CHAPTER 4 Physical Examination of the Elbow

HISTORY

Functionally, the elbow is the most important joint of the upper extremity, because it places the hand in space away from or toward the body. It provides the linkage, allowing the hand to be brought to the torso, head, or mouth. Because of this, the examiner must be aware of the interplay of shoulder and wrist function as they complement the usefulness of the elbow. However, a considerable limitation of elevation and abduction function can exist at the shoulder complex without producing an appreciable compromise in most activities of daily living. This is true because only a relatively small amount of shoulder flexion and rotation is necessary to place the hand about the head or posteriorly about the waist or hip, and scapulothoracic motion can compensate for glenohumeral motion loss. Full pronation and supination can be achieved only when both the proximal and distal radioulnar joints are normal.6,25

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

AXIAL ALIGNMENT

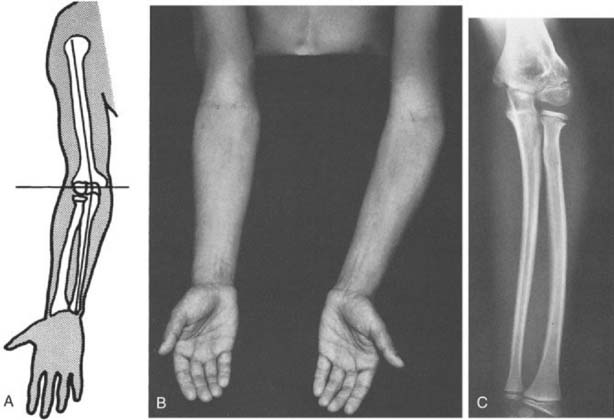

Axial malalignment of the elbow, when compared with the opposite side, suggests prior trauma or a skeletal growth disturbance. To determine the carrying angle, the forearm and hand should be supinated and the elbow extended; the angle formed by the humerus and forearm is then determined (Fig. 4-1A). Although there is considerable variation with race, age, sex, and body weight, an average of 10 degrees for men and 13 degrees for women has been calculated as the mean carrying angle from several reports.3,4,13,14

Angular deformities, such as cubitus varus or valgus, are also easily identifiable (see Fig. 4-1B and C). The elbow moves from a valgus to varus alignment as with flexion. In a post-traumatic condition, however, abnormalities in the carrying angle cannot be accurately assessed in the presence of a significant flexion contracture (see Chapter 3). Rotational deformities following supracondylar or other fractures of the humeral shaft may be difficult to perceive.

LATERAL ASPECT

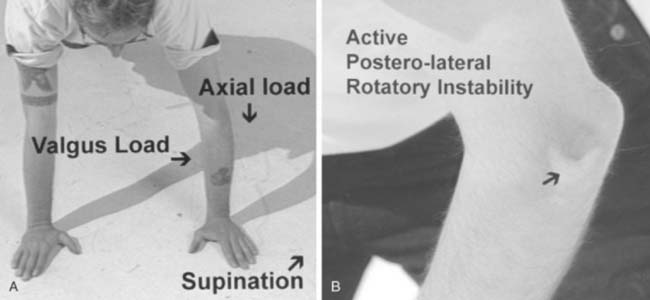

Fullness about the infracondylar recess just inferior to the lateral condyle of the humerus, the “soft spot,” suggests either an increase in synovial fluid, synovial tissue proliferation, or radial head pathology, such as fracture, subluxation, or dislocation (Fig. 4-2). Subtle evidence of effusion can be determined by observing fullness in this area.

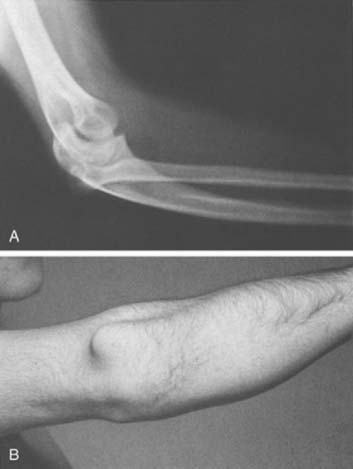

Thin, taut, adherent skin over the lateral epicondyle may be indicative of excessive cortisone injections in this area for refractory lateral epicondylitis (see Chapter 44). A prominence involving the lateral triangle often indicates a posteriorly dislocated radial head (Fig. 4-3; see Fig. 4-22A and B).

POSTERIOR ASPECT

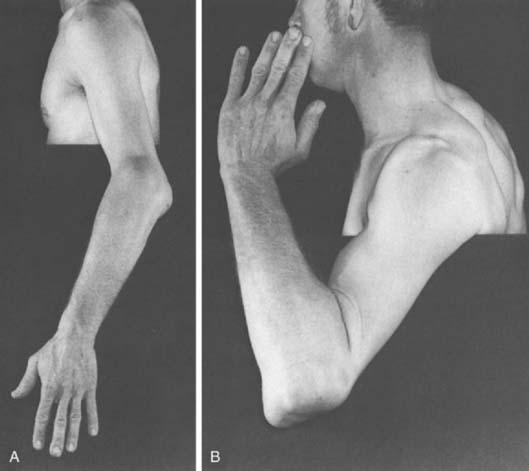

A prominent olecranon suggests a posterior subluxation or migration of the forearm on the ulnohumeral articulation. Occasionally, marked distortion is associated with surprisingly satisfactory function (Fig. 4-4). Rupture of the triceps tendon at its insertion should be suspected if this finding is accompanied by loss of active extension. Loss of terminal passive extension of the elbow is a sensitive but nonspecific indicator of intra-articular pathology. Loss of active motion with full passive extension suggests either mechanical (triceps avulsion) or neurologic conditions.

The prominent subcutaneous olecranon bursa is readily observed posteriorly when it is inflamed or distended (Fig. 4-5). Rheumatoid nodules frequently are found on the subcutaneous border of the ulna (see Chapter 74).

MEDIAL ASPECT

On occasion the ulnar nerve may be observed to displace anteriorly during flexion with recurrent subluxation of the ulnar nerve.8 Otherwise, few landmarks are observable from the medial aspect of the joint. The prominent medial epicondyle is evident unless the patient is obese.

ASSOCIATED JOINTS AND NEURAL FUNCTION

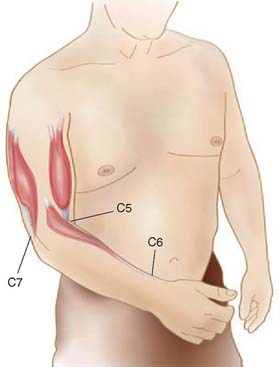

No examination of the elbow is complete without a review of the cervical spine and all other components of the upper extremity. If the elbow pain has a radicular pattern, it is important to review the patient’s cervical spine alignment and range of motion and perform neurologic testing of the entire upper extremity. The main nerve roots involved with elbow function are C5-7 (Fig. 4-6). There is considerable overlap in the sensory dermatomes of the upper extremity. The general distribution of sensory levels includes C5, the lateral arm; C6, the lateral forearm; C7, the middle finger; and C8 and T1, the medial forearm and arm dermatomes, respectively.

Biceps function from innervation of C5-C6 is a flexor of the elbow and forearm supinator. The reflex primarily tests C5 and some C6 competency. The C6 muscle group of most interest is the mobile wad of three, consisting of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis and the brachioradialis muscles. These also are known as the radial wrist extensors and should be assessed for strength and reflex integrity. The reflex is primarily a C6 function, with some C5 component. The primary elbow muscle innervated by C7 is the triceps, which should always be assessed for strength and reflex. Wrist flexion and finger extension also are primarily supplied by C7, with some C8 innervation (see Fig. 4-6).

For normal forearm rotation, there must be a normal anatomic relationship between the proximal and distal radioulnar joint. Inflammatory changes involving either the elbow or the wrist or both will cause a loss of forearm rotation. Disruption of the normal relationship of the distal radioulnar joint will cause dorsal prominence of the distal ulna exaggerated by pronation and is lessened by supination. Because pronation is the common resting position of the hand, dorsal subluxation of the ulna at the wrist is often identifiable by inspection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree