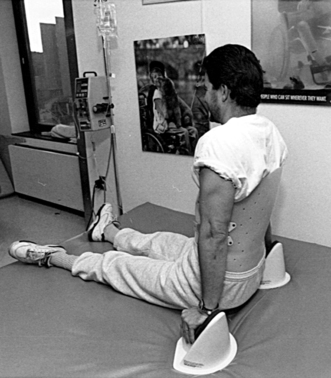

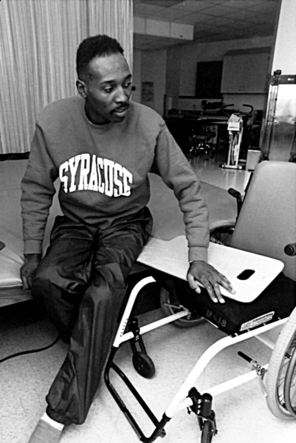

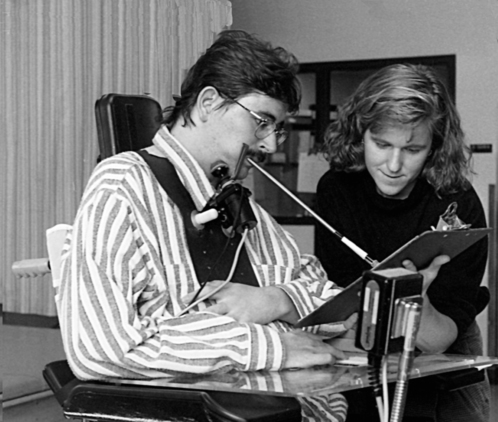

Shree Pandya and Katy Eichinger After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) computed (axial) tomography (CAT or CT) Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) nerve conduction velocity (NCV) neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT) proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stroke or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) From the description just presented, it is apparent that PTs who work with this population encounter diversity in their clients, their work settings, and the types of services they provide. This situation is a major change from the early days of physical therapy practice and even from 30 years ago, when PTs practiced under physicians’ orders only and followed prescriptions for massage, electrotherapy, thermal agents, hydrotherapy, and exercise. Today, the PT is an autonomous member of the health care team and in most states practices under direct access. As described in the patient/client management model, therapists are involved in examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, intervention, prevention, education, consultation, coordination, and other related activities (see Chapter 2). The next section provides a brief overview of some common neuromuscular disorders and the role of physical therapy in the care and management of patients with these disorders. Stroke, or cerebrovascular accident (CVA), refers to neurologic problems arising from disruption of blood flow in the brain. This disruption may be caused by hemorrhage (bleeding) or blockage from a clot that results in ischemia (decreased oxygen). The type and severity of symptoms will depend on the area of brain tissue involved. The most common symptom is a complete paralysis or partial weakness on the side opposite the site involved (hemiparesis). Depending on the site of the lesion, the paralysis may be accompanied by such symptoms as difficulty speaking or understanding the spoken word, visual problems, and neglect of the affected side. Approximately 22% of men and 25% of women die within 1 year of having the stroke. Of the survivors, approximately 30% to 40% have severe disability.1 A major psychological problem after stroke is depression, which can have a great impact on management. Recovery from stroke occurs most rapidly during the first 6 months, but functional gains can be seen for 2 years or longer. Currently under investigation are several medications that have thrombolytic properties, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA); medications that have neuroprotective properties, such as glutamate antagonists; and calcium channel blockers, which have the ability to halt or reverse the cascade of events after ischemia. Some (such as tPA) are effective only if given within the first 3 to 6 hours after the stroke. Hence a key issue is to educate the public regarding the symptoms of a stroke and have them seek immediate attention for this “brain attack,” just as they would for a “heart attack.” Figures 9-1 and 9-2 illustrate the preventive and functional training aspects of management of a patient with left-sided paralysis secondary to stroke. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is most often caused by motor vehicle accidents or by falls and violence.2 Because of the nature of the injury, the brain trauma may be associated with fractures, dislocations, lacerations, and the like. The groups most commonly affected are children (from bicycle accidents) and young adults (from car accidents and violence); TBI is the most common cause of death and disability in these age groups. Early management is focused on preservation of life and prevention of further damage. The diffuse nature of the brain injury usually results in problems with multiple brain functions and mechanisms. A complex picture is common, with varying deficits in motor and sensory capabilities, intellectual and cognitive functions, and emotional and psychological functions. Because of the complexity and variability of problems that may be encountered with each patient, management and treatment require an individualized plan and a multidisciplinary team approach in which each member plays a specific and significant role. Early physical therapy involvement has been shown to be beneficial. As with stroke, physical therapy intervention focuses on facilitating functional recovery. TBI is an area in which prevention through education is crucial. Wearing a helmet when riding a bike and using a seat belt when riding in a car can make the difference between life and death. Spinal cord injury (SCI), like TBI, most often results from motor vehicle accidents, falls, violence (especially gunshot wounds), and sports (diving and football). The age group most often affected is 16 to 30 years of age, and men are affected four times as often as women.3 Spinal cord damage can also be precipitated by other diseases and conditions, and in these instances older patients are affected more commonly. Depending on the level of injury, all limbs may be affected (tetraplegia), or the lower part of the trunk and legs may be affected (paraplegia). If the lesion is complete, no residual sensory or motor function can be found below the level of the lesion (“-plegia”). The injury may also result in an incomplete lesion in which some distal motor and sensory functions may be preserved (“-paresis”). While this healing process occurs, it is important to maintain mobility in the joints of the extremities, strength in the unaffected muscles, cardiorespiratory capacity, and endurance. Figure 9-3 illustrates one of the types of braces used to provide stability. The patient is working on strengthening the upper extremity and trunk muscles. Once medical and orthopedic clearance is obtained, more vigorous functional training is begun. In Figures 9-4 and 9-5 the patients are learning mat table–to-wheelchair transfers and wheelchair manipulation skills. Identification of equipment requirements and environmental adaptations is needed for each patient. For example, most patients use a wheelchair as a primary means of mobility, and they must be custom ordered for each patient with specific size and adaptation requirements. Figure 9-6 shows a patient with tetraplegia using an electric wheelchair for mobility and a special device that allows him to write. The home will have to be made wheelchair accessible with ramps and other modifications. Thus the therapist plays a major role not only in the treatment, but also in the rehabilitation of patients with SCI by providing family education and consultation on many related issues such as environmental modifications and assistive technology The vestibular system helps detect head position and movement. It consists of two components: (1) the peripheral apparatus, which includes the semicircular canals in the inner ear, and the central component, which includes the vestibular nuclei, and (2) the connections between the peripheral and central components, which include the vestibular nerve, and the central connections between the vestibular nuclei and various brain regions. The vestibular system, in conjunction with other systems, allows us to maintain our orientation in space, control our posture, and maintain our balance. The most common symptoms of vestibular disorders are dizziness, unsteadiness, vertigo, and nausea. According to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey for 1991,4 dizziness or vertigo is among the 25 most common reasons Americans visit their doctors. U.S. physicians report a total of more than 5 million dizziness or vertigo visits a year. Vestibular disorders can occur as a result of trauma, infections, toxicity from large doses of antibiotics, and pathologic changes underlying other conditions such as MS and stroke. Common vestibular diagnoses include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, labyrinthitis, vestibular neuritis, and Meniere’s disease.

Physical Therapy for Neuromuscular Conditions

Discuss the role of the physical therapist in the management of patients with neuromuscular disorders

Discuss the role of the physical therapist in the management of patients with neuromuscular disorders

Describe some of the common neuromuscular conditions in which physical therapists play an essential role

Describe some of the common neuromuscular conditions in which physical therapists play an essential role

Compare the different roles a therapist may play, depending on the patient’s condition and problems

Compare the different roles a therapist may play, depending on the patient’s condition and problems

General Description

Common Conditions

Stroke

Traumatic Brain Injury

Spinal Cord Injury

Vestibular Disorders

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine