Fig. 37.1

Vesicular eruptions of patient with PAN. The eruptions are more frequent in upper and lower extremities than trunk

Fig. 37.2

Vesicular eruptions of patient with PAN. The eruptions are more frequent in upper and lower extremities than trunk

There is no known etiology for PAN, although numerous infectious agents (e.g., hepatitis B and C, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus) have been implicated in the pathogenesis. The association of PAN with HBV is particularly strong. PAN may develop within the first 6 months of an HBV infection as a result of immune-complex formation [4].

Diagnosis of PAN requires the integration of clinical, angiography, and biopsy findings. The ACR classification criteria of PAN are commonly used with 82.2 % of sensitivity and 86.6 % of specificity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are negative in PAN. The renal, hepatic, and mesenteric vessels are the most frequently involved vessels in PAN. The typical angiographic appearance includes segments of arterial stenosis alternating with normal or dilated artery areas, smooth tapered occlusions, and thrombosis. The dilated segments have saccular and fusiform aneurysms [5, 6] (Figs. 37.3 and 37.4).

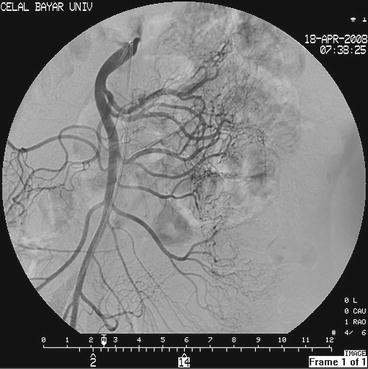

Fig. 37.3

The superior mesenteric artery angiography of the same patient shows the millimetric aneurysms

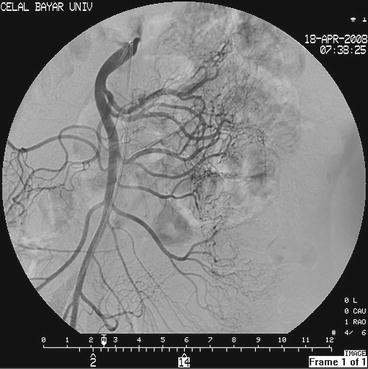

Fig. 37.4

The renal artery angiography of the same patient shows the millimetric aneurysms

Differential Diagnosis

A cutaneous form of polyarteritis, affecting predominantly the lower extremities, is distinguished from systemic PAN by its restriction to the skin and to the neurological and osteo-muscular systems and lack of visceral involvement and benign course. Skin biopsy of a typical lesion is usually performed to make an accurate diagnosis of cutaneous PAN.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree