Posterior Approaches to the Hip

Bryan P. Springer

Key Points

Introduction

The basic fundamentals of total hip arthroplasty begin with the surgical approach. A complete understanding of anatomy and the surgical approach is critical to a successful outcome. It is clear that one surgical approach may not satisfy all patients, and different situations may require an alternative approach, such as extensile approaches or osteotomies. Although most surgeons choose a surgical approach based on experience and training, it is important that they be familiar with multiple exposures.

Much debate and controversy have arisen in the past decade regarding the ideal surgical approach. Surgical approaches that require specialized instruments and even modified implants have been developed. Minimally invasive surgery gained popularity by promoting less muscle damage, faster recovery, and improved clinical outcomes.1–4 To date however, little evidence exists to support these claims, and concern continues regarding associated complications.5–9 The direct anterior approach is now gaining attention and is touting many of the same benefits of minimally invasive surgery. Likewise, however, few data currently show the superiority of one approach over another.

This chapter focuses on the posterior approach to the hip for total hip arthroplasty. The purpose is to review the historical background, pertinent anatomy, and surgical techniques. In addition, extensile exposures and current controversies regarding the posterior approach are reviewed.

Historical Background of the Posterior Approach to the Hip

This procedure was initially described as a surgical approach to the hip joint for the treatment of infection and war wounds. Bernhard von Langenbeck is credited with the first description in 1867 of what he termed “the longitudinal incision to the hip.”10,11 With the hip in a flexed position, he fashioned an incision “from above the ischiadic notch to the middle of the greater trochanter that reaches the joint passing between the bundles of the gluteal muscles.” Langenbeck applied this surgical approach for resection of the femoral head (what he called “hip joint resection”) and used hooks or “ball-screw” devices to extract the femoral head after cutting the ligamentum teres.

Kocher modified Langenbeck’s approach by extending it in a caudal direction. He stated, “The incision is an angular (or curved) one, extending from the base of the outer surface of the great trochanter upwards to its anterior superior angle, and from thence obliquely upwards and backwards in the direction of the gluteus maximus.”12 Division of the gluteus maximus tendon and anterior reflection of the gluteus medius and minimus were followed by internal rotation of the hip and detachment of the piriformis and the other short external rotators. Regarding this approach, Kocher said that “it is a further development of Langenbeck’s method by the oblique incision.”

Melham and associates, in their 2000 article entitled “Hyphenated-History: The Kocher-Langenbeck Surgical Approach,” stated as follows:

“The Kocher-Langenbeck surgical approach continues to be widely used today by both orthopaedic trauma surgeons and reconstructive hip surgeons. By many it is considered to be a workhorse approach for posterior wall fractures of the acetabulum, femoral neck fractures treated via hemiarthroplasty, and total hip replacement. The durability of an idea born in the nineteenth century on the battlefields of Europe and refined in the operating theaters of Bern is indeed impressive. If he were around today, Kocher’s humility would certainly be challenged by the widespread use of his particular portion of hyphenated-history.”13

Dr. Alexander Gibson and Dr. A.T. Moore are largely credited with popularization of the posterior approach, often referred to as the “Southern approach,” which is used today for total hip arthroplasty.14,15 Although their initial description of the posterior approach has undergone several modifications since its initial description in 1950, the fundamentals of the exposure remain largely intact. Many of the modifications involve different placement and size of the skin incision, preferential detachment of the short external rotators, and posterior capsular repair. The usefulness of this approach can be appreciated by the diverse surgical procedures that can be performed through the posterior approach. These include hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty of the hip, hip resurfacing, open reduction and internal fixation of acetabular fractures, and arthrotomy and drainage of the hip joint for infection.

Surgical Anatomy of the Posterior Approach to the Hip

Muscular Anatomy

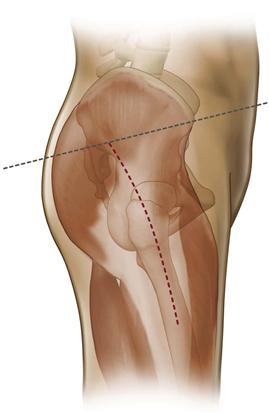

The muscles covering the posterior aspect of the hip joint are divided into deep and superficial layers. Henry described the outer layer as the “deltoid” muscle of the hip, similar to the deltoid of the shoulder.16 This layer consists of the gluteus maximus, the fascia lata, and the tensor fascia lata, which together form the outer sheath of the hip musculature (Fig. 19-1).

Figure 19-1 Picture demonstrates the “outer sheath” of the hip joint muscles, including the gluteus maximus, fascia lata, and tensor fascia lata.

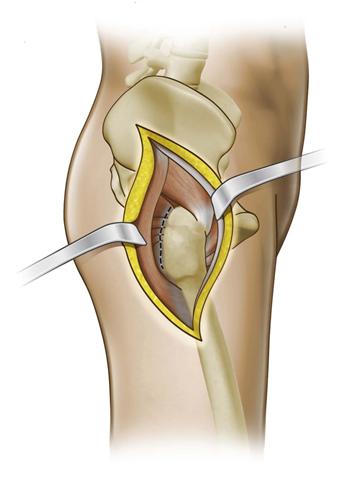

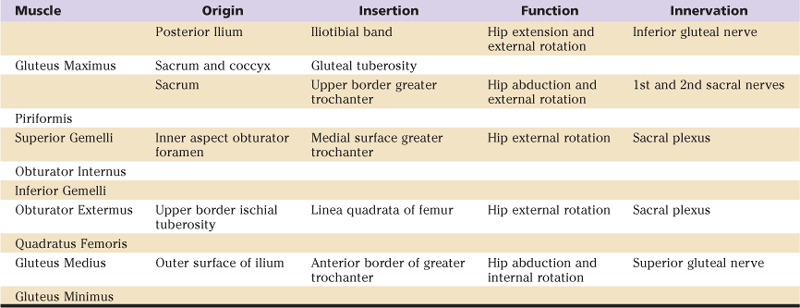

The deep layer of the hip encountered during the posterior approach consists of the short external rotators. From cephalad to caudad, they include the piriformis, the superior gemelli, the obturator internus, the inferior gemelli, the obturator externus, and the quadratus femoris (Fig. 19-2). The musculotendinous insertions of the gluteus medius and minimus insert at the tip of the greater trochanter and are not disturbed during the posterior approach to the hip. Table 19-1 lists the origins and insertions of pertinent muscles of the posterior approach, along with their neurologic innervation.

Figure 19-2 The “deep layer” of the hip includes the short external rotators: piriformis, superior gemelli, obturator internus, inferior gemelli, obturator externus, and quadratus femoris.

Table 19-1

Anatomic, Functional, and Nervous Innervation of Posterior Structures of the Hip

Neurovascular Anatomy

All neurologic and vascular structures pertinent to the posterior approach to the hip enter the hip from the pelvis through the sciatic notch. The piriformis tendon defines the pathway for the neurovascular anatomy of the hip. Ten structures enter the hip through the sciatic notch, passing superior or inferior to the tendon to supply their given muscles. Box 19-1 lists the neurovascular structures of the hip relative to the piriformis tendon.

The superior gluteal nerve and artery enter the pelvis above the piriformis to supply the gluteus medius and minimus muscles. Although not frequently encountered during the posterior approach to total hip arthroplasty, the superior gluteal artery and nerve tether the gluteus medius and minimus musculature to the ilium, preventing complete mobilization of these muscles and limiting exposure of the ilium. Damage to the superior gluteal nerve can lead to denervation of these muscles, resulting in abductor muscle dysfunction. Injury to the superior gluteal artery can result in brisk pelvic bleeding and is difficult to control because the artery may retract into the pelvis during injury, making identification and ligation difficult. In these circumstances, an extraperitoneal approach to the pelvis may be required to control the internal iliac artery, which is the feeding branch to the superior gluteal artery.

The inferior gluteal nerve and artery reach the hip below the piriformis tendon. They provide the neurovascular supply to the gluteus maximus. Because they enter the muscle almost immediately, they remain well medial and are not encountered during a routine posterior approach to the hip.

The sciatic nerve enters the hip below the piriformis and traverses between the superficial (gluteus maximus) and deep (short external rotators) layers of the hip. During the posterior approach to the hip, it is generally protected by the muscular flaps of the short external rotators but may be injured during errant posterior retractor placement, surgical reduction and dislocation of the prosthetic hip joint, or excessive leg lengthening.

Surgical Technique

Patient Positioning

Figure 19-3 Patient positioning before total hip arthroplasty.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree