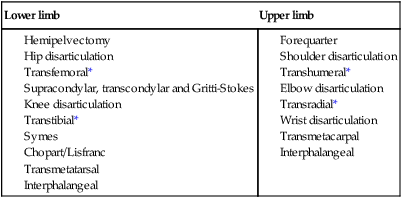

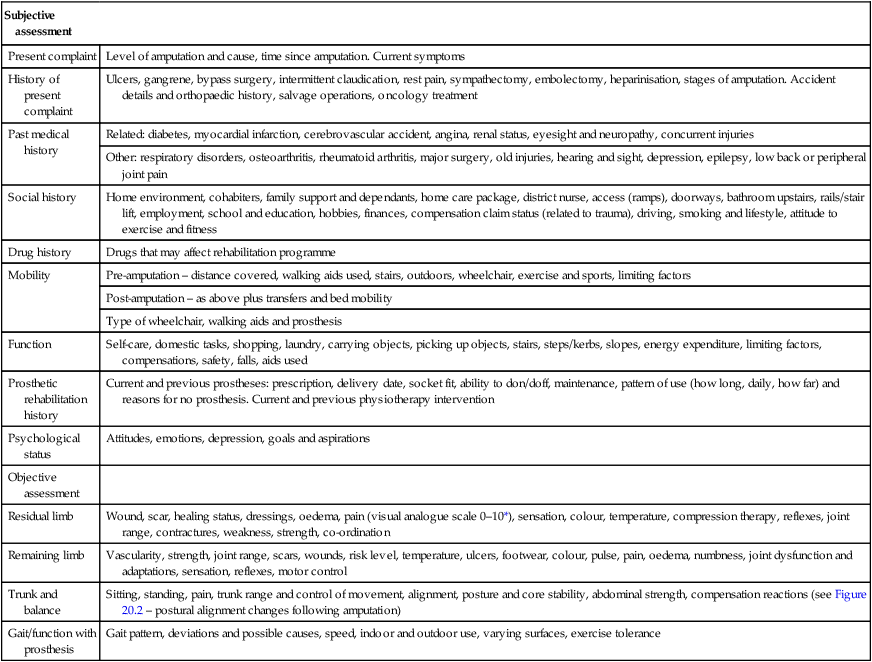

Rehabilitation following amputation is the responsibility of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT), with the patient focussed in the centre. Working with a specialist team will produce the best outcome for the individual who has undergone life-changing amputation surgery (Pernot 1997). The physiotherapist is a key member of this team, involved at all stages of the process from the pre-operative phase, through amputation and discharge home, to prosthetic training and during life thereafter. According to the Limbless Statistics (currently replacing the National Amputee Statistical Database, or NASDAB, and managed by UNIPOD), over 72% of lower limb amputations performed in the UK are as a result of vascular deficiencies, such as peripheral arterial disease and/or diabetes (Van de Ven and Engstrom 1999), whereby 50% of these people have diabetes. In fact, this is the case for the majority of lower limb amputations performed in the Western world (Ebskov 1999). Most patients in this category will be over the age of 65 years and may have other comorbidities associated with the ageing process and vascular dysfunction, such as arthritis and cardiac disease (Fyfe 1992, Ham and McCreadie 1992). As most vascular pathologies are progressive in nature, the patient may have undergone earlier intervention in the form of arterial bypass operations (to relieve blockages and narrowing in arteries) or toe amputations (as a result of tissue death) prior to a major amputation. When planning a treatment regime, these concurrent pathologies and history must be accounted for. The decision regarding amputation level is determined by the need to remove all non-viable tissue while creating a healed, pain-free, functional and potentially prosthetically suitable residuum (stump), also called residual limb. Incidentally, many patients do not like their leg being referred to as a ‘stump’ and appropriate references should be found. Where possible, when an amputation is a planned event, the physiotherapist should be involved in the amputation level decision as their assessment findings can predict postoperative functional ability and therefore the likely rehabilitation outcome. Tables 20.1 and 20.2 list the causes of amputation seen in the developed world and the recognised levels of surgical amputation. Table 20.1 Causes of amputation in the developed world (Van De Ven 1999) Table 20.2 Levels of amputation (Van de Ven 1999) *Denotes the most commonly seen levels in clinical practice. Loss of a body part and consequent change to body image can potentially lead to loss of confidence; loss of function; loss of a lifestyle; loss of role, income and status; and loss of independence and control. Having an amputation can result in people feeling vulnerable, worthless and isolated. People will be affected by each of these aspects to differing degrees and their ability to accept their new situation will also vary greatly. The normal reactions to grief and bereavement are well documented (Kubler-Ross 1969; Parkes 1972, 1975; Campling 1981); for some patients the reaction is transient and minor, while for others it is profound, disabling and longer lasting (Bradway et al. 1984; Butler et al. 1992; Krueger 1984). Anyone who has an amputation needs to be given time to adjust. They need to be given accurate information about their rehabilitation programme and realistic ideas of what they can expect. Amputation affects the whole family and loved ones should be included in any rehabilitation process (Caron 1989). A successful outcome in restoring independence and self-worth is dependent on adjustment and acceptance by the individual and their close support network. People with disability often lack choice and other people make decisions on their behalf (O’Shea and Kennelly 1996). This has the impact of denying them a role in society. The physiotherapist must take time to talk with their patient, to understand their fears and their hopes, to recognise barriers to progress and work together to set goals. Recovering after an amputation is not just about functional recovery, for example being able to ‘walk’ or to make a cup of tea. There are three potential types of pain following amputation. Amputation surgery creates tissue disruption and trauma. This produces a natural inflammatory response resulting in oedema (swelling). Refer to Chapter 12 for details. The oedema results in pressure on already injured nerve endings, causing pain. This pain is usually managed postoperatively with analgesics and possibly epidurals. Managing the oedema itself will also help with pain relief. The physiotherapist can use limb elevation, elastic compression such as Tubifast, intermittent compression and exercise to improve the circulation thereby promoting the healing process, reducing swelling and thus pain (see Figure 20.1). Normal primary healing takes around three weeks. Any delays in healing can result in greater scar tissue which can become adherent to the underlying bone and therefore be painful on skin movement, especially when under pressure. Massage and ultrasound can be helpful at relieving this type of scar pain. Phantom limb is described as sensation experienced in the missing limb part (phantom limb sensation (PLS) ) and it can, in many cases, be experienced as pain (phantom limb pain (PLP) ). It is well documented and symptoms are well recognised, if not poorly understood (Fraser et al. 2001). It is a feature that can impact significantly on the life of a patient (Hill et al 1995; Weiss and Lindell 1996; Williams and Deaton 1997). Experiencing a phantom limb can be alarming to people and they need to be reassured that this is normal, as 70% of people with amputation experience PLP (Butler and Moseley 2008). Types of phantom pain described are: ‘burning’, ‘electric’, ‘shooting’, ‘twisting’, ‘cramping’, ‘crushing’ and ‘sharp’. PLP can be intermittent or constant, and can be felt in any part of the removed limb. This can take a long time to settle down and in a few cases never resolves. It can seem worse when the individual is stressed or unwell, throughout a lifetime. It is important that the physiotherapist assesses pain carefully to determine its cause and allay patient fears that something is wrong. Effective pain relieving modalities for phantom include: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, relaxation, massage, exercise, compression and analgesia. Chapter 17 (‘Pain’) will be useful to consult. Alternative methods can include reflexology, counselling and hypnotherapy. Another significant area of pain can be the secondary pain caused by the stress to the remaining musculoskeletal system, owing to the asymmetry of the posture caused by amputation and the use of a prosthesis. It is well known that lower limb prosthetic users are prone to early onset osteoarthritis, particularly in the lower back and in the hip and knee on the remaining side (Ehde et al. 2001; Norvell et al. 2005) Your skills in the assessment and management of musculoskeletal problems will be vital. The following are reasons why some patients have difficulties achieving goals: • poor residual limb condition, e.g. adherent scar tissue, unhealed, bulbous shape, failed myodesis, neuroma, bony prominences, pain, hypersensitivity, poor vascularity, short leverage, skin frailty; • concurrent pathologies leading to an inability to learn, reduced range of motion, reduced strength and stamina, pain, poor balance, poor dexterity, socket intolerance; • social and environmental difficulties, e.g. living alone, unsuitable accommodation for wheelchairs or prostheses, poor access to accommodation, unhealthy lifestyle, dominant carers; • lack of motivation – fear, fatigue, emotional barriers to achieving success; • inappropriate equipment, e.g. poor prosthetic socket fit or alignment, a too big or too small wheelchair, incorrect prescriptions; Patients must be involved in co-ordinating all aspects of their treatment-planning, goal-setting and monitoring as self-responsibility and self-management are the foundations of rehabilitation (Watson 1996). A thorough subjective and objective assessment will ensure accurate and realistic goal planning. Table 20.3 outlines the content of both a subjective and objective assessment. It is important during the assessment that the physiotherapist gains an understanding of what the patient has been through, their current situation and their goals for the future. This needs to be in terms of their physical and psychosocial well-being. The objective assessment needs to carefully assess any musculoskeletal or neurological dysfunction and current movement control. Table 20.3 Recommended content of assessment following amputation Following amputation, the skeletal system makes compensations for the imbalance caused by the missing anatomy or the restrictions caused by the prosthesis. Joint alignment and soft tissues adapt to new prolonged postures. Muscles can start to work inefficiently and in an uncoordinated manner, affecting a person’s ability to move safely (Comerford et al. 2005). See Figure 20.2 to see the likely postural shift in someone with a lower limb amputation. The head centralises over the remaining heel and the foot has rotated outwards for increased stability. In some cases, such postural changes can result in pain. The altered biomechanics can result in increased energy expenditure and loss of confidence when moving. Restoring midline alignment aids the most efficient muscle recruitment.

Physiotherapy for people with major amputation

Introduction

Causes and levels of amputation

Developed world cause

Relative percentage (%)

Lower limb

Peripheral arterial disease (25–50% of which also have diabetes mellitus)

85–90

Trauma

9

Tumour

4

Congenital deficiency

3

Infection

1

Upper limb

Trauma

29

Disease

30

Congenital deficiency

15

Tumour

26

Lower limb

Upper limb

The psychosocial impact of amputation

Pain and pain relief

Residual limb pain

Phantom limb pain and sensations

Secondary pain

The role of the physiotherapist following lower limb amputation

Considerations

Physiotherapy assessment

Assessment

Subjective assessment

Present complaint

Level of amputation and cause, time since amputation. Current symptoms

History of present complaint

Ulcers, gangrene, bypass surgery, intermittent claudication, rest pain, sympathectomy, embolectomy, heparinisation, stages of amputation. Accident details and orthopaedic history, salvage operations, oncology treatment

Past medical history

Related: diabetes, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, angina, renal status, eyesight and neuropathy, concurrent injuries

Other: respiratory disorders, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, major surgery, old injuries, hearing and sight, depression, epilepsy, low back or peripheral joint pain

Social history

Home environment, cohabiters, family support and dependants, home care package, district nurse, access (ramps), doorways, bathroom upstairs, rails/stair lift, employment, school and education, hobbies, finances, compensation claim status (related to trauma), driving, smoking and lifestyle, attitude to exercise and fitness

Drug history

Drugs that may affect rehabilitation programme

Mobility

Pre-amputation – distance covered, walking aids used, stairs, outdoors, wheelchair, exercise and sports, limiting factors

Post-amputation – as above plus transfers and bed mobility

Type of wheelchair, walking aids and prosthesis

Function

Self-care, domestic tasks, shopping, laundry, carrying objects, picking up objects, stairs, steps/kerbs, slopes, energy expenditure, limiting factors, compensations, safety, falls, aids used

Prosthetic rehabilitation history

Current and previous prostheses: prescription, delivery date, socket fit, ability to don/doff, maintenance, pattern of use (how long, daily, how far) and reasons for no prosthesis. Current and previous physiotherapy intervention

Psychological status

Attitudes, emotions, depression, goals and aspirations

Objective assessment

Residual limb

Wound, scar, healing status, dressings, oedema, pain (visual analogue scale 0–10*), sensation, colour, temperature, compression therapy, reflexes, joint range, contractures, weakness, strength, co-ordination

Remaining limb

Vascularity, strength, joint range, scars, wounds, risk level, temperature, ulcers, footwear, colour, pulse, pain, oedema, numbness, joint dysfunction and adaptations, sensation, reflexes, motor control

Trunk and balance

Sitting, standing, pain, trunk range and control of movement, alignment, posture and core stability, abdominal strength, compensation reactions (see Figure 20.2 – postural alignment changes following amputation)

Gait/function with prosthesis

Gait pattern, deviations and possible causes, speed, indoor and outdoor use, varying surfaces, exercise tolerance

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine