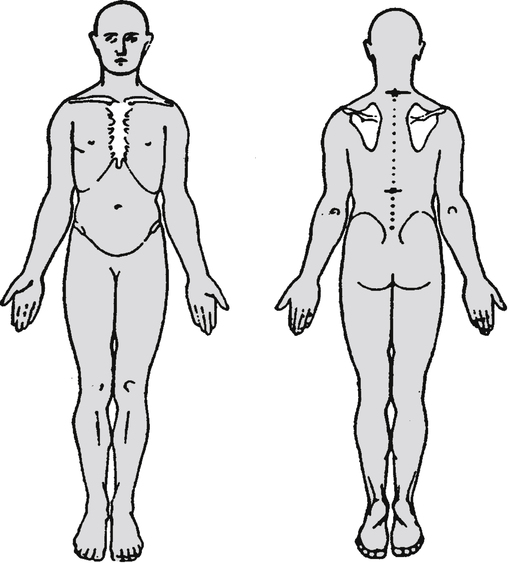

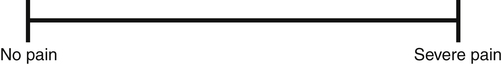

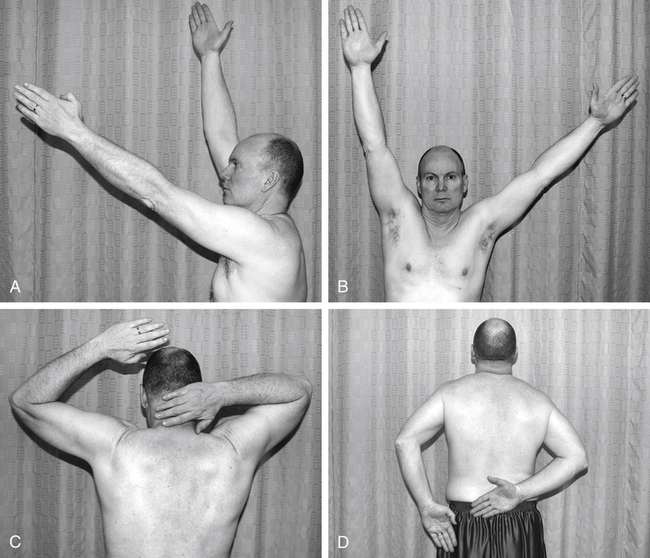

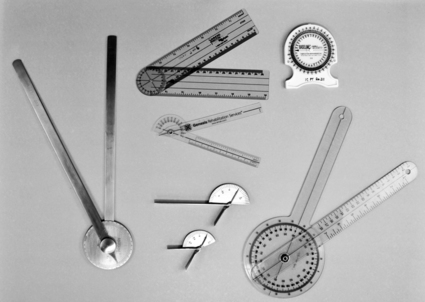

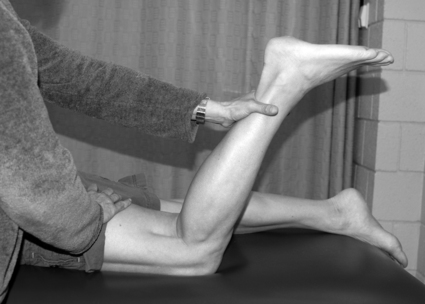

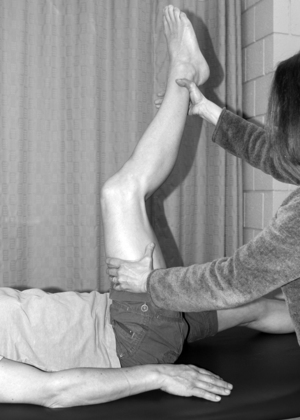

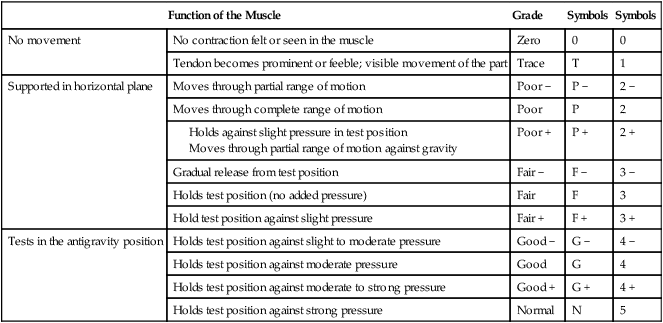

Barbara C. Belyea and Hilary B. Greenberger After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: Although the clinical interests or approaches to patient care may be diverse, the common thread throughout physical therapy for musculoskeletal conditions is the focus on a patient’s function. By examining the patient’s functional abilities, the PT determines the cause and extent of any limitations and restrictions in desired activities, and works with the patient/client to return the individual to his or her preinjury level of function in the shortest time possible.1 A person’s function can be affected when a disruption occurs in the musculoskeletal system. This disruption may be the result of traumatic or repeated stress to tissue, structural imbalances of muscle or bone, congenital conditions, surgery, or degenerative changes in the body. Dysfunctions of the musculoskeletal system often result in symptoms of pain, stiffness, edema (swelling), muscle weakness or fatigue, or loss of range of motion (ROM; movement at a joint). The history involves gathering information about the current and past health status of the patient related to why the patient/client is seeking the services of a PT.2 The information may be obtained by interviewing the patient or the patient’s family, by accessing the patient’s medical record, and by consulting with other members of the patient’s health care team. The history is qualitative information based on the patient’s perception of the problem and is therefore included in the “S” portion of the “SOAP” note (see Chapter 2). The role of the therapist during the interview is to guide the patient through pertinent questions about the patient’s musculoskeletal condition. This interaction allows the therapist to develop a rapport with the patient and to understand the patient’s insight into and opinion of the problem. The interview also assists the therapist in appropriately directing the remainder of the examination. Often, the patient interview will give the therapist ample information to make a preliminary physical therapy diagnosis. Questions asked during the interview include information about the onset of the condition, current symptoms, previous physical therapy treatments, past medical history, and lifestyle and health habits pertaining to work and recreation. Box 8-1 lists typical questions asked during the patient interview. In addition to these questions specific to the patient’s reason for seeking physical therapy, the therapist should perform a review of symptoms (ROS) in order to identify symptoms that may have been overlooked in the history and to screen for medical conditions that may require referral to other health care providers.3 The ROS is usually performed by using checklists of common symptoms typically associated with various systems of the body (e.g., cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal system). For more specific information about the location of symptoms, the patient is often asked to draw the location of the symptoms on a body chart (Figure 8-1). Pain scales may also be used to gauge the amount of pain the patient is experiencing (Figure 8-2). On completion of the history taking, the therapist should have gained information regarding the description and location of symptoms, nature of the disorder (acute versus chronic condition), behavior of the symptoms (what activities make the symptoms either better or worse), health risk factors that may be present, and limitations in activities the patient may be experiencing. The objective portion of the examination refers to quantitative or qualitative measurements that are taken by the PT. This portion of the examination begins with a systems review and is included in the “O” section of the SOAP note (see Chapter 2). The systems review includes a brief examination of the other systems of the body related to physical therapy (e.g., cardiovascular, neuromuscular, integumentary) and information about the patient’s cognition, communication, and preferred learning style.2 The information gathered during the systems review assists the therapist in developing an appropriate, individualized plan of care and may further identify health problems that may require consultation with or referral to another health care provider. In a patient with a musculoskeletal condition, common systems reviews may include monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure, assessment of skin integrity, and a gross assessment of joint ROM, strength, and coordinated movements. Active range of motion (AROM) refers to the ability of the patient to voluntarily move a limb through an arc of movement. AROM provides the therapist with information regarding the quality of the movement (smooth versus rigid movement), the willingness of the patient to move the limb, any pain produced during movement, and whether the patient has any limitations in the motion as compared with the unaffected side. An example of AROM of the shoulder in multiple planes is provided in Figure 8-3. Many methods may be used to measure and document AROM and PROM. The most common measurement technique, goniometry, is performed with a goniometer and measures joint angles. Examples of goniometers are shown in Figure 8-4. The amount of motion available at any joint depends on the structure of the joint. In addition, norm values for joint ROM depend on several factors, including the patient’s age and gender.2 Typically the therapist compares ROM values of the affected joint with those on the unaffected side. Figure 8-5 shows a PT conducting a PROM measurement of a patient’s knee flexion. Strength can be defined as the amount of force produced during a voluntary muscular contraction. This contraction may be performed statically (no motion) or dynamically (through an assessment of ROM). When one is assessing the status of the muscles and tendons, a quick resisted test is used. This test allows the therapist to determine the general strength of a muscle group and assess whether the muscle contraction produces pain. If the resisted test shows that a muscle or muscle group is weak or painful, further testing may be performed to isolate the specific muscle. To isolate and test specific muscles, manual muscle testing (MMT) is performed (Figure 8-6). MMT allows the therapist to assign a specific grade to a muscle. This grade is based on whether the patient can hold the limb against gravity, how much manual resistance can be tolerated, and whether the joint has full ROM. Several systems of grading are widely used. One of the most common grading systems was initially described by Robert Lovett, MD, and later modified by Henry Kendall, PT, and Florence Kendall, PT.4 This key to muscle grading is outlined in Table 8-1. Table 8-1 Key to Manual Muscle Testing Grades Modified from Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, et al: Muscles: testing and function, ed 5, Baltimore, 2005, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Appropriate flexibility or balance of muscles is a key component of proper posture and body mechanics. Many musculoskeletal problems seen in the physical therapy clinic can be linked to muscle imbalances that have caused movement dysfunctions.5 For example, if the muscles surrounding the shoulder did not act synergistically (because of lack of flexibility), compensation might occur at joints distal and proximal to the shoulder, such as the elbow and cervical spine. A PT may perform a number of tests to determine flexibility. One common test for the lower extremity is the 90/90 straight leg raise (Figure 8-7). This test objectively measures flexibility of the hamstring muscles, located on the posterior aspect of the thigh. Traditionally, functional assessment has referred to such activities as the patient’s bed mobility, transfers between a variety of surfaces (e.g., moving from a sitting position in a wheelchair to a standing position), and ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), such as hair combing, dressing, and bathing. PTs may spend a large percentage of their time during the initial examination assessing the patient’s ability to perform these ADLs. Box 8-2 lists examples of ADLs.

Physical Therapy for Musculoskeletal Conditions

List common conditions seen in musculoskeletal physical therapy

List common conditions seen in musculoskeletal physical therapy

Identify the components of an initial musculoskeletal examination

Identify the components of an initial musculoskeletal examination

Define and give examples of the various tests and measures used in physical therapy for musculoskeletal conditions

Define and give examples of the various tests and measures used in physical therapy for musculoskeletal conditions

List the general goals of a therapeutic exercise program

List the general goals of a therapeutic exercise program

Describe the various types of therapeutic exercises

Describe the various types of therapeutic exercises

Describe various physical agents used to address musculoskeletal problems

Describe various physical agents used to address musculoskeletal problems

General Description

Principles of Examination

Patient History

Systems Review

Tests and Measures

Active Range of Motion

Passive Range of Motion

Strength

Function of the Muscle

Grade

Symbols

Symbols

No movement

No contraction felt or seen in the muscle

Zero

0

0

Tendon becomes prominent or feeble; visible movement of the part

Trace

T

1

Supported in horizontal plane

Moves through partial range of motion

Poor −

P −

2 −

Moves through complete range of motion

Poor

P

2

Poor +

P +

2 +

Gradual release from test position

Fair −

F −

3 −

Holds test position (no added pressure)

Fair

F

3

Hold test position against slight pressure

Fair +

F +

3 +

Tests in the antigravity position

Holds test position against slight to moderate pressure

Good −

G −

4 −

Holds test position against moderate pressure

Good

G

4

Holds test position against moderate to strong pressure

Good +

G +

4 +

Holds test position against strong pressure

Normal

N

5

Flexibility

Functional Tests