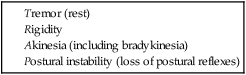

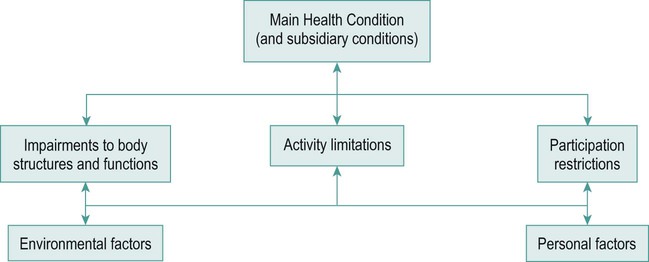

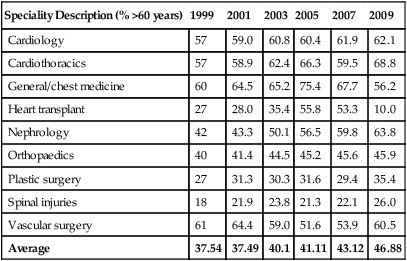

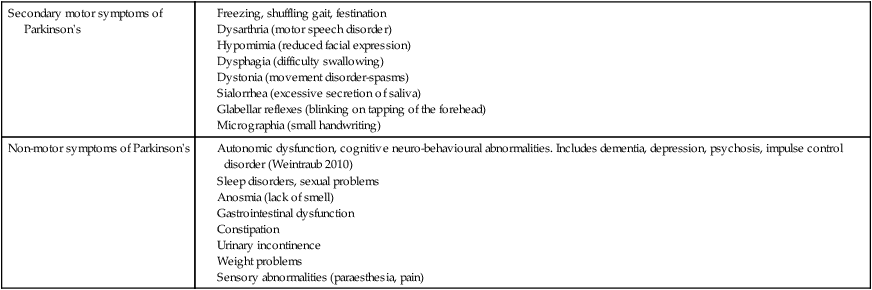

• between 60 and 75 years = young old; • between 75 and 85 years = old; • those older than 85 years are considered the frail older population. The variations between the populations in each age band require different approaches when considering the physical, psychological and social needs of people within the groups (DH 2001). Thinking that the ageing population is only of concern to physiotherapists specialising in older people is unrealistic. The percentage of people aged above 60 years admitted to clinical specialities in a Sheffield hospital over a ten-year period (Table 24.1) illustrates a pattern of overall increase in the numbers of older people. It is important that these people receive the same level of service and care as anyone else, irrespective of age. Table 24.1 Percentage of people aged over 60 years admitted to Northern General Hospital, Sheffield Parkinson’s is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system; it is the most common disorder of the basal ganglia and the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the UK after Alzheimer’s disease (Jones and Playfer 2004). The incidence increases with age and has no currently known cure. The condition was described first as ‘the shaking palsy’ in 1817 by Dr James Parkinson, whose clinical description identified both the main motor symptoms and non-motor symptoms (Tables 24.2 and 24.3; adapted from Jankovic 2008: 368). The main area of basal ganglia dysfunction appears to stem from the loss of dopamine-producing cells in the substantia nigra, causing difficulty in the initiation of movement (internal cueing mechanism). Table 24.3 Secondary motor and non-motor symptoms (Adapted from Jankovic 2008.) There are several forms of akinesias: • Bradykinesia (slowness in movement performance or loss of spontaneity of movement) – is the most characteristic feature of Parkinson’s, although the pathophysiology has not been fully identified. It is thought to result from a reduction in normal motor cortex activity facilitated by a reduction in dopaminergic function (dopamine deficiency levels). The slowness may be demonstrated through difficulty with planning, initiating, executing and performing sequential and simultaneous tasks, and loss of fine motor control. If there is a swallowing impairment, presentations of bradykinesia might include drooling, loss of spontaneous movements and gesturing. • Hypokinesia – a decrease in amplitude may, for example, account for lack of arm swing during walking, loss of facial expression and reduced blinking. Combinations of TRAP (tremor, rigidity, akinesia, postural instability) can lead to secondary motor symptoms. A classic one is the ‘Simian’ posture where the spinal curvature results in a flattened lumbar lordosis, rounded shoulders and a poking chin (hyperextended cervical spine). The consequent forward flexed upper body results in the ‘ape-like’ posture. Examples of secondary motor and common non-motor symptoms are tabulated above (Table 24.3). Currently, no reliable test exists for Parkinson’s so diagnosis is determined through the history and clinical signs of at least two of the four cardinal motor symptoms described earlier using the UK Brain Bank Criteria and investigations (scans) (NICE 2006). Parkinson’s is the most common presentation within a collection of motor system disorders known as ‘Parkinsonism’ (Table 24.4). The various disorders can be identified using positron emission tomography (PET) and structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning. They are also referred to as ‘Parkinson’s Plus’ as they involve a wider area of the nervous system than idiopathic Parkinson’s (SIGN 2010: 11–13). Table 24.4 Parkinsonism or ‘Parkinson’s Plus’ syndromes The ‘ascending hypothesis’ of idiopathic Parkinson’s conceptualises a pathological progression from the lower brainstem (pre-clinical stage) to the midbrain (substantia nigra clinical stage) and cortex (end-stage) (Braak et al. 2003; Yanagisawa 2006). Extra-pyramidal system dysfunction leads to the loss of the internal ‘go’ setting, essential for movement initiation that becomes evident after the pre-clinical stage. Parkinson’s is classed in various ways. The most common method is by severity according to the (modified) Hoehn and Yahr scale (1967), categorising people along a continuum from asymmetry at Stage 1 to Stage 5 palliation. Physiotherapy referrals usually occur when signs of poor balance develop and possibly a fall from Stage 3 onwards. MacMahon and Thomas (1998) have provided a clinical staging classification, allowing for periods of deterioration during illness, but regaining the ability on recovery. Details of both these can be read in the Parkinson’s Professional Guide (PDS 2007). In light of evolving information regarding the pre-clinical development of Parkinson’s, Stern et al. (2012) have proposed the following phases to reflect the progress of the condition (Table 24.5). Table 24.5 Phases of development in Parkinson’s (Stern et al. 2012) A cluster analysis of presentation at diagnosis has provided detail according to a person’s age, cognitive state (presence of dementia or not) and symptom dominance (van Rooden et al. 2010). The four subtypes of Parkinson’s are identified below. • Early disease onset (25%) – longest duration until death, delay before falls or cognitive decline. • Tremor dominant (31%) – same life expectancy, falls history and hallucinations as non-tremor dominant. • Non-tremor dominant (36%) – strong association with cognitive impairment (Lewy body pathology). • Rapid disease progression without dementia (8%) – often tremulous onset in older people, early depression, midline symptoms, increased mentation, freezing and activities of daily living (ADL) sub-scores according to Part I and II of the UPDRS. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO 2001) offers a model for consideration of multiple impairments, relating them to domains that guide assessment, goal-setting and treatment-planning (Figure 24.1). Impairments often impact on activities of daily living and how the person can participate in societal roles in later life (Izaks and Westendorp 2003), and the ICF framework considers issues in context. For example, environmental (physical and attitudinal) and personal (medication, support) factors which can act as barriers or facilitators in the analysis and subsequent planning of appropriate intervention. Consideration of the target level (whether an impairment, activity or participation issue) ensures that therapeutic management meets the current status and needs of the individual. An appreciation of how people live with ongoing (a set of) conditions using such a bio-psychosocial and partnership approach to practice is key to achieving person-centred management. Prior to physical assessment, consider the following: • Consent and confidentiality. People within these groups (older adults and people with Parkinson’s) may fall into the category of ‘vulnerable adults’ and, as circumstances alter over time, their needs and support systems will change. Consent may have to be elicited differently if, for example, speech deteriorates in a person with Parkinson’s or if an older person has a stroke and verbal communication is no longer reliable. Sometimes tensions arise between the individual’s rights and the professional or organisation’s responsibility to that individual or the well-being of the family. Examples include dealing with confused individuals at risk of injury who insist on returning home or a struggling carer whose health is at risk yet refuses the help of strangers in their house. As long as the person has capacity to understand risks and take responsibility for them, the choice is theirs. • Ethics and law need considering, especially relating to end-of-life decisions or when people have reduced mental capacity requiring full discussion with family and team (Dimond 2009). • Confidentiality. Awareness of suspected elder abuse or a more serious underlying medical problem is important. Ensure that issues to be discussed outside of the immediate ward/home environment receive the person’s consent first and only then reveal information relevant to the consultation (Whiddett et al. 2006). • Recognising patterns of health and illness. The relationship between age and disease lies along a continuum making it difficult to distinguish between them (Izaks and Westendorp 2003). For example, postural changes, stiffness and restricted activity are so often seen as a part of ageing that the rigidity and bradykinesia of idiopathic Parkinson’s is missed. Also be aware that people living with chronic illness continually shift their perspective over time between one of illness and one of wellness (Paterson 2001). Intervention for these variations requires the skill of a different professional (health or social) depending on the manifestation of symptoms. Appropriate questioning allows the therapist to focus on the main presenting problem(s) (Box 24.1). Depending on their own experiences and those of people they know, a person may make out they can do better or are worse than you know them to be. For example, if a person is falling a lot at home and during a hospital admission are afraid a decision they cannot cope at home will be made, they may make out they could and are doing a lot for themselves at home. Work with colleagues (e.g. occupational therapists or nurses) to review if the information has been corroborated by friends and family. Alternatively, if someone has fallen and is afraid of returning home, they may seem reluctant to progress in therapy. Although challenging, analysis of such behaviour assists decision-making for a supportive/empathetic or firm tactic, or both.

Physiotherapy management of Parkinson’s and of older people

About ageing

Speciality Description (% >60 years)

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

Cardiology

57

59.0

60.8

60.4

61.9

62.1

Cardiothoracics

57

58.9

62.4

66.3

59.5

68.8

General/chest medicine

60

64.5

65.2

75.4

67.7

56.2

Heart transplant

27

28.0

35.4

55.8

53.3

10.0

Nephrology

42

43.3

50.1

56.5

59.8

63.8

Orthopaedics

40

41.4

44.5

45.2

45.6

45.9

Plastic surgery

27

31.3

30.3

31.6

29.4

35.4

Spinal injuries

18

21.9

23.8

21.3

22.1

26.0

Vascular surgery

61

64.4

59.0

51.6

53.9

60.5

Average

37.54

37.49

40.1

41.11

43.12

46.88

About parkinson’s

Secondary motor symptoms of Parkinson’s

Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s

Akinesias

Postural instability

Diagnosis

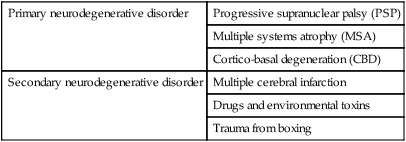

Primary neurodegenerative disorder

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

Multiple systems atrophy (MSA)

Cortico-basal degeneration (CBD)

Secondary neurodegenerative disorder

Multiple cerebral infarction

Drugs and environmental toxins

Trauma from boxing

Neuropathology

Classification

Phase 1

Pre-clinical PD

PD-specific pathology assumed to be present, supported by molecular or imaging markers, no clinical signs and symptoms

Phase 2

Pre-motor PD

Presence of early non-motor signs and symptoms due to extranigral PD pathology

Phase 3

Motor PD

PD pathology involves substantia nigra leading to nigrostriatal dopamine deficiency sufficient to cause classic motor manifestations followed by later non-motor features due to extension of the pathology

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

Assessment

Subjective assessment

Physiotherapy management of Parkinson’s and of older people