligamentous structure, transfer of stress to a functional ligament rather than a mechanical structure with subsequent reduction in wear and fixation stress, more consistent preservation of the joint line,29 improvement in stair climbing ability,4 and greater conservation of bone. In addition, problems that appear to be unique to PS designs—patellar clunk and post breakage and wear—are absent from CR designs.42,44 Finally, the concept of simply resurfacing the joint and maintaining as much of the normal structures structure as possible is a philosophically appealing one, and indeed clinical data support both the quality and the longevity of the CR TKA.

Results of PCL-Retaining TKA

Long-term series of many different CR TKA systems demonstrate excellent longevity and clinical results.* These results reflect 3 decades of evolving implant designs, which have corrected some of the problems noted in previous implant designs and materials and have reflected improvements in surgical technique and understanding of the technical requirements of implanting a knee that retains the PCL. These include improved patellofemoral design characteristics; better understanding of modularity, locking mechanisms, and the adverse effects of back-side wear; improved understanding of the relationship between implant surface kinematics and normal knee function and motion requirements; and improved manufacturing and sterilization of polyethylene. Although earlier studies of older-generation CR systems frequently showed 10-year survivorship of 90%, newer-generation systems have demonstrated improved 10-year survivorship to 96% to 100%.†

Aseptic loosening as a mode of failure is relatively rare in both CR and PS TKA, with no clear advantage seen for either type.21,37,60 However, a relative weakness in much of the literature is that it reflects single surgeon series (frequently performed by the implant designer or in an academic setting by individuals who perform high volumes of TKA) and so is less likely to give a balanced view of a particular knee’s performance, hence the importance of registry studies and large database reviews. The few of these that are available do show differences in outcome by implant type.

A study of all primary TKAs performed at the Mayo Clinic over a 22-year period noted several trends.54 Overall survivorship of 84% at 15 years was a significant improvement from the 69% noted in an earlier study from the same institution. Significant risk factors for failure included young age, male gender, noninflammatory arthritis, and the use of metal-backed patellae. Of note with regard to survival of CR versus PS implants, the 10-year survival rate of the CR TKA group was 91% as compared with 76% with posteriorly stabilized designs.

Additional multicenter investigational cohort studies support this finding. Heck and associates69 reported a survey of 563 TKAs performed by 43 community surgeons and found that one of the factors related to maximal performance was PCL retention; in addition, the annual reoperation rate was 0.43 per year with CR knees as opposed to 0.51 in the PS design. Both studies indicated that CR implants have better long-term survivorship than PS implants.

Functional Comparisons

Several studies claim that sensitive function measures show better performance in deep flexion for the CR knee23; however, no substantial body of evidence indicates that sacrifice, substitution, or retention leads to consistently “better” knee function.37,38 Multiple studies have noted no difference between the two in ultimate range of motion or in traditional knee outcome ratings. Studies comparing patients with a CR TKA on one side and a PS on the other have failed to reveal a persistent patient preference for one TKA type over the other.9,13,60,61

Kinematics

In the normal knee, the PCL serves several functions. It guides rollback of the femoral condyles on the tibial plateau during flexion, thereby allowing the posterior condyles to “clear” the posterior aspect of the tibia in high degrees of flexion and improving the mechanical efficiency of the extensor mechanism.3 From the standpoint of stability, it prevents posterior subluxation of the tibia on the femur in flexion, while playing a strong secondary role in varus/valgus stability with the knee in flexion.

The history of knee arthroplasty is replete with studies evaluating the kinematic performance of total knee replacement in vivo. Multiple techniques have been used, and multiple claims promoted.* Indeed, controversy continues regarding the ability of the surgeon to successfully preserve the PCL in a way that is clinically meaningful. Several authors have claimed that maintaining PCL function following TKA is impossible, and that the kinematic demands of PCL retention require design considerations contrary to maximizing implant longevity.36

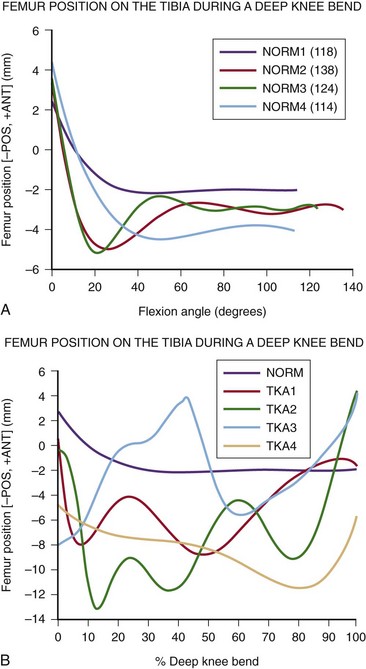

In the late 1990s, Komistek, Dennis, Steihl and coworkers studied in vivo knee performance in flexion by measuring rollback of the femur on the tibia in PS and CR knees via digital analysis of video fluoroscopy. Their initial studies showed a consistent pattern of anterior translation of the femur on the tibia in flexion in all CR knees studied.25–27,46,62 This finding was the reverse of the expected rollback of the femur and was termed paradoxical motion (Fig. 109-1A and B). These reports implied that no evidence suggested that the retained PCL was functioning in its expected role. It should be noted that these studies did not describe the surgical technique employed or the type of CR knee used. Yet the same group subsequently demonstrated that preservation of the PCL, combined with appropriate implant design, preserves femoral rollback in a study of an unselected group of CR TKAs performed by a single surgeon using a standardized technique with the use of a specific implant design, specific instrumentation, and a specific technique to adjust PCL tension.12 In this group of 20 patients, all but one demonstrated essentially normal patterns of femoral rollback. More recent studies of the same implant design, implanted by three different surgeons using differing techniques,40 revealed consistent rollback in all patients, thus indicating that these findings are not surgeon dependent, but rather are influenced by component design and technique. Results strongly implied that routine PCL preservation could be accomplished with functionally appropriate tensioning.

Additionally, Banks and associates6 used three-dimensional kinematic assessment with fluoroscopy in a group of total knee replacements with intact PCLs that had essentially normal axial rotation and condylar translation; those with a post-and-cam substitution and no PCL had the smallest in vivo range of rotation and translation.

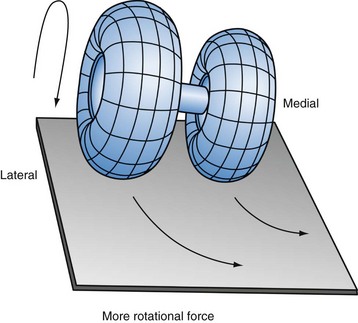

Of course, the articular surfaces must be designed to be compatible with normal femoral rollback. The “normal” rollback in the CR knees studied by Komistek and colleagues featured differing femoral condylar radii (Fig. 109-2). The differential radii allow the femoral component to roll posteriorly to a greater degree on the lateral side, as in the normal knee.12,40 On the tibial side, a slightly flattened design in the sagittal plane takes advantage of the retained ligament, allowing the femur to both roll back and rotate in a relatively normal fashion. At the same time, significant congruence in the frontal plane allows stress in the polyethylene to be minimized, thus reducing long-term wear. It is clear that the geometry of articular surfaces affects motion-bearing surface strain and wear.47,51

PCL-Retaining versus PCL-Substituting Designs

Clinical Comparisons

Range of Motion

Numerous studies comparing CR and PS TKA have found no differences between the two in ultimate range of motion.9,19,28

Functional Studies

The theoretical advantage of improved proprioception attained by retaining the PCL was claimed by Warren and colleagues,66 but most investigators have reported no difference in proprioception between the two types of TKA.18,61 This may be due in part to the fact that the PCL in osteoarthritic knees has been shown to be more commonly histologically abnormal in comparison with control groups,39 which may render the PCL less able to provide proprioception.

Although early studies demonstrated more normal stair climbing patterns and improvement in CR TKA,4 several studies have shown no difference.28,60 Conditt and coworkers23 found poorer functional scores on squatting, kneeling, and gardening in patients with PS knees. They suggested that the PCL offers better functional capacity in higher-demand activities, especially those involving deep knee flexion. Unfortunately, like so many studies, this represents the results of one surgeon using one specific technique and one specific CR and PS implant system; thus, it cannot be thought to validate the claim that these findings can be generalized to other implants, surgeons, or patient groups.

Bilateral Studies

Numerous studies have compared patients with a CR TKA on one side and a PS TKA on the other.9,13,21,60 These studies have not demonstrated a persistent patient preference for one TKA type over another.

Polyethylene Wear

The earliest CR designs featured polyethylene of relatively poor quality, resulting in higher rates of wear. Problems included the use of excessively thin and heat-pressed plastic, as well as the addition of calcium stearate. Over time, other manufacturing and sterilization techniques were shown to affect wear. These problems have since been addressed, and increased wear rates have not been seen with newer designs. However, poor soft tissue balancing in a CR TKA can result in tightness of the PCL in flexion, which can lead to posterior polyethylene wear.64,69 Problems of instability and post dislocation can be seen in PS TKA as well if the soft tissues are not balanced.58 This delineates the importance of soft tissue balancing, no matter what type of TKA is performed.

Correction of Deformity

Proponents of PS TKA have argued that larger deformities present difficulty with soft tissue balancing and are more easily balanced with a PS TKA. Although this can certainly be the case, some authors have used CR TKA in the setting of significant preoperative deformity and have had good results.11,31 If the deformity is severe enough, flexion/extension mismatches or collateral ligamentous insufficiency often necessitates that even PS TKA is insufficient, and that more constrained knee replacements or even hinged TKA is necessary (Figs. 109-3A and B and 109-4A–C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree